The sculptor Maria Papa Rostkowska led a happy life. Maybe that’s why so few people remember who she was.

Dear readers! Like the lives of most of Poland’s best artists, the life of the “giantess” and at the same time “fashionable kitten” (as the heroine of our article was variously described) was rich in tragic events. Yet simultaneously, it was an exceptionally successful and happy life. Even so, or perhaps precisely because of this, her name remains almost completely unknown in Poland. What to do? We’ve already grown accustomed to the idea that Polish society doesn’t exactly shower its outstanding artists with love.

The artist in question, Maria Papa Rostkowska, came into our world on 4th July 1923 in Brwinów (near Warsaw), the second of four daughters born to Bolesław Baranowski and his Russian wife Nadezhda Yadushkin (it’s worth adding that an admixture of Tatar blood flowed in the mother’s veins). The Baranowskis married in 1917 in Moscow, before moving to Poland a year later. Bolesław so wanted to have a son that within the family circle, little Maria was called Maciej (a male first name). This must have left a clear trace in her psyche, as she recalled this detail even in the final years of her life. But it didn’t interfere with her happy childhood. She spent a lot of time on her grandparents’ estate in Słonim, in today’s Belarus. Some of her most beautiful memories of that time are her stories about the wonderful horse Kasztan (Chestnut), who roamed freely through the park surrounding the house, and who every day at breakfast looked in through the open window, as if he wanted to participate in the family’s life. This horse later became a frequent subject of the artist’s drawings and sculptures.

Honoured and saved

In 1935, Maria began her studies at Zofia Sierpińska’s Gymnasium in Warsaw, which she completed in June 1939. After the war broke out, she did not enrol in any school for another year, but resumed her studies in 1941 in the underground education system, initially in a biology-mathematics high school, and later in the Jastrzębski Warsaw Ladies’ Construction Drawing School. Here in June 1942, she received her secondary school diploma. Almost exactly one year later in July 1943, Maria married Ludwik Rostkowski Jr., a medical student and Alliance of Democrats activist. His father, Ludwik Rostkowski, was an outstanding eye doctor, as well as an activist in the Polish Socialist Party. He was the reason why the Rostkowski family joined the Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland, better known by its code-name Żegota. The members of the organization helped people escape from the Warsaw Ghetto. After the war, Ludwik Rostkowski was honoured with the title Righteous Among the Nations, awarded by the Yad Vashem Holocaust remembrance institute, and a portrait of Maria’s father-in-law can be found among the righteous in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

After the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising on 1st August 1944, Maria became a liaison in the People’s Army, with the code-name Katarzyna. For her actions in the Uprising, she was awarded the Virtuti Militari Cross, 5th class, 2nd degree. As the Uprising was drawing to a close, Maria, along with her mother and one sister, was captured and put on a transport leaving for Auschwitz. After the train had left the city, her husband and father-in-law – who as Red Cross volunteers were feeding refugees who had fled Warsaw – noticed her in one of the wagons. By a happy coincidence, they had an extra Red Cross armband with them, which they managed to give to her. As soon as she slipped it onto her arm, she jumped out of the train. That same evening, she was safe on a farm near Pruszków, together with both Ludwiks. Her mother and sister ended up first in Auschwitz and later in Ravensbrück. Her father was sent to Dachau. All of them managed to survive and return home.

After its liberation in 1945, Maria returned to the destroyed city of Warsaw. She found one of the few surviving buildings at Ulica Marszałkowska 18, where according to her account, “there were still bodies lying on the steps.” She stayed there in a small apartment, number 39. Soon she was joined by her husband and her parents-in-law, and – after their return from the German camps – by her parents as well. Maria, most likely influenced by her father-in-law and husband, joined the ranks of the Polish Workers’ Party (remaining a member until 1948). In December of that same year, the Rostkowskis’ first and only son came into the world, and was given the name Mikołaj Zbigniew.

