Aleppo used to be an intricate tapestry of chatter, crowds, shaded courtyards, temples and baths, history and the present. In a word: a community. A few years ago, its markets turned into trenches and its gardens into graveyards. Nonetheless, in one of the longest-inhabited places in the world, hope never dies.

Midday, boiling hot. My friends and I get off the bus on swollen legs. We’ve just made a week-long land journey from Poland via Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey all the way to the Syrian border, where we will now spend long hours waiting for an entry stamp, under the piercing gaze of portraits of Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar. It’s summer 2001; Assad senior died the previous summer and his son assumed power. We understand little about this, maybe only that we’re about to enter a country in which half of the world’s websites are inaccessible and every waiter can be an agent of the regime.

Aleppo welcomes us with hubbub and dust. But its inhabitants are paragons of friendliness. Vendors of sweet coffee, as well as self-appointed guides and drivers, are all hospitable and curious. They pile on the questions, offers, invitations to talk in French—they’re so glad to have someone with whom they can converse in the language they learned at high school, but use rarely. No, it’s not about money. In Syria—at that moment, I was certain of this—we’re welcomed by the joy of encountering newcomers, although ultimately we don’t represent anything promising. Just three female students and one guy, a little older, ginger-haired.

Around the Clock

We sleep the cheapest way—on the roof of a little hotel somewhere in the heart of the old city. We play backgammon and smoke the hookah with some Syrians until late at night; below the city rustles on, working and busy at all hours. We doze off, woken up again and again by the noise of store shutters (some businesses are closing, some are opening), laughter from cafés, the roar of engines, and the shouts of men unloading trucks full of tires in the dark. Aleppo never sleeps. In order to stock its bazaars, dispatch sacks of wheat and oats, receive spices, send off fabrics, fruit, and vegetables, one needs to work all the time. Even on the brink of the new millennium, the city—held for decades in an authoritarian grasp which cut it off from the world and its cosmopolitan past—remains true to its heritage. Aleppo lives as long as it trades, talks, and relishes poetry.

We wake at sunrise. The fiery sphere jumps over the horizon, immediately burning and dazzling. We look for respite from the heat in the nooks of sandstone walls, in shaded courtyards, in three-hundred-year-old gates, and among the stalls at the endless souks (markets hidden under stone vaults). Aleppo is a city of secret alleyways, covered backstreets, and murmuring fountains, a mixture of the private and the public which isn’t immediately clear to us. Shared alleys end up leading us to private family backyards and into dead ends. Nobody chases us away; our embarrassment is met with smiles, invitations for tea and a chat. Nowhere else will I see architecture so deeply infused with trust, so connecting.

Outside the ancient walls, the city was completely different—in the style of Le Corbusier. Wide streets were lined with tall blocks of young residential districts. These were a response to the 20th-century demographic boom, when factories and craft workshops attracted people from the countryside (Aleppo’s population increased from 300,000 at the beginning of the century to around 2.3 million in 2005). As opposed to the traditional Arab urban plan and its attendant network of unique human relationships, the tower blocks were a way to divide the city’s inhabitants, weaved together across centuries; to chop their complex bonds into pieces. After the civil war broke out in 2011, Syrian architects spoke up: they ascribed part of the blame for social division and its bloody consequences to architecture like this.

According to UNESCO, Aleppo might be the oldest continuously inhabited city on Earth—it is over four thousand years old. During that time, it has been destroyed by wars, earthquakes, and fires, but according to historians it has a unique gene of survival and adaptation. To those who study the massive fresco of history, the ongoing civil war in Syria and the dreadful damage it has dealt to this magnificent metropolis are just one more tumultuous episode in its continued existence. Another tragedy that Aleppo will eventually recover from.

Built by Rome, Changed by Islam

The first mentions of Aleppo’s existence can be found in Egyptian documents dating back to the 20th century BCE. The city flourished in the 18th century BCE—its advantages included its location on the banks of the River Queiq and fertile soil, as well as the fact that it was roughly halfway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates. In the Hellenistic period, the Syrian city was an important stop on trade routes from Asia to Europe. It owes its unique architecture to the Greeks, and then the Romans, who added it to their empire. Ancient rulers from Europe built the fortifications with eight gates and the network of perpendicular streets which still forms Aleppo’s core. In the third century BCE, a temple of Hadad—the storm god—was built on the hill located at its center. The Romans marked out a wide thoroughfare through the middle of the city; next to it they erected a magnificent temple of Jupiter. Subsequent rulers added their own corrections onto this clear plan. From the seventh century CE onwards, Muslims ruled the city. This was the beginning of many centuries of strife, fighting, and competition between various dynasties, including the Fatimids and Seljuks, as well as the European Crusaders.

