They helped artists who were trying to find a visible form for supernatural phenomena. They allowed for the introduction of emotions and fantasy into a rational space. They inspired the imagination. It seems that lying on your back and staring into the clouds can also help you to understand painting.

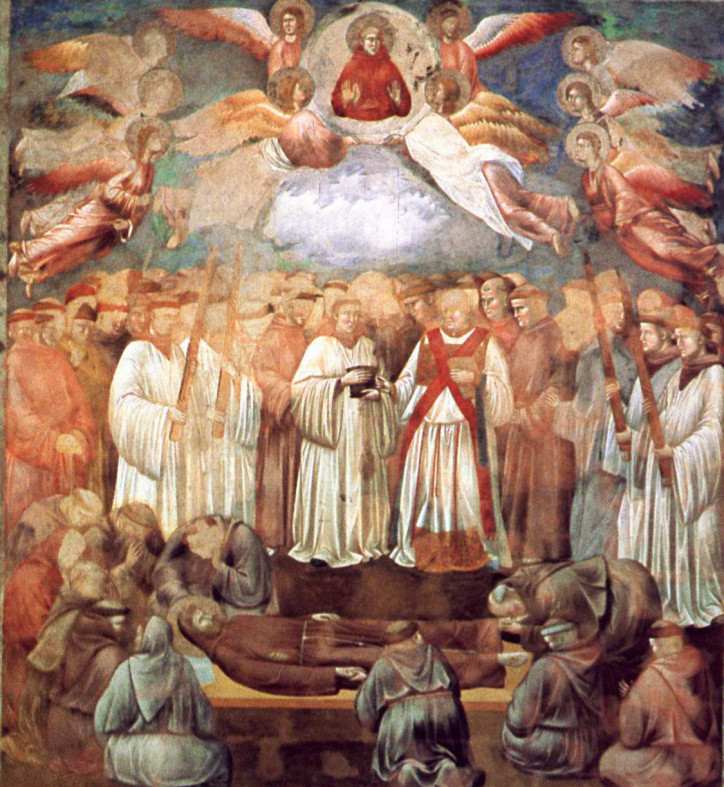

Art historian Chiara Frugoni has studied Giotto’s Franciscan series in the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi for a few dozen years. But it was only in 2011, during the renovation of the frescoes, that she climbed the scaffolding. She suddenly noticed a devil-shaped cloud in the scene of Saint Francis’s death. A profile with a hook nose and a sinister smile is quite distinct. But it was missed earlier even by the experts; we usually see things that we expect to see… A demon is fighting against angels and obstructs a soul’s journey to heaven. Perhaps the Satanic face in the clouds is a mischievous joke of the medieval artist. Up until now, it was thought that Andrea Mantegna was the first who hid figures in the clouds in the second half of the 15th century. In the St. Sebastian of Vienna, he placed a cloudy rider in the left upper corner. Armed with a sickle to cut through the cloud, he was sometimes identified with the Roman god Saturn; the symbol of the devastating power of time.

Mantegna repeated a similar trick four decades later in The Triumph of the Virtues, painted for Isabella d’Este. In this painting, the faces of the Virtues emerge from fluffy clouds.

In a natural halo

In Early Christian art, heaven was interpreted in the sacral context. Up until the end of the Middle Ages, it was shown as a smooth, golden surface. This gorgeous screen signalled God’s presence and ruled out all earthly connotations. However, the Gospel itself seems to encourage including clouds. “Thou hast said: nevertheless I say unto you, Hereafter shall ye see the Son of man sitting on the right hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven,” Christ says in Matthew (26:64). A cloud allowed for a connection between heaven and Earth, between what is real and what is supernatural. In the mosaic in the nave of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, God’s hand emerges from red clouds. Then, in the 12th-century decorations in the Basilica of Saint Clement, Christ’s bust and the figures of the four Evangelists are shown on layers of light clouds. While painting Founding of Santa Maria Maggiore, the 15th-century artist Masolino wanted to highlight the divine inspiration of this undertaking. Above, on a golden background in a rainbow mandorla, Jesus and Mary bless the site. Both spheres, earthly and heavenly, are divided by an oblong, navy-blue cloud and a formation of little clouds, not very realistic, but highly decorative.

From the 12th century onwards, blue became the colour of divinity, almost on par with gold. It was equated with divine light, and that was why atmospheric expanses began appearing as the background of religious paintings. They formed a set for religious scenes, now taking place not in an abstract, symbolic realm, but in surroundings imitating landscapes and three-dimensional space. The blue background is no longer flat and purely symbolic, but starts looking like a real sky, dependant on the whims of the weather. In the background of Jan van Eyck’s Crucifixion, there are four types of clouds: cumulus, altocumulus lenticularis, cirrus uncinus and cirrocumulus lacunosus. The American meteorologist Stanley Gedzelman even suggested that such an approach is in line with descriptions in the gospels, according to which darkness surrounded the Earth during the Passion of Christ and then (according to Matthew, 27:51) “the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom”. Incidentally, Van Eyck shows a sudden bright interval after the recent passing of a cold front.

