In her book “Lonesome as a Swede”, Katarzyna Tubylewicz explores the Swedish concept of ‘solitude’ and how it differs from ‘loneliness’. In the excerpt below, Tubylewicz talks with David Thurfjell – Professor of Religious Studies at Södertörns högskola in Stockholm – about the intersection of aloneness and nature in Swedish society.

In German there exists the word Waldeseinsamkeit, which describes a particular feeling of solitude or aloneness experienced only in forests. In Swedish, as well as in many other languages including Polish and English, there is no such word. Yet Sweden is precisely the country where being alone in the forest or some other place in the bosom of Nature is a state that people long for, seek and celebrate.

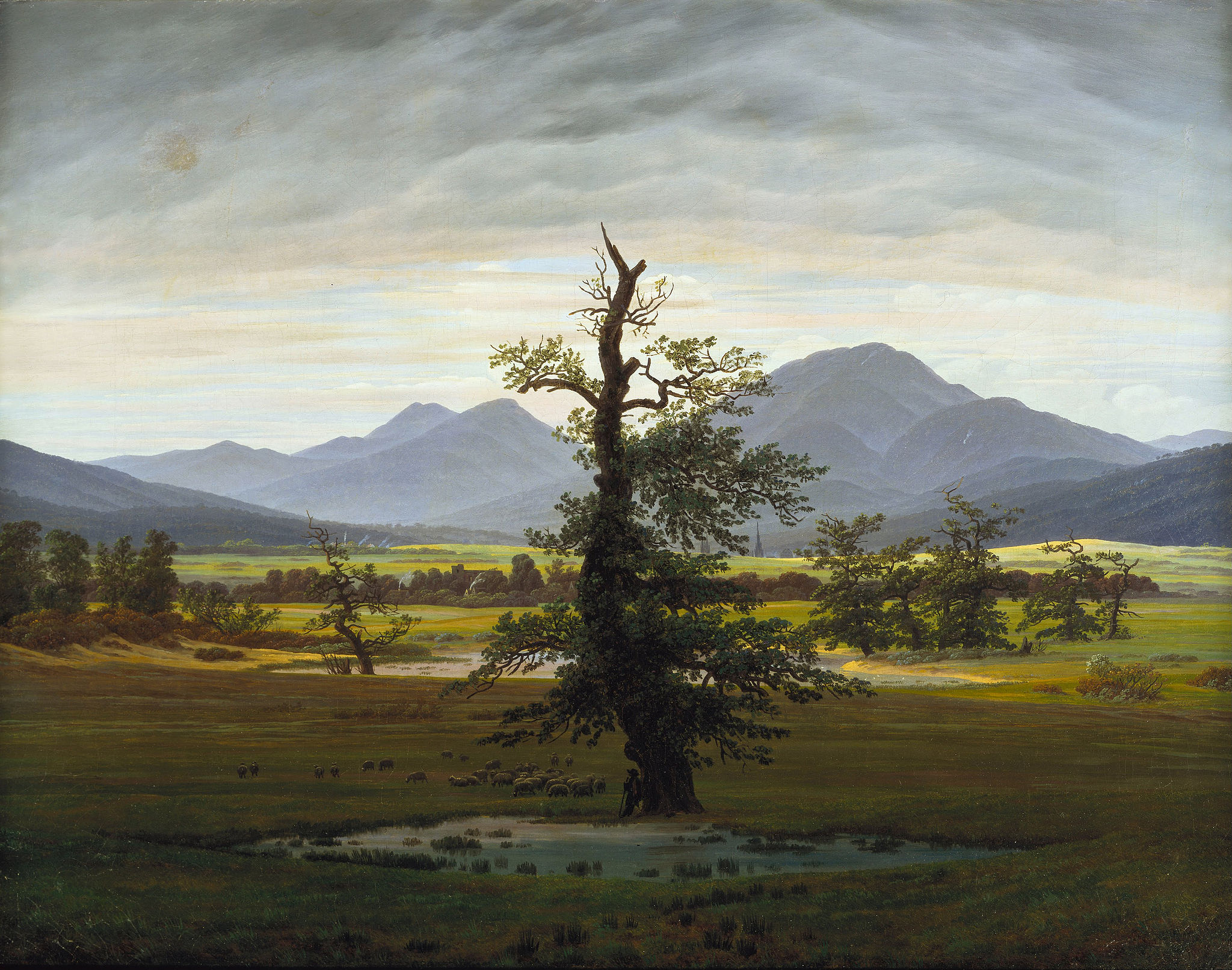

It is in the bosom of Nature that Swedes discover themselves. It is Nature that gives them the spiritual experiences they do not get in church. Sweden is a country whose inhabitants are sceptically inclined towards all institutionalised religions and usually define themselves as agnostic. Of course, in such a multicultural country, there is room also for religiosity, even zealous forms of it, but at the peripheries of mainstream social life. Meanwhile it is possible to detect elements of Protestant morality in the mindsets and actions of secular native Swedes, although its presence is not entirely conscious or connected with spirituality. Places of metaphysical searching are therefore not chapels but the skerries of the Stockholm or Gothenburg archipelagos, the flat rock above a lake beside a house, the dense forest which can be found everywhere in this country, the boundless meadows of Öland or Österlen.

David Thurfjell, Professor of Religious Studies at Södertörns högskola in Stockholm, recently returned from the Sarek National Park in Swedish Lapland. A park so large that a minimum of two weeks should be put aside in order to get to know it, and where it is impossible to move around without a map and compass. A boundless virgin space in which you can feel a connection with something great, as David Thurfjell explains in our conversation: ‘It’s a landscape in which there is no trace of human existence, only endless wild nature imparting a sense of eternity and the conviction that I too have eternity within me. In the encounter with this world, you become yourself again, your real self.’

Thurfjell has recently published a book entitled Forest People: How Nature Became the Religion of the Swedes (Granskogfolk: hur nature blev svenskarnas religion, Norstedts, 2020). This is how he defines its reader in the opening chapter: ‘You are not religious, but when you spend time alone in the bosom of Nature, you feel you are making contact with a certain something, maybe not God, not literally Him, but something greater than everyday life, more profound and more powerful, something that involves the meaning of existence and its boundaries’.

Is it true that Swedes are the loneliest people in the world?

