Closeness within the family doesn’t just happen; it’s the fruit of hard work. We long for the family idyll, but rather than take matters into our own hands, we prefer to sit at the table dreaming about happiness, which we usually don’t allow ourselves or others to experience.

Family can offer the allure of immortality: having biological children operates in the subconscious as a partial victory over death. That’s why we often treat our progeny as an ‘extension’ of ourselves. There’s nothing wrong with that, as long as at the same time we remember that children are separate entities and give them respect. The problem begins when we’re not aware that we need something from them that we can’t do for ourselves, or when we get angry at them for something that we don’t really like in ourselves. In that case, we’re most often dealing with one of two behaviours: either we’re ‘attaching ourselves’ to our descendants, to have the closest possible contact with ‘potential immortality’, or we’re ‘rejecting’ the child, to push away the fear of losing them. In both situations, it’s no longer about a descendant, but the ego of the parent and their biological need for what’s best in them to live on thanks to the child.

Striving for perfection is human – it’s natural that we require children to continue improving, but there’s also something pernicious about this behaviour. Here, the question of scale is very important. We shouldn’t allow our striving to blind us to the here and now. Let’s not forget that the persistent search for the ideal is most often accompanied by a lack of acceptance of oneself – the way one truly is – and for the surrounding world. This may lead to disorders in our perception of reality. Various defence mechanisms are set in motion, such as denial, projection or fixation. The mind may create a reality that suits us better, or one that we can simply accept. Everything that allows us to ‘escape from the truth’.

Emptiness and longing for love

The concept of the family assumes continuity of self-identity during transformation. And transformation of a family is multidimensional. Here we are speaking, if nothing else, about a transformation related to the births and deaths of particular individuals, meaning a generational change. A family can evolve thanks to the work and development of each of its members. Changes taking place in an individual change the entire family system.

Regardless of the position we hold in our families, we seek comfort and love in our dear ones. Unfortunately, we often fail to find it there. We fall prey to the delusion that we’ll find love ‘outside’ when we don’t feel it in ourselves.

Let’s imagine that we’re sitting at a large table, richly laid with potential for love and closeness. Usually we sit down hungry, not knowing that the others with us are just as hungry. That’s exactly how it often happens in the family. We’re fixated on our own needs, our own emptiness and our feeling of being harmed. In psychology, a feeling of need is often connected with the concept of a complex (e.g. Freud, Jung, Adler), which doesn’t allow us to fully see ourselves. For example, if we have not had sufficient experience of love in the family, a complex appears that will create the illusion that there is no love in us. What’s more, every time we try to get close to love, we’ll experience an unpleasant feeling – anxiety, rejection, discomfort – because we’ll associate love with something we didn’t receive, and thus also with pain. At those times, it’s worth reminding ourselves that this deficiency is an illusion.

Emptiness and a sense of scarcity are accompanied by panic at not knowing, not being able, not being worth it, not getting what we should… ‘No’ limits us, but in fact we ourselves say ‘no’, and we’re more and more fearful. Most often this is a generalized fear, which we can’t assign to anything concrete.

Heirs in the hierarchy

According to some, we have inherited divinity and fullness from the Creator God; for others, it’s in our genetic code. But it’s hard to deny that we are the heirs of something, if for no other reason than that we’re alive. So we can treat family in broader categories. A feeling of alienation in the world is just another form of the deficiency and emptiness we feel in the family. The scale is different, of course, but the psychological mechanisms evoking these feelings are the same.

Let’s consider even just the differences in ‘rank’ within a family. Once learned and remembered, they’ll translate into our behaviours toward people filling analogous roles. It’s never ‘one to one’, because the spectrum of relationships and attitudes is huge. Differences in ‘rank’ – whether in the immediate family or ‘in the world’ – aren’t conducive to intimacy. Building close relationships is always easier when it’s based on partnership and equality. It’s quite a task, because the awareness of ‘rank’ we have in a family structure is negligible. Most often, we don’t realize how strongly we actually affect other members. As a rule, we underestimate our ‘rank’, which sometimes results from a low feeling of self-worth, and sometimes is connected with arrogance and paradoxically becomes a form of self-exaltation – but both behaviours are examples of reducing rank. A person who knows their strength doesn’t have the need either to reduce themself, or to act superior. But the awareness of one’s position itself gives a high ‘rank’.