In 15th-century Italian and Flemish painting, a new feeling of space was forming simultaneously. In the North, it mainly came from the observation and perception of light, while the Italians wanted to underpin their impressions with a mathematical theory of perspective. It was introduced by Brunelleschi, described by Alberti, and his thought was further developed (and masterly implemented in painterly practice) by Piero della Francesca. But there is one element of the landscape that can’t be captured in a rigorous way according to the rules of perspective: the constantly moving, changing sky. That was why Brunelleschi, while painting his demonstration of perspective – a square in an ideal, Renaissance town – replaced the sky with a polished, silver surface in the background.

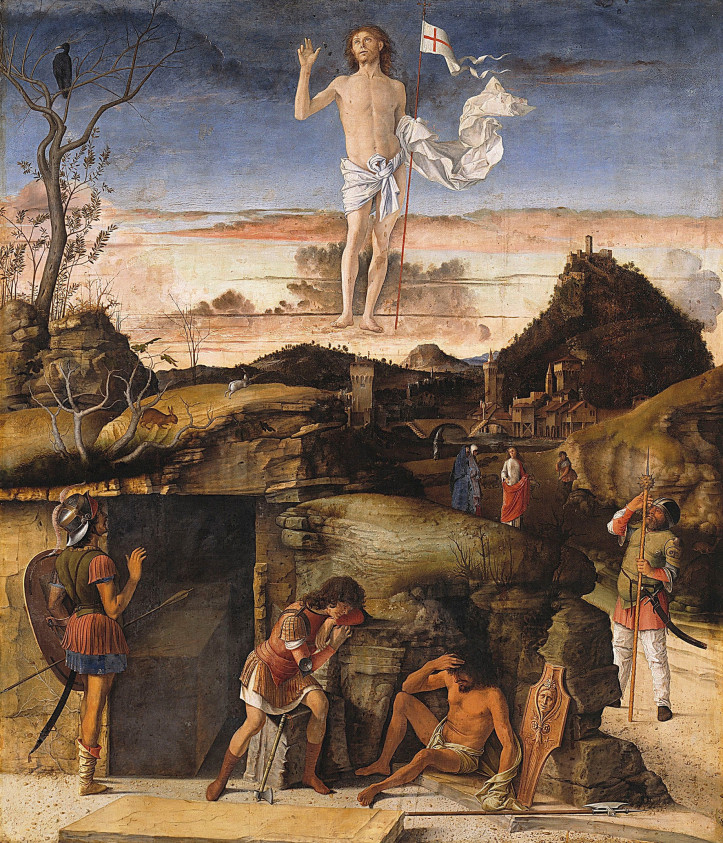

But there were also artists who could appreciate capricious clouds. As art historian Hubert Damisch notes, a misshapen, sloppy cloud that cannot be distinguished by a contour allowed for introducing fantastical, supernatural phenomena into the rational space divided by a perspective grid. Venetian Giovanni Bellini was a real poet of landscape. In his religious scenes, trees, rocks and sunsets are as important as the protagonists. In Resurrection of Christ, the sky with bloody clouds flowing through it is a framework for the miracle.

The spectacle of nature amazed and enchanted this master, no doubt causing mystic ecstasy. That’s why small pink clouds on an intensely blue background create ‘compassionate’ scenery for the Agony in the Garden. In St. Francis in the Desert, the ‘desert’, with a donkey and a heron, as well as the gentle landscape with soft, white clouds, are no less important than the saint in prayer. Art historians suspect that Bellini showed the moment of bestowing the stigmata, but he left out traditional accessories: a chapel and a seraphim with a cross. A golden light was enough to show the miracle. In the early Transfiguration of Christ from the Museo Correr in Venice, Mount Tabor is flooded with light. Bellini left out the symbolic diagonal rays, but the ring of light and scattered clouds create a kind of natural halo above Christ’s head.