Maria’s husband Ludwik was serving at the time as vice-president of the Council of Democratic Youth. It was thanks to his contacts that in 1947 Maria received a six-month fellowship from the Ministry of Culture and Art, and left for Paris. Her son remained under the care of his father and grandparents. Thanks to assistance from UNESCO, her stay in the world capital of art was extended; she finally returned to Poland only in 1950. In Paris, Maria began studying classical painting in the best possible place for this purpose: the Louvre. At the time, the studio was supervised by Professor Janusz Strzałecki, who would later play a not insignificant role in her life. Simultaneously, Maria soaked up the atmosphere of leftist engagement that was omnipresent in post-war France. She became a member of the French Communist Party, as well as the Polish United Workers’ Party. She also signed up for the Union of Polish Youth, and the Association of Polish Artists and Designers. It must be pointed out that in France at that time, such engagement by ‘well-intentioned’ artists was quite typical. All of them created what Urszula Czartoryska described as “Socialist-inspired realism”.

While still in Paris, Maria divorced Ludwik in April 1949. Just over a year later, at the beginning of June 1950, his life ended at the age of 32 in circumstances that have never been explained. Maria’s mother found him hanging in the lavatory; the door of the apartment was open wide. It is assumed that this could have been a simple execution – Ludwik was a prominent political activist, and he died during a period of strengthening Stalinist purges. Rostkowski found himself in the centre of a game for a new division of power. This is suggested by the fact that even before the ambulance was called, secret police agents appeared in the apartment, taking away all letters and documents related to his political activity. Or, on the other hand, maybe it was a suicide?

In the right place at the right time

In April 1950, Maria was accepted to the position of lecturer in Strzałecki’s studio in the PWSSP art academy in Sopot. She spent the next two years there, moving in 1952 with the professor to the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts (ASP), where she worked until 1957. During this time, Maria painted Socialist Realist paintings. They are mainly portraits of men, depicting important figures of the political and cultural life of the day, e.g. Portret Aleksandra Bardiniego [Portrait of Aleksander Bardini] (ca. 1954) and Portret przodownika pracy Gronostajskiego [Portrait of Work Leader Gronostajski] (1950). Various women also appear on her canvases: Portret młodej Ślązaczki [Portrait of a Young Silesian Woman] (1952) and Portret malarki [Portrait of the Painter] a self-portrait, presented as part of the famous exhibition during the post-Stalinist thaw Against War – Against Fascism in the Warsaw Arsenal in 1955). She also made drawings (e.g. for the Lenin Museum in Kraków and for the album The Great Proletariat, dedicated to Ludwik Waryński). But that’s not all, because in 1953 she worked on a copy of a Paolo Veronese painting for the Jerzy Zarzycki and Jerzy Jassendorfer film Uczta Baltazara [Belshazzar’s Feast]. And in 1954, together with Strzałecki, she made the decorations for the frontage of the building at No. 10, Old Town Market Square in Lublin, and the design of the ceiling of the State Council room.

In the second half of 1950, Maria’s position strengthened. In 1954, she received a diploma from the Warsaw ASP (from Professor Felicjan Szczęsny Kowarski), and lived with her son in her own two-room apartment at Ulica Piwna 42. She also had her own studio (earlier she worked as a guest in Strzałecki’s studio). She took part in various exhibitions, mainly in Poland, but also in Berlin. Even so, when in 1957 the renowned French painter Edouard Pignon – whom she had met earlier on the occasion of the Fifth World Festival of Youth and Students – arrived in Warsaw, she asked him for help to return to Paris. Pignon sent her an invitation. By the end of that year, Maria was in the city of her dreams.

Thanks to her contact with Pignon, Maria found herself “in the right place at the right time and in the right company”. In the late 1950s, the right place was on the Left Bank of the Seine, in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district, between the famous cafés Café de Flore, Le Sélect, La Coupole, and Les Deux Magots. It was in this last one that Pignon introduced her to Giuseppe Antonio Leandro Papa – better known by the pseudonym Gualtieri di San Lazzaro – who in the summer of 1958 married Maria. The witnesses were the painter Serge Poliakoff and the critic Pierre Volboudt. San Lazzaro was almost 20 years older than Maria – a Sicilian living in Paris; an art critic and publisher of the artistic periodical XXe Siècle. This elegant, actually album-quality publication printed mainly reproductions of classic works by Paris Bohemians, from Giacometti to César. It also published Mircea Eliade, Michel Butor, Eugène Ionesco and Raymond Queneau. Many people from this circle, including Joan Miró, Sonia Delaunay and Marino Marini, later became close friends of Maria.

