She lived through the entire 20th century – the Russian Revolution, both world wars, the birth of Nazism, independence movements, and even the fall of a messiah. She was an immigrant, an actress, she danced in cabarets and acted in Bollywood, even gaining recognition in Hollywood. But above all, she brought yoga to the Western world.

It is hard to say who was the most prominent disciple of Indra Devi. Some say it was Greta Garbo who made her famous, others maintain that it was Gloria Swanson, who was photographed in Devi’s yoga studio just after the premiere of Sunset Boulevard, when everyone in the US was raving about her. Marilyn Monroe is also known to have practised yoga and there was even a photo of her allegedly practising with Devi – though it was actually revealed to be another Hollywood blonde, Eva Gabor. Nevertheless, it was commonly believed that Monroe was also a student of the first Hollywood yogi, a rumour that certainly did Indra no harm.

When she arrived in youth-obsessed Los Angeles at the end of 1947, she was approaching 50 years old. She knew no one in her new country, and her old country no longer existed.

First enchantment

She was born Eugenie Peterson in 1899 in Riga, an important port of the Russian Empire at the time. Her father was Vasili Pavlovich Peterson, a banker of Swedish descent who would provide an affluent life for his upper-class, 16-year-old wife, Sasha Zitovich. Or so the father of the bride, a high-ranking official of the tsarist police, envisioned when he accepted the banker’s courtship of his daughter. However, the marriage fell apart before the first birthday of their daughter Eugenia, known as Zhenya. Peterson disappeared from their lives and Sasha returned to her father’s house with the child.

The young mother, still a teenager, decided to become an actress, despite her father’s categorical objection. Riga was a cosmopolitan city at the turn of the 20th century, but in aristocratic circles, acting was still treated almost on a par with prostitution. However, Sasha soon got her own way. From then on, to the despair of young Zhenya, she would disappear, sometimes for years at a time, before reappearing again, to her daughter’s delight. On the one hand, Zhenya admired her mother for going against conventions, while on the other hand, she was accompanied by constant anxiety due to Sasha’s absences.

At the beginning of 1914, Zhenya was visiting Sasha in Moscow when she came across the word ‘yoga’ for the first time. While visiting the home of actors from the Moscow theatre, 15-year-old Zhenya sneaked out of the room and into the library. There she found a book open on the desk: Yogi Philosophy and Oriental Occultism. The author was Yogi Ramacharaka, the pseudonym of William Walker Atkinson, a lawyer from Chicago; while he had never been to India, he had experienced a spiritual rebirth following bankruptcy and a nervous breakdown.

The teenager began to read: “The care of the body, under the intelligent control of the mind, is an important branch of yogi philosophy, and is known as ‘Hatha Yoga.’” At that moment, their host appeared in the library, took the book from her hands and began to read out loud. The girl wrote in her diary that when she heard the text, she felt her cheeks burning. She said: “I must go to India,” to which the man replied, closing the book: “You are too emotional, my dear.”

Escape to adventure and liberation

The dream of going to India took root in Zhenya’s mind. At the beginning of the 20th century, Russia was open to occultism, spiritualism, Eastern philosophy, Kabbalah and esoteric magic. Initially, however, the teenage Zhenya decided to follow in her mother’s footsteps and enrolled at an acting school. A few years later, before she had even graduated, she got her first job in a Moscow theatre. She was no longer restricted by the corsets of the aristocracy – after all, there was a war going on, revolution had just broken out in Russia.

After their defeat, the ‘white’ Russians faithful to the tsar emigrated en masse to various places, including Berlin. In 1922, Sasha and Zhenya took this very path. They both found employment in the Russian theatres and cabarets operating in the capital of the Weimar Republic.

Still, Zhenya, now in her 20s, felt the need for spirituality. When she saw an advertisement in 1926 for the Star Camp organized in Ommen, the Netherlands, her heart soared. The most important speaker at the event, run by the Order of the Star in the East, was Jiddu Krishnamurti himself – the incarnation of the messiah who was being groomed by the Theosophical Society for the role of World Teacher. Zhenya felt that this trip would set her on the right track. As she approached 30, she was increasingly aware of the fact that she was relinquishing a life full of adventure for the sake of peace, quiet and bourgeois comforts. But she was still drawn to exploration.

