Rabindranath Tagore had two lives. For Europe, he was a mystical wise man, and for India, a troublesome prophet. This brilliant poet and thinker believed in human unity and a universal mind. He befriended Gandhi and Einstein, and founded a pioneering university to teach the wisdom of the East and West. What has survived of his belief in a united world?

He was one of the intellectual giants of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a genius in many disciplines—from poetry and prose to painting and music. He was also a pilgrim, presenting his universal spirituality from Japan to the US. After receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 (the first non-European to win the award), crowds greeted him everywhere and the elite took him for a guru, a spokesman for the cultural heritage of India, and a political commentator. Yet he chiefly considered himself a poet. Most of the time, in fact, he felt isolated. He had trouble making friends or even feeling intellectual kinships—throughout his life he had only a few such relationships. In his homeland he was embroiled in ethno-religious turmoil, overseas he struggled with being perceived through stereotypes of Asians. His ideals of freedom, the unhampered flow of inspiration, and spiritual development that transcended divisions, situated him outside of the epoch’s prevailing movements, watershed events, and social moods. In times when nationalism, racism, and militarism were on the rise—and which saw two enormous wars—his thoughts and works matured to become an antidote to these phenomena. The more the world succumbed to seeking differences and creating divisions, the more Tagore focused on what was deeply and incontrovertibly human. This is why now, when history has come full circle, his thoughts may bring solace; after decades of seeking commonalities and peace, the words “war” and “border” are again making their comeback.

In a Temple of Literature

Tagore lived to be eighty, and compared his time on Earth to the life of a tree—he was independent, yet joined with nature. He thought development was the foremost task. A simultaneous belonging to the natural and humanist worlds seems at the heart of his convictions. He was indebted to his predecessors for much of his outsider stance, preaching the unity of all existence. He was born into a privileged and rebellious family. One of his great-grandparents, a Hindu, married a Muslim, and from then on, Tagore’s family was sidelined in the Bengali social structure as odd and tainted.

The spacious family residence, Jorasanko Thakur Bari (the House of the Thakurs, whose noble name the British pronounced “Tagore,” and so it stayed), still stands in the north of Kolkata. One need only enter the gate to feel the peace and calm, away from the bustle. Yet apart from silence, the house offers little: a few pieces of furniture have survived, but the decorations, dishes, and books have gone. Young volunteers guide you through the drafty rooms, mainly talking about the crowd around Jorasanko after Tagore’s death in August 1941. The poet’s eldest son could not cut through to the banks of the Hooghly River, a mere twenty minutes’ walk away, to carry out the final cremation rituals. Another relative performed them in his stead. Today there stands a small monument where the cremation was held. It is good to visit in the morning, to have a look at the ritual bathing and the passenger ferries on the river. The crowd tore hair and scraps of clothing from the poet’s body as it was carried. Tagore was treated like a deity, against his will and the philosophy he preached. Some of his manuscripts and memorabilia is found at Shantiniketan, in a museum in the school he founded in a village outside of Kolkata. Most of his possessions were stolen, however, including his Nobel medal. The bare walls in Jorasanko are thus best visited with a volume of Tagore’s poems in hand. Or by sitting a while in the courtyard and waiting until an admirer begins humming one of his songs. For many Indians, this home is a temple of literature. Nearly everyone knows one of his poems by heart, and will not hesitate to recite it on request. Many artists would dream of receiving the love he is given. For sophisticated readers, he remains a genius of phrase, rhythm, and revolutionary constructions; for the masses, he is a poet who speaks to their heart, as he wrote in a language that was understandable, almost casual, rendering their longings, sufferings, and joys.