The loneliest island in the world is Kungsholmen in the centre of Stockholm. It has more single households than anywhere else in the country. I believe there is a huge difference between unwanted loneliness and freely chosen aloneness. Swedes are certainly characterised by a large dose of individual autonomy. We do not like reciprocal obligations, debts arising from the fact that someone else has helped us. This is well illustrated by an anecdote from my own life. A typically Swedish one. When I was last in India, ice-creams had to bought in one place in exchange for coupons. Each coupon cost one rupee, that is next to nothing. I forgot to take my coupons from the hotel room but wanted to buy ice-creams for the children. I therefore asked a German, who was working there, if I could buy three coupons from him for three rupees. He replied: ‘But I will give you them’. Three rupees was really no sum at all, yet I felt that I would prefer to buy those coupons, because I didn’t wish to feel the burden of gratitude and indebtedness. And what would happen were I to come for ice-cream the next day and again forget the coupons? Am I to be indebted for a second time? I prefer to pay. I don’t want reciprocal obligations because they’ll become a sort of burden to me. Our conversation was overheard by an American, evidently critical towards Sweden. ‘That’s what happens when you live in a too highly-developed welfare state,’ he said contemptuously. ‘You pay off all your debts.’

And it’s true. In Sweden, it’s not even worth trying to hitchhike. People behind the wheel look at a hitchhiker and think: ‘I’m paying nearly sixty per cent in tax, so I’ve already done my bit. There are buses.’

Yet Swedes also show a lot of solidarity towards others. At the height of the refugee crisis, a whole army of volunteers became involved in helping newly arrived migrants! People took young men from Afghanistan, families from Syria, into their own homes…

That’s all true, but at the same time, people avoid solidarity on the level of contacts with select individuals, the type of solidarity whose manifestation suggests the creation of relationships, the building of reciprocal expectations…

Your interviewees escape into the forest to avoid human interdependency, in search of silence of which there is plenty in Sweden, including in cities.

Yes, silence is something normal in Nordic cultures. It also includes reticence in expressing feelings. Do you know that until quite recently, telling your children that you love them was not so common in Sweden? Fathers of my generation tell their kids all the time that they love them, I do it constantly. Instead, our own parents, born in the 1940s, were not so keen to do so. I remember when my cousin got married and her Dad had to make a formal speech. He thought about what he should say and asked my advice. I told him that he can say what he likes, but that he must articulate clearly how much he loves his daughter. He reacted to this with terror: ‘No! I could never say that!’ In the end, the speech went as follows: ‘Dear Åso, you are a person popular with many, and I too belong to this group’. My Dad never told me that he loved me, but once, during a great life crisis when he learned he was terminally ill, he said with tears in his eyes: ‘We love each other’. Meanwhile my Mum manages to say: I love you in English. Swedes often do this; they go into English when they wish to create distance or feel embarrassed. Returning to the culture of silence, many of my interviewees said that they stop talking on entering the forest, even in the company of other people. I have noticed that I do it myself. It’s a bit like entering a church.

