“Among the stars we shall face the unknown.” The pathos of Lem’s prose was what people do when they face something they can’t understand. He saw that as civilization advances, these moments would come more and more often. In this, he was right. It turns out that humankind didn’t even need to go deep into outer space to meet alien intelligence it can’t fully comprehend. In fact, you’re probably holding it in your hand right now.

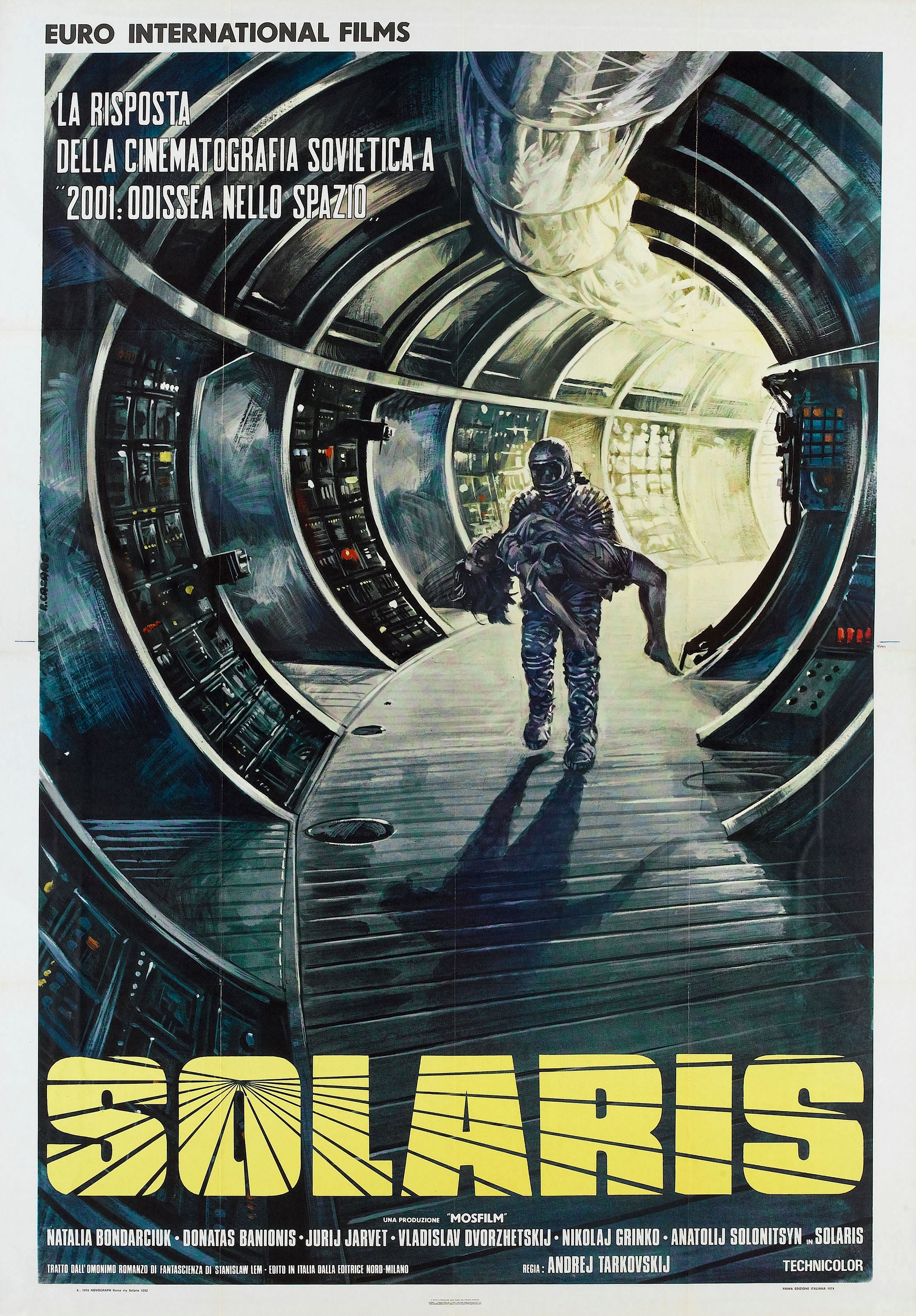

Solaris is arguably Stanisław Lem’s best known and most influential work, and Andrei Tarkovsky’s film version obviously played a significant part in its popularity, in spite of the fact that Lem was notoriously dissatisfied with the script. To reiterate common knowledge, the Polish writer disagreed with the Russian director’s focus on human characters, their back stories, and interactions (“Crime and Punishment in outer space”), and felt that not enough attention was given to the main hero, the mindful ocean with superpowers: what exactly it was, what precisely it was doing, and why? These questions aren’t easy. Solaris could be seen as a metaphor of God, who is, for a change, there and even answers prayers. If he believed it possible, wouldn’t this be what Kris would be praying for: to have Harey back? But I’m probably too godless to fully comprehend all the religious subtext of the book – and the beauty of Solaris is that it can be discussed in perfectly materialistic terms.