The angelic condensation of air

Clouds came to the rescue of artists who attempted to express supernatural phenomena in a visible form. 12th-century theologian Peter Lombard, citing Saint Augustin, said that angels have bodies that can be seen by those in a state of special grace. Thomas Aquinus stressed that spiritual beings are bodiless, but can materialize if need be, mainly as a result of the thickening of air. In his opinion, saints and angels appear in a similar way when clouds gather: air condenses in the moment of a vision, creating a figure similar to earthly bodies. This is how angels manifest themselves. On this theological basis, Renaissance artists created “putti out of clouds”. Cloudy little angels were the intermediaries between the classical and Christian tradition, but also between Earth and heaven. Saint Thomas’s theories were carefully studied by Filippino Lippi and his Dominican patrons in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. In the frescoes decorating the Carafa Chapel, four sibyls sit on flattened, grey clouds with the heads and bodies of little angels emerging from them. On the vault of the Strozzi Chapel in Florence, Lippi also painted prophets on a cloudy eiderdown with small angels emerging from it.

This painterly concept reached other Italian schools: Mantegna surely borrowed it from Lippi, and then Giorgione and Titian from him. In Giorgione’s Adoration of the Shepherds, the pink heads of little angels are half transparent, as if the process of materializing was stopped midway. In Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin, the crowd of golden faces emerges from a luminous garland. In Titian’s secular paintings, sensitively-pictured atmospheric skies are not just a background, but also create the poetic mood of the painting. In Sacred and Profane Love, the sky stratifies into purple, yellow and blue strips with light, white clouds floating against them. In The Bacchanal of the Andrians, the scene of pleasure and debauchery is accompanied by a gorgeous, exuberant sky; fleecy clouds, as if lit from inside, flow against intense, almost violet blue. Yet according to Gedzelman, it was Titian’s fault that whole generations of painters chose an easy way when painting the sky. The scholar was irritated by the layers of altocumuli with a purple edge that Titian always painted when he wanted to suggest dusk or dawn, like in the scene with the repenting Mary Magdalene.

Unearthly scale

Pieter Bruegel’s skies look completely different. This great Fleming didn’t search the landscape for a lyrical concord with religious or mythological scenes. He most likely painted The Hunters in the Snow influenced by one of the harshest winters in Europe – the winter of 1565. The sky is covered by green-grey clouds; frozen ponds are of the same colour. In those conditions, the light spreads evenly, with almost no shadows. On the other hand, in The Gloomy Day Bruegel showed a stormy sea and a sky enveloped in dark rainclouds – a grim landscape of early spring when man faces the relentless forces of nature.

The Italian masters of the High Renaissance valued fantasy, variety, unusual phenomena. Fogs and rainbows started appearing in their landscapes. Leonardo da Vinci advised: “To form a just idea of a storm, you must consider it attentively in its effects. When the wind blows violently over the sea or land, it removes and carries off with it every thing that is not firmly fixed to the general mass. The clouds must appear straggling and broken, carried according to the direction and the force of the wind, and blended with clouds of dust raised from the sandy shore. […] Let the clouds appear as driven by tempestuous winds against the summits of lofty mountains, enveloping those mountains, and breaking and recoiling with redoubled force, like waves against a rocky shore. The air should be rendered awfully dark, by the mist, dust, and thick clouds.” The author of Mona Lisa also described a flood – a deluge of water coloured with “the fire kindled by the thunder-bolts by which the clouds were rent and shattered; and whose flashes revealed the broad waters of the inundated valleys, above which was seen the verdure of the bending tree tops.” Leonardo da Vinci thought that painterly fantasy should enrich his observation. In his late drawings of a deluge, he represented a dramatic landscape with wind-chasing clouds and big waves. The artist not only exaggerated, but invented events of ‘unearthly’ Biblical scale. He also chose from nature what was spectacular. One time he made a note of an unusual atmospheric occurrence: “I have already been to see a great variety (of atmospheric effects). And lately over Milan towards Lago Maggiore I saw a cloud in the form of an immense mountain full of rifts of glowing light, because the rays of the sun, which was already close to the horizon and red, tinged the cloud with its own hue. And this cloud attracted to it all the little clouds that were near while the large one did not move from its place; thus it retained on its summit the reflection of the sunlight till an hour and a half after sunset, so immensely large was it; and about two hours after sunset such a violent wind arose, that it was really tremendous and unheard of.” Leonardo also read ancient thinkers, such as Pliny the Elder and Lucretius, who were of the opinion that watching clouds and other irregular shapes stimulates the imagination. Supposedly Piero di Cosimo adhered scrupulously to their advice and studied clouds and wet stains on the walls in search of inspiration.