The Muslim architecture and lifestyle chopped up the clear arrangement of Roman streets and turned it into labyrinths of narrow alleyways lined by low buildings. Covered markets—souks—with their thousands of shops began to spread on both sides of the city’s main transport route, and this was all connected by magnificent gates. Souks specialized in selling specific wares: from pistachios and meat to olive soap. During the subsequent centuries, they would form one of the most sophisticated urban tapestries and the largest covered marketplace known to humanity. If this intricate architectural embroidery can be compared with anything, it can only be ancient Damascus, Constantinople, or Rome. In 1986, the oldest part of Aleppo became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As a result of the battle which took place there in the years 2012 to 2016 between troops rebelling against Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the leader’s loyal army, as many as two-thirds of these buildings were severely damaged. The rest were destroyed in their entirety.

An Ideal Turned to Dust

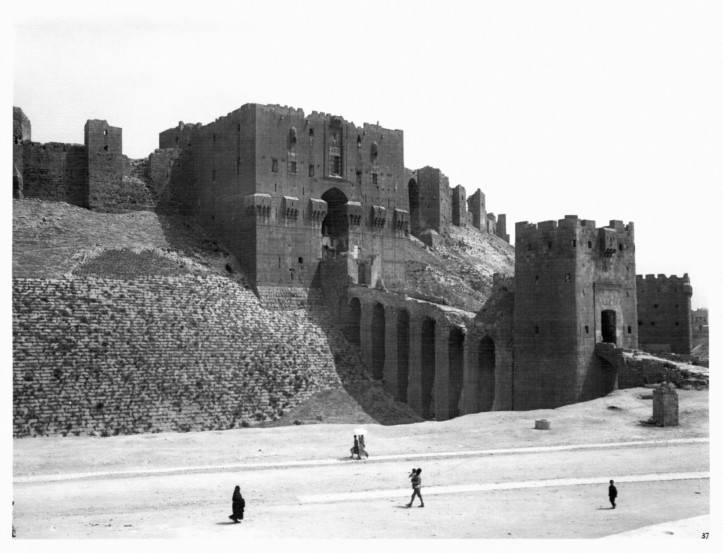

In the 12th century, a citadel emerged on the city’s central hill, swallowing up the temple of the storm god—it’s a sandstone stronghold, an example of Muslim defensive architecture. It has survived in good condition until the present day. It’s an imposing, even breathtaking landmark: in 2001, I crossed the bridge over a dry moat and climbed a wide stone rise to reach a gate with snakes carved above it. They were meant to deter enemies. Inside, behind the walls, there’s a city within a city, where—under various rulers—artisans, artists, soldiers, and servants used to live. Today I no longer remember the details—just that the fortress was full of families and tourists, like a public square on which it’s pleasant to spend the whole day together. And that I got dizzy when I looked down at the city: Aleppo was spreading into infinity, like a patchwork of tiny sand-colored scraps disappearing somewhere into the dust of the desert where we traveled later in a battered Mercedes. During the whole trip, its driver held a lit cigarette in one hand and a glass of tea in the other.

Before the war, the old town surrounding the citadel—full of bustle, detail, and sounds—was a paragon of good coexistence. Modern urbanists write and dream about a place like this—a city of narrow streets, close relationships, services available within walking distance; a space of communal continuity and exchange, and the sharing of resources. Nothing new under the sun. The Muslims turned out to be masters of architecture which connects and facilitates encounters. In the Middle Ages, Aleppo’s temple of Jupiter was replaced by the Great Mosque built by rulers from the Umayyad dynasty, featuring an almost 150-feet tall square minaret. Reconstructed over and over again, it came into being between the fifth and eleventh century and was a unique example of Arab art and Aleppian craft, as well as of the city’s multilayered history. Within the tower there was a stone spiral staircase, and the walls were covered with reliefs—the more elaborate the higher you climbed. Inscriptions mentioned subsequent rulers and patrons, from the Seljuks to the Mamluks. The minaret was completely destroyed in April 2013, when the fighting in the city had been going on for almost a year. Both sides of the conflict blamed each other for the monument’s destruction.