She had never slept in a tent before and was not even accustomed to washing dishes. She found the vegetarian meals served at the camp bland, but at the same time she was enchanted and delighted by everything around her.

Nor had she ever meditated before, but her first time was something she never forgot. Despite there being over a thousand people in the tent, it was silent. She closed her eyes and tried to concentrate. Perched on a small dais, Krishnamurti began chanting a Sanskrit mantra. Later, she recalled feeling strange. She was convinced that she knew the text, although she also knew that she had never heard it before. Choked with emotion, she began to shake. She wrote afterwards that it was a kind of ‘inner shock’. When she opened her eyes, she realized that the meditation had finished. She ran from the tent and burst out crying; after wiping away her tears, she felt happy, at ease and liberated.

Seeking destiny

When Zhenya returned from the camp, she knew what she had to do. In Riga, where she moved in the summer of 1927 after her mother got a job in her hometown, she met Alice Adair. The British feminist and aesthete had just completed a series of meetings in Europe and was returning to India, where she lived at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society. It was there that the annual conference was to be held in December, and Krishnamurti was again expected to appear. After the two women made friends, Alice became Zhenya’s first spiritual guide and invited her to India.

A few months later, Zhenya boarded a steamboat sailing to Australia via Ceylon (today Sri Lanka). After almost a month, she reached Colombo, where she boarded another ship to Madras (today Chennai). At last, she had reached her own promised land, and she was captivated by it. She soon started wearing a sari, converted to ‘bland’ vegetarianism, and delighted in the colours that surrounded her. She felt at home.

After four months she had to return to Europe, but she found that nothing – not even her acting career and growing popularity – brought her pleasure anymore. She spoke only of India, and felt her longing for this country and its spirituality almost physically. Her upcoming marriage to a German banker from Latvia, Hermann Bolm, whose proposal she had accepted sometime earlier, seemed like a trap, so she gathered her courage and broke off the engagement. She was 30 years old, which by the standards of the time made her a ‘pitiful old maid’, but she felt that she had made the right decision.

That summer, she returned to Ommen for what would turn out to be the last camp of the Order of the Star in the East. On 3rd August 1929, during a speech to over 3000 people gathered in a field, Krishnamurti, who had long been planning to leave the order, officially denounced Theosophy. Although most of his followers felt betrayed and abandoned, Zhenya admired Krishnamurti’s courage and uncompromising attitude. According to her biographer Michelle Goldberg, they both felt the need to break with the past and start afresh.

Zhenya followed her heart: in November 1929 she sold the remains of her family’s jewellery and the things that had survived the turmoil of war, revolution and constant relocations, said goodbye to her mother, and set off on another journey.

New roles

Having no plan, she started from what she knew well: the Theosophists’ December convention in Adyar. Krishnamurti also made an appearance, but the atmosphere was tense and unpleasant. In February 1930, the former World Teacher left Bombay (now Mumbai) for California.

Zhenya herself was already known to the theosophists as an actress and dancer. During a dance recital organized for her in Bombay, she was noticed by Bhagwati Prasad Mishra – one of the most important directors of early (still silent at that time) Bollywood cinema. It was he who suggested she could start appearing in front of the camera under the pseudonym Indira Devi; in Sanskrit, devi means goddess.

In the silent film Arabian Knight, she played the protagonist’s mistress and ‘the most beautiful girl in Baghdad’. Although she had serious doubts as to whether she was cut out for the role, Mishra convinced her. She was also persuaded to go on a date with 34-year-old Jan Strakaty, an economic attaché to the Czechoslovakian Embassy. Although diplomats tended not to be concerned with spiritualism, theosophy or yoga, Jan and Zhenya did share some common views: like her, he supported Indian independence and the emancipation of women. Zhenya-Indira Devi felt that she had a lot in common with Jan, and at the same time she believed strongly that their relationship would not limit either person’s independence. She also understood that Strakaty was looking for a companion for endless diplomatic receptions, dinners and banquets, but someone that had more about them than good looks. Meanwhile, she wanted financial stability. So when Jan proposed, she agreed without hesitation, and thus became a fiancée for the second time in her life – and soon, for the first but not the last time, a wife.

