The network of roads, bridges and tunnels built by the Inca adds up to tens of thousands of kilometres of impressive infrastructure, spreading out along the Andes and the Pacific coast. It was used by travellers and for goods transport, but it served primarily to transmit information and ideas.

Even though today the Qhapaq Ñan (Royal Road), covering almost the entire Andean region, is associated primarily with the Inca, the origins of the roads and the accompanying structures significantly predate the expansion of this group and the building of their powerful state. The results of archaeological research allow us to date the oldest remnants of the transport network to several centuries before our era. The trails that merchants and pilgrims most likely moved along were used and perfected over successive centuries, along with the dynamic social and political development of the western regions of South America. Particularly noteworthy are the routes from the period of the Wari states’ hegemony (more or less 600–900 CE), when the entire transport network was created and technologies were improved so that they guaranteed efficient movement of armies and central administrative control over the sprawling territories that were being taken over. The infrastructure of the day still covered the Andean region unevenly, depending on whether the area was inhabited by a greater or smaller population, and on the capabilities of the local labour force. But the main routes from that era were used as the basis for the systematically expanded network, which reached its maximum extent at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, when the Incas’ Tawantinsuyu state was dominant. Without a doubt, the Qhapaq Ñan was one of the key elements of the integration of the regions that found themselves under Inca rule.

Over mountains and rivers

The way the Inca builders fit their architecture into the landscape astonishes and captivates still today. Terraced fields, residential neighbourhoods, farm buildings and the palace estates of the rulers themselves are ideally knit into the surrounding landscape, and their structures are adjusted to the environment. It was no different with the road infrastructure: successive sections of the Qhapaq Ñan were built to fit in with exceptionally demanding topography, and operated in various climatic zones. The two main routes of the transport network cut vertically through the area of the Inca state: one ran along the steep, high sides of the Andes, connecting areas between today’s Quito and Mendoza; the other ran along the Pacific coast, connecting the territories between Tumbes and Santiago de Chile. The routes of the shorter roads between the main highways were laid out in very difficult conditions of the dry desert coastland, in harsh cold mountains (sierra) and in the hot Amazon selva (equatorial forest). On Haukaypata Square (today the Plaza de Armas) in Cusco, the political, economic and cultural centre of the Inca state, began the roads leading to the four corners of the Earth: to the four provinces (suyus) that made up the Realm of the Four Parts, Tawantinsuyu.

The effective management of such a sprawling state as Tawantinsuyu couldn’t have succeeded if it didn’t take care of transport infrastructure and guarantee efficient transfer of information. Intense work on expanding the Inca transport network lasted for almost a century, making the entire system functional and technologically cohesive. Roads from three-metres to as much as 20-metres wide, routes paved with stones, trails from beaten sand and gravel or simply narrow, beaten paths cut through deserts and swamps, run across steep mountain slopes and valleys, lead through the difficult passes of the Andes and also the hot, rainy forests of Amazonia. For the rains not to flood the roads or destroy their surfaces, channels and culverts were built along or across them. Depending on the terrain, the route was laid out using low stone walls and markers, or wooden and reed poles. In the areas of the desert Pacific coast, embankments were raised, and in the Atacama the road was marked by small stone mounds that served as orientation points. These mounds, known as apachetas, are also found in the sierra, where still today they stand at crossroads. Routes running through the mountain regions sometimes take the form of steep steps, laid out in stone blocks or cut directly into the rock. When needed, tunnels were also dug (equipped with ventilation channels), and the paths running along cliffs were safeguarded with railings and special side platforms. Colonial-era accounts tell us that trees were planted along many roads on the coast to provide travellers with a bit of shade.