Other parts of the Great Mosque have also been subject to vast damage; in my memory, it is still a sun-drenched courtyard with a patterned floor, surrounded by porticoes with conical vaults. I remember sitting with my back against a column, ignoring the sweat trickling down my head. I’m wearing a black niqab, which one of the women at the entrance fastened tightly under my chin. We’ve been here for a few hours, delighted with the beauty and harmony of the building, charmed by the gentle coexistence it encourages. I remember the feeling that I could stay there forever. People come to pray, but it’s prayer typical for Muslims: it is more about spending time in the house of Allah; about lounging, talking, lazily keeping an eye on the children running around the stone floor, unhurriedly reaching into a pot of aromatic rice with a spoon, dozing. It’s about being. For centuries, the Umayyad mosques in Aleppo and Damascus were ideal temples for the whole Muslim world. I would later visit many of them and realize that these two remained unparalleled.

The Muslim everyday life and Aleppo’s location as a key point of silk routes (their land and sea branches) allowed the city to flourish. A three-hundred-year stretch of prosperity started in the 16th century once it became part of the Ottoman Empire: after Constantinople and Cairo, it was the third most important city in the massive empire which, at its peak, encompassed the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Europe. Aleppo attracted pilgrims on their way to Mecca and tradesmen—it became a meeting place, as well as a center for the exchange and production of goods. On its outskirts, workshops were built; in the center, more souks, but also caravanserais—a combination of inn, warehouse, and trade office. They were vast building complexes, usually consisting of a large courtyard, a workshop, storage space, accommodation, and eating areas. From the 15th century onwards, they also housed the consulates of the trade powers of the time: Venice, England, France, and the Netherlands. Each of these countries signed so-called “acts of capitulation”—documents granting their signatories numerous privileges, including a guarantee that their trade interests would be protected, accommodation, tax reliefs and exemptions from Islamic law regarding the social sphere. Caravanserais were both separated off by gates that would close at night, and connected to the rest of the city’s dense structure with mezzanines. Different parts of souks were also similarly protected and connected. Gates could be closed to secure precious wares, but during the day they would become centers of exchange, wide open to various interests and perspectives.

Open up, Hammam!

The city and its architecture provided both contact and a sense of safety. Islamic buildings and spaces played a huge part in this. The key triad of hammam-mosque-souk was opened by the city baths. Ablutions were necessary before a Muslim could pray at the mosque and enter the world of trade at the souk. As we would say today, hammams played the part of holistic wellbeing centers, attending to the health and hygiene of the body and mind. Hot steam baths or alternate streams of warm and cold water were applied to detoxify, relax, and cleanse, which is why the hammam was called the quiet doctor. Baths were spread all around Aleppo, often underground. Their entrances were low-key, but the interiors were lavish. The changing room had a vital function: it was a living room, a crossroads, a market square. For women it long remained the only place for unrestrained interaction and entertainment. Hammams would open at different times and days for men and women, although some baths were so vast that they had separate rooms for both.

In the summer of 2001, about a dozen baths are still in operation in the city. Midday, the time for women. We go to the Hammam Yalbugha near the citadel. Built in the mid-14th century, in the Mamluk era, it is considered Syria’s most beautiful. In an impressive changing room with huge windows under the massive vault, with alcoves and small chambers for privacy, an attendant helps me undress, wraps me in a coarse cotton towel, and invites me to a steam-filled corridor. The stone room is lit only with narrow beams filtering through the skylights in the domes. Through the arched door I can see other rooms and basins carved in stone, overflowing with water. Girls are stretched out along the walls. They’re very young, wearing swimsuits. The attendant, an older woman with an ample bosom and wearing a damp slip, tells me to lie down on the floor and wait in the billowing steam. From time to time, she interrupts her chat with a friend to prod my skin. Finally, using a rough mitten, she starts to rip away layers of dead cells, dust, and fatigue. She turns me from side to side and rubs. She’s not gentle; it hurts. Limp, I listen to the murmur of the water and watch the cockroaches wandering along the stone walls. Everything gleams, including the insects. After I’m heated with hot water poured over my shoulders from metal basins, brutally chilled by ice-cold streams, and wrapped in cotton again, I finally end up in the changing room with my friends. The attendants bring us tea, cigarettes, and nuts, and leave us to gossip in an alcove. I observe the beautiful Syrians who spend up to half a day at the hammam. Once they’ve had their tea and put on their tight jeans and sexy tops, they spend a lot of time applying make-up to their eyes, eyelashes, and lips. It’s only then that they cover up with a black abaya, revealing to the world only their faces with huge, riveting eyes. They stop giggling, pay the attendants a generous baksheesh (tip), and leave—silent and unapproachable once again.