The 18th-century home and garden with its courtyard was on land received for service by Rabindranath’s grandfather, Dwarkanath (1794–1846), one of the wealthiest people at the time in Kolkata. He made a fortune with the East India Trading Company, befriended Charles Dickens, and dropped in on Queen Victoria’s court. He knew Persian, English, and Sanskrit. As a zamindar, a great landowner, he also traded indigo and coal, and founded one of the first Bengali banks. He was among the most influential Indians of the colonial era, and its perfect offspring: he had an aristocratic bearing, kept up with cosmopolitan fashions, traveled, and took advantage of what Europe had to offer. Influenced by the studies of Ram Mohan Roy, an important social reformer, he joined the Brahmo Samaj monotheistic faith group. It is thought that Roy triggered a nearly two-centuries-long movement known as the Bengali Renaissance. The movement prompted intellectual ferment and civilizational ambitions among Indians. It taught them independence and a consciousness of their culture as opposed to British dominance. Bengali schools were founded, and new political movements and forms of art emerged. The capital of scientific research and creative exploration was Kolkata, but ripples were felt across the entire subcontinent. Without this intellectual, spiritual, and artistic revolution, the later collapse of British rule is unthinkable, as Indians had long wallowed in what Tagore described as apathy and lethargy. Oppressed by European power structures, they fought hard to recognize their own agency and subjecthood.

The last outstanding representative of the Bengali Renaissance is thought to be Rabindranath Tagore. He supported education in the Indian languages, liberated literature from its rigid grammatical structures, wrote hundreds of songs inspired by the folk traditions of wandering mystics (or bauls), as well as plays and novels filled with great ideas, the dilemmas of the era, and flesh-and-blood characters. The emotional and psychological credibility of his protagonists brought him a growing readership. In the song “Jana Gana Mana” he described the beauty of the Indian landscape and the highest spiritual essence saturating it. He achieved this so movingly, simply, and universally that the lyrics came to accompany the Indian independence movement for four decades. In 1950, the first verse became the anthem of the democratic Republic of India.

On the Native Scene

Participating in the great reawakening of India, Rabindranath chose a path that was different from his anglicized, collaborating grandfather Dwarkanath, who, owing to his place of privilege in the early 19th century, could take on an unknown, revolutionary creed. The Brahmo Samaj community was based on the spiritual teachings of the Upanishads, the later philosophical writings of Hinduism. It rejected a doctrinal reading of holy writ, the widespread cult of deities, and the existence of avatars, or incarnations of gods. Its adherents spoke out against the caste system. Thus a revolution occurred in the Tagore residence; customs changed, and even women who did not approve of the revolution had to adapt to it. Following the sudden demise of Dwarkanath, the family empire collapsed. The sons did not wish to do business with the British Crown, and had to pay their father’s debts for years. Over time, however, they managed to rebuild their financial status, and above all, the prestige of a family promoting art, publishing a magazine, and remaining in the era’s intellectual avant-garde.

Rabindranath was born in Jorasanko on May 7, 1861 as the youngest of fifteen children. He seldom saw his father, Debendranath, or his mother, Sarada Devi. The latter died when Rabi was only fourteen. He was surrounded by servants, cooks, maids, equerries—everything a Bengali family could need. The servants washed, dressed, and recited excerpts of the Ramayana epic poem to him. They strolled with him to the garden, which was his enchanted place. Growing up in a multigenerational home, however, was not to his liking. He felt oppressed by the hierarchy, which gave an overwhelming advantage to the elderly. He did not support his father’s conservative views, which restored some of the caste rituals, only allowed women to be homeschooled, and gave away daughters to be married at eight years old. Tagore refused to go to an anglicized school. He did not wish to be subject to intellectual training to become a typical bhadralok, a Bengali gentleman.

Thus, beginning at fifteen years of age, he had private teachers who ensured him a complex education. He learned Bengali, Sanskrit, and English; geometry, arithmetic, history, and music. He practiced Indian wrestling and gymnastics, he even had a home laboratory for the hard sciences. The very fact of growing up in Jorasanko was an arts academy of sorts; many family members were involved in art and writing, they published and performed. His uncles sponsored newspapers and were literary patrons. Small wonder that Tagore’s talent flourished on the local scene—while still a teenager he published several volumes of poetry, later he began writing dramas and historical novels. His father sent him twice to England for courses run by University College, London, but in 1880 Tagore was called home to oversee the family’s affairs in the village.

