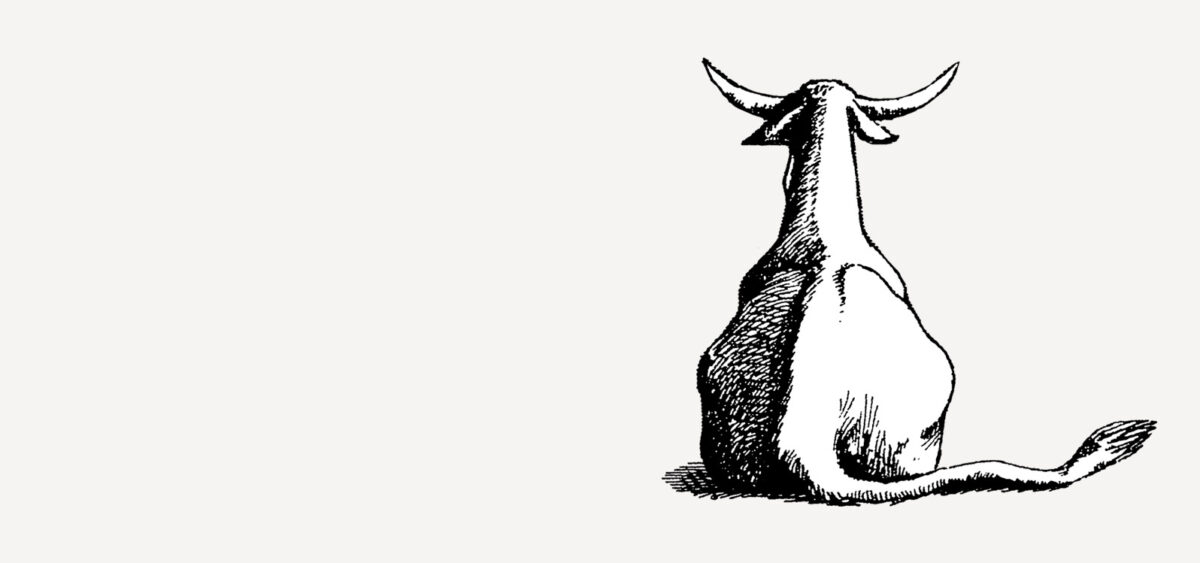

For ages, the Galloway livestock were part of the landscape of South West Scotland. But there are fewer and fewer old herds. A story about love for cows, beef and nature.

The time came to think of buying cattle. I began to ask around, but it was inevitable that I should be drawn to those black beasts which had haunted my childhood. I made a beeline to the Galloway Cattle Society for advice on getting started.

That Society has a wealth of members across the world. The breed has been sidelined by progress and change in the last half-century, but many folk are still united by their love of good beef and handsome cattle. I went to one of their meetings and was knocked flat by the depth of devotion and knowledge in that small room. It was humbling to realise that I had no idea what I was doing. Somebody asked me why I wanted to invest in Galloway cattle, and I struggled to provide an answer that wasn’t lightweight or sentimental. We haven’t measured our wealth in cattle for centuries, but the keeping of cows is not a game. Think long and hard, young man. My wife laughed that I was ready for the bind of parenthood but baulked at the cold reality of buying cattle. In my defence, I’d never been asked to explain why I wanted a child.

I stood back and looked again at what I wanted. There’s a slim financial case for cattle in conservation. Some people make it work because they play the grants and apply for the right subsidies, but curlews don’t pay the bills off their own back. Our beasts would have to do much more than drift around and help the birds. It was easy to get tangled up with fine details of conservation and wildlife, forgetting that everything depends upon on finance and a stable business.

I was brought up in a house which adored meat. Even in thinner days when my father straddled work with a law degree, we’d still enjoy cuts of beef that would shame the finest city restaurants. Our meat came to us from family and friends in sheets of rustling brown paper, straight from the butcher’s bench. My mother worked these bundles into hot, bleeding slabs of pink flesh, oozing gravy and fine scents. We were like drug dealers guzzling our own stash, and the bones would boil into stock for soup. Perhaps I picked it up from my father, but I still believe that the finest meal in the world lies between two pieces of bread: cold roast beef in a half-inch slice, decked in butter and a sprinkle of salt.

I burned with pride to hear Galloway beef being celebrated across the world, and I was tickled by the thought that I could produce food to match the finest of its kind. Maybe I couldn’t make conservation pay the bills, but there was clearly cash to be found in fine farm produce. I began to build a stronger case for farming, and I discovered a growing demand for traditional meat from rare breeds. Canny farmers add value to their produce because punters want to buy a piece of their heritage, a product which speaks loudly and goes beyond the daily shuttle of pink mince and vacuum packs.

I circled back to cattle with something like a credible plan. I could start with a few heifer calves and grow them into breeding stock, selling the best and eating the rest. This kind of farming is absurdly slow. Six or seven years would pass before I would have any animals to kill, and there was time to hone the specific details of my business plan on the hoof. And there was plenty of scope to throw in the towel and pass them on if it wasn’t working.