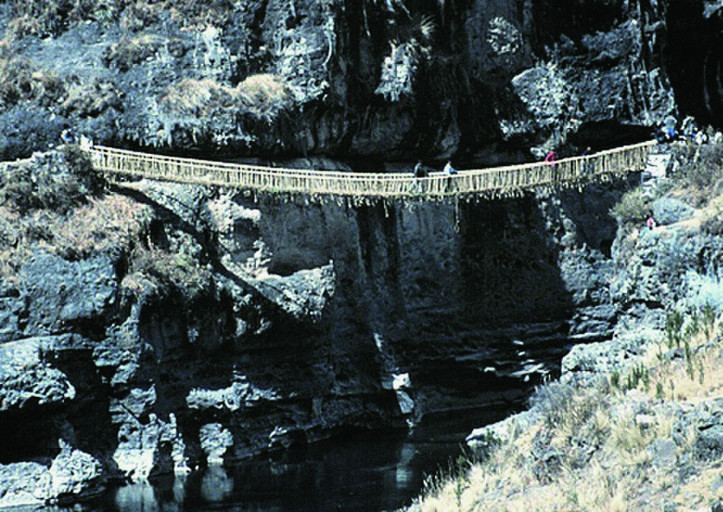

The road infrastructure was complemented by bridges. For narrow rivers, they were built from stone blocks or thick tree trunks; bridges were also built from gourds tied together with thick ropes, making up something in the nature of floating rafts. But the real challenge was building hanging rope bridges from textiles made from the plants available in a given area. Such bridges were mounted on huge stone buttresses, and the lines woven from flexible lianas could be tens of centimetres thick. The suspension bridges enabled efficient transport across deep canyons and dangerous rushing rivers. The only remaining example of such a structure is the Q’eswachaka suspension bridge in Peru, reconstructed each year using Inca technology, which connects the two sides of the gorge carved out by the strong current of the Apurímac River, more than 10 metres above the surface of the water. It’s 28-metres long and entirely woven from q’oya grass fibres and the branches of ch’illka shrubs.

The tampus, erected along the main routes of the Qhapaq Ñan between the valleys and the high mountain passes, were an exceptionally important element of the transport infrastructure. These small buildings were spaced one day’s walk apart and served as convenient places for travellers to rest and resupply. The practice of building roadside tampus was known already in pre-Inca times, which must explain their various shapes and sizes, depending on their intended use. The most magnificent ones, carefully constructed from hewn stone blocks, served as resting places for the Inca ruler himself and his entourage. Other, smaller tampus were erected for road and bridge inspectors, as well as administrative officials responsible for the labour force, or overseeing the quartering and equipping of the Inca army. The smallest tampus served as chaskiwasi – lodging for the Inca chaski runners, who were responsible for an efficient communication system across the entire sprawling area of Tawantinsuyu. Stopping places for the runners were located every three to six kilometres – a distance that young men covered in less than 20 minutes, allowing the fast transfer of information and small packages from one point to the next. In this way, news of events in even the most distant corners of the empire reached its destination, the central administration in Cusco, within a few days.

70,000 kilometres

In her History of the Inca Realm, now a classic, ethnohistorian Maria Rostworowska notes that a perfectly-maintained transport system was an essential condition for rapid expansion, efficient administration and achievement of political goals by the rulers of the Inca state. The roads primarily served the central authorities, and all the routes were under tight control by state officials. There was no right of free passage. Specific stretches of the Qhapaq Ñan were assigned to specific social groups: the routes had various rankings depending on who was allowed to travel on them. The most important ones, broad and in the sierra regions, meticulously paved, were for the ruler himself and his closest courtiers, the army and state administrators. Special narrow trails, the fastest possible routes between stopping places, were reserved for the chaski. Roads of lesser importance, local sections between urban centres and cultivated regions, were for ordinary residents. Sometimes two routes ran alongside each other – one exclusively for merchants and their animals, the other for military route marches or the movement of people resettled for labour or to develop new areas. Thus, the entire communication and transport network was built and operated according to the rules of economics and human-resources management, as well as the strategic needs of Tawantinsuyu’s rulers.

In the 1980s John Hyslop, author of what may be the best-known work on the Inca road system, estimated that the entire Qhapaq Ñan network may have measured about 40,000 kilometres. Today we know that in Peru alone, where most of the identified infrastructure lies, the figure is between 60,000 and 70,000 kilometres. Most likely the best-known section is the 43-kilometre Inca Trail, which leads from the Sacred Valley of the Incas to Machu Picchu. The road begins on the banks of the Río Urubamba, not far from Cusco, and reaches an altitude of about 2700 metres, at a place called Inti Punku (Sun Gate), from which there spreads out an amazing view of the restored Inca city.