At twenty-three, he married Mrinalini Devi, a ten-year-old girl from a village family. They spent nearly two decades together, during which time they had five children. Mrinalini died suddenly of an undiagnosed illness. Tagore took care of her and wrote of her with tenderness, but he forged a much closer spiritual bond with his brother’s wife, Kadambari Devi, to whom he dedicated poems and whose suicide shook him profoundly. In the years that followed, Tagore was to undergo more losses, including the death of his children: his daughter Renuka and his son Samindra. He spent several years in the Bengali countryside and in Odisha, where he looked after the family properties. He lived on a boat. He later described this time as lonely and depressing. But this was when he came into contact with people from outside his privileged sphere. He encountered everyday village life, work on the farm, and down-to-earth problems—all that he learned was later reflected in his thoughts on Indian unity, in poetry and song praising Bengal and the modest life.

The Great Awakening

The turn of the 19th and 20th centuries clearly reinvigorated India—there was more and more talk of Indian identity and self-determination. There was the formation of the Indian National Congress (co-founded by Gandhi), a party that exists to this day and, with a great social movement, led to Indian independence. Tagore gave up his solitary life, returned to Kolkata, and became involved in Indian social life, which had become vibrant after years of stagnancy. He edited a few magazines and published articles on politics. Unlike the members of the main independence movement, he did not support cooperation with the British government. He believed that the colonizers should be given no role in the government. He sought to show Indians that they could be independent. He wrote that instead of flapping their wings in a cage they should question the cage’s existence. For that, they had to know their identity; to recognize they were fully-fledged creatures capable of standing on their own two feet. Years of colonization had instilled a sense of inferiority, a learned helplessness. In several dozen political essays, speeches, and lectures, Tagore contended that they had to relinquish the false prestige of being almost British (like his grandfather) and enjoy the dignity of being Indian. In this way, he pointed the way for the entire independence movement. He spread the idea of a state based on unity in diversity, combining ethnic, linguistic, and religious traditions into one nation.

This idea—essentially the concept of a multicultural nation—was later developed by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India. After centuries of British dominance and the strategic stoking of divisions—but also the whole experience of the inhabitants, who identified more as members of small societies determined by faith, descent, and language—the idea of creating a single organism was groundbreaking and a great test for society. Tagore stressed that in Europe the state was accountable for organizing social life, and in India, society itself. And thus it should stay. This is why he saw the central task as building a sense of one’s own identity, training atma-śakti (the power of the self). Self-sufficiency was encouraged. Tagore proposed a few practical solutions: building an irrigation network to join rural households, educating children of various social groups in schools, setting up a system of micro-loans for farmers, solving conflicts through out-of-court agreements, etc. Unity has to be learned in practice, patiently filling the ruts of passivity and hostility every day. Otherwise, Tagore believed, there could be no true resistance to British rule.

Yet the independence movement leaders did not listen to his recommendations. They found them inconvenient. Tagore said that the colonizers were not to blame for everything. That the Indians themselves were good at seeing one another as better and worse. That the elite despised the inhabitants of poorer cities and Muslims, that India produced no public sphere, only communal zones, immune to foreign influences. They had no space for exchange, a symbolic or real agora, for meeting and working together. Bengali nationalists did not like having their political weakness put on show. Tagore was also alone in criticizing the campaign to boycott British goods. He condemned the military operations and terrorist attacks of some independence activists. He considered them heroic, but misdirected and politically ineffective. The only place where he saw true emancipation was in culture—only through building the consciousness of a community would it be possible to create a society of people separated by the boundaries of religious practices and languages. He agreed that resisting the British could unite the Indians, but only for a moment. To create an Indian nation, it would be necessary to go to the people, to delve into the most remote corners and the smallest communities, to cooperate, to join the lands through socio-economic programs. Nor did Tagore support Gandhi’s plan to bring back hand-weaving and other traditional crafts. Though he wrote a novel in the 1920s about the danger of mechanizing life and work, Tagore did not reject industry and scientific progress. He saw them as necessary to a good standard of living. These differences, as well as the fact that Tagore’s thoughts failed to resonate, caused him to withdraw from political activism before World War I, focusing instead on education and literature.