The Maharaja’s hatha yoga

Marital stability didn’t last long. At the beginning of 1936, the Czechoslovakian government decided to turn Zhenya’s life upside down by transferring Jan to Shanghai. He left right away, she stayed to oversee the move. Before she joined him, however, she learned of a hatha yoga school – perhaps the most important of its time – operating in the beautiful palace of the Maharaja of Mysore under the patronage of the ruler. It was led by Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who claimed to have developed and perfected 3000 asanas. He also claimed that he could control his body to the extent that he was able to stop his own heartbeat.

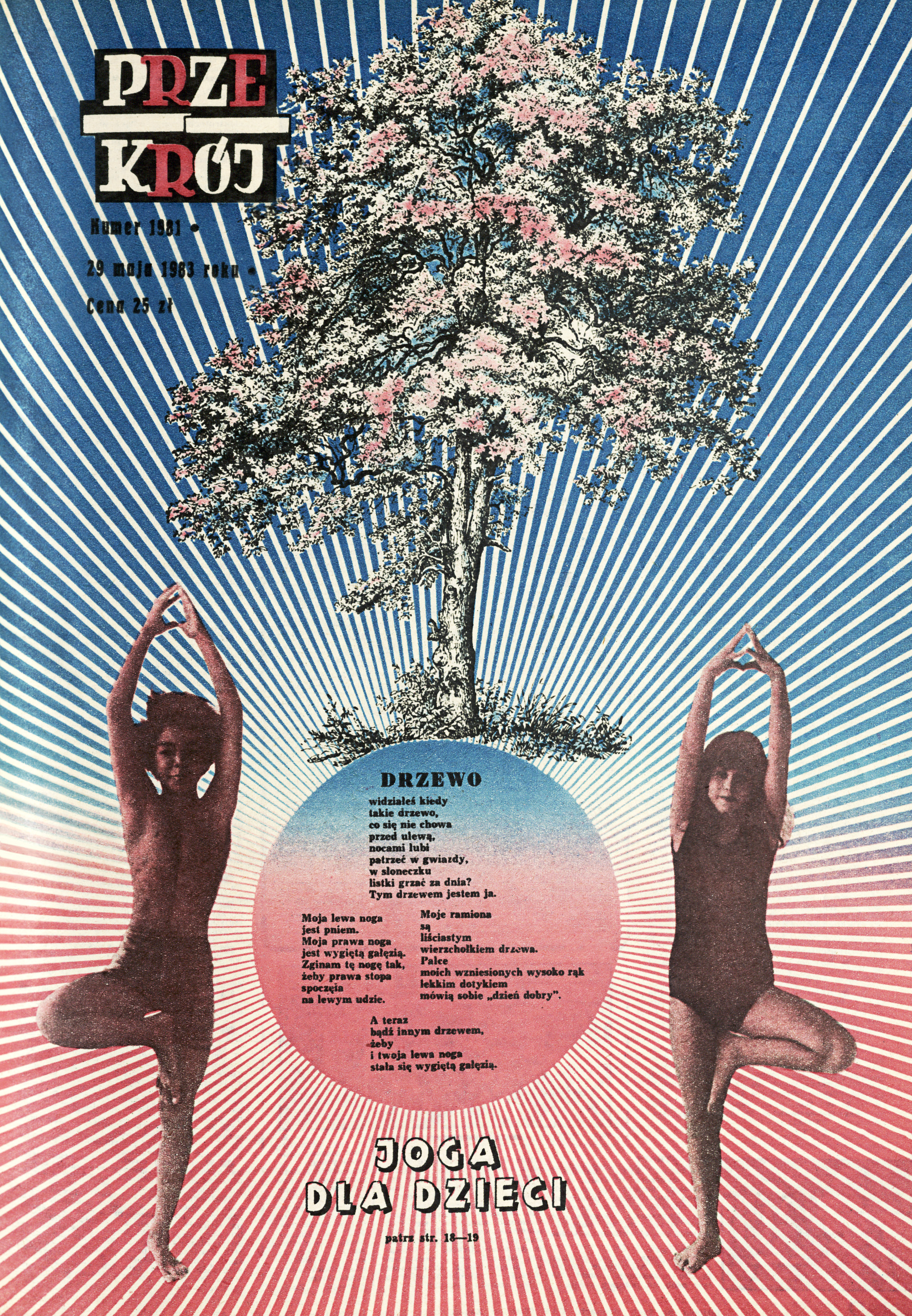

At the beginning of the 1930s, yoga as a form of physical exercise was not prevalent even in India; it was a system of Hindu philosophy which said that through meditation and following ethical principles, a yogi could achieve liberation from the cycle of incarnations (sansara). As yogis spent long hours immobile while meditating, they developed hatha yoga, which involved stretching exercises or asanas. The extent to which this branch was developed in ancient times is a subject of debate. Yoga researcher Mark Singleton argues that hatha yoga is largely a creation of the 20th century, and points out that the descriptive names of the asanas in Sanskrit were actually given in the 1920s and 30s. He highlights the similarities between yoga exercises and the system created by the Danish physical education teacher Niels Bukh, which was used by the British army stationed in India. According to Singleton, it was in the palace of the Maharaja of Mysore that the syncretic system of exercises known to us today, combining modern and ancient practices, was created.

Many years later, Zhenya – as Indra Devi (after a few years, by the time she was a hatha yoga teacher, she abbreviated her pseudonym) – would teach Americans that hatha yoga was deeply rooted in ancient practices. But before she left for America and opened her school, it was actually a miracle that she learned anything from her guru at all. Although he met with her and answered her questions quite willingly, he absolutely refused to train her – in fact, he didn’t teach foreigners at all, let alone women. In order for Krishnamacharya to take Indra under his wing, the Maharaja himself had to intervene.

The teacher hoped that his new student would soon become discouraged. He began by imposing on her an extremely strict regime. He had no idea, as her biographer writes, that this discipline was exactly what Indra, the world-weary diplomat’s wife, craved.

Rise before sunrise, then asanas, meditation and learning new poses. Dinner two hours before sunset. She was to be in bed by 9.30pm, which meant she couldn’t participate in the social events held at the palace. The next stage of training was pranayama – breathing exercises. This came surprisingly easily to her, as she mentioned to her master. In response, she was told that “although pranayama may seem simple, it is extremely powerful and, used wrongly, can be disastrous, leading to serious physical and mental troubles.”

