I was riding an elevator in my Berlin block of flats, when I looked at the manufacturer’s label and saw the production year: 1977. We are the same age, this retro-futurist, wave-shaped building and I. And I was born in a block just like this one, but in Warsaw – it also looked like a Star Wars spaceship.

When the Jelonki neighbourhood was built, our 12th floor flat overlooked cabbage fields stretching all the way to the horizon on one side, and the tapering silhouette of the Palace of Culture, Warsaw’s iconic example of socialist realism. Since early childhood, my sonic sensibilities were shaped by the drawn-out howls of the Nowotka Factory sirens – 6am sharp every day – and the rattle of passing trains. Later, the symphony of sounds was expanded by a mysterious gurgling in the pipes and the growling of lawnmowers outside. No wonder my heart was so easily won by the synth melodies I heard on the radio. The late 70s and early 80s marked the dawn of electro-pop and new romantic genres in music; space-like sounds were also permeating radio and television jingles. Urban landscapes, blocks of flats and early electronics became the genetic code of a generation.

The lyrics of the Polish greatest hits of that time spoke about this very situation, and the screens of black-and-white TV sets shone with a blueish glow in every window. Music charts were an inherent part of our lives since early childhood, and their lyrics stirred our imagination. Together with a friend from kindergarten, we’d take the stairs and run all the way up to the 12th floor, wheezing and pretending we were going through the Sahara Desert; it was our way of imitating the music video to a popular Polish song, Nie ma wody na pustyni (No Water In The Desert). We made it through the lower levels in panic; they said the guy who lived on the second floor kidnapped children to murder and eat them. Another time, in 1982, we blocked the corridor with sticks in our hands, pretending to be an army patrol. “Martial law!”, we exclaimed, demanding everyone we saw to show their permits to pass. Adults smiled at us ruefully, but we were in our element. We played soldiers and sang rock songs.

