Androids may dream of electric sheep, but Soviet cosmonauts dream of flowery meadows and white birch tree-trunks. Fortunately, there was someone who painted their dreams and sent them along up into space.

The Soviet space-exploration dream left its mark in various forms. There are monuments and streets named after Yuri Gagarin in most cities and towns, numerous Cosmonaut Avenues and Cosmonaut Boulevards, countless statues of rockets and sputniks. There are space-themed murals and mosaics on buildings and bus stops, as well as sports venues and brutalist-style circus buildings shaped like flying saucers. There is also science-fiction literature, electronic music played on Soviet analogue synthesizers that once blasted from speakers in parks and department stores, and children’s films such as Visitor from the Future and Adventures of the Electronic. There are all the posters, stamps and pennants you can still find at any of the Russian barakholki, or flea markets. In the early 1980s, smoke-enwreathed dance floors were filled with dancers bopping to the hit of the band Zemlyane (meaning ‘Earthlings’): “Earth in the viewpoint that I see / Like a son missing his mother / We miss our Earth – we have but one […]”.

Meanwhile, behind this façade of pop-culture, hidden away in top-secret, closed-off zones, space scientists and engineers were busy working on important projects. The cosmonauts, although heroes and idols of the masses, were under constant pressure – space travel and preparing for it were both physically and mentally exhausting. They didn’t really have much of a say. How could they complain? After all, they were the chosen ones. During his first flight, Yuri Gagarin made the best of Spartan conditions, but someone had to blaze the trail for others.