With the coming of the Spaniards at the beginning of the 16th century, the Inca’s political system and the strong central power of Cusco broke down. The extensive network of connections, dependency and control that had thus far maintained the entire transport and communication infrastructure in such good condition thus ceased to function. During the Inca period, the Qhapaq Ñan had primarily connected northern and southern lands; during the colonial era, while the existing road system was used, what became more important from the point of view of demography and economics was transport connections between the sierra, where resource extraction centres were found, and port cities on the coast, from which ships full of cargo were sent to Spain. Thus many sections of the Qhapaq Ñan were still used, but even more were abandoned and forgotten, left to gradual destruction. With time, the experts in road and bridge construction and maintenance died out, and their knowledge died with them. The traditions of a rich ritual sphere also disappeared, such as the sacrificial ceremonies that during Inca times accompanied the building of new structures or the cleaning of main routes and drainage channels. Another contributor to the destruction of many roads was the introduction of new forms of travel and goods transport: shoed horses, wheeled transport and mule trains carrying heavy loads began to appear. The animals and wagons damaged the stone surface of the roads, and crossing suspension bridges woven from plant fibres became too dangerous, or simply impossible.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was investment in modern infrastructure: iron bridges, hard roads for wheeled transport, and a rail network. In many cases, the new routes ran parallel to the pre-Hispanic communication routes, or in exactly the same place. Simultaneously, urban centres were expanded, and new centres of industrial production appeared. All of this led to further destruction of some roads, and the abandonment of others. In 1929, construction began on the famous Pan-American Highway, whose path along almost the entire west coast of South America corresponds with numerous stretches of the Qhapaq Ñan, leading to it being irreparably damaged in many places.

Common heritage

Despite a process of destruction and degradation lasting several centuries, the Qhapaq Ñan, which we can comfortably call the world’s largest archaeological site, is still impressive for its range, perfect planning and engineering solutions. Nor has it completely lost its function. Sections that remain in good repair are used today by local communities. Inca roads are regularly used as the main routes for mule trains and the roads herders use for moving their llamas to pastures. In remote parts of the sierra, along difficult-to-access, steep Andean passes, they are in fact the only form of transport – there’s no other road infrastructure there. Small rural communities are often organized around more economically dynamic urban centres, which during colonial times were still set up near or in the same place as the pre-Hispanic tampus. For particular stretches of road to perform their function, local populations, based on the traditional institution of the faena comunal (common labour for the entire community) maintains the routes that are used, protecting and cleaning them. These initiatives fit into a cycle of annual ceremonies that are typical of each community, allowing residents of the region to integrate and to transmit their cultural heritage to future generations. For many, the Qhapaq Ñan is still today a “living road”, “the road of the ancestors”, to which they have a special spiritual bond. You can still encounter the conviction that “travelling along the Inca roads, you won’t get tired and you’ll always reach your destination.”

It’s estimated that more than 70% of the remaining Qhapaq Ñan infrastructure is found on the territory of Peru. This was the country whose representatives began work in 2001 to identify, document and reconstruct selected stretches of the Royal Road, and next proposed inscribing the network on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The Peruvian initiative won support from the other Andean countries whose territory includes parts of the Inca state: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia and Ecuador. In March 2002, during a meeting in the World Heritage Centre in Montevideo, the document “Prehispanic Andean roads and routes of Tawantinsuyu” was signed. The document stresses the significance of joint action to receive the nomination and the need to integrate local communities into the work. In the history of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, this was the first case where as many as six countries agreed to present the candidacy of a common cultural good. The years-long process of inventory and documentary preparations ended with a decision to inscribe the Qhapaq Ñan Andean Road System on the UNESCO list on 21st June 2014, during the 38th session of the World Heritage Committee in Doha, Qatar. It’s worth noting that the Qhapaq Ñan was placed on the list according to four cultural criteria. This broadens the perspective of defining the Qhapaq Ñan, not only in relation to its archaeological and architectural values, but also from the cultural perspective, particularly when it comes to transmitting knowledge from generation to generation, or – in the case of many communities that live near the routes – maintaining a traditional way of life.

After the nomination and the inscription on the UNESCO list, the Qhapaq Ñan, a symbol of political, economic and cultural unification during the time of the Inca, also took on significance as a symbol of the contemporary symbolic reintegration of the Andean region, bringing representatives of six South American states together in common efforts to secure, conserve and inventory it. The value of integration promoted under the banner of the Qhapaq Ñan can be seen during trips on designated stretches of the network, which for several years have been organized in Peru; some of them are international, running along the roads linking the territory of Ecuador and Peru, or Peru and Bolivia. The Caminatas – ‘journeys with history and tradition’ – organized by local communities with the help of representatives of local governments and central cultural institutions, are meant to promote knowledge about the pre-Hispanic communication network, strengthen bonds with the Andean region, and support action to protect and secure the remnants of the Inca Royal Road for future generations.