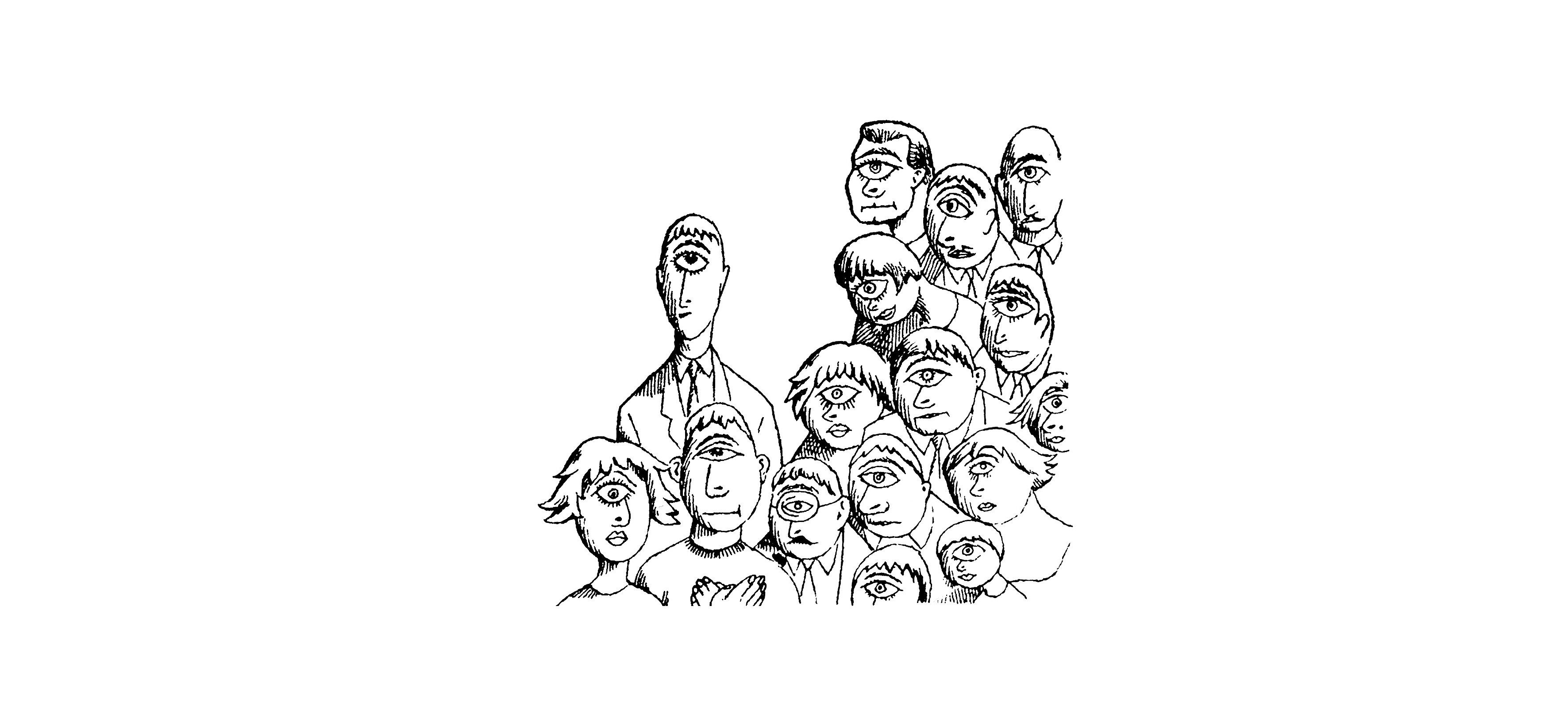

He spent half a century drawing illustrations, designing vignettes and the little hands that pointed “Przekrój”’s readers to the next page, coming up with cover layouts and typesetting pages – in short, he was one of the creators of “Przekrój”’s distinctive style. Indeed, he invented our magazine’s visual language. In this piece, Daniel Mróz – a great artist, a tender father, a colourful Cracovian, and a man who became an institution in his own right – is viewed through the recollections of his daughter, Łucja Mróz-Raynoch, and his colleagues, Mieczysław Czuma and Adam Macedoński.

These are excerpts from the monograph Przekrój przez Mroza by Janusz Górski and Łucja Mróz-Raynoch, published by the publishing house “czysty warsztat”.