The institution of the hammam started losing its significance as private bathrooms became common. But mid-20th century Aleppo still had sixty active baths. The one I visited was destroyed in 2013. It is being renovated by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture—an organization founded by a Shiite imam from a ducal family. It is also leading the partial reconstruction of some bazaars, like the souk Al-Saqatiya which originally housed butchers. It took eight months and cost $400,000 to reconstruct around one hundred yards of the souk’s alleyway. According to various estimates, restoring Aleppo would cost tens of billions of dollars. Nobody has that money—certainly not the Syrian government. Assad’s regime is still fighting the rebels, but far away from Aleppo now. There are international sanctions against the country; the West won’t commit resources to it even for a noble cause. Thus small rebuilding projects paid for by Muslim foundations are the only light in a long tunnel.

After Bombs Come Eggplants

At the beginning of the 21st century, the people of Aleppo have time. A conversation is worth more to them than money. Our every journey through the scorching city attracts a cordon of companions. They ask for mementoes from Poland, ply us with questions about our fathers, about religion. We get similar questions from jewelry sellers at the eight-mile-long souk Al-Madina. I like the look of a heavy silver and turquoise necklace. But although the merchants are chivalrous to all four of us (the shop boys immediately bring stools and conjure up little glasses of strong tea), none of them thinks of addressing me or even looking at me. All the conversation is directed towards my red-haired friend: a man. After they exchange pleasantries, inquire after each other’s families, talk about the reason for our visit and further plans, equally unhurried negotiations can begin. Once banknotes finally change hands and the necklace is wrapped, the stall owner congratulates my companion on his three beautiful wives. Then he takes the liberty of joking: “But you know, my friend, having three wives is no problem. The real problem is three mothers-in-law!” We part among laughter and the clink of empty glasses. I still have the necklace.

During the war, the souks of old Aleppo and its historic part became a bastion for the rebels and those civilians who were the most resilient or unable to escape. A quarter of a million people were estimated to have been stuck there. After 2015—with Russia’s military support—the old town suffered daily attacks with barrel bombs filled with shrapnel, as well as cluster bombs which release many (even up to a few hundred) smaller charges. Schools, hospitals, and power hubs were intentionally destroyed. The last year of existence under siege meant no food, no electricity, no water or medicine. The remaining civilians risked their lives waiting days in the line for bread, a few hundred times more expensive than before the war. It is estimated that up to three hundred thousand people died during the war in Aleppo alone. When Bashar al-Assad’s government announced that it had taken full control of the city, the historical quarter was ruined. The rebels also contributed to its destruction as they carved through the walls of houses and dead ends, dug tunnels under souks and caravanserais, filled them with explosives and blew them up, killing Syrian soldiers. This is, for example, how the impressive Carlton Hotel and the main police station were destroyed. For four years, fighting took place on hitherto quiet backyards with fountains, on courtyards that used to be full of greenery, on market alleyways stripped of beautiful objects. Sophisticated architecture became a deadly labyrinth in which enemies separated by low walls threw insults and grenades at each other, the way neighbors used to with jokes and kind words.

Although fighting continues in many areas in Syria, Aleppo’s survival gene, extolled by historians, has surfaced again. Small islands of the old friendliness are slowly blossoming. Eggplant stands and cafés are returning to the streets. Syrians are sitting down to talk and trade. A new generation of stonemasons is learning the craft, unearthing from beneath the rubble intact lumps of sandstone to recreate houses and alleyways, which one day will perhaps be alive with trust again.

Translated from the Polish by Marta Dziurosz