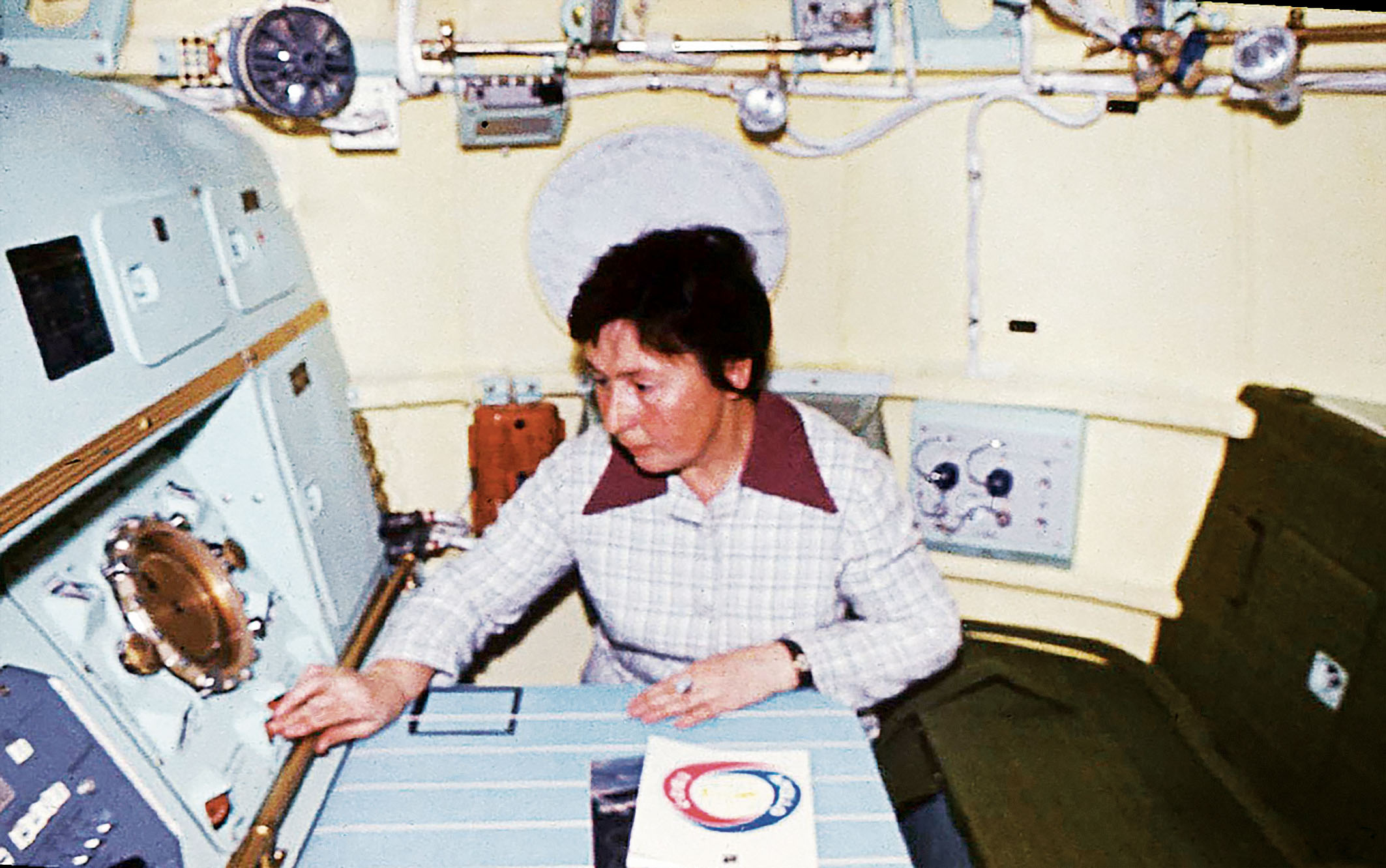

When preparations began for longer trips into space, a young graduate of the Moscow Department of Architecture, Galina Balashova, arrived at the Rocket and Space Corporation Energia (RSC Energia) near Moscow, the training ground for space teams. She was the only woman to join the team, brought in by Sergei Korolev, the greatest Soviet authority on spacecraft and rocket design.

Balashova clearly recalls that Korolev was the only one who understood that, apart from machinery to keep them alive, cosmonauts also needed some kind of private space and basic creature comforts. A home-away-from-home with simple furnishings and a comfortable toilet; bright colours to soothe the mind of a person who had been hurled out into the dark and cold cosmic vastness.