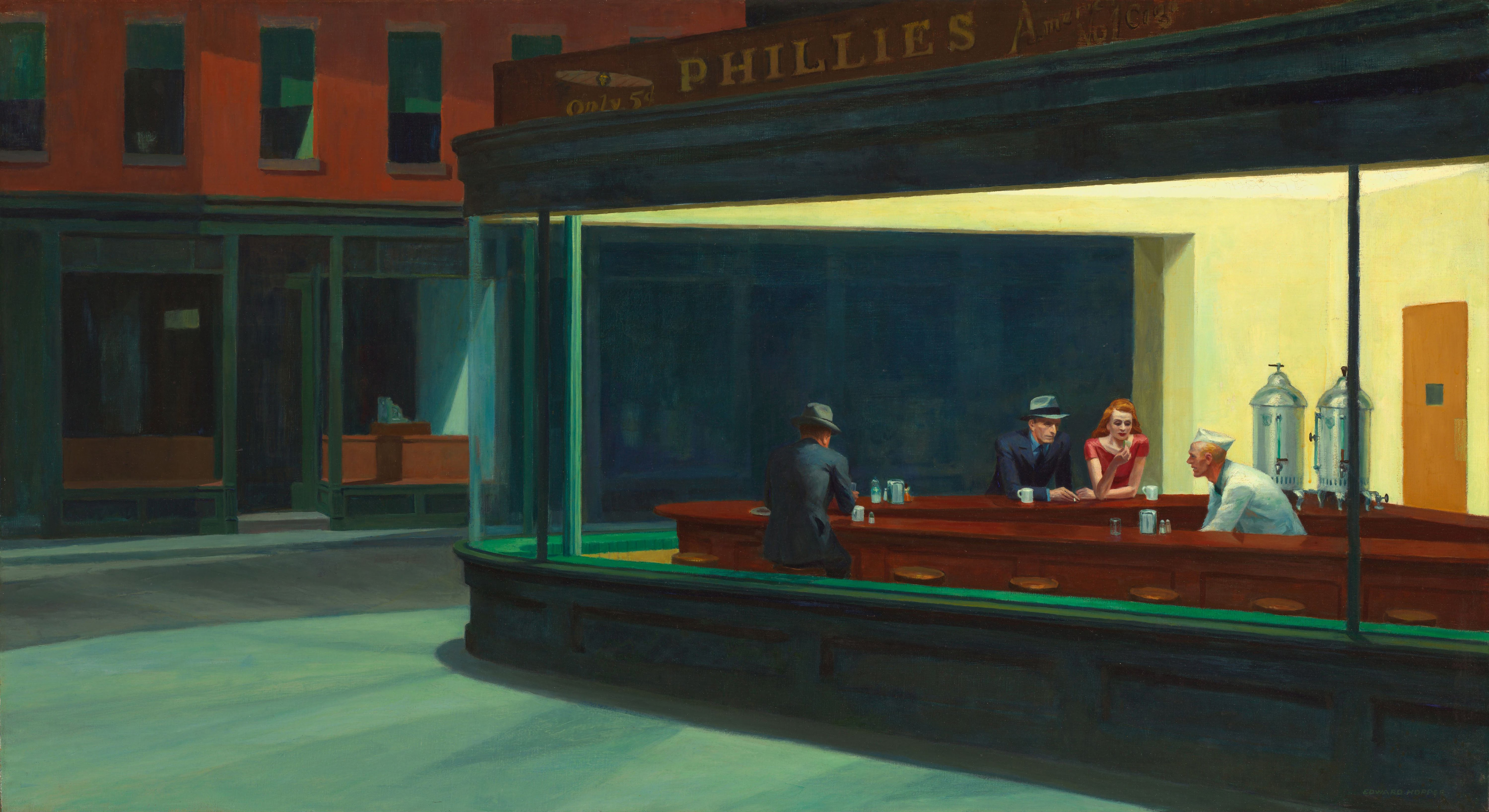

In the yard, we played hopscotch and we played with bottle caps; we dangled upside-down from the carpet-beating stands that were a staple of every Polish estate. Older kids experimented with saltpetre and organized pyrotechnic shows on parking lots. Urban estate life thrummed until the late evening hours, even in the winter. Snow and frost allowed creating vast ice rinks on parking lots by the blocks, always attracting crowds of neighbours. At night, we made all kinds of strange animals out of snow, we built castles and fortifications. One time, a moustached carpenter with a liquor-soaked face came to our flat to set up new wardrobes; later, we found out he was wanted by the police. Soon after, someone broke in, but that was normal back then. After that, we always left the radio on when going out. Soviet-made Rubin TVs glared with flagrant pictures, always showing that one frightening, hallucinogenic music video in technicolour, the one about the Sadist Dentist, in which the camp Polish diva Maryla Rodowicz impersonated Nina Hagen, accompanied by the band Devo. On Saturdays, we all queued for the only phone booth in the yard so we could make a call to the radio station and vote for our favourite songs in the charts. Surrealism was everywhere, the apocalyptic reality provided inspiration for numerous drawings and comic books.

As teenagers, we still roamed among the blocks, but it wasn’t until the 90s that the estates morphed into a proper concrete jungle in which street gangs and subcultures shared the same asphalt-covered spaces. Pinching people’s shoes was considered the norm, and the basic code for communication involved our home estate and social connections. Those times also had their soundtrack: screeches of car alarms howling when bald boys in crash tracksuits from the staircase next door broke car windows to take out heavy radios. The first buzzers were installed, so we pressed all the buttons at once and listened to the neighbours spew curses at each other. House parties with random guests and wild dancing would often get out of hand and turn into tornadoes, and our friends’ demolished flats were in shambles. We organized rehearsals of hardcore bands at home, carrying guitars, amps and drum sets from one block to another. During the rehearsals, our neighbours banged on our doors and radiator pipes that ran across all the floors. We would sit for hours on end on the staircases, in attics and laundry rooms, we carried cassette recorders everywhere. We bought Dramamine, the very same medicine our parents gave us for car sickness when we were little, and munched them to see the stairs walk across parks, and benches wag their tails at us. I loved taking acid from Holland and listening to Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on my portable Grundig while sitting on the staircase. For a few months, the first and only punk bar at my block functioned only thanks to the protection of the gloomy Sergey in a leather jacket; he was an Afghanistan vet dreaded by all the local chavs. Soon, life took on speed, guitars were replaced by Amiga and Atari computers, the era of techno music began, and after that, the first urban rap albums. The end of the 20th century on the block estates was also plagued by heroin addiction that took young lives by the thousands. But for many of us, it was already the time of moving away from home and escaping the homeland of grey blocks that were getting bleaker and bleaker.

Almost two decades have passed, but we still feel nostalgia for our real homeland of tall blocks. The echoes from the concrete staircases cannot be easily wiped from our genes. Many of us came back to the old neighbourhoods to live in the blocks, alone or with new families. The landscape has changed, it is now colourful and diverse, with Russian and Ukrainian teenagers, Georgian-Armenian bakeries popping up here and there. Neighbours of our parents’ age are already pensioners, standing grey-haired and stooped on tram stops, dragging their wheely shoppers to the street market, and walking their little dogs in the park. Sometimes, they are accompanied by their grown-up children, the same neighbourhood kids I remember from the early 90s. The skinhead from the block across from ours hasn’t changed at all either, still in his red suspenders and shiny Doc Martens, now a single father, taking his two little daughters for a walk with their fancy little scooters. The skinhead, with that thug face and a Yorkie on a leash, looks like an extra from a British comedy show. The people who remained in the block estates try fighting the passage of time, and they often seem to succeed. And even though the recently built local supermarket has already changed into the largest abandoned space in the city, they keep trying to live in the last decade of the 20th century.

Translated from the Polish by Aga Zano