On coming to live in Warsaw five years ago to work as a teacher, my memories of the first months here are of darkened crawlspaces; the warren-like crevices of the city’s seemingly endless number of secondhand bookshops. A devotee of the weird and supernatural in literature, I spent my spare time searching for dusty arcanum hiding among the shelves. Before coming to Poland, I had read, and been captivated by, Miroslaw Lipinski’s translations of Stefan Grabiński, collected in The Dark Domain (Dedalus Press, 1992). I asked many of my Polish friends about his work, but was most often met with shrugs or blank stares. On my bookish outings around the city, I was attempting, rather falteringly, to trace the threads of the tradition that had produced such a singular writer. Was there a whole school of Polish supernatural fiction waiting to be unearthed? Why didn’t people seem to know anything about this writer who had had such an impact on me?

Throughout any number of halting conversations with kindly booksellers, somewhat bemused by this Englishman asking strange questions, a handful of names had arisen: the mystical poet, Tadeusz Miciński; the German- and Polish-language writer of decadence and Satanism, Stanisław Przybyszewski; the erudite fantasist, Antoni Lange. Looking a little closer, their concerns seemed somewhat divorced from Grabiński’s. These writers could all be situated, for better or worse, within schools and movements of the period, while Grabiński remained stubbornly inexplicable in the Polish literary landscape.

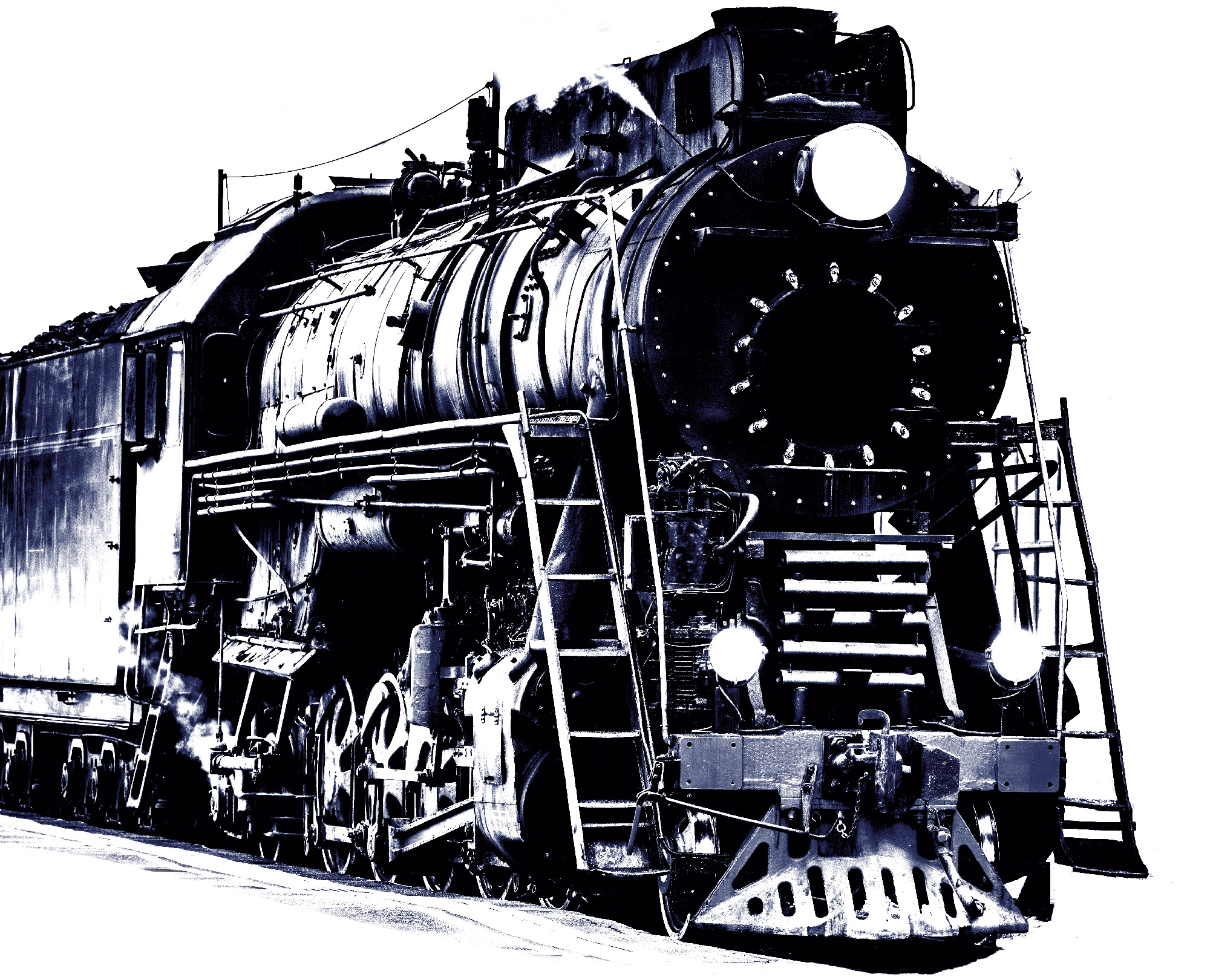

It was in a bookshop on Solec that I stumbled upon a 1980 edition of Grabiński’s collected stories in Polish, bound in a sinister blood red, and read the first lines of Artur Hutnikiewicz’s introduction: “A strange writer. Before him, there was no such figure in Polish literature.” Or indeed in any literature, it might be added. Resemblances to American writers have been pointed out, but to crown Grabiński ‘the Polish Lovecraft’ or ‘the Polish Poe’ – though it provides a viable shorthand for anglophone readers – is to lavish a kind of lukewarm praise upon him. When examined, neither of the comparisons stick. Grabiński’s horror is not to be found, like Lovecraft’s, lying dormant and tentacled upon the glaucous seabed; nor yet like Poe’s among towering Gothic spires, or resting beneath the tombs of candlelit mansions. In his best work, Grabiński’s is a decidedly living, earthbound horror – a horror of broad daylight we need only open our eyes to see. In this, he carves out his own, idiosyncratic niche within the genre. This is nowhere more apparent than in his collection of railway-themed uncanny tales, The Motion Demon (1919), the slim volume for which he is best remembered. Here, Grabiński turns his attention to the beating heart of capitalist modernity, the vast rows of cast steel spreading like a gargantuan cicatrix across the face of Europe.

Some influences are visible. After all, the lines of supernatural literature and the railroad have converged before. During Christmas time of 1866 in England, there appeared a collection of stories centred around the railway, entitled Mugby Junction. Included within it was “The Signal-Man” by Charles Dickens, echoes of which can be heard resoundingly throughout The Motion Demon. Written directly in response to his experiences in the Staplehurst rail crash of 1865, the tale concerns a lonely railway attendant haunted by premonitions, auguries communicated by the incessantly ringing bell in his signal box. A similar motif may be found in Grabiński’s “Ultima Thule”. From an isolated station at the end of an obscure line, the crackle of ticker tape telegraphs a message from the beyond in which we hear the final communication of a physical body undergoing its ultimate transformation: “Chaos . . . gloom . . . the incoherence of a dream . . . my body is lying there on the sofa . . . it’s slowly disintegrating . . . some waves are coming . . . large, bright waves.” Certainly, the dying cries of Lovecraft’s tormented narrators can also be heard here, but it is in Grabiński’s vision of humanity that the singularity of his vision is clearest.

The Motion Demon is populated by misanthropes and visionaries for whom rail travel is not a means of transport alone, but the far loftier impulse of “motion in and of itself, the conquest of space.” According to the philosophy of these idealistic men – for they are all men, and men of a lonely intellectual stripe – the common herd of travellers remains unconscious of the greater part of that which surrounds them, seeing only the mist of the waterfall, and ignoring the great sounding cataract itself.

Some have pointed to Henri Bergson’s concept of élan vital as Grabiński’s source for the elemental will that drives these characters in the mad pursuit of progress, speed and motion. It cannot be ignored, however, that those seduced by these notions often meet foul ends. In the opening story, “The Engine Driver Grot”, our hero romanticizes the purity of motion to such a degree that his duties fall by the wayside. Defying authority, he begins to deem it too banal an obstacle to the boundlessness of his will and ambition to make his stops at railway stations themselves. Losing his job, he boards a cab without authorization and feeds the furnace until the train erupts in a supernova of sparks and steel. In the title story, Grabiński personifies the “genius of motion . . . balanced on extended raven wings, surrounded by a swirling, frenzied dance of planets – a demon of interplanetary gales, interstellar moon blizzards…” For me, these are not images of progress, but metaphors of technological possession; a vision of Europe hurtling destructively into oblivion like a collapsed star. It is a vision we, on our dying world, would do well to heed today, when the horror of all our progress may plainly be seen.

Grabiński was a writer who found horror in the mundane, but he also found a new poetry in the places where other writers never bothered to look. In the story, “The Siding”, we meet the character of “Trackwalker Wior . . . formerly a scholar, thinker, philosopher, – thrown by the vagaries of fate among the rails of a scorned track – a voluntary watchman over forgotten lines – a fanatic among people . . .” Wior is the “king of sidings”, the one willing to cast his eyes over “a spurned offshoot of rail”, which lies “like a withered branch of a green tree, like the stump of a mutilated hand…” It is with a hint of tragedy that I read this description, for it calls to mind Grabiński’s ultimate fate, and his time in the spa town of Briukhovychi (near modern-day Lviv), where he lived out his final years in poverty and obscurity.

Despite the considerable number of film adaptations of his stories, the support of more famous proponents such as Karol Irzykowski and Stanisław Lem, and the translations into English, German and Portuguese, the mention of Grabiński’s name continues to evoke those shrugs and blank stares. This may change with the recent publication of Muzeum dusz czyśćcowych (Vesper, 2018), a selection of his tales in Polish. Could it be that his idiosyncratic artistic route strayed too far from the lines most journeyed upon? Even if it be so, I will continue to think of him every time I enter those darkened crawlspaces in search of the withered branches of literature which may yet grow again into stout green trees. And I shall not fail to think of him each time I board the train in Poland. I shall glance warily around the carriage, lest one of my fellow travellers be possessed by the “genius of motion”.

“The Motion Demon” (NoHo Press, 2014), trans. Miroslaw Lipinski

You can read Lipinski’s translation of the short story “The Sloven” here.