There is no doubt that it exists. People can observe and perceive its activity in the physical world, even though some of the things it can do, such as adjusting time and space to fix the orbit of its planet and bring people back from the dead (or, at least, create copies of dead people that are almost indistinguishable from their originals) are beyond our capacities. Its motivation is incomprehensible: it could be trying to grant the person his strongest and most suppressed desire, or recreating the person’s most traumatic experience by way of punishment, or, sensing that some neural patterns are repeating themselves, but are locked and suppressed, attempting to bring them into the open. But part of this incomprehensibility is our own nature: our most traumatic experiences, our strongest desires and our most developed neural patterns are usually the same thing. In fact, Solaris could be just as confused about the humans’ reaction to the ‘guests’. As it probably never had to suppress anything, it may fail to understand that some people may not enjoy it when their skeletons come dancing out of their closets; in fact, it probably can’t tell negative emotions from positive emotions.

Finally, Solaris is not as far from us as we might think. In fact, if we define it as non-human intelligence, whose information processing patterns we don’t fully understand, but who, within its sphere of influence, can play with time, space, and even create phantoms of deceased persons that are very hard to tell from reality, then, in a way, Solaris exists today on this planet.

Let’s talk about social media. Just stay with me for a while, I will explain. The biggest problem of social media at present is too many users creating too much content. If Facebook (or Twitter, or whichever platform) aspired to show you everything that your friends and the pages you’re subscribed to posted on a given day – as well as all advertising targetted at users matching your profile – you would probably need more than a day to read and watch it all. And so they don’t. Instead, they only show you the posts which – they think – would be interesting to you. Facebook is the best in this game, which is precisely why they have more users than any competitor, but all modern social media platforms do it these days.

How do they do it? Obviously, the only way to process so much information about 2.8 billion users is artificial intelligence. Lots of people, especially those whose innocent post was removed “because it violates our community standards” while someone else keeps saying perfectly outrageous things, think there’s too much ‘artificial’ and not enough ‘intelligence’ about Facebook – and it’s hard to disagree. Run an ad for an elephant hunt, and it is sure to land in the feed of an animal rights activist; post about your Pfizer jab and you’ll be seeing a bunch of anti-vaxxer content. The algorithms aren’t perfect yet, but this is only part of the story.

How does the AI decide which post to show to you? This is based on ‘engagement’, or how you interact with content. It goes far beyond Like, Comment and Share: the Holy Trinity of social media marketing’s early years. One of the most important metrics now is the time spent consuming content. Here you are, thumbing nonchalantly through your feed, and a picture grabs your attention. You stop to have a better look at it, you read the accompanying text, you give the pic a final look and swipe on. Yet for engagement-measuring robots, the picture may rank higher on the ‘content interesting for <your username>’ scale than your cousin’s daughter’s tennis practice video that you, without much thinking, marked with that pink heart and commented “How cute!” or similar. In the future, you are likely to see more content like this picture than your cousin’s videos. Yet you didn’t even like the pic. In fact, you hated it. But it triggered you, and that’s all the algorithm cares about.

Actually, it’s amazing how many other options to read your mind modern technology provides. They can track your activities in search engines and other apps. Or use the frontal camera of your phone to analyse your expressions as you flip through your feed. Or listen to your everyday conversations through your phone’s microphone. I’m not saying Facebook or other social media do all these things (except tracking, which they do only if you agree to it – or so they say). But the technical possibility exists.

Moreover, the algorithms can know you better than you know yourself, because you may not realize you’re interacting with or are triggered by certain topics, but the program can sense and record it. They don’t care whether your emotions are positive or negative. AI can’t tell, and even if it could, why should it? People often experience negative emotions for fun. Fear, for example, is something that humans are supposed to avoid, but what about all those people queueing for the latest horror movie or the scariest ride in the amusement park?

However, the emotions we perceive as negative – such as fear – tend to be stronger than those we perceive as positive. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but a useful evolutionary adaptation. Just picture yourself as an early hominid lazing on a sunny afternoon as your partner grooms you, when you hear a branch break in the bush. Those who let fear override the pleasant sensations and ran for the trees survived better than those who did the opposite. It is probably useful even now. Where would we be, if we didn’t worry about climate change, preferring instead to relax in the warmth of burning fossil fuel?