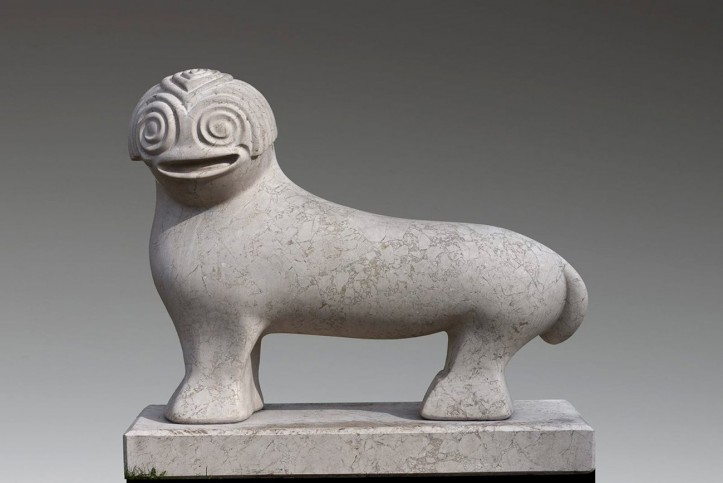

Right after the wedding, San Lazzaro took Maria to the global centre of ceramics: Albisola in Liguria, Italy. The artists in the town’s workshops included Giacomo Manzù, Karel Appel and Lucio Fontana. Encouraged by them, Maria began to make her first terracotta spatial works, inspired by human and animal heads and torsos. After returning to Paris, where the newlyweds lived in an apartment at Rue Jacob 30, Maria, initially in secrecy from her husband – who like a true Sicilian, would have been happy for her to her stay at home – rented a studio from her sculptor friend Émile Gilioli. But soon, when her work won the appreciation of their friend Lucio Fontana, as well as Miró himself, San Lazzaro began to support his wife’s art.

Maria’s following years were marked by intense sculpting work. Looking for just the right material, she experimented with bronze casts using the lost-wax technique. During this period, she created works including expressive torsos of women, sometimes described by critics as “mutilated”. The artist also took part in several group exhibitions in Paris and Albisola. In 1959, she managed to bring her son Mikołaj to Paris. In 1963, her husband bought a house for her in Boissano, Italy, along with a ceramics studio and garden. He himself lived in a specially restored small castle in Liguria, which was to supply him with the solitude he longed for.

Sea of marble

The year 1966 turned out to be a breakthrough for the new art of Maria Papa (as she became known). She had finally found the right medium. This was thanks in part to the sculptor Gigi Guadagnucci – who in the spring of that year showed her how to work in travertine using a pneumatic hammer – and the art critic Giuseppe Marchiori, who invited her to participate in the Marble Sculpture Symposium in the Carrara region. In the autumn of 1966, she began working with marble there. Her encounter with this material was a kind of artistic epiphany. “I worked for the first time in white marble […] it was like a sea that had congealed,” she told Ewa Prządka on the Polish Radio Programme II show An Evening of Conversation. “I was the crystallization of this sea, I held in my hand something living.”

In that same year, 1966, Maria cast off her old life, taking up residence in the Hotel da Filiè in Querceta di Seravezza, where she was the only woman working independently in the sculpture workshops. It’s not difficult to imagine that life in such conditions must have demanded exceptional spiritual fortitude. But with time she grew accustomed to it. Years later, after San Lazzaro’s death in 1974 (to the end, he ran XXe Siècle), Maria sold the house in Boissano, buying an old, desanctified Pandolfini family chapel on Via Vicinato in nearby Pietrasanta, where she set up her base. Slightly earlier, in 1968, her son Mikołaj had married Joëlle Ribert, a young ethnographer who with time would become very close to Maria. It was at her urging that Maria visited America (1970) and India (1979), where she became familiar with the teachings of the guru Meher Baba. Her daughter-in-law would later come to create the titles of her works.