A University in a Tree

Tagore’s far-sighted and pragmatic thinking may seem surprising, particularly since he was primarily considered to be a poet. Despite his political commitment, he found time to write. In the early 20th century he wrote his most famous novel, Chokher Bali (1903) depicting the sufferings of a young widow sentenced to deny her emotions and relationships for her entire life (traditionally, widows in India were not allowed to get remarried, participate in ceremonies and meetings, wear jewelry, use spices, or experience joy in life). A few years later came Gora (1907), a novel about a nationalist who undergoes a major transformation: from a fanatical Hinduist to an Indian identity enthusiast. Tagore’s earlier novels were symbolic and historical; he later matured to portray life in all its realism and complexity. He was able to give his characters true dilemmas. He depicted the drama of a girl suffocated in a bourgeois family. Or an intellectual who, upon hearing of his true origins, experiences a shock and has to rethink all his opinions about the world.

Rabindranath became known as a keen observer, keeping close to everyday life. He wrote openly about sexuality, breaking taboos. He did this using a language that spoke to the reader, rejecting the “high” literary Bengali and its hermetic nature. He wrote a great deal; at the turn of the century alone he published dozens of patriotic songs and around ten volumes of poetry. He began writing spiritual poetry, whose peak achievement was Gitanjali: Song-Offerings (1910), inspired in part by the work of mystic and Sufi poets such as Kabir, Hafez, and Tulsidas. Tagore himself translated Gitanjali into English (with editorial help from the outstanding Irish poet W. B. Yeats), gaining recognition in Europe and the US. This volume expressing a desire to be one with God—understood as a being that suffuses all of existence—sufficed to bring him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. The West immediately accepted Tagore as a spiritual wise man from the East, and this label stuck. His other works, other incarnations, and aspects of his oeuvre are little-known in the Western cultural sphere. For this part of the world, Tagore shone as a mystic of poetry. The long-bearded, kurta-wearing guru was a living fulfillment of the Orientalist imaginings of Asian wisdom. Meanwhile, he had another truth for the world, which he tried to spread and bring to life.

In 1901 he began carrying out his most important project—an academy and development center in Shantiniketan, a Bengali village. He called it Visva-Bharati, which might be translated as “an integration of India and the world.” This was what he yearned for, to make it part of the cultural legacy of humanity, in which it would take its rightful place. He began studying with five students, dreaming that soon teachers would converge here from all over India and other countries as well, growing together, exchanging knowledge. Shantiniketan was to be unlike universities, where students were made into passive receivers of set ideas. Here truth and understanding were to be born between teachers and students, in movement, in nature, in the open air. Classes were held under trees, or even in their branches. The atmosphere was more like an ashram than an academy.

This place for meeting and exchanging Eastern and Western ideas remained the center of Tagore’s efforts for years. It was also his financial strife, because money was short from the very beginning. He committed all the proceeds from his publications, lectures, and appearances around the world, to maintaining the school. He went on long international tours, seeking intellectual fraternity in Japan, China, Bulgaria, Switzerland, France, Great Britain, the US, and Canada. He also traveled to earn money to support the school. Along the way, he met some great thinkers, many of whom later visited his university, especially after he won the Nobel Prize. Future leaders of free India studied there, including Indira Gandhi. To continue running the center, Tagore had to regularly draw loans and sell his wife’s jewelry. Just before he died, he wrote to Gandhi with a request to take care of Shantiniketan—his greatest accomplishment, the most valuable fruit of his earthly journey. Gandhi promised to take care of the school, but was assassinated a few years later. Financed by the state, the academy chiefly held to the teacher’s principles. Yet ever since 2008, when right-wing nationalists took power in India, it has increasingly been a campus for ideologies far from Tagore’s intentions. The present government promotes an ideology of “India for Hindus”; it supports a conviction that only adherents of Hinduism can feel at home there, inspiring and supporting acts of discrimination and attacks against Muslims.