A real master of the cloudy spectacle, fantastical fog and vapour occurrences was Correggio. His frescoes in the cupola of Parma Cathedral are like from a dream or a fantasy. This time it wasn’t about deceptive illusion, but about a charming vision. Grey clouds are like airbags for the crowd of prophets and saints accompanying the assumption of the Virgin Mary. As Hubert Damisch said: “Correggio was the first to achieve that end by exploiting every part of his art and using his talent solely ‘for the satisfaction of his heart, and according to his own sensations’.” In the Parma cupola, he highlighted the sudden upwards movement; the figures chased by the wind float towards the heavens. A cloud is among this painter’s most basic means of expression. It is the seat for Madonna, or a feathery basis for playful little angels. But Correggio also clearly enjoyed painting a cloud over Danae’s bed: it is Zeus impregnating this woman in the form of golden rain. And the scene where the ruler of Olympus, in the form of a cloud, makes love with Io is the Parma master’s masterpiece. Zeus’s face barely emerges from the grey billow and the woman – being entered in such an immaterial, foggy way by a god – is clearly ecstatic.

A game of chance that inspires inventiveness

Despite all the changes in landscape painting, the medieval conviction that an artist should not focus on ‘incidents’ of nature but express what is ideal and universal remained to some point in effect up until the 19th century. As was noted by Ernst Gombrich, when this metaphysical belief became unsettled, painters began rebelling against academic rules, preferring to draw from their own experiences. This ambivalent attitude to tradition marked John Constable’s thinking, probably the biggest painter of clouds in the history of art. Supposedly he used to say that when working in the open air, he tried to forget ever seeing any paintings. But as Gombrich rightly notes, an untainted approach is not the same as repressing paintings from one’s memory. Constable was filled with respect for painterly tradition and at the same time worried about mannerisms and slavish imitation. His dream was to bend down over every little flower, like Rembrandt, but give priority to dramatic and noble natural phenomena. In his letter to Archbishop Fisher, Constable explained how important painting the sky was to him: “I have often been advised to consider my Sky – as ‘White Sheet drawn behind the Objects’. Certainly if the Sky is obtrusive – (as mine are) it is bad, but if they are evaded (as mine are not) it is worse, they must and always shall with me make an effectual part of the composition. It will be difficult to name a class in Landscape, in which the sky is not ‘key note’, the standard of ‘Scale’ and the chief ‘Organ of sentiment’.” Constable struggled with the sky, which is the source of light in nature and in composition, but should not dominate it. As the painter promised: “My skies have not been neglected though they often failed in execution – and often no doubt from over anxiety about them – which alone will destroy that easy appearance which nature always has – in all her movements.”

Surely that was why the English master studied illustration in the 1785 A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape by Alexander Cozens. This theoretician suggested sketching from nature and not following old masters. It was more about the clever use of smudges and blots, the game of chance that can inspire inventiveness. Constable diligently copied Cozens’s exemplary skies: bright, with delicate streaks or just before a storm, covered in dark clouds. Those patterns didn’t substitute observation, but the categorization helped organize the impressions more. Constable knew the works of his contemporary, Luke Howard, who was the first to divide clouds into cumulus (from a Latin term meaning ‘heap’), cirrus (because they look like a lock of hair), rainy nimbostratus and stratus, and layered clouds. As Goethe said, this English scientist’s achievement was “bestowing form on the formless”. Constable left hundreds of small studies of clouds with meteorological conditions noted on their backs. Neither his scientific passion nor his interest in the art of his predecessors prevented him from painting the most realistic clouds in the history of painting.

The truth of impression

Constable admired William Turner, whom he valued for his modernity and emotional power. But he found the blurry glows and blazes of colour in Turner’s landscapes ambiguous and sometimes just plain opaque, because Turner gave himself a completely different assignment to Constable, who stubbornly painted moist skies above Hampstead Heath. As the biggest champion of Turner, John Ruskin, said: “The aim of the great inventive landscape painter must be to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts […]”, he must understand the “truth of Impression”. That is why – the theoretician explains – every one of Turner’s compositions is “evidently dictated by a delight in seeing only part of things rather than the whole, and in casting clouds and mist around them rather than unveiling them.” Sky painting went through the whole circle: from a sacral symbol to a subjective, sensual impression. This final approach was also not free from limitations, of which Ruskin himself was well aware: “Whereas the mediæval never painted a cloud, but with the purpose of placing an angel in it […] We have no belief that the clouds contain more than so many inches of rain or hail.”

Lying on one’s back and staring into clouds, being “in the service of clouds” described by Ruskin, can help understand painting. Keith Christiansen, curator and Chairman of the European Paintings Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, admits that he is fascinated by clouds. And what immediately escapes in the sky can be captured in a picture for centuries. As one art historian confessed, one stormy cloud hanging between two high-rises made him realize that El Greco’s View of Toledo is not a whim of mad imagination, but a work of art inspired by the actual experience of landscape. “What, then, extraordinary stranger, do you love?” asks Baudelaire in The Stranger. “I love the clouds—the clouds that pass—yonder—the marvellous clouds.”

Translated from the Polish by Anna Błasiak