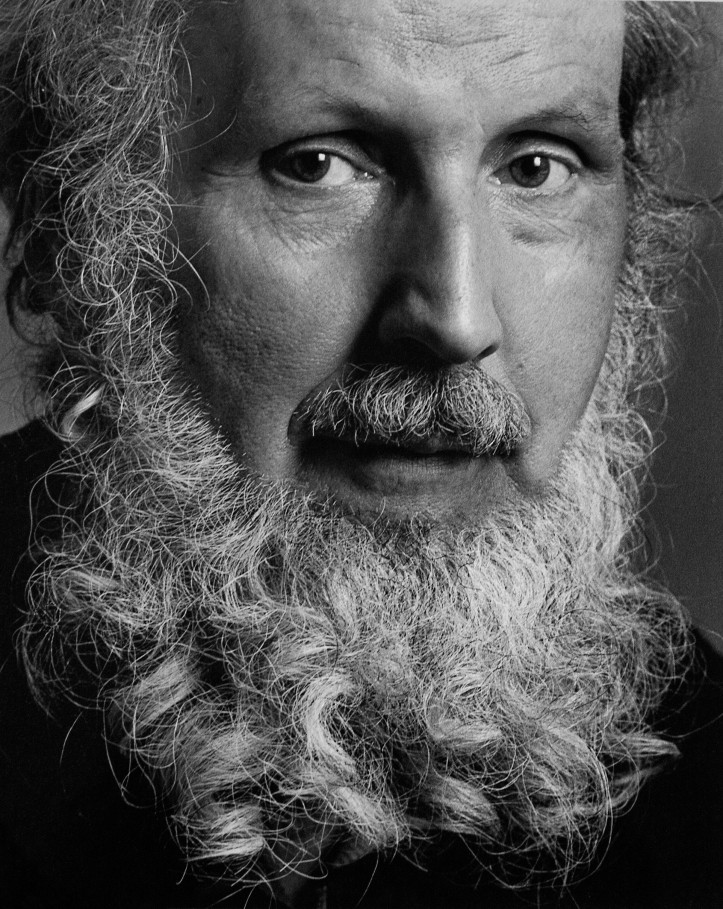

Łucja Mróz-Raynoch: I’ve been told that people were afraid of my father because he was big and strong, and when he got upset he roared like mad – the sound would literally stop you in your tracks. Well, he was nearly 6.5 feet tall, and he was once a boxer, so I guess he could be quite intimidating.

Despite all that, my father never showed any signs of physical aggression, unless someone accosted him. Besides, that’s what he taught me: when someone accosts you, assume the worst. Don’t worry what will happen, just defend yourself as if that person meant to kill you. That’s probably because before the war my father did come close to being killed. One day, he was walking with his brother Sokrates and his fiancée – and I must add that his brother, though rather stout and very tall, looked rather wimpish. Some fellow accosted Sokrates, and father came to his defense. Seeing such a powerful opponent, the attacker drew a knife. Luckily, his aim was a bit off, and the blade missed my father’s heart by half an inch.

He had an explosive temper, yet his anger was quick to subside. When I was a kid, my father’s yelling made me very scared. It wasn’t until I grew up that I realized that it was just a smoke screen, a kind of armour to hide his vulnerability. Being a hothead, Dad was not just impatient – he also enjoyed teasing others, so we’d sometimes lock horns. Adolescents are known to be very serious about their views, and when I called something “black”, he’d reply, as a matter of principle, that it was actually “white”. Obviously, things ended with us screaming and yelling. Fortunately, this never lasted long, and he would soon come pat me on the back and say, “There, there, you’re feisty, just like I’m feisty.”

Adam Macedoński: He was certainly a genius.

Mieczysław Czuma: Daniel had worked with Funio Berdak and Zygmunt Strychalski, who was already retired. After the latter passed away, Mróz asked me to find me someone who could help him. The year was 1974. I went to Marian Konieczny, then the rector of the Academy of Fine Arts. He welcomed me and said: “I’ll give you the best person I know.” That turned out to be Andrzej Kowalczyk. He and Mróz hit it off immediately, and they made a great duo. Mróz was obviously the master, Andrzej the apprentice. Mróz valued him highly, because Andrzej knew an amazing amount and constantly learned new things. He was interested in history, costumes and weaponry – he was like Matejko, with his grand style, colourful characters, and details of clothes from all periods in history. And Mróz was simply being Mróz, doing extraordinary things.

