How can the world become a better place? Marshall Govindan tells Tomek Niewiadomski about living a simple life, uplifting thinking, the artist-wizard Salvador Dali, and a Christmas visit to an Arabian horse farm in communist Poland.

Tomek Niewiadomski: Can you introduce yourself – who are you and what is your experience of yourself?

Marshall Govindan: That’s a good question! The best answer I can give is my given spiritual name: “Sat Chit Ananda”, which means Absolute Being, Absolute Consciousness. Absolute Bliss.

Before we discuss Kriya Yoga, the Paramahansa Yogananda autobiography, self-realization, consciousness and more, I would like to ask you about your trip to Europe in the late 1960s. You spent some time in Poland. How did you find the reality of communism at that time, a reality so distant to what you had been used to? Could you tell us about your memories from that visit?

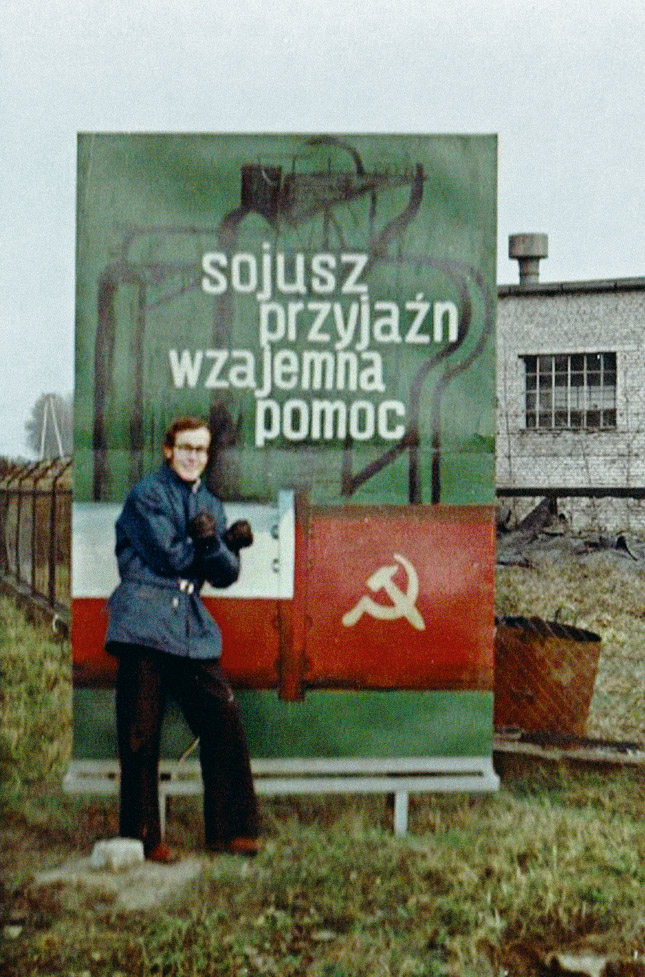

My third year of studies with the School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University brought me from the main campus in Washington, D.C. to the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. While there, I saw on a bulletin board an invitation for students to spend two weeks during the Christmas holidays at an Arabian horse farm operated by the Polish military. As the cost for lodging, meals and horseback riding was minimal, I enrolled along with a fellow student. We travelled by train. Our first overnight stop was in Prague. I vividly recall Wenceslas Square, because many of the buildings there were damaged by bullet holes from the fighting earlier that year when the Soviet army invaded. There was an atmosphere of mourning. In the dining room of our hotel we felt we were being watched by undercover security agents. I also strongly recollect the very dark, dirty and crowded train station in Kraków. In Szczecin, we stayed in a youth hostel for one night. In 1968, the Vietnam War was at its peak. Israel had conquered all of its neighbours the year before. There were students from North Korea and Syria in the same hostel, we said we were Canadians, not Americans, to avoid the potential for conflict. I was still sensitive, having been arrested and interrogated for several hours by the Stasi several months earlier during a visit to East Berlin, when I inadvertently wandered too close to the wall that separated the city.

Our hosts in Szczecin gave us a warm welcome to their home. I remember them informing me that they could speak freely with us inside their home, but not in public. The next day, they drove us for about an hour and a half to the horse farm. It was located in a forest. We stayed in a large brick house which was the home of the commandant, a colonel in the Polish cavalry. He told us that he had spent six years in a prison camp during World War II, along with other military officers. He told us that it was only one of two such farms in the world, and that the horses were raised for export to raise money from foreign exchange. I enjoyed, very much, my riding lessons. I remember visiting a food store in the nearby village, because there was so very little offered for sale on its shelves. I became friends with his daughter, who was about my age.