*

Brisk progress followed the first enclosures and the arrival of commercial cattle in Galloway. Forward-thinking farmers tuned in to the idea of improvement because there was decent money to be made. Cattle breeding became a local obsession, and Galloway farmers seemed to have a knack for it. In 1798, an anonymous English writer praised us for creating a beast which was not being ‘improved by the use of bulls from other quarters but by the unremitting efforts of breeders to use the best and most handsome cattle of both sexes, and by good feeding and management’. The genetic purity of Galloway livestock has been worn as a badge of honour ever since.

Beef was gathering steam. Look up the old records and you find a surge in cows across Galloway in the late eighteenth century. Our parish is called Kirkgunzeon (kirGUNyon), and it rose out of poverty like a comet as cattle caught on. A snap- shot in 1790 described a wild and rugged land with 2,000 beasts living on it. Less than fifty years later, we had over 3,000 cattle and every effort strived for more. Cash helped to focus the mind, and the English market was inexhaustable. Londoners raved about our beef, and demand grew in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham. In the days when hides and tallow made good prices, we were turning out the most valuable cattle in Britain, often by more than two pounds a head over other breeds.

Progress flowed on the back of our beef. By 1844, the Rev. John Crocket, minister of the parish, was proud to say that farmhouses in Kirgunzeon ‘which were formerly in a miserable state, are now comfortable and commodious’, with slate roofs and well-appointed yards. It was him and holy men like him who basked in the divinity of this progress. Galloway was making ground in the age-old battle against sin and wasteful- ness. They reckon that 30,000 head of cattle were crossing the border into England every year by 1800 Scottish drovers walked the cattle down to East Anglia so they could be fattened on English turnips and killed at Smithfield Market. That journey took the bellowing herds down through the heart of England, and the animals were a walking advertise- ment for the skill of Galloway farmers.

The original herds of Galloway cattle probably looked like a muddle, a churning mix of black, red, brown (dun) and white animals. Some were ‘belted’ with a white band around their bellies, and there were all kinds of other markings and patterns which lay somewhere in between. As momentum gathered, farmers began to focus on pure black cattle – ‘black, black and only black’ as the saying goes. The Galloway Cattle Society was established in 1878, and it set down many of the conventions which had become habit. They decreed that only three colours should be recognised as true. Red and dun were popular, but black was king. Black Galloways would go on to power the beef industry in the south of Scotland for the next century, and in time they’d cast a broad shadow across the world.

[….] eliminujemy szczegółowy fragment o odmianie riggit

A handful of riggit Galloways remain in Galloway, and I went to see my first beasts as an act of curiosity on a warm, sunlit evening in September. Restless swallows crowded along the telephone wires which connect Balmaclellan to the outside world, and the moor smelled of old bracken and dry moss. We climbed up through light fields until the land opened up beyond us. Hills loomed over a winding loch, the drab, familiar shapes of Corserine, Cairnsmore and the Garroch.

The cows belonged to Richard, and he is good with his animals. He’s gentle and softly spoken, and he chatted to them as if they were dear old friends. He checked off their details on a folded piece of paper, then he clasped his hands quietly behind his back. Some heifer calves were for sale, and we could have stood barefoot in the soft grass as they walked between us. Of course I was smitten. These beasts smelled of cud and honesty, lightly shaken from the leaves of a history book. I drank them in and found that they were home incarnate; a place conjured up in curls and long, soft eyelashes.

I warmed to the riggit colours in a heartbeat; blacks and whites swirled together like a freshly poured pint of stout. I’d always been dead set on black Galloways, but there was no way I could ever walk away from these animals. I chose one calf for her markings, which were a perfect replica of the old Garrard painting of 1804. She was blotchy, soft and perfectly gorgeous. I picked a second for her shape, a broad, tubby barrel with a wrinkle of fat around her neck. Richard shook my hand and we sealed the deal, but here was a squeak of dishonesty on my part. I didn’t have any money to pay for these calves, but I reassured myself that there were still three months to worry about that. The heifers were young and couldn’t leave their mothers until Christmas, giving me enough time to scrape some cash together. Three months keened my appetite to a fever pitch. Having reconsidered his options over the autumn, Richard telephoned again and offered me two more beasts for sale. I went to the bank.

It turned out that my first heifers were absurdly independent. I was ready to care for them, but they didn’t need anything from me. They came out of the lorry, vanished into the whins and I didn’t see them again for a week. I fell to tracking their movements like a big game hunter. That makes them sound nervy and wild, but really it was a knowing adolescent coolness which kept them at arm’s length. I’d been told that they would be ‘low maintenance’, but I found that they were ‘no maintenance’. They made it clear that my duty was to feed them and then get lost.