At present, classes at Visva-Bharati are held according to strict rules, and the teaching staff has been replaced. Prime Minister Narendra Modi grew his hair and beard for six months—according to many, including the creators of internet memes mocking this metamorphosis, he hoped to physically resemble the brilliant poet. Later, he donned Tagore’s trademark sukmana and posed for photographs in Shantiniketan. He is not alone in wanting to govern souls and minds by seizing power in the country’s intellectual Mecca. Mamata Banerjee, Prime Minister of West Bengal and a populist renowned for her crass behavior and remarks, declared herself Vice-Chancellor of the academy and recently published a volume of her poetry. All of India is experiencing an ideological assault on its academic and educational institutions, as xenophobic and uneducated politicians seek to make them their own.

Waiting to Be Rescued

In the last two decades of his life, Tagore traveled widely and wrote admirable and popular novels on themes including sexual discrimination, economic inequality, and classicism in India. He also began painting, and with some success. He contemplated the world, and enthusiastically supported a spiritual union between China and India, convinced that these great and ancient civilizations had much to offer one another. With Gandhi he discussed the nation’s ethno-religious conflicts and the dangers that came with stoking hatred. The closer they came to Indian independence, the more the world seemed divided and consumed by the demons of fascism. Tagore’s vision of a united humanity ultimately collided with reality—deepening conflicts and the amassing of armies.