The training lasted eight months, until December 1936, when Indra planned to join her Czechoslovakian husband in Shanghai. However, the day before the schooling ended, Krishnamacharya summoned Indra and announced that he had plans for her. “Now that you are going to visit other countries in the world, I want you to teach yoga,” he told her. At first she protested, saying that she couldn’t convey what she had only just learned herself. But the guru was impossible to refuse. She embarked on the journey to her husband as a fully-fledged hatha yoga teacher.

Wandering teacher

Shanghai was a multicultural city. Two years after Indra’s arrival, when World War II broke out in Europe, refugees began to flock there in large numbers. A dozen or so years earlier, the ‘white’ Russians had arrived there after fleeing the Revolution. They were the second largest minority after the Japanese, numbering in the tens of thousands. There was also a Theosophical Society – there was still an interest in the occult among Russian immigrants, but yoga remained unknown. The first person to respond to Indra’s advertisement when she opened a yoga school in 1939 wanted to know if she could communicate with spirits. A month after renting a venue, she still had no students. Eventually, someone suggested she organize a yoga demonstration for the diplomatic elite. This was what enabled her to tell people what yoga actually was. Many people attended, mainly from the American Embassy, including the consul’s wife. And they were certainly surprised.

Indra began her lessons with breathing exercises, followed by neck and eye exercises and ‘sound vibrations’ – a syllable maintained on an exhale for as long as possible. Before the asanas came a phase of deep relaxation – shavasana, which nowadays constitutes a fixed point of the programme at the end of yoga classes around the world. After 20 minutes, the asanas began. Indra Devi presented yoga as a way of attaining eternal youth, health and vitality. In fact, she turned out to be the best advertisement for her practices – she died in 2002 at the age of 103.

Indra spent seven years in Shanghai, during which time she brought her mother over to join her. Although she had a German passport and citizenship – a legacy of the times when Latvia was occupied by the Germans during World War I – in September 1945 she disposed of these documents and obtained Czechoslovakian papers. She did this not out of love for her husband – her marriage to Strakaty was practically over. As soon as she was allowed to travel freely after the war, Indra boarded a ship for Bombay, while Jan sailed to Europe on a British repatriation ship. She never saw him again.