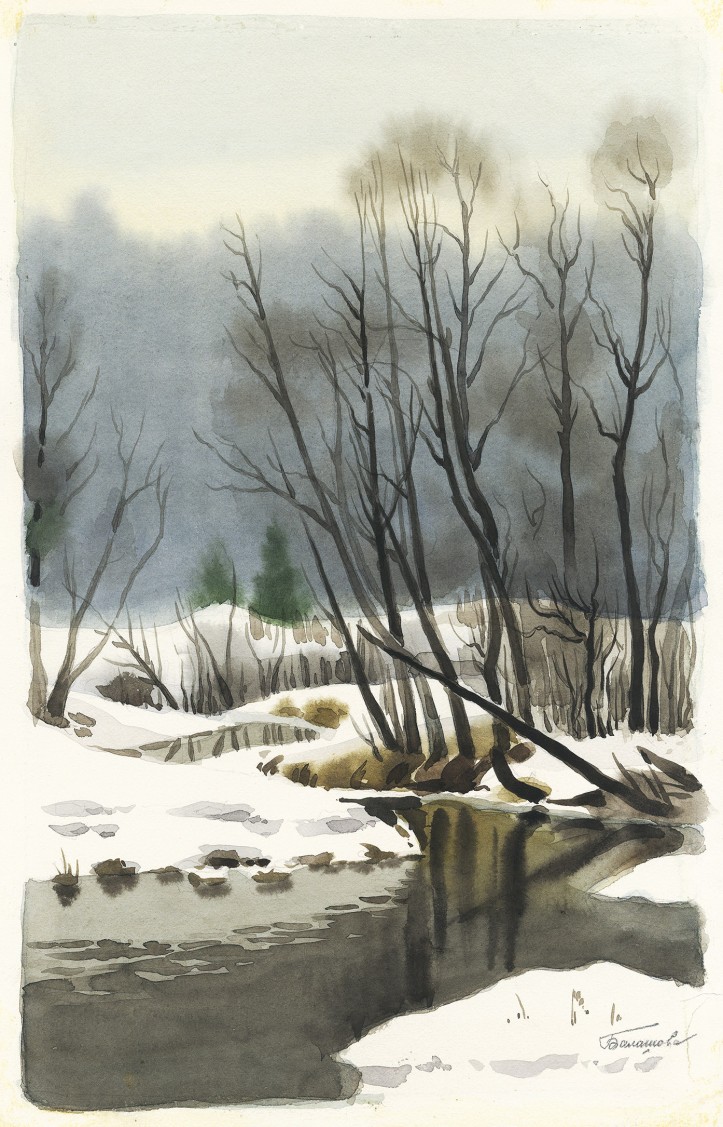

But how could they fit all that into a limited spherical space where the law of gravity doesn’t apply? Balashova puzzled over this while working after hours, as her official tasks were much more mundane: dealing with renovating the facilities and greening up the premises. In addition, she had been a watercolour painter ever since she was a child, painting landscapes of her native Moscow Oblast. “And we dream not of thunder at the cosmodrome / Not of the ice-cold blue of the sky / But we dream of grass – the grass beside our house / Green, green grass”. While the whole country was singing along to this Earthlings hit, nobody realized that in a space-town in the suburbs of Moscow, someone was painting melancholy pictures for the cosmonauts, of birch trees reflected in forest lakes. And that one day these paintings would end up destroyed along with the space capsules descending somewhere on the steppes of northern Kazakhstan.

The artist would have remained anonymous to this day, if not for the German architect Philipp Meuser, a specialist in modernism and an aficionado of retro-futurism. While digging around the depths of the Russian internet in 2012, he found sketches of orbital modules designed by Balashova, became fascinated with them and launched a private investigation. Shortly after, he found himself in a Moscow suburb, standing in front of a worn-out ‘Khrushchev building’ (a four-story structure for housing workers, dating from the Khrushchev era), where a grandmother in her eighties lived with her family. A retired space designer whose name meant nothing to anyone in Russia, but who was soon to be hailed as a pioneer of cosmic interior design.

Meuser paid homage to Balashova in the form of a richly-illustrated album entitled Galina Balashova: Architect of the Soviet Space Programme, published in 2015 in Frankfurt-on-Main by DOM publishers. That same year, an exhibition of Balashova’s works was held at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, which evoked wide interest in Germany. It was covered by all major media sources, and the well-known newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung affectionately dubbed Balashova the “granny from Korolev”. “To the cold world of rocket technology, Balashova brought her own emotional charge, her original take on inner harmony and genuine motherly care for cosmonauts,” wrote Meuser. The story took place in a small town known as ‘Russia’s space capital’. It was once called Kaliningrad, but since 1996 the town where RSC Energia is headquartered has been called Korolev, in honour of its guru space engineer, Sergei Korolev.

In 2018, the Moscow Oblast still looks very similar – rows of aggressively-lit 30-story high-rise buildings resembling those in Beijing fill out every inch of available space. If you look out the window of the elektrichka (suburban train) travelling north through the Moscow Oblast, the cramped Moscow agglomeration seems to go on forever – behind the noise barriers you see a sea of fuel cisterns stretching as far as the horizon. The town of Korolev is spread out between three train stations. There are fewer glass-clad skyscrapers out here, with concrete and corrugated metal dominating instead. The walls of RSC Energia stretch for several kilometres along the tracks, orange chimneys and missile silos occasionally peak out from behind them. The company’s red logo depicts its most famous product, known in all languages of the world as sputnik.