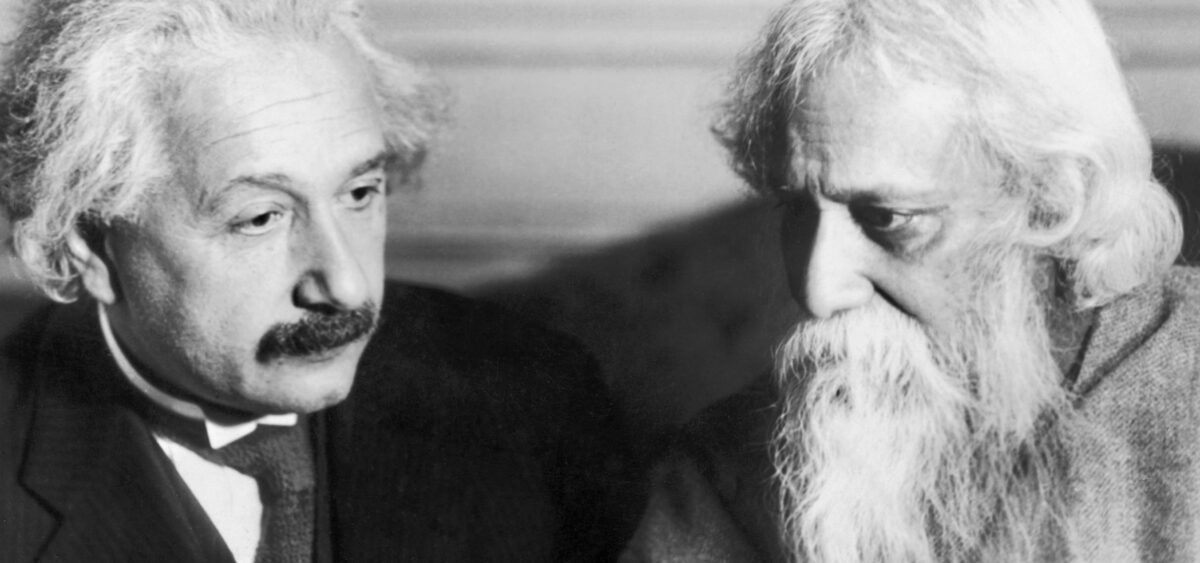

In spite of everything, Tagore remained true to his convictions of the universal nature of life, the universe, and humans. He consistently rejected religion, believing solely in an Eternal Spirit saturating everything, in a union between what comes from nature and humanity. He believed that human minds are joined, forming a whole he called the universal mind, a meta-consciousness. He argued this point with Einstein, who thought it was unscientific. When asked if a table stands there and exists because I see it, the physicist replied: no, the table is actually standing there, objectively, regardless of the human eye. The poet disagreed. He believed the existence of the table was possible only in the realm of the human senses, that its facticity was illusory, and our senses conspire to design an image of the universe they alone can perceive. Outside of it, he contended, was another truth. Although these two great and beautifully differing minds have now departed, their dispute lives on. Science and spirituality, however, are presently closer together. Tagore’s conviction of a universal energy that creates everything is in many ways similar to the latest trends in physics. Researchers presently working in the West (many of whom come from Asia) are gradually finding new ways to measure and define phenomena previously described by the philosophers of the East. And although Tagore probably would have perceived globalization as a threat to authentic human unity, he would have appreciated the growing number of connections and intercultural similarities. Humanity remains focused on superficial differences, it falls under political spells that create divisions and conflicts. But beyond this clamor, trees grow, and a cosmic unity is increasingly felt. Climate change at present most reminds us of the conjunction between humanity and nature, and here humans are its causes, participants, and victims.

Tagore liked to be in the world, looking for friendship based on intellect and spirituality. At the same time, however, fame wore him down. Raised in a home without deities, he knew that idolatry was no defense against, as he phrased it, “the hunger of the eternal dust”; not only would he expire, but a similar fate was in store for his ideas and works. A ten minute’s walk from the Jorasanko house, where he perished following a kidney operation in 1941, takes you to the Chaitanya Library he helped create. It was built in 1889 as the country’s first repository of books for Indians (the National Library was national in name only, as entry was reserved for the British). There are thousands of books there, many over one hundred and fifty years old. They are written in Hindi, Bengali, English, and other languages. Now no one borrows them or reads them. They are rotting on the shelves, attacked by mold and termites. Surrounded by silence and darkness, they are waiting to be rescued. The son of the last librarian is trying to save this heritage, he is looking for sponsors, but the library remains the property of around a dozen nonagenarians who are still alive and reluctant to change. The books are closed up on the upper levels, and a group of poor neighborhood children gathers on the ground floor every evening. Volunteers help them with their lessons, teaching them the basics of math and Bengali. Outside is the daily rumble of Beadon Street, a legendary avenue where some of the most important theaters and Bengali independence associations have operated. This is where Tagore participated in marches and made speeches. This is where his songs were sung. This is where his books will die, consumed by the eternal dust.

A Glossary for Understanding India

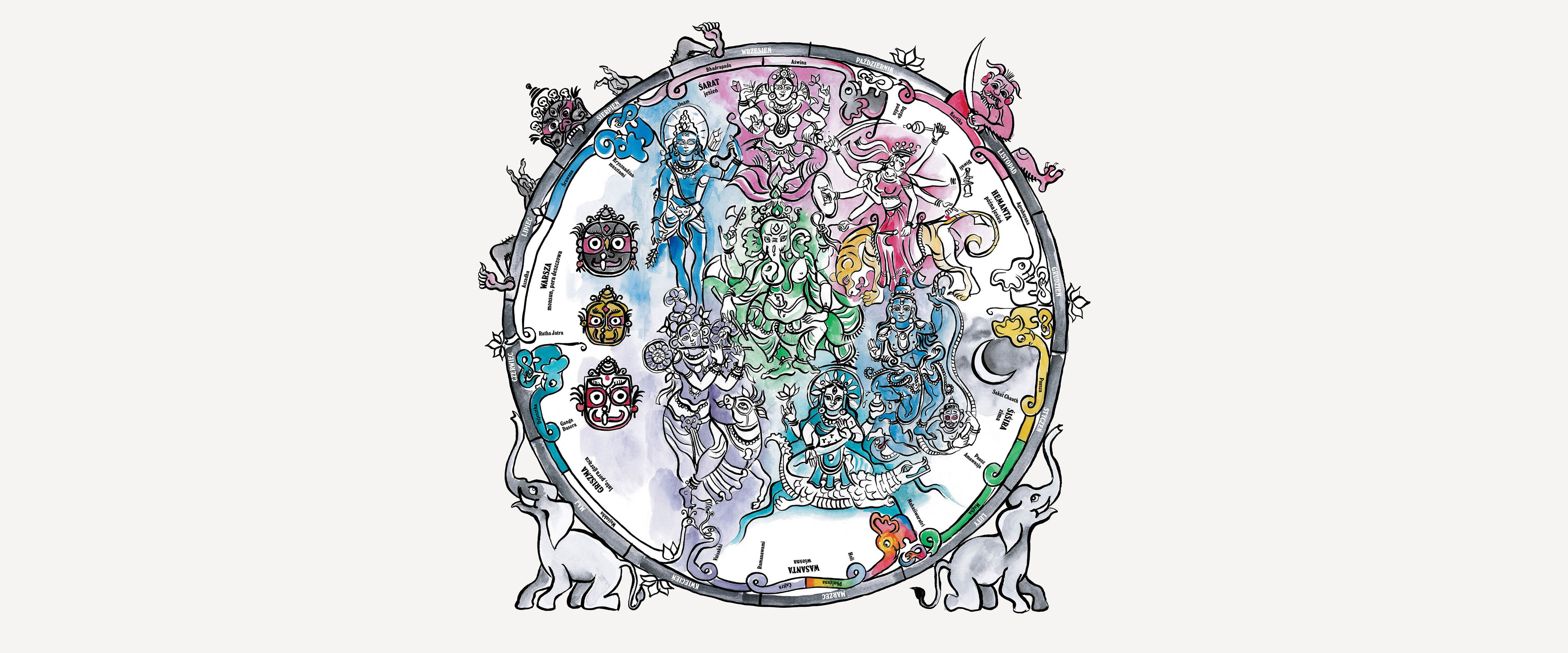

Dharma—an ambiguous term that appears in Hinduism and Buddhism. Definitions include: law, truth, a set of rules, a life’s path.

Hinduism—the world religion with the third-largest number of adherents, with hundreds of diverse sects. Everything attached to it—its holidays, beliefs, etc.—is defined as Hindu (and not Hindutva, a word associated with radical religious nationalist movements).

Indian languages—a large group of languages with a variety of alphabets. There are twenty-three official languages in India, though Hindi and English have special status.

Yoga—a system of Indian philosophy that joins body and spirit. In the West it is sometimes erroneously perceived as mere gymnastics.

Yoga Sutras—an ancient treatise describing yoga, written in the form of aphorisms (sutras).

The Upanishads—the most important religious/philosophical texts in the Vedic tradition. They contain some concepts central to Hinduism, such as saṃsāra (the eternal journey, the constant cycle of birth and death). They are the most recently-written part of the Vedas.

The Vedas—the oldest and most fundamental texts of Hinduism (in Sanskrit veda means “knowledge”).

Bibliography

Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi. Rabindranath Tagore: An Interpretation. Penguin Books India, 2011.

Ghosha, Nityapriẏa. Rabindranath Tagore: A Pictorial Biography. Niyogi Books, 2011.

Tagore, Rabindranath. The Definitive Tagore. Rupa Publications India, 2017.

Translated from the Polish by Soren Gauger