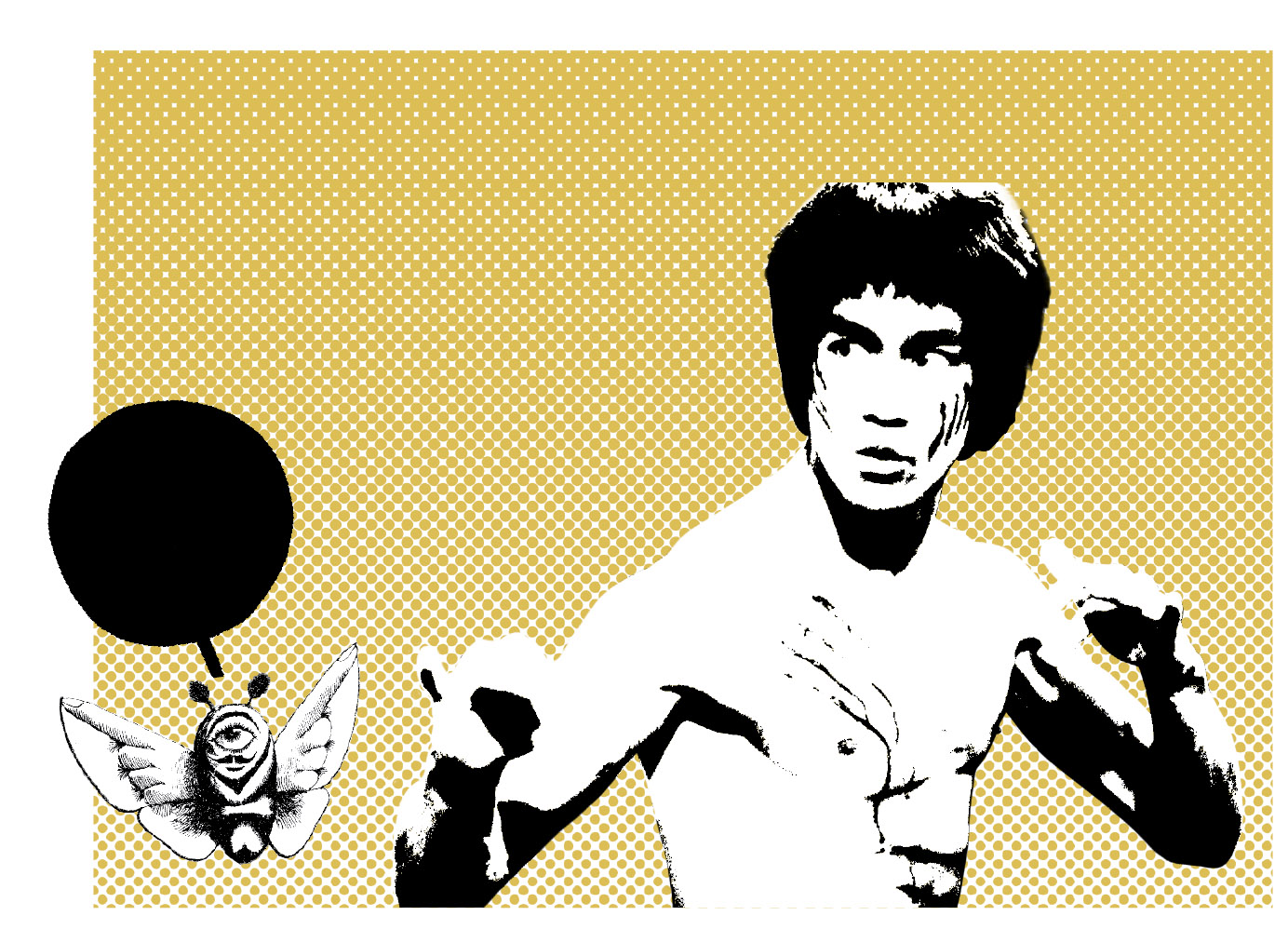

The heroes of Bruce Lee’s films resemble Benya Krik from Isaac Babel’s famous Odessa Stories – they say little, but are always to the point. This is in keeping with a rule often articulated on-screen (if they ever do speak) and repeated regularly off-screen by the man playing those roles: the basic aim of human life is to honestly and fully express yourself. Speech is merely one means of attaining it. Another (and perhaps the most important) is movement and, hence, the body.

How can one achieve this? How does one express oneself fully? It is good to start by being aware that all outlooks, systems and styles – especially fighting styles – primarily restrict us. Therefore, we should reject them and be like water, which, since it is formless, always assumes the shape of the vessel in which it is contained. A moment later, it can be poured somewhere else and will instantaneously adapt, like a chameleon. Water is in constant motion; an infinite transformation process, elusive, unlimited, absolutely free. That is the ultimate aim of existence. Nothing is more important.

This rule – be water – recurs in almost all of Bruce Lee’s public outpourings. Interviews, screenplays, private conversations, advice given to his students, letters to friends, manuals on Jeet Kune Do (the “style without style” that he invented), and the several dozen philosophical, psychological and spiritual texts compiled into the book Bruce Lee: Artist of Life (published 2001, ed. John Little) with a foreword by his widow, Linda Lee Cadwell. At the end, she writes that, because her late husband “chose the path of self-knowledge over accumulation of facts, and the path of self-expression over image enhancement, […] he did reach his destiny with a peaceful mind.”

In fact, contrary to appearances, this kind of philosophy has very little in common with the traditional Eastern schools of spirituality and thought that Bruce Lee undeniably felt he had inherited. His philosophy was rather that of a man who started a fashion for the Orient in Western cinema and became an iconic martial arts master; someone who fought with his perfectly trained mind as well as his fists. Thus his philosophy was largely descended from Western sources.