One of my calves was the most beautiful animal I’d ever seen. She had a white head with black eyes, black ears and a black nose. We call these markings ‘points’, and here’s the seed of beauty. ‘Well-marked’ cattle start with deep, expres- sive eyes which glitter in dribbled mascara. Beyond this, riggit markings can be almost anything. The main requisite is a white stripe which runs from the withers to the rump, but my favourite was mottled all over. Her sister had a black head and a white arse. The third was dappled with blue roan and the fourth was daubed with blocky, geometrically perfect markings with hard lines. They were a jumble and I adored their details, but I couldn’t ignore the fact that these animals aren’t supposed to be viewed up close. Pat and dandle them all you like, but Galloways look best in a middle distance of tumbling moorland and rising cloud. At the range of a mile, riggits make a smattered line of black and white to make your heart sing. It is possible to breed red riggit Galloways, and the colour is popular with English breeders. I was struck with black riggits because they’re bound to the same spartan aesthetic as granite and collie dogs; even our house is white with black lintels. This landscape swings in a million shades, but black and white is utterly permanent.

Six months passed before I’d even touch my calves. Bound up and confined in a steel crush, the vet drew blood samples for a health check. The needles bent at the hardness of their skin and the blood flowed dark and thick into a plastic tube. I waited until the vet was looking away, then reached in shyly to touch my beasts. They were warm and rough and their hair was filled with whin prickles. A smell of sweat and cud tingled on my palm. Even at hip-height, they were bigger than toys and could tread me into the mud without a shrug.

It’s often hard to draw a line between Galloways and Galloway itself. The cattle were formed by that rough, grassy land which runs across the Southern Uplands like sack cloth, and yet the moors themselves are a product of their grazing. These hills were an ancient forest in the days before men came and began to reorganise the place. So it’s fair to reckon that the moors and the animals are really just the same thing. And if you’re happy with that, then it’s not such a big leap to imagine that the beef is really just a fine concentration of that damp, empty void between low clouds and the peat moss.

The bond between hills and beasts feels ancient, but there’s something horribly fragile in that link between cattle and moorland places. The world began to move away from Galloway cattle over the last half-century, and many of the old herds have now vanished. It should be no surprise that cow-made places have begun to misfire and underperform as cattle withdraw. Our wide hills are no longer feeling themselves, and it’s starting to become clear how deeply the old connection ran between hill country and curly beasts. Galloways gave us more than just meat; they were the heart of a very old system.

I remember the pyres which followed the Foot and Mouth outbreak in 2001. The streets were filled with soldiers and vets in white overalls. A sickly smell lay in the glens, and smoke poured up from stiff-legged heaps of dead stock. If a farm tested positive for the disease, all animals were killed within a three-kilometre radius. The awful diktat raked through the landscape and brought a sudden, jarring end to many famous beasts.

Hills are no place for hurry or quick changes. Farming this land is like walking across a broad spread of open ground. You lay your plans on a distant rock, then set off towards it. The work rolls by and every step takes you irre- sistibly closer to the destination that you saw in its wholeness before you started. You can get away with angles and quick thinking on good ground, but the hills demand a slow and stable plod. Fertility grows, habits form and the land is teased into action. People and animals pass down their wisdom between generations. Cows had been in the hills for thousands of years; far back beyond the first farmers. The culls snapped a million ancient threads and left hill farmers with sudden decisions.

A friend in the Glenkens still mourns the loss of his cattle which used to walk the five-mile track to and from his hill with- out any pushing or encouragement. The brave old cattle were driven by nothing more than a pulse of memory and routine. All he had to do was walk behind them and close the gates. They’ve been gone for years, but you can sometimes hear those old herds moving in the darkness. Their habits are worn into the soil like hoofprints, and calves learned the land from their mothers. Farmers were compensated for their losses, but you can’t replace that weighty heft of shared memory.

Stripped of cattle, the land took a new path. Cows had been smashing up bracken and deep beds of rough grass for centuries. They kept a balance and built a blend of freshness in the undergrowth. Curlews loved that mix, and they thrived in the wake of old cattle. They riddled the rich mud for worms, and their chicks fattened in a fairyland of insects and spiders which hummed around the dark pats. But without the munching mouths, heather began to drown in ribbons of white grass and the wildflowers thinned to exhaustion. Curlews were baffled because the ground grew thick and dull beneath them. The cattle had sustained a fine, subtle footing in a fragile world, but they were burnt and buried and everything changed.

We can never measure the loss of old hill cows. We’re only just beginning to see that our trusty old natives called for a kind of farming which improved everything it touched. And now our wildlife is hamstrung without them; the crashing decline of birds like curlews is just a symptom of our with- drawal from tough, tricky places. Now it’s easier to make the hills into something new, and policy makers are nudging farmers to ditch their livestock and sow their hills with commercial forests. This is the final straw for curlews. The birds have lived beneath open skies for too long to tolerate trees. They abandon the hills where plantings grow, and the survivors fail and rot beneath strange new pressures from the trees.

Change usually comes in a long, nibbling flow of details. We look up one day and realise that we’ve been travelling all the while. It’s harder to fathom change in Galloway because it came in a single, unchewed lump. We moved from ancient, primor- dial woodland to farming over a thousand years. We turned our hand to cattle over several centuries. Then we became a commercial softwood forest in thirty years.

And people say nothing happens in Galloway.

This is an excerpt from Patrick Laurie’s “Native: Life in the Vanishing Landscape”.