My fellow American student from Switzerland, Timothy Zamirowski, had a new Nikon camera and took many photographs, which I still have in an old album. I enjoyed the company of other visiting students from Moscow, who were, I was told, the sons and daughters of prominent Communist Party members. One of them was the son of the Soviet Union’s ambassador to China. During the Christmas Eve dinner, he challenged me to a competition drinking vodka. I don’t remember what happened after the third glass! But it was the last time I ever got drunk!

Also, during that same Europe trip, one of your friends invited you to his mother’s vacation home in Spain. A family friend was Salvador Dali. You were invited to Dali’s home on several occasions over a two-week period. In one of your books, you write that Dali and his wife Galla had a magical effect on you, and that you have seen the world in a new light ever since. Can you explain what actually happened during that time?

During the previous year, my best friend’s previous roommate was arrested for possession of marijuana and sentenced to prison for 20 years in a southern American state. He was the scion of one of America’s most distinguished families. In our efforts to help him, we came up against the venality of the friend’s family and the mafia’s attempts to blackmail the family. Disillusioned, I left for a junior year abroad program at the University of Fribourg, filled with existential questions. That was June 1968. But I had arrived at this university five months late, after making the most important detour of my life. While driving south through Carcassonne, France, I picked up a young Englishman who was hitchhiking. He invited me to spend time with his family in Cadequés, Spain, and to visit the famous surrealist artist, Salvador, a family friend, in the next village. During the two weeks I spent in Cadequés, I visited Salvador Dali and his wife Gala many times. These visits had a profound and lasting effect on me. Through their eyes, I began to see the world in a new mystical light. Dali was an artistic magician. While there I became friends with Philip Wellman, an electronic artist hired by Dali to build an invisible cage for flies using sound waves. The flies later appeared prominently in the ceiling-high painting he had just started in his studio. Philip and I spent the next four months together in Morocco, London and finally Paris, where we built and installed the first psychedelic light machines in discotheque clubs. I worked out a lot of desires during those four months before arriving at the university. It took quite a while to understand the depth of what had happened and what was happening within me. But I was changing course.

You were entering the path of spiritual search. One of the inspirations for you is Autobiography of a Yogi by Yogananda. In this book, you found answers to many existential questions that you had been asking for years. You describe the moment with the words: “I felt like I found a home”. Can reading the right book or meeting someone unusual have such a significant impact on who we become?

When you meet someone who is not identified with the ego-driven collection of memories, but with that which is the one constant throughout all of them, there is a glimpse of one’s own soul, that which has no preferences, that is fulfilled in its own being-ness. This meeting can occur even through a book such as Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, when it is infused with the author’s spirituality. That glimpse occurred for me during the two weeks I spent visiting Salvador Dali in his home in Port Lligat, Spain, in July 1968. He had started painting on a canvas that was more than four metres high. I learned that it was his first attempt to paint the psychedelic experience. I had never experimented with psychedelics, but I sensed that he was able to see an underlying reality from an uncommon perspective. Many years later, I saw the completed painting in the Dali museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. It is titled The Hallucinogenic Toreador. His dreamlike paintings infused with otherworldly and religious symbols pointed to something beyond the ordinary. I was 20 years old and fleeing a series of disturbing events that had profoundly shaken my assumptions about life, and my career plans as a diplomat in the US Foreign Service. The Vietnam war, the civil rights demonstrations, the racial riots after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, the countercultural movements all added fuel to my doubts and search for meaning. In hindsight, I believe that the previous year’s turmoil, and the hedonistic life in Paris, left me in a state where I was ready to turn away from the material world as a place of fulfillment, but ripe to be a spiritual seeker. This state is referred to in the Yogic literature as vairagya, or ‘dispassion’. It includes a thirst for the True, the Good, the Beautiful, and unconditional love.

It is difficult to interpret the Yogananda book unequivocally. Everyone who writes and creates philosophy reaches this level of consciousness; releases a multidimensional work to the world. Probably the best way to experience it is to consider it as a mirror and try to see in it what we are ready for. Does Yogananda’s Autobiography allow the reader to initiate what we call self-realization?

Yes, I believe that Yogananda’s intention was to attract persons, particularly Christians living in the West, to the practice of Kriya Yoga, with an understanding of Vedanta, the prominent Indian philosophic perspective. Yogananda emphasized a distinction between the little ‘self’ (or body-mind-personality), and the spiritual ‘Self’. The realization of this Self requires an expansion of consciousness through the practice of the meditation and breathing techniques known as Kriya Yoga, as prescribed by Yogananda. He referred to this realization as “Christ consciousness”, and he drew parallels between the teachings of Christianity and Hinduism. He also wrote many smaller tracts on metaphysical subjects, as well as on how to pray, how to know God, how to attract abundance and success. He was a pioneer in bringing the teachings of Indian spiritual Yoga to the West. The Autobiography was filled with many miraculous stories of little-known contemporary yogis with whom Yogananda had met or learned to practice Kriya Yoga. One of its shortcomings was that it included very little of the difficulties of the path, the resistance that human nature is bound to present to the practitioner of Kriya Yoga. Its purpose was to attract persons to the spiritual path of Yoga, not to provide a roadmap to reaching its goal of Self-realization. If he had provided such a roadmap, if he had for example, explained what drove him to run away from his own guru three times, how many persons would have had the courage or motivation to attempt to follow it themselves?