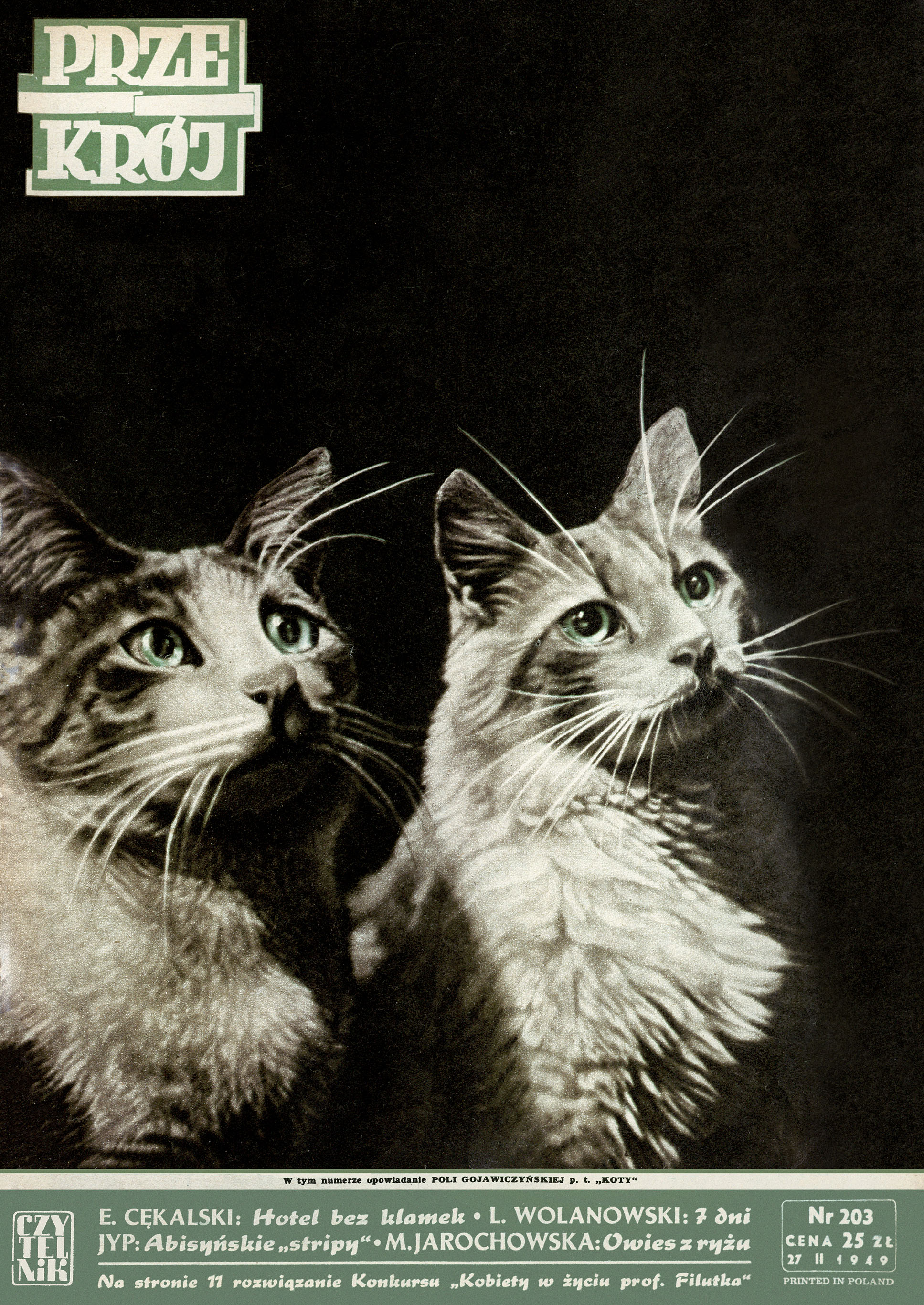

The typesetting was done by Mróz and Kowalczyk, and the last page was always made by Berdak. Mróz took on the most important task: the covers. In my day, he authored some phenomenal covers. He also made illustrations for short stories and stepped in with his vision where necessary. […]

When we were working on a “Przekrój” issue, Mróz had the freedom to work as he liked. Whenever he was designing a cover, he would tiptoe around the issue, without fully revealing what he intended to do until the last moment. His ideas were born in the editorial offices – in torment and in silence, amid terse, even gruff replies. He would then gather up all those rolls of paper and take them home. The following morning, after feeding the cats, he would take them back out of his briefcase. Whatever he did, it was excellent.

He had his own catchphrases. For instance, we would often end up ‘dillying’ (getting behind schedule) with a magazine issue because of Mróz, who would pace and think, think and pace. But when Mróz was ‘dillying’, everyone over at the printing house understood. He kept paying visits to them for as long he could. He knew everyone over there, and everyone there loved him, so when an issue was delivered late because of Mróz ‘dillying’, things were always sorted out in the end. In order to mollify the printers, a gathering with the whole printing house was held once a year. We’d collect money, and I’d find some castle in Pieskowa Skała or somewhere outside Kraków, and there was food and booze – as always with printers.

Łucja Mróz-Raynoch: He was essentially a sombre fellow, extremely pessimistic about the world’s future and terrified by mankind, by people’s cruelty towards one another and towards nature, and also by the ruthlessness of nature. But he liked individual people and believed in them, and he had a sense of humour – quite a dark one, but he told jokes and enjoyed the little things in life. I don’t think it was easy for him to live with all these contradictions and contrasts.