And this was by no means just because the young Lee had studied Western philosophy at the University of Washington before achieving international fame. The issue is not what he studied, but when and where. If one were to sum up the beliefs and essential background of the creator of Jeet Kune Do, the answer would be obvious: Bruce Lee was principally a child of the American 1960s’ counterculture, with its spirit, buzzwords and desires.

It is no accident that, from his early student years, his favourite books included classics of ‘new spirituality’, such as Alan Watts, an American thinker and writer disseminating a Western version of Taoism. Or the Hindu teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti, who, as a child, was proclaimed to be the reincarnation of Christ by C.W. Leadbeater and Annie Besant (Helena Blavatsky’s successor at the Theosophical Society), and was later active in his own right, preaching radical freedom from all social, religious and conceptual restrictions. Or Fritz Perls, the founder of Gestalt psychotherapy, and Abraham Maslow, a pioneer of psychology and humanistic psychology. Nowadays, counterculture scholars have no doubt that these and other authors best defined, or expressed, the spirit of the age.

What were its main features? First, the awakening of ‘hidden potential’ (whatever that might imply). Second, introspection or an interest in spirituality and the mind, rather than engaging with the surrounding world. Third, an affinity for exotic, preferably Eastern spiritual concepts, and a shift away from Christianity as an oppressive religion focused on feelings of guilt. And, fourth, the full (self-)realization that one’s self is shackled by social, moral and religious conventions – the chief goal for any spiritual path and psychological development. This was the core of the message that Bruce Lee adopted, adding elements of Taoist and Zen philosophy. As the vehicle to establish this spiritual/philosophical conglomerate, he used Chinese martial arts, which he had been training in since childhood in order to achieve absolute mastery.

The essence of his approach was outlined in the book Tao of Jeet Kune Do, published under the auspices of Linda Lee Cadwell two years after his death. Lee began working on the book – a full presentation of his concept and vision of martial arts – in the early 1970s. Struggling with a severe back injury due to over-intensive training, he spent the best part of several months in a specially designed orthopaedic bed. At that time, he began methodically noting down his reflections on kung fu and the “technique of no technique”, as he often described the style he had created.

Reading this book is like an excursion through well-known terrain. Numerous phrases sound familiar and many of them, as we know for certain today, were lifted directly from books by the aforementioned authors, as well as the Zhuangzi, one of the fundamental classics of Chinese Taoism. The basic dominant theme is that fighters must strive for a degree of skill that permits totally free, unconstrained movements, using techniques not limited by any codified rules.

Fighters following the path of Jeet Kune Do are perfectly integrated with their own true inner selves at all times. Their actions are guided by ultimate freedom. They feel no fear because, thanks to intensive physical training, their bodies and minds are ideally synchronized, attuned to the universal flow of energy. While fighting, they do not attempt to win or lose, but simply move according to their inner dynamics, thus bringing the bout to to an automatic and effortles end. Their characteristics are simplicity, direct insight and intuitive, uncalculated reactions to their opponents’ actions. In this way – to quote Tang Lung, the hero of The Way of the Dragon, directed by Bruce Lee – “[by using their bodies well] even in the midst of violent movement [they can] honestly express [themselves].”

But is that really possible? It certainly is a beautiful idea, albeit less relevant nowadays than when Bruce Lee was alive. Dreams of fully revealing one’s hidden potential, integrating body and mind, and turning life into a kind of unimpeded flow of mental and physical energy (i.e. all the main dreams and ideals of the 1960s that spawned the New Age movement of the 1970s) are now mostly a thing of the past. At least, this is what sociologists researching contemporary culture maintain (e.g. Eva Illouz and Anthony Giddens). The language of humanistic psychology and assorted philosophies inspired by Oriental spirituality is now more modest, mostly promising better ways to adapt to the corporate realities of contemporary capitalism. Instead of “fully revealing one’s hidden potential”, they tend to cover increased efficiency at work and heightened emotional satisfaction.

However, this does not imply that the significance or effects of Bruce Lee’s message are lost today. Dana White, president of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, the world’s largest MMA (mixed martial arts) organization, has no doubt that Bruce Lee was the true father of the discipline. Breaking away from traditional divisions, not limiting oneself to techniques from any particular school, and actively creating a practical style that combines several classical martial arts – we have Bruce Lee to thank for all of this.

But his more profound accomplishments are also staggering. The consistency with which Lee strove for excellence in his life and martial arts was truly unique. Reading his notes and short philosophical essays, we see a man gripped by a desire for self-analysis and self-development. Most importantly, he attempted to proceed in full harmony with his own beliefs. Hence his methodical aspiration to fully integrate life, art and sport, and hence his acting-without-acting from around the time of The Big Boss, filmed in Hong Kong. He endeavoured to make no distinction between himself and his on-screen persona by applying the Taoist principle of wu wei (non-doing) to film. No pretending; no made-up, fictional characters. Integrating the image and the self in order to honestly and fully express himself, both in everyday life and the realm of fiction.

In that respect, Bruce Lee seems to have succeeded. After all, when we think of him today, we immediately imagine an iconic, one-of-a-kind fighter. His characteristic grimaces and accompanying yells, as he demolishes a pack of opponents in Enter the Dragon, are just as convincing as when he says with his characteristic emphasis, during his last ever interview with Pierre Berton: “Be water […] Now that, my friend, is very hard to do.”

Translated by Mark Bence