But this also means that you’re much more likely to engage with content that triggers your anxieties and fears, than with content that makes you feel good. A feelgood post is a like and a swipe; an anxiety-triggering one will make you refresh the app again and again, waiting for new developments. Which is, incidentally, the self-proclaimed goal of Facebook. The perfect world, according to Mark Zuckerberg, is where everyone opens the Facebook app immediately after waking up and doesn’t shut it down until bedtime. Facebook algorithms are set to make you do just that, which means they will give preference to the posts that make you feel anxious.

How exactly do they predict which post will engage you, which will trigger you, and which will outrage you? Amazingly, nobody knows. Obviously, the algorithms use keywords and picture elements. They also navigate by how people with similar profile to yours react to the post in question, which is why the more popular the post, the more reach it has – robots have more data for targetting. But the specific details are a mystery; Facebook AI is self-learning, and even its creators nowadays admit that they don’t have a clue how it does what it does.

Doesn’t that remind you of something? A non-human intelligence, following information procession patterns you don’t comprehend, is analysing your mind in order to find out your emotional triggers, and as it does, it retrieves your biggest anxieties and fears? The AI behind Facebook and other social media has all the essential properties that Lem envisioned in Solaris.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m reasonably sure that social media was not what Stanisław Lem had in mind when he wrote the book. But on the other hand, open your social media app, and what do you see? Images that appear for a fleeting instant out of the digital mist, images that may resemble trees, buildings or nothing in particular, a fantasy, or an infant that moves its head and legs and hands, but somehow not like a human baby, images that, under high resolution, consist of nothing, nothing except ones and zeros, zeros and ones, brought to you by an incomprehensible ocean of electromagnetic connections, that can the next moment show you a ghost waving from a video uploaded on this day n years ago?

Admittedly, as compared to Solaris, even Facebook is still a very young, weak and inexperienced intelligence. It operates sometimes so clumsily that users are more irritated than influenced by its actions. It can’t yet create, only choose from whatever users have uploaded. Although it can retrieve your memories, it is mostly in the form of the posts you made years ago. And, of course, it can’t yet reach out into the material world.

But Solaris also had no power beyond its own planet, and it’s an open question whether its ‘guests’ were fully material. They consisted of subatomic particles held together only by the incessant inflow of energy – one could argue they were simply an advanced hologram, a convincing, shareable illusion. As far as convincing, shareable illusions created with the help of elementary particles and magnetic fields go, Facebook could even teach the superocean a trick or two.

If Harey had had a Facebook account, where she’d posted about her life, the clothes she wore, the food she ate, her thoughts, ideas and reactions, an AI could continue it without any human intervention. Her reactions could be predicted just as Facebook AI now predicts your reaction to a post. Her posts would be created with software that can imitate any writer’s style. Her images, appropriately aged, could be added with the help of augmented reality to borrowed snapshots, to show how she’s travelling, shopping, eating out. A chatbot would carry on conversations in the comments. All it takes is enough information about the person – and it’s probable that the data in an iPhone which a user owned for a few years would suffice. If Kris was locked in a space station (or, why not, on COVID lockdown) and could only interact with the outside world through social media, how could he be sure she wasn’t there? Wouldn’t the illusion of Harey’s existence be as complete as her appearance as a ‘guest’ on Solaris?

In fact, within its field of gravity, social media can do as much as Solaris could. It negates space. Things and people both close to home and on the other side of the planet exist in the same location: the screen of your phone. It undoes time, throwing many minds back to an intolerant, fanatic and personality-cult past that humankind had almost seemed to have outlived. It has the potential to save the planet from a cosmic scale catastrophe, as it can adjust ideas, emotions and behaviour, just like Solaris fine-tuned time and space to correct its planet’s orbit. But social media’s influence spreads over much more than four confused, middle-aged, presumably white, males.

OK, if you don’t think it can actually save the planet, I share the scepticism. Facebook and its competitors exist only for one boring purpose: to make money out of advertising. At present, the most prominent effect of social media on people is an increase in tribalism, an escape into echo chambers, aggression and fear. But on the other hand, this is precisely how the protagonists of Solaris reacted at first: with fear and attempts to destroy its perceived cause. Yet even though they could have escaped this situation by flying to the satellite, they didn’t. Just like many Facebook users who delete the app and make a solemn promise never to log back on – only to break the promise shortly thereafter.

We have only just begun to realize the tremendous power that social media have over society, and a lot of alarmist texts call for a constraining of the evil algorithms. The question of what we are going to do, when we – perhaps for a purpose as lame as social media – develop an even more powerful artificial intelligence, is still open. Solaris, as well as Lem’s other books, may provide the answer. After the initial shock of discovery, and the first reaction to treat the unknown as a threat, the next logical step is curiosity, adjustment, and using the new possibilities. Just what Solaris’s protagonists did, or at least one of them attempted – and it is not his fault that it didn’t work out.