You claim that the majority of Swedes enjoy a special affinity with Nature, and that this is one of the reasons why they prefer to spend their holidays in a cottage in the forest or by a lake, rather than in warmer climes.

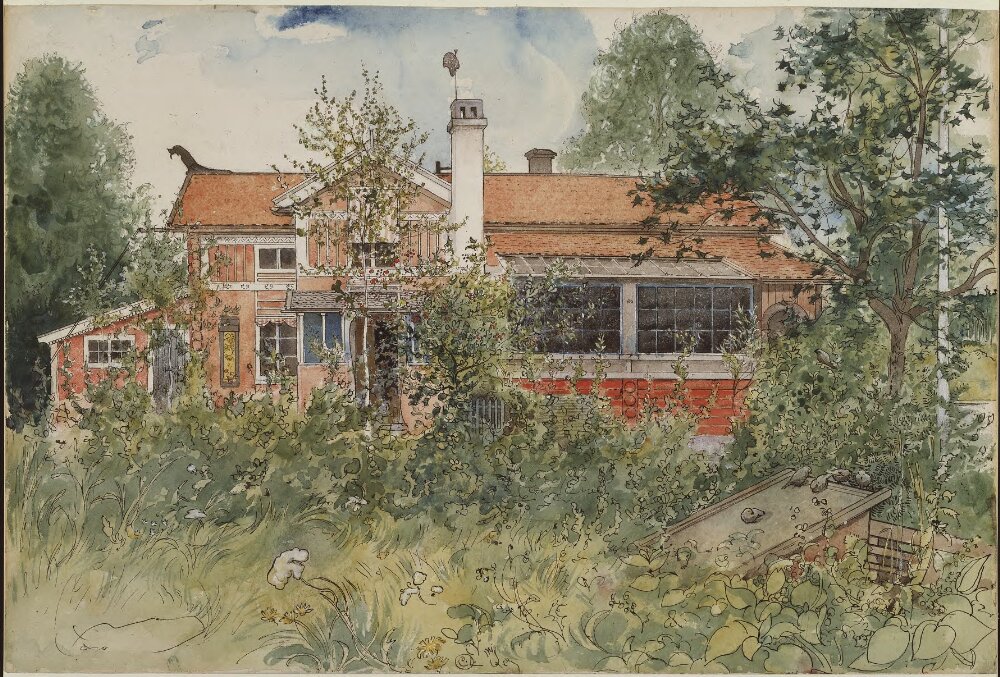

You have to remember that Sweden has only recently become a country where the majority of people live in cities. This is something new in our culture. Until recently we were all still peasants. When people are suddenly separated from Nature, they begin to lead modern lives, and the fact of when the sun rises or sets ceases to have any significance for their work; therefore, entirely new features get ascribed to Nature. In Sweden, the idea of Nature is associated with free time, with freedom. Going on holiday to the countryside is not only a change of scene, but also a sentimental return to former times. On holiday, people eat traditional foods — herring, potatoes, strawberries. People dress differently. They might organise a crayfish feast, or sing time-honoured refrains when drinking alcohol. Go for a run barefoot. You can live quite differently from how you would in a city. Nature becomes a place for realising romantic dreams, a happy place.

Maybe this idealisation of peasant life is also connected with the fact that Swedish peasants were always free; they did not know serfdom. Poland is also a peasant society, but in Poland, the countryside is associated with something worse than the city, something more primitive. No doubt this has its roots in the centuries-old abasement of peasants by serfdom, and maybe this is also the origin of Poles’ greater indifference towards Nature.

There are many theories as to where Swedish individualism hails from, and one of them does link it precisely to the situation of Swedish peasants, with their freedom and independence. But it’s important to add that in Sweden, any romantic aspect is attributed to the lives of rich peasants, not poor farm labourers.

Nature is also, as you have already mentioned, a space of new spirituality. The contemporary equivalent of church to which people go alone, however, and not in a group.