Yoga in the City of Angels

Keen to spend the rest of her life in India, Indra became a student of another famous hatha yoga guru, swami Sivananda, who was said to have reached the state of transcendence – the highest level of initiation and the goal of every yogi. However, after a few months, she returned to Shanghai. There was a civil war going on in China between the nationalists and the communists, and the general of the army had demanded the house where Indra’s mother had been living. When Indra arrived to resolve the problem, Sasha begged her not to return to India. She was worried about her daughter – there was much talk at the time of violence in the subcontinent and the Muslims’ aspirations to create their own state. She urged Indra to go with her to America, to sunny California. She had heard from a friend, Sonia, that a yoga school was opening in Hollywood where Zhenya (to her mother, Indra was always Zhenya) would be sure to find work.

Indra was torn. She later revealed that she had booked two tickets in Shanghai: one to India and the other to the US. She planned to take a chance and board the first ship that called at the port. Her biographer, however, is convinced that this story was invented for the media. If India was Devi’s spiritual homeland, what did Hollywood have to offer her? It was easier to say it had happened by chance. In fact, she had applied for a US visa well in advance.

However, there was no yoga school job awaiting her in Los Angeles, because no such place had ever existed in Hollywood. As luck would have it, Indra had friends in common with Bernardine Fritz, who ran a well-known Hollywood social club. Fritz hosted a welcome party in her honour and, as Michelle Goldberg describes, the guests were enchanted by the woman in the saffron sari, speaking English with a strong East European accent and introducing herself by an Indian name. Devi once again found her place among the key players in society.

At the urging of her new friends, she rented a property on Sunset Boulevard, a few blocks from the iconic nightclubs Mocambo and Ciro’s, and opened Los Angeles’ first yoga school herself. Apparently, the sessions were not terribly comprehensive – Devi talked a lot about the health benefits, but when it came to the spiritual level, she advised turning to the real gurus (it is likely that her teaching style was similar to the approach of many Western yoga schools today).

A roaring success

Devi’s second husband was Siegrid Knauer, an unconventional homeopath who was well-known in Hollywood circles. He had travelled a very similar path to Zhenya – both spiritually, and in terms of distance. Born in Kyiv to a German family, he was a student of Rudolf Steiner, a theosophist who, having proclaimed Krishnamurti the World Teacher, abandoned the movement and founded his own Anthroposophical Society. After emigrating to the US, before World War II, Knauer settled in Los Angeles and became famous as a doctor of Hollywood celebrities. Knauer’s marriage to 54-year-old Devi made them one of the most influential couples in the alternative medicine community. Since Knauer already had American citizenship, Zhenya also obtained a US passport as his wife and officially became Indra Devi in the eyes of the law. However, as Goldberg points out, there is no evidence of Zhenya ever having divorced Strakaty.

Once in the US, Devi started writing. She published several books, debuting in 1953 with a title that speaks for itself: Forever Young, Forever Healthy: Simplified Yoga for Modern Living. 1959 saw the publication of the cult Yoga for Americans. Her timing was perfect, and her elucidations convincing. Both books achieved bestseller status immediately after publication and made Indra a star. She no longer had to worry about not having enough students.

After the successes of the 1950s, she spent the next decades almost constantly on the road: conferences, interviews, demonstrations, training sessions, book tours, meetings with readers, and with students aspiring to be yoga teachers. In 1963, the tireless promoter of hatha yoga published another book that also gained popularity: Renew Your Life Through Yoga.

Michelle Goldberg writes that Eugenie Peterson – Indra Devi – devoted most of her life to one goal: promoting yoga in the West. In the 1990s, when yogic exercises became an integral part of cosmopolitan urban culture, an indicator of a lifestyle that is both healthy and appealing, Indra’s dream came true. Yoga had reached the very heart of American popular culture.

It was largely Devi that made yoga a favourite sport among women: nowadays, women constitute 82% of all yoga practitioners. And yet in the beginning, let us not forget, it was because of her gender that she was denied the privilege of access to learning the asanas. In India, yoga was primarily a male pursuit. However, under the influence of a Latvian teacher and her famous American students, it practically became a symbol of the feminist movement.

In 1985, at the age of 86, Indra Devi decided to start all over again – this time in Buenos Aires. She lived the rest of her life there and passed away in her sleep. Born in the 19th century, she died in the 21st.

I used the following books: The Goddess Pose: The Audacious Life of Indra Devi, the Woman Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West by Michelle Goldberg, and Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice by Mark Singleton.

Translated from the Polish by Kate Webster