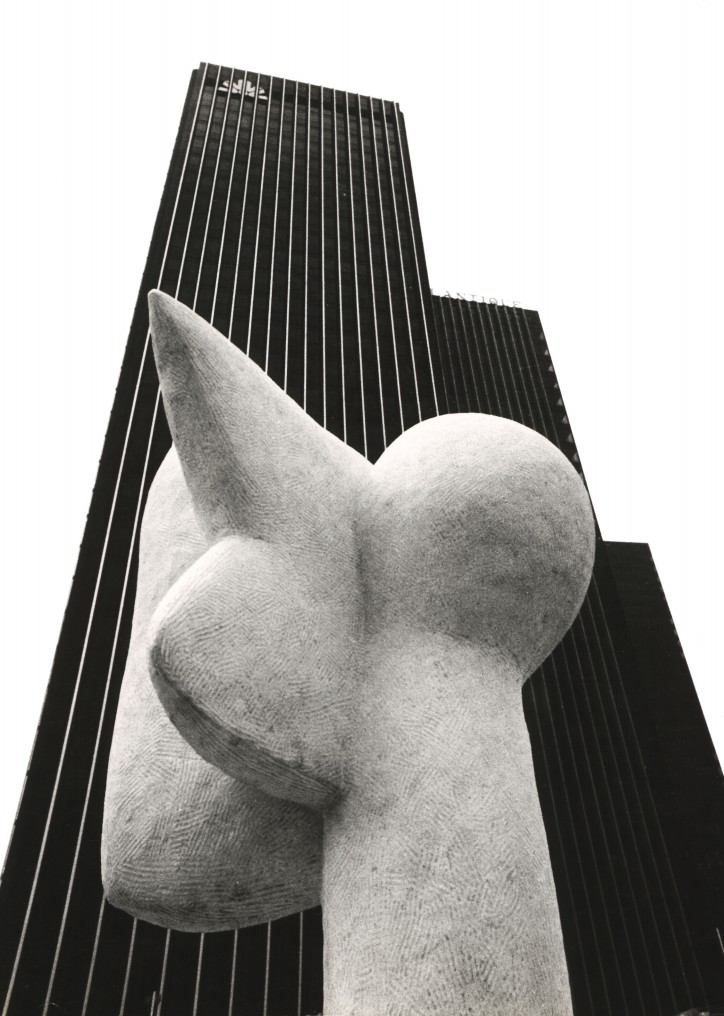

Maria Papa’s sculptures are most often classified as “organic abstraction”, referring to biomorphic forms or – as authors with a feminist orientation suggest – to “feminine archetypes”. This is also indicated by their titles: Gaja [Gaia] (1980), Jasnowłosa piękność [Light-Haired Beauty] (1975), Odaliska [Odalisque] (1973), Para [Couple] (1968), Wenus [Venus] (1985), Róża [Rose] (2003). But there is also the Warriors series. “In this sculpture there resonates the male name Maciej, which she was called, even though it turns out that she wasn’t a boy,” Agata Araszkiewicz notes, adding: “The Warriors series, as a self-commentary on Papa’s art, is a personification primarily of gender transgression, but also geographical transgression.”

Travertine warrior

Four decades passed since the moment of Maria’s first encounter with marble, but she continued working with the same unquenchable fire. Even after she suffered a stroke in 2001, she continued making sculptures, just somewhat smaller ones. She completed her last work in 2008, a few months before her death on 23rd October of that year. Over 40 years, she amassed a huge number of exhibitions, both individual and group. She showed her works mainly in the galleries of Paris and Milan, but also in Japan, and in Poland – where after an absence of 34 years, she presented her sculptures in 1991 as part of the exhibition Jesteśmy [We Are] in Warsaw’s Zachęta gallery. A larger collection of her works could also be seen in 1994 in the Warsaw gallery Ars Polona. On that occasion, Maria visited her home country for the first and only time since 1957. Her compatriots could see the next two exhibitions only after her death. In 2010, works by Maria donated to the National Museum by Joëlle and Mikołaj Rostkowski were shown in Warsaw’s Królikarnia palace, and a retrospective of her works was also shown in the Królikarnia in 2014.

The tomb in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris where Maria Papa Rostkowska rests next to Gualtieri di San Lazzaro is adorned with one of Maria’s sculptures, titled Warrior. This is the first work she made from travertine using a pneumatic hammer. She immediately took it to her husband’s gallery, where Miró happened to be. He looked the sculpture over and said: “Very good. This will be a great future for you.”

This article is part of the “Libera selects…” series on Polish artists.

Translated by Nathaniel Espino