***

Dad collected old books and magazines with drawings in them. He took clippings or rephotographed them to make collages. His friends, especially his good friend, the geologist and bibliophile Stanisław Czarniecki, would bring him odd copies of old textbooks and clippings from old catalogues. They would meet and spend hours browsing through books in the famous antique bookstore on Sławkowska Street, run for years by Stanisław Cieślawski.

In 1977, reproductions from 19th-century zoology textbooks were used to create illustrations for Robert Stiller’s poems Zwierzydełka. They continued the fun they had creating a fantastic bestiary, and “Przekrój” announced a competition called “Anonimalia” for inventing names to give those hybrids.

When I was a kid, I spent hours paging through books about travel, wonders of the world, animals, plants, minerals, machines and astronomy. Magnificent illustrations, covers and prints made by people who considered themselves craftsmen and from whom my father learned all his life, watching the way they modelled space and used contrasts between light and dark and adapting it into his style of drawing. Also, he kept heaps of clippings – after all, they might come in handy someday.

Back in the times when no-one even talked about sorting waste, my father would manically take everything to pieces. When the possibility first emerged, he would meticulously collect aluminium milk bottle caps and return them to the stores. He also sold glass and paper back to collection points, and used every piece of paper for his drawings – nothing should ever go to waste. He used to say that we should try to make sure the world didn’t get flooded with trash. A prophet?

Adam Macedoński: When I saw Daniel Mróz’s drawings in “Przekrój”, the artist I imagined was an old, obese, bald man in thick glasses, leaning over a piece of paper, studiously dipping a thin nib in ink, and stubbornly drawing thousands and millions of little lines to create those brilliant drawings. Someone surrounded by plenty of them, because he never left home and he spent all of his time drawing. In my imagination, he was the very opposite of me. At that time, I was engrossed in sports and chasing girls, and I only drew and wrote because I had to earn a living somehow… Much to my surprise, Daniel Mróz turned out to be a young, handsome and athletic man, a muscleman with a benevolent smile…

Łucja Mróz-Raynoch: “Przekrój” popularized both Polish and global contemporary art in Poland. Dad had very fond memories of “Przekrój”’s “Picasso year”. He accepted every honest form of art, in other words art in which he could see individual efforts to achieve results through thought and hard work. That’s why he didn’t have much regard for the trends and fads that emerged in the 1960s, starting from pop art. He saw them as the commercialization of art. Although when op art appeared, it did interest him – as an inspiration for his use of halftone techniques. He was rather averse to hyper-realism, on the other hand. “What’s the effing point? We have photography, so what’s the purpose?” He saw it as a pointless display of skills.

***

He was very emotional and full of contradictions – on the one hand, he was fascinated by the world; on the other, this world also disappointed him terribly and appalled him. An atheist who constantly cursed God. To which I’d reply: “Who are you arguing with, if you don’t believe in him?” He needed to love people, but war had cured him of illusions.

***

When he was angry with someone, he would draw a caricature of that person and then throw it away, and that was the end of it. It was a shame, because some of those caricatures were excellent, though terribly spiteful. But my father would always say: “God forbid someone should find them and feel hurt.”

Mieczysław Czuma: In public situations, Mróz was generally quite reserved. He would say a word or two and enjoy himself, but in a passive kind of way. He barely spoke a word at weekly staff meetings. Everyone had something to relate, but Mróz would only murmur “yes” or “no”. And that would be an important signal as to what direction we should take.

Daniel Mróz had a profound sense of humor, but it was somewhat philosophically dark, quite British, and a little abstract.

Łucja Mróz-Raynoch: Father’s drawings often featured old automobiles. When he was a child, he had lived at Wygoda Street, next to which there were garages owned by Mr. Ripper, who represented different car companies in Poland and was the father of the famous pre-war rally driver “Jaś” Ripper. Dad and his brother would lurk around at the garages and then rush to Zwierzyniecka Street, following some of the more interesting cars as they headed downtown. The cars drove slowly, so they were not hard to keep up with. That was one of his passions, but one that was purely theoretical, because my father didn’t want to own a car. He said he was too scatterbrained, and he didn’t want anyone to get killed.

Mieczysław Czuma: When Daniel was a child, he would go, obviously with his father and his brother Sokrates, to Rakowice, an airport in the times of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and watch airplanes there. What about his love of cars? Before the war, the Mróz family lived at Wygoda Street, near Kossak Square. That’s where a Mr. Ripper, a car mechanic, had his garage. Back then, such people were rare. Wojciech Kossak, who lived at Kossak Square, bought cars from Mr. Ripper. Daniel together with Sokrates always waited near the garage and chased the cars leaving it all the way to the Main Square, the train station, or the Grand Hotel, and when they finally caught up with the cars, they would stop and look at them in admiration.