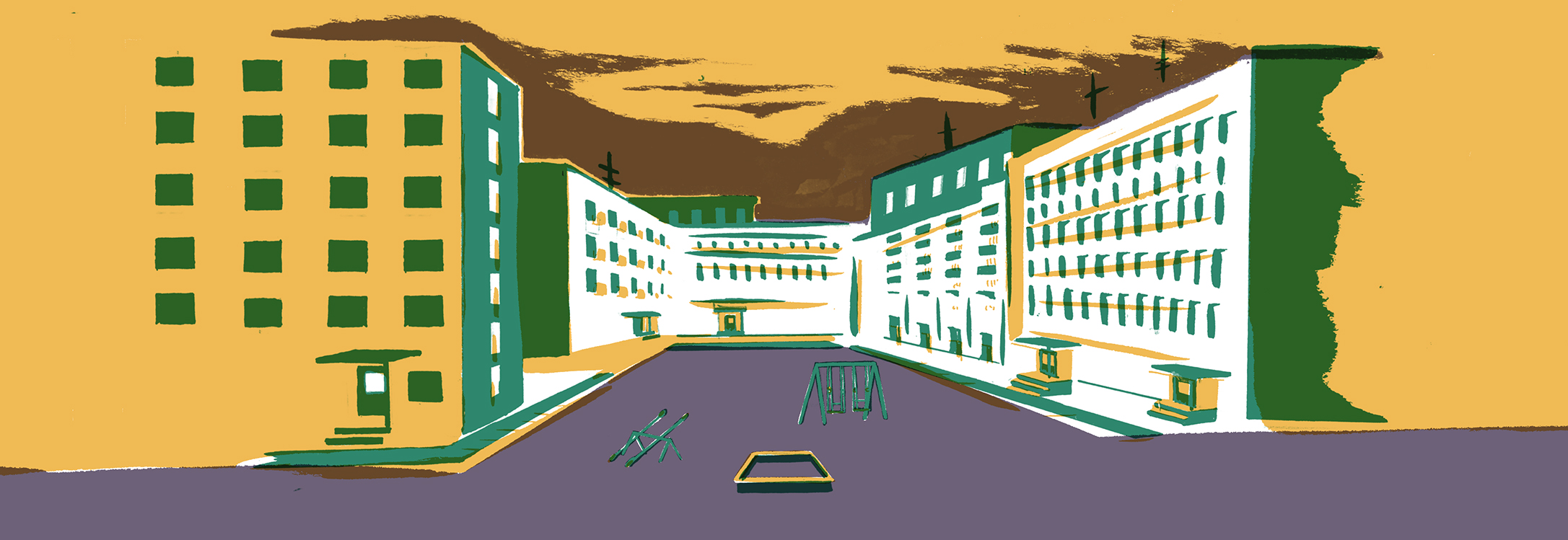

When speaking of rank, I have in mind one’s position: social, psychological, spiritual, situational (caused by a certain situation, e.g. an accident in which we behave heroically, even though we’ve never thought of ourselves as brave), financial, physical or structural (e.g. a position at work resulting from the structure of the company). The family we know is most often hierarchical, and each of these aspects counts. What’s more, the family system is based on mutually exclusive structures, because hierarchy and emotional closeness don’t go hand in hand. Hierarchy is by definition connected with distance. A feeling of authority and superiority towards another person resulting, for example, from age, as in a parent’s relationship with a small child, or position, an example of which is a child’s relationship to an ageing parent, carries the risk of abuse. This doesn’t mean that emotional closeness in hierarchical relationships is never possible. Much will depend on what definition of closeness we adopt, and also on what type of hierarchy. Nevertheless, it must be stressed that relationships that try to combine closeness and hierarchy are the ones where the greatest abuses happen.

Love without limits

It is only awareness of one’s rank, combined with the desire to create closeness, that is able to curb our ego, allow us to shed our complexes and heal our emotional wounds. But we must remember that in the end not everyone expresses the desire to create close relationships and to work on themselves to reach ‘the good’, broadly understood. Each of us carries their own baggage of experience and has certain limitations, which must always be respected. The compulsion for closeness with our families, even if it seems to be ‘good’ by its nature, remains a compulsion, and thus a form of violence, which is far from love.

The family system is impossible without closeness, even if it’s only biological or emotional closeness. Meanwhile, it can exist without hierarchy, but for this to be achievable, we would first have to work on our self-awareness and develop a feeling of unity within the family. The crisis of the family in our times, I believe, is related to a lack of balance: balance between our external and internal worlds. If our internal world lacks understanding, sensitivity, patience or forbearance, if we don’t cultivate closeness inside ourselves, it can’t exist in the external world, and thus in the family. Hierarchy, which is on the surface (external), causes distance and is connected with evaluation and ranking, and thus isn’t conducive to balance. On the other hand, equality, which as I understand it has the most in common with respect, requires effort: the ego must ‘come down from its pedestal’ so that we can be closer to another person. It’s not easy to go beyond your complexes and stop compensating for your deficiencies with your position in the hierarchy. But we should work on reducing the feeling of emptiness, bearing in mind that it’s an illusion. It’s also worth filling in the gap with acceptance and love rather than high expectations of others.