This is very interesting, because most of my interviewees stated that when walking on their own in the forest, they do not feel alone. They experience a feeling of belonging. Of being close to something good. They may feel lonely in a crowd, in the city, where they are troubled by anxieties such as fear of death. When they enter the forest alone, they cease to be lonely. This is no doubt connected with our cultural heritage. In the first known written account of Sweden, which may be found among the two-thousand-year-old notes of the Roman historian Tacitus, the Swedes are mentioned as one of the northern Germanic tribes, and said to be a tribe that prays to the forest. Also, members of this tribe do not wish their houses to be too close together like they are in Rome. They wish to have wild Nature surrounding their homesteads. In other words, already two thousand years ago, our culture included introvert, slightly autistic features and already then, we loved Nature. Contemporary Swedes, when describing their attitude to Nature, often say that it heals their souls. It diminishes their fear of loneliness and death. It is something real, and provides a contrast to the lack of authenticity they perceive in everyday life.

Is loneliness less of a taboo in Sweden than in other countries?

It is certainly the case that should a young person start living with a boyfriend or girlfriend immediately after leaving home, this would be seen as strange. Young people are expected to live on their own for a few years, fortify themselves, get to know themselves. Certainly, a cult of aloneness or solitude also exists in our culture, which people choose for themselves. The cult of an expedition or adventure undertaken alone. But unwanted aloneness is associated, of course, with shame. Especially the lack of a partner and sexual loneliness can carry something of a stigma. On the hand, being a single parent, for example, is nothing odd.

You are a scholar of religion. Your previous book was also about Sweden and was entitled The Godless Nation (Det gudlösa folket: de postkristna svenskarna och religionen, Norstedts, 2019). Does their high level of secularisation somehow deepen Swedes’ sense of loneliness? Does it mean they feel more existentially alone than in the times when they believed? Or do they simply miss going to church and the people once met there?

It is rather that Swedes regard themselves as highly secularised and are perceived as such by others, yet in reality they are very loyal to the Church of Sweden. Lutheranism is not and never was a particularly spiritual form of religion. For Luther, the believer had to be a loyal citizen. God is best served when you are a cog in the social machine; rituals are unimportant. Today, only two percent of Swedes attend church, while a hundred years ago, it was five percent, although all citizens of the country were at the same time members of the church. In Lutheranism, you go to church to be baptised and to be buried. Therefore, Sweden is a country that for a long time had little religious religion, while secular Swedes are still in many ways the perfect Lutherans. They have Christian forenames, pay taxes to the Church, benefit from the help of a pastor when organising a wedding or funeral, are extremely loyal towards authority. In Sweden, there is an exceptionally high level of trust in the state, which also has its roots in Lutheranism. The need for spirituality is realised elsewhere. In the bosom of Nature, in other Churches, for example the Pentecostalists, through yoga, through exoteric interests.

All right. So, Swedes are individualists, they like social solidarity but solidarity that doesn’t bind them to other individuals; they do not seek intimacy in religion; they feel least alone on a solitary walk in the forest. ‘Separate’ people to the nth degree. And yet at the same time, Swedes very much like to chat to one another, are very unwilling to get involved in conflicts or stand out from the crowd, they eagerly sign up to trade unions. How do you understand this?

Collective mentality as well as strong social control also dominate in Sweden. We want to be individualists yet feel strong loyalty towards the herd. During the current pandemic, we maintain social distance out of loyalty to the Public Health Agency and the decisions of Swedish epidemiologists. I have a doctoral student who is writing about religion and autism. She is proving to us that all people have tremendous social needs, even those who are totally incapable of social interaction. Autistic individuals are not capable of intimacy, but they seek it nevertheless. I believe that we, the inhabitants of Sweden, have no less a need of social contact than other nations, but we live in a culture which predisposes us to other types of reaction. People employ those methods for gaining acceptance that their culture has taught them. If, therefore, in order to be part of the group, it is necessary to preserve a certain distance, if maintaining reserve is the best means of gaining acceptance and love, then people will adjust to precisely this method. If you are an Italian man, you know you have to kiss everyone, slap them on the back and talk loudly, in order to be close to them. And so that’s how you behave. In Sweden, the means to be close is to keep your distance. This is our method for building ties between people. Distance. It’s a bit sad.

Or maybe some comfort, if distance is only another form of searching for intimacy?

This is an excerpt from Katarzyna Tubylewicz’s book “Samotny jak Szwed” [Lonesome as a Swede] published in Poland in February 2021 by Wielka Litera.

Translated from the Polish by Ursula Phillips