It is easy to come across references to ‘space’ in today’s Korolev, where the word (kosmos in Russian) is used in various contexts. Sidewalk advertisements for designer drugs from China promise kids a “cosmic trip”. A pink poster promoting a concert by Gela Guralia, the new star of the television show Voice 2, boasts: “A cosmic voice for the first time ever in the cosmic town!” At the entrance to the city, along Yaroslavskoye Highway, pedestrian viaducts twist and turn like opaque plastic earthworms. Above the large letters that form the word KOROLEV, there is a 10-story rocket-shaped monument. Other cosmic sights include a University of Technology banner depicting its graduates in caps against the photoshopped backdrop of the Mir space station, and a rocket-themed children’s playground. Next to it are murals in the style of illustrations from the popular 1950s children’s science-fiction book Dunno in Sun City by Nikolai Nosov. These include aliens with dolphins and robots battling cosmic octopuses with lasers. The local street art group is called Free Cosmos. More 1940s and 1950s architecture emerges as you walk towards the centre of the ‘old town’. A socialist-realist building housing the cultural centre with an obligatory colonnade is one of Balashova’s debut works. Nearby, nestled somewhere within a row of twin Khrushchev buildings, is her apartment. The elderly pioneer of cosmic interior design used to happily give interviews, but her failing health unfortunately made it impossible for us to speak with her.

The rabbit hole capsule

The Moscow Oblast is Balashova’s homeland. She was born in 1931 in the town of Kolomna into a family of déclassé aristocrats, the Bryuchovs. Perhaps it was her first childhood memory that sealed her fate: “My first memory is of a dark, wet rabbit hole, which I fell into one day in late autumn while walking in the woods in the village of Lobna where my father was a forester. The local rabbit hunters would dig these holes two or three metres deep. I fell into one while playing with my brother. Fortunately, my father noticed and saved me. I never forgot that feeling of claustrophobic helplessness,” recalls Balashova in Meuser’s book. As a bourgeois holder of a so-called ‘white ticket’, her father could only work as a physical labourer, somewhere in the provinces. His main passion, however, was watercolour painting, the secrets of which he would pass on to his daughter at an early age. Balashova’s family would spend the holidays around a Christmas tree decorated with cut-outs made from her father’s paintings. At one point, she also took painting lessons from an old master of 19th-century watercolours, Nikolai Polaninov. Balashova’s father paid him for the lessons with firewood, to which, as a forester, he had unlimited access. “I was extremely fortunate to be surrounded by the world of 19th-century masters, this wonderful dreamy world that is slowly disappearing.”

A few years later the Bryuchov family moved to the capital, as Balashova’s father got a job on the construction of the Moscow metro. In 1949, Balashova, a budding watercolourist, was accepted to MArchI, the Moscow Architectural Institute – a school with rich traditions. “Here again I was surrounded by exceptional teachers, lovers of beauty, who helped us develop a great taste.” At the Institute, she met and became friends with future celebrities including Georgiy Daneliya (director of such iconic comedies as Walking the Streets of Moscow, Afonya and Kin-dza-dza!) and Andrei Sokolov (an artist and future participant of space expeditions). Sokolov, along with cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, gained fame as ‘space painters’. As the narrator of an old newsreel says exaltedly: “Oh, what a pity that black-and-white film can do no justice to the fantastic range of colours in Leonov and Sokolov’s paintings! No Earthling could ever argue with the visions of painters who have glimpsed the cosmos with their very own eyes.”

In the future, Galina Balashova was to do the exact reverse: she would send her earthly landscapes up into space, incognito. However, as she always said, she learned the most important life lessons at MArchI: “Our teachers were genuine artists of the bygone era. At the end of the Stalinist era, they told us to be faithful to our tastes and to never blindly follow current trends.”

To Red Square via secret and confidential

As the Stalin era was coming to an end in the USSR, Balashova was just beginning her professional apprenticeship. As part of the new Khrushchev doctrine of austere form, spatial functionality and the “fight against unnecessary decorations in public space”, she was sent to Kuybyshev on the Volga. This was then the name of the town Samara, an old merchant city full of ornamented wooden houses. Balashova’s job was to remove these decorations. “It was an anti-architectural mission,” she would later say. While in Kuybyshev, she designed a cultural centre building in a minimalist and socialist-realist style. She was rescued by her old school friend, Yuri Balashov, with whom she had been romantically involved for some time. He proposed, they had a civil wedding, and they moved to the space town.

Balashov’s job as a physicist for OKB-1, the Experimental Design Bureau, was to protect the outer layer of spacecraft from burning up in the atmosphere. His wife was given a less spectacular job – she was placed in charge of renovation work on the company’s buildings, greening up the premises, and keeping stock of building materials. “But also things like removing unnecessary stories of the residential buildings adjacent to RSC Energia, so that their residents were not be able to see what was happening behind the company’s walls. We were all bound by strict confidentiality. Before being hired you had to fill out detailed questionnaires, and all candidates were thoroughly screened. We had to sign special documents describing our conduct, both at work and outside. For instance, we were prohibited from appearing in places visited by foreigners – exhibitions, theatres, concerts and restaurants were all banned. Even if someone had simply asked me on the street how to get to Red Square, I would have had to present a report to a special committee in writing.”

Instead of addresses, Energia employees had special stamps in their passports with the company’s post office box address. “I was constantly reminded that if I accidentally said something to someone, I could get up to eight years in prison. Inside the company, there were various levels of security – certain areas were only accessible to employees with special passes. There were armed security guards at the gates, and inside, the doors had codes, like safes.”

For the first few years, Balashova’s main project was designing a new building to house a local cultural centre. Her fate would soon change, however, probably because she was the only architect at the company. “One day I got a phone call from a very important man, Konstantin Feoktistov, an engineer and cosmonaut. He said that Sergei Korolev was developing a housing module for the new Soyuz spacecraft, in which astronauts would spend several weeks or even months. The initial capsules measured about 2-3 cubic metres, with only enough room to lie in. Cosmonauts were only given two red cases for their equipment, and power strips to charge devices. Korolev was extremely upset about this: ‘How can one live in such conditions, especially in space?’” Then he remembered that there was someone at OKB-1 who could make space travel much more endurable.

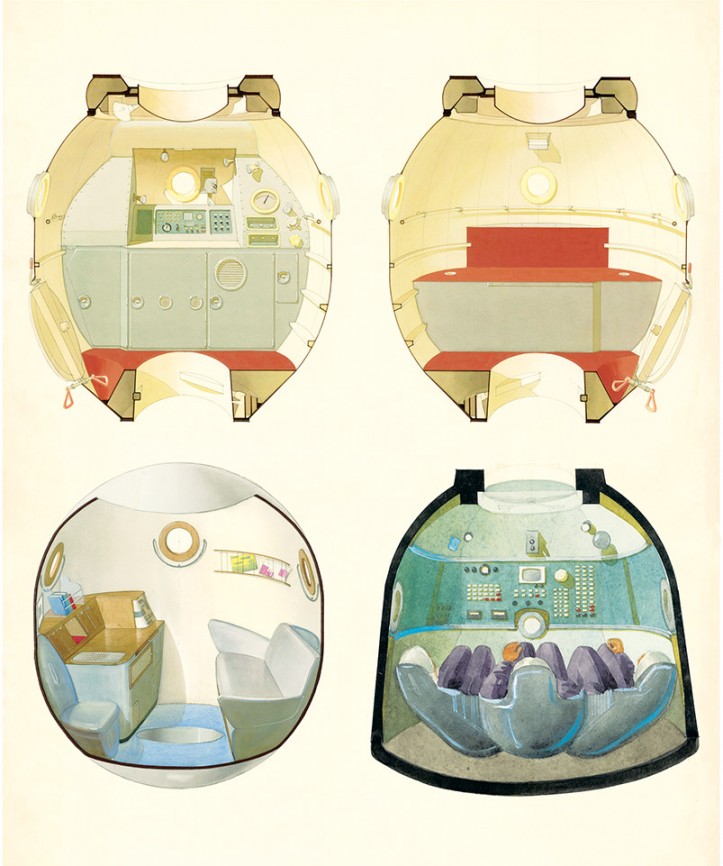

Security requirements prohibited Balashova from entering Feoktistov’s work area, so they would meet on the stairs. “It was just an interior design project for me, like the ones I used to work on at university. The only difference was that this one would be in space! Nobody knew how to approach it. I made my first sketches in the kitchen all through the weekend. I gave them to Feoktistov on Monday, also on the stairs. After a few days, I got the green light from Korolev and they asked me to make a model.”

The two red equipment cases were redesigned. Balashova turned one of them into a cabinet, and the other into a couch. The cabinet was divided into a wardrobe with fittings, areas for storing cans of food and water, personal hygiene items and books – it was also to be used as a desk for work. Next to it, she placed a device with the code name ASU (sanitary disposal unit), a lavatory resembling a small, round chair. The couch was obviously also filled with equipment. “I never spoke to Korolev directly, our contact was always indirect,” recalls Balashova. “Everyone respected him, they knew that they were dealing with someone important. He was very strict, employees were afraid of him and followed the iron discipline he demanded in the workplace.”

From visionaries to engineers

The chairman of RSC Energia was described as an iron man who, at the same time, had the imagination of a 12-year-old boy – he dreamed of travelling to Mars. He had been fascinated with flying and planes since childhood. He was known at the company for his dark humour and his usual saying: “Death without obituary”. He had not escaped the Stalinist repressions of 1937, having experienced the terror of the gulags first-hand. For the first three years, he fought to survive in the polar land of Kolyma, where he drew diagrams of future radio-controlled rockets on the walls of the barracks. Someone noticed his technical talent, so for the next seven years of his sentence he worked at a closed centre, designing ballistic missiles for the Red Army. At the end of the war, he was given the task of building a space programme, and gained Khrushchev’s trust. When the Nobel Committee was deciding who would receive the prize for the first Sputnik, the secretary general of the Communist Party did not reveal the identity of any of the designers and announced that the entire Soviet nation deserved it. Nevertheless, the secret activities of Sergei Korolev and his leading role in the Soviet space programme were well known in the West.

There would have been no technological revolution in the USSR if not for the philosophy known as Russian cosmism, which had begun back in the silver age, in the times of spiritualist séances, occultism and alchemy. One of the first cosmists was a friend of Leo Tolstoy (an enemy of industrialization and technical progress), Nikolai Fyodorov, also known as ‘the Socrates of Moscow’. This philosopher, futurist and ascetic moved in the circles of mystical Orthodoxy, esotericism and pseudoscientific metaphysics. He believed in the progress of civilization (“science comes from God”), but also in the last judgment and resurrection. In his opinion, outer space was needed by humanity so that all resurrected people could be accommodated on neighbouring planets, because there would not be enough room for everyone on Earth.

Fyodorov worked in a Moscow library, where he met the young, hard-of-hearing son of a Polish exile, Konstanty Ciołkowski – a passionate scientist who dreamed of flying and overcoming gravity. Influenced by his older librarian friend, he began to feverishly study physics, mathematics, spherical geometry, astronomy, mechanics and chemistry. Before he developed his theory of aerostats and the first metal airship, he passionately studied the works of Isaac Newton and came into contact with Dmitri Mendeleev. In the science-fiction novel On the Moon, he predicted the conditions on the Earth’s satellite.

The visionary Ciołkowski always stressed that his pioneer theory of rocketry was only a supplement to his philosophical treatises, which are known to only a few, even though he wrote over 400 of them. He had unique views: on the one hand he declared absolute materialism, claiming that the cosmos is simply an ordinary mechanism, albeit an unbelievably complex one; on the other hand, he considered himself a panpsychist, claiming that all matter, animate or inanimate, could feel positive and negative stimuli. He believed that organized dissemination of knowledge throughout the universe is key, but for the time being man is in a transitional stage of evolution. When humanity reaches the next stage, wars and competition will disappear and global justice will prevail. “And then maybe higher civilizations will want to visit our planet. It is possible that at this point no one is trying to visit us, just as we would not go visiting hungry wolves, poisonous snakes or mad gorillas. The instinct to kill or torture cannot be a characteristic of the higher forms of existence,” he wrote. Shortly before his death in 1935, he was asked to act as a consultant on the film Cosmic Voyage. The film’s creators