Thanks to self-realization, human life abounds in happiness and joy. Was helping to relieve the existential anguish of life the main motivation of Yogananda to teach Kriya Yoga in the West?

Yes, Yogananda’s intention included introducing the wisdom of India to the West, as a means to relieve existential suffering. Unlike Christianity, the promise of these wisdom teachings is not relief in a heavenly afterlife, but in one’s daily life, here and now. Furthermore, these wisdom teachings make a distinction between ‘happiness’, a passing emotion, dependent upon external events or conditions, and ‘joy’, which is the unconditional, blissful state of our true Self. Wisdom enables one to distinguish what is temporary from what is permanent, the body-mind-personality from the true Self, and the cause of suffering the source of lasting joy, according to Patanjali in the foundational text of Yoga, the Yoga Sutras.

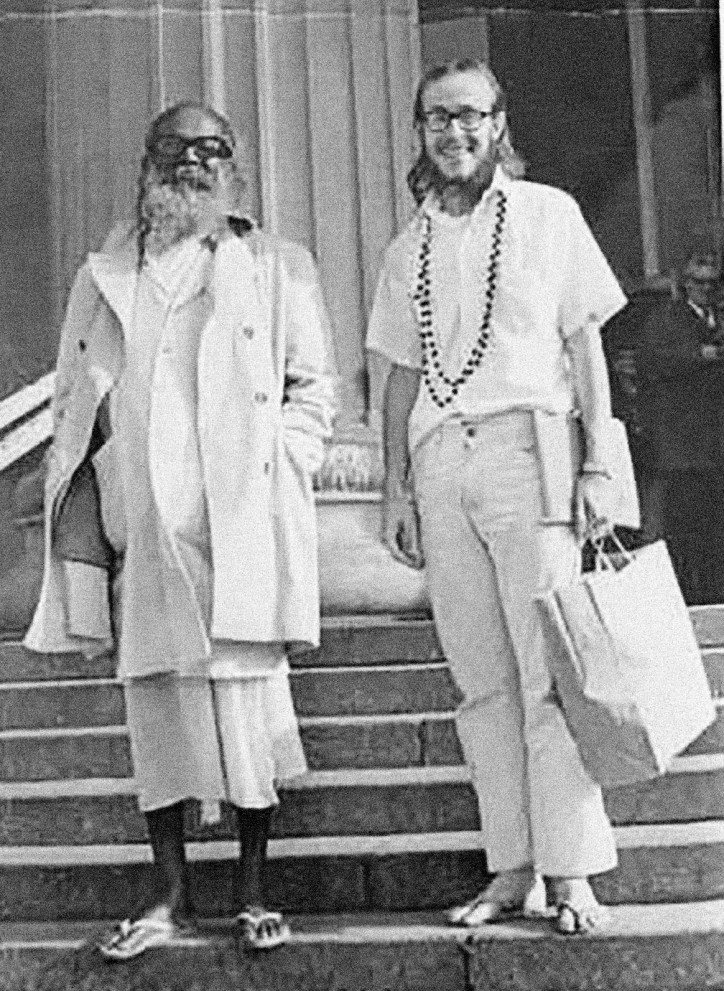

Finally, in 1969 in the Washington Free Press, a countercultural newspaper based in Washington, you found an announcement about Kriya Yoga classes, thanks to which you met Yogi Ramaiah, who inspired you with the maxim: “Practice yoga intensely, work in the world, not getting attached to it too much, and serve others.” This quote probably best describes what you have been doing since then, continuously for over 50 years.

Yes. When I began studying with Yogi Ramaiah, all I wanted to do was to meditate. But one of his first important teachings was “get a job”. He said: “Grab the first job you can find, and aspire for something better.” Initially, very few employers wanted to hire me, because of my long hair and beard, and because I dressed all in white. After my first year living with Yogiar in California, I was sent to Chicago to start a Yoga center. A year later, he sent me to south India to live in his ashram for a year. Subsequently, he sent me to live and work in other cities where he had started centres, including Washington, D.C. for four years, and later to Montreal, for the next 11 years. During these first 18 years, I practiced Kriya Yoga eight hours per day, worked at a job for eight hours per day, and spent the remaining eight hours per day in rest, teaching, and the routine necessities of life. It was an intensive period of spiritual development. During the next 25 years, I devoted much more of my time to teaching and writing, in the spirit of karma yoga, or selfless service, without attachment to the results. During this time, I gave more than a thousand seminars in 20 countries, to more than 12,000 persons. During the past six years, I am travelling much less. I am spending a lot of time teaching new teachers, and coaching and supporting the efforts of members of our lay order of teachers, Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas, as well as writing and publishing in a dozen languages, and developing our ashrams in India.

It’s best to influence others and create changes in the world starting with ourselves. Simply put, act as you would like others to do. Is this what self-realization is also all about?

Yes, when I abandoned my plans for career as a diplomat it was with the realization that the way to make a significant contribution to the world was one person at a time, starting with myself, rather than through government. During the early years, I was pretty self-absorbed in the practice of Kriya Yoga, not teaching others, as Yogi Ramaiah was not interested in having more than a handful of students who would practice intensively. When I left his organization, I wrote a book, Babaji and the 18 Siddha Kriya Yoga Tradition. It attracted a lot of interest, because it was the only book that continued what Yogananda’s book had started. So, I received a lot of invitations to teach all over the world.

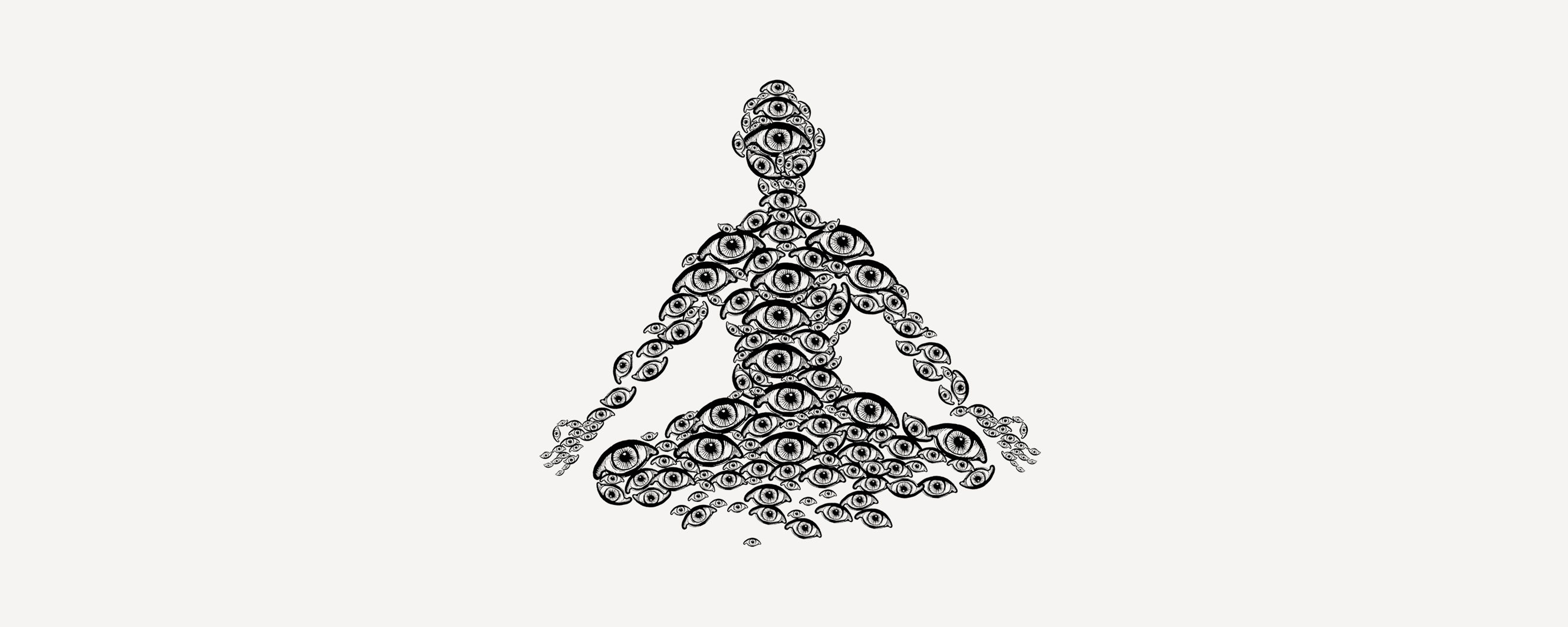

A few years later, I left full-time employment in order to devote myself to teaching and publishing. During this period, I also studied and published the writings of the Yoga Siddhas, and I developed a greater appreciation for the process of transformation required by an integral yoga, which includes the physical, vital/emotional, mental, intellectual and spiritual dimensions of human nature. Kriya means action with awareness, and it addresses all of these five dimensions. An approach to Self-realization which does not embrace the potential for perfection in all of these dimensions, but rather accepts a diseased body or a disturbed mind, is far from Siddhi, or perfection, the objective of the Yoga Siddhas such as Babaji. While Self-realization begins in the subtle spiritual dimension of oneself, all too often, the yogi attempts to simply ignore or deny, rather than to purify himself or herself of the resistance that manifests as negative habits, tendencies to dwell on memories, and manifestations of egoism, such as fear, anger, pride, lust and desire. An integral, or complete Self requires rejection of all of these forms of resistance, while aspiring for the True, the Good, the Beautiful, unconditional love, and surrender of the ego’s perspective to the perspective of the soul, the Witness. This requires bringing awareness into everyday activities, moment to moment. Egoism, the habit of identifying with emotions, thoughts and feelings, involves a contraction of consciousness. Yoga involves the expansion of awareness.

So you can say that yoga is more a spiritual exercise than a physical one? What is happening with yoga nowadays, if you compare it with the traditional knowledge of yogis of the East?

The word ‘Yoga’ has become a homograph, a word with various meanings. Its original meaning in the Indian literature refers to a ‘yoke’, a means or process to Self-realization, as well as ‘union’, a resulting state of unitary consciousness. But today in the West, the word ‘Yoga’ has been reduced to what is referred to as ‘modern postural yoga’, taught in a great variety of schools or styles, each one seeking to differentiate itself from the other in the commercial marketplace. This is ironic, because this differentiation contradicts to traditional goal of Yoga, the realization that there is only One. Yoga has been adapted to the needs of Western cultural values and lifestyle. Western culture worships material things, because it assumes that the more material possessions owned or consumed, the happier one will be. It also emphasizes competition, as a means to getting more material things. Competition fosters the need to be special, and this in turn, requires a lot of effort and produces a lot of stress. Yoga has been embraced in the West primarily as a means of managing the effects of such stress. For many, it has also simply been a means of losing weight, to look good and attractive. Some have discovered that the regular practice of Yoga improves their physical health, their ability to sleep, and gives them more energy.

What then distinguishes Kriya Yoga? Why exactly does this form of practice support the process of self-realization?

Kriya Yoga is an integral Yoga, which develops the potential of all five bodies, or sheaths: the physical, vital/emotional, mental, intellectual and spiritual. Modern postural yoga limits itself to the physical body and its health. Kriya Yoga includes the practice of the postures for the physical body, pranayama; the scientific art of mastering the breath, to awaken the potential power and consciousness, known as kundalini; dhyana, the art of mastering the mind; mantra yoga, to develop potential sources of inspiration available to the intellect; and bhakti yoga, the cultivation of love and devotion. By developing all five bodies, each of them can support one another in a synchronistic manner. While modern postural yoga can help the physical body, improve health, and help to manage the effects of stress, it leaves the vital and mental bodies in their typical disturbed and neurotic state. Nor does modern postural Yoga seek Self-realization, the development of the intellect, and the awakening of kundalini.

Such everyday practice must require a lot of discipline. Is it not the discipline that plays a key role in the feeling of happiness, which is, however, quite fleeting, and as something permanent is often confused with mindfulness?

The Yoga Siddhas say that you suffer because you are dreaming with your eyes open. Think of the happy moments in your life. And then consider what interrupted them? Some worry, some desire, some painful memory came into your mind, and like a cloud passing in front of the sun, your happiness disappeared. Where do these interruptions to your happiness come from? The Yoga Siddhas and modern psychologists would agree that they all originate in the subconscious mind. Like dreams, they come and go. Everyone manages to find moments of happiness. Moments of happiness arise when you fulfil a desire, during moments of pleasure, or when you receive good news. So, finding moments of happiness is not the problem. The problem is how to make happiness last. Everyone tries to find lasting happiness in things that do not last. Everything you experience is temporary. Everything changes. Your physical condition, your emotions, your thoughts, your circumstances, your relationships, your possessions, the weather, the dramas in your life, they all change. Even before something changes, you may begin to suffer from the anxiety that something may change. So, wisdom is to consider what never changes. What is it in you that never changes? What part of you has remained as a constant throughout all of your experiences? What part of you is the same now as when you were 6 years old, 12 years old, 21 years old, 35 years old 50 years old? When you turn within, and begin to become aware of it, you may refer to it as ‘I’. But it is not the thought ‘I’. It is what is behind the thought ‘I’. It is not a thing. It is not an object. It is the subject, the Witness to all of the moments of your life. It never changes. It is not limited by time or space.

The Yoga Siddhas, like a good physician, after diagnosing the cause of illness, also offer a prescription for your illness. They say: “The amount of happiness in life is proportional to your sadhana.” The word ‘sadhana’ refers to ‘self-discipline’, and more specifically in Yoga, ‘sadhana’ refers to everything you do to remember Who am I? and everything one does to let go of the false identification with what I am not. All practices in Yoga are aimed at creating the condition necessary for achieving these two objectives. This condition is referred to as ‘sattva’, or calmness, balance, clear understanding. Sadhana is essentially the cultivation of awareness. Awareness occurs when part of your consciousness stands back and observes or witnesses the activities of the body, mind and emotions. Such awareness is facilitated by being calm. For example, we teach the 18 postures with an emphasis on relaxation, concentration and awareness. Earlier, I made the distinction between ‘happiness’ and ‘joy’. The cultivation of awareness brings unconditional joy, the bliss of the soul’s perspective. Unlike happiness, which is temporary and subject to change, and conditional upon getting what you desire, or not getting what you don’t want, joy is available 24/7 if one adopts the perspective of the Witness. By practicing Kriya Yoga, action with awareness, one can test and confirm this assertion.

Why do we dream with our eyes open? I think we all perceive the world as very real.

What is real? That which always is. What within you always is? When one enquires deeply within “Who Am I?”, the underlying reality of Being Consciousness and Bliss becomes self-evident.

Why is silence so important in searching for Truth, Love & Beauty?

Silence is what distinguishes a spiritual tradition from religion. As discussed above, religion emphasizes forms, and because each religion has different forms, whether they be dogmas, texts, architecture, symbols or personalities, divisions are automatically created the moment you say “I am a Christian”, or “I am a Jew”, or “I am a Muslim”, or “I am a Hindu”. Ignorance breeds fear; and fear breads conflict. The spiritual dimension has no form. There everything is one. The cultivation of verbal silence brings mental silence. Mental silence is one of the characteristics of ‘Self-realization’. When the mind is silent, thoughts and sensation subside. One becomes aware of what is aware. This is referred to as ‘samadhi’, cognitive absorption. The object of awareness is awareness itself, consciousness.

What does it mean to be a spiritual person, but not a religious person?

Religion begins where spirituality ends. Religion begins with the attempt of the founder and his successors to describe what is essentially indescribable. The spirit has no form. Religion is all about forms: scriptures, dogmas, prayers, rituals, symbols, personalities and architecture. Their original purpose is to help others to follow a path that will lead to heaven in the Judaic-Christian-Islamic traditions, or to liberate oneself from an endless cycle of rebirth in the Eastern religious traditions. But once a religion exceeds more than a few adherents, these original purposes become subsumed under the needs of the religious institution, along with the need to control or manipulate adherents. All spiritual traditions give a privileged place to the cultivation of silence, because it is so effective in expanding consciousness and bringing one into a state of communion with the Supreme Being. Up until several hundred years ago, Europe’s monasteries were filled with monks and nuns. The Vatican, however, had mixed feelings about them, because if you are a monk or nun, you can communicate directly with the Lord, by cultivating silence. You do not need a priest, let alone a Pope, to do so. Consequently, the Vatican gave only limited support to monasteries, and instead encouraged activities that would bring more wealth and political power to the Vatican. Religion and spirituality can be mutually supportive. Spirituality can help those who are religious to learn to meditate, and to avoid magical thinking, guilt, fear of God, fanaticism and political division. Religion can support spirituality with inspiring literature, charitable or devotional activities, and education in the virtues.

Is return to simplicity a return to spirituality?

My teacher admonished us to follow the principle of ‘simple living and high thinking’. By eliminating desires for unnecessary material possessions, more of our energy could be devoted to the practice of Yoga, meditation and spiritual study. Consequently, we enjoyed freedom from worry over debt, the stress of overworking, over consumption, and competition with others. Today, there is a counterculture that encourages conservation, simple living, protection of the environment, vegetarianism, economic cooperation and the cultivation of higher consciousness.

When I think about the concept of higher consciousness, I ask myself another question: can science confirm the existence of higher states of consciousness associated with spiritual enlightenment?

Consciousness is the great mystery. It is not a thing. It is not an object. So it cannot be known. One can only be it. Science is attempting to understand it by associating it with activity in the brain. In recent years, brain waves of various speeds have been measured and correlated with various states of higher consciousness. These include the observation of yogis in the state of consciousness known as ‘samadhi’ while in a laboratory where their brain activities are monitored. Magnetic Resonance Imaging has enabled scientists to map the brain and to identify which parts of it are associated with higher states of consciousness. The mind is actually the play of consciousness within the brain.

In that case, can consciousness be the basis of everything that exists in the universe? In other words: does everything exist in consciousness?

Yes, the ancient Yogic literature says that conscious energy, referred to as Shiva Shakti, is the source that underlies all manifestation. Everything, whether it is physical, or as subtle as a thought, emerges from it, and dissolves into it, sooner or later. In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, it is referred to as ‘Ishvara’, the special Self, which is unaffected by karma (actions and their consequences), unaffected by the causes of suffering (ignorance of one’s true identity, egoism, attachment, aversion and fear of death), and unaffected by even the impression of desires. It has five functions: creation, preservation, dissolution, concealment and grace. These functions operate within the individual also. The Siddhas have a saying that encapsulates this: ‘The Lord is in you as you’.

When do you actually enter the spiritual path? Is the spiritual teacher not just a messenger whose role is to convey the message (i.e. the teaching), and people often make the mistake of admiring the teacher, neglecting to study and practice his spiritual teachings. And what about all this ego?

The spiritual path begins when you realize that you are nothing special. Ask yourself: “Am I ready to be no one special? Am I ready to experience nothing special?” Special-ness sets one apart from others. It is an artificial separation created by the mind. Self-realization reveals unity in diversity. It is the ego that wants to be special and that seeks happiness in new, special experiences. These provide at most a very transitory wave of delight in the vital body. The ego is also lazy. Consequently, it avoids making the necessary effort to digest or let go of its negative habits and tendencies. It has many preferences. One of its preferences is wanting someone to give it a special experience. There are many books that give a highly-romantic image of the spiritual path, with accounts of miracles and magical encounters with spiritually-advanced personalities, but which avoid describing the efforts required to overcome the resistance in human nature. These include negative emotions such as doubt, fear, pride, attachment and lust. Consequently, too often spiritual seekers make the error of continuing to search for a spiritual master who will give them enlightenment, or at least a spiritual experience, and avoiding the effort to apply Yoga’s technology to purifying themselves of the ego’s manifestations, which obstruct their potential for Self-realization.

So the cure for a better world is sharing, not just taking?

Who shares? Who takes? When you begin to access the level of your being where you realize that there is only one of us, you both give and receive with love and gratitude. You realize that the Lord is within you, giving and receiving. As your life unfolds, you see opportunities to give, to apply your intelligence to solving problems and helping the world to become a better place.

Are you happy?

Yes. I am happy. I identify with the Self. Remember what I said earlier about my understanding of ‘happiness’ as referring to a passing emotion in the vital body, and as distinct from unconditional ‘joy’, ‘bliss’, or ‘Ananda’, which is a characteristic of the Self, or soul. I have over the years learned to let go of the identification with the vital body’s movements, including desire, fear and anger, most of the time. There still remains work for me to do. It is a continuing process of purification. But I am happy also because I enjoy the world. I can be alone in one aspect of the Self, but I am not alone in the world. I have a wonderful life, a wonderful wife, Durga, who supports me in this work, and am part of a beautiful network of amazing Kriya yogis from all parts of the world. I live a rich life filled with love, meaning and gratitude for all that I am able to give and all that I have received. I feel truly blessed.

Student and teacher

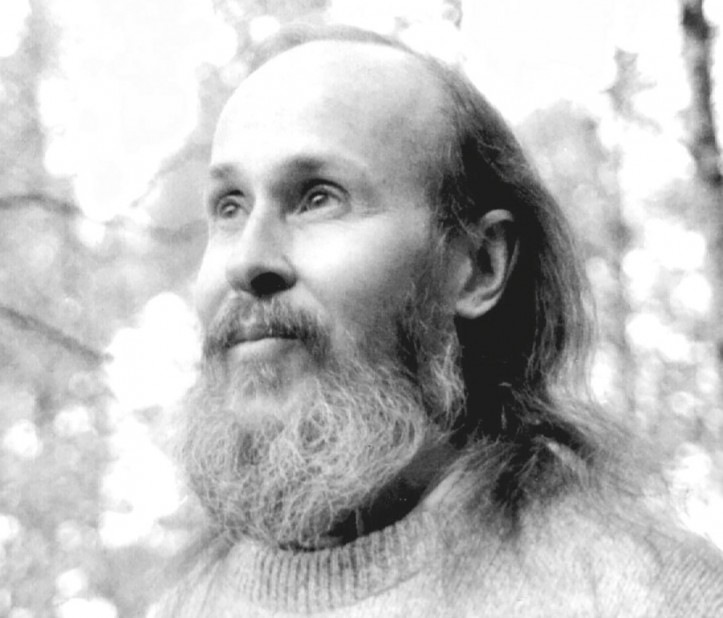

Marshall Govindan (Satchidananda) has practised Babaji’s Kriya Yoga intensively since 1969.

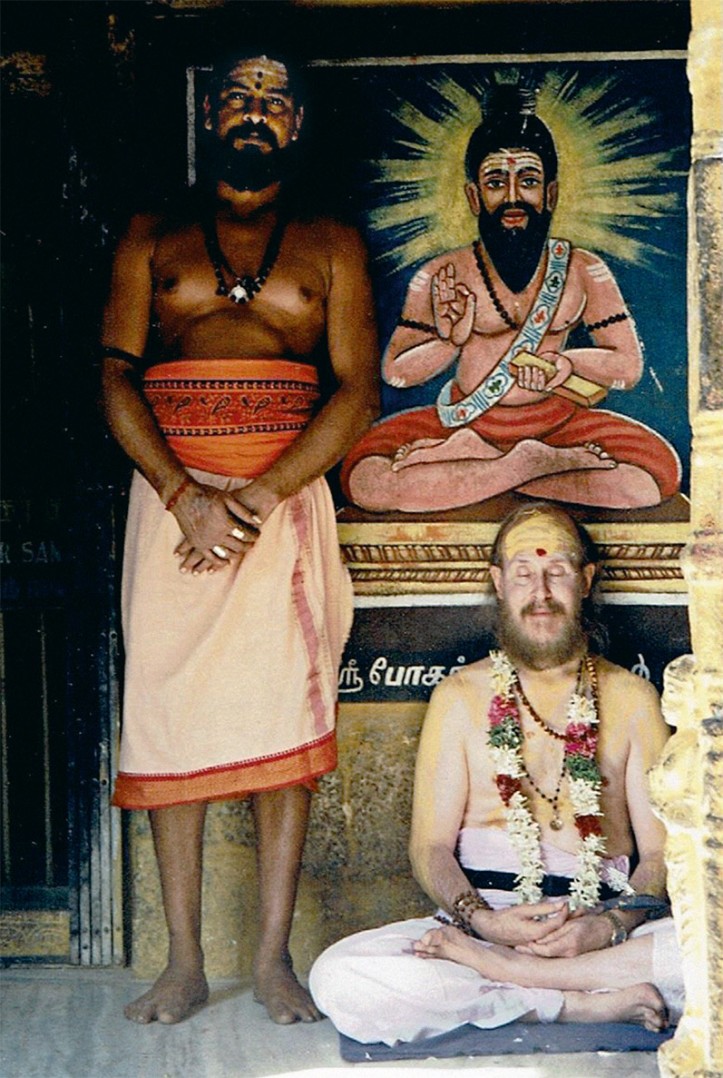

He spent over five years studying and practising Kriya Yoga in India under Yogi S.A.A. Ramaiah. For more than 18 years, Govindan helped Ramaiah to set up 23 yoga centres all over the world. During that time, he practised Kriya Yoga for eight hours a day on average, which allowed him to attain self-realization. When living in India, he learned the Tamil language and studied the works of the Tamil yoga Siddhas. In 1980, he participated in assembling and publishing the collected works of Siddhar Boganathar.

In 1986, he supervised the construction of a rehabilitation hospital promoting therapeutic yoga and physiotherapy in the South Indian state Tamil Nadu. Two years later, Babaji Nagaraj, the founder of Kriya Yoga, asked Govindan to take up teaching. This was a result of Govindan’s fulfilment of rigorous requirements necessary to initiate the adepts to 144 Kriyas given to him by Yogi Ramaiah five years earlier.

In 1991, Marshall Govindan wrote a bestselling book Babaji and the 18 Siddha Kriya Yoga Tradition, published in 16 languages so far. The following year, he established Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Ashram in St. Etienne de Bolton in Quebec. The ashram offers classes, seminars and retreats all year round. Since 1989, Marshal Govindan has personally initiated over 12,000 people to Babaji’s Kriya Yoga during intensive sessions and retreats in more than 20 countries. In 1995, he retired from his 25-year-long career as an economist and systems auditor to fully devote himself to teaching and writing about yoga. In 1997, Govindan founded a lay order of Kriya Yoga teachers: Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas, a non-profit educational charity organization registered in the United States, Canada, India, and Sri Lanka. As of today, the organization consists of 31 members.

Marshall Govindan is an author of a book and DVD Kriya Hatha Yoga: 18 Postures, The Wisdom of Jesus and the Yoga Siddhas, and Kriya Yoga Insights Along the Path. His book, titled Kriya Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Siddhas, was met with critical acclaim for its pioneering demonstration of close links connecting classical yoga to the Siddhars.

In October 1999, Marshall Govindan was blessed with the darshan (the beholding of guru or a deity) of Babaji Nagaraj near his ashram in Badrinath in the Himalayas. Since 2008, he has been building his own ashram there.

Since 2000, Marshall Govindan has been leading a team of researchers as part of a large-scale research project, regarding all existing literature on the Tamil Siddhars’ yoga. To date, the project has resulted in six research publications.

Marshall Govindan is a graduate of the School of Foreign Service Georgetown University, and of George Washington University in Washington. He is married to Durga Ahlund.

In 2014, he received a Patanjali Award for his outstanding contributions to the field of yoga, awarded by the International Yoga Federation/Yoga Alliance International, the oldest and largest yoga teachers’ association in the world. In 2012, the organization’s President said:

“Marshall Govindan Satchidananda is not only the most famous Yoga Master of Kriya Yoga in the world, but he also has done an amazing job for Kriya Yoga. I can only compare him to Paramahansa Yogananda. Govindan Satchidananda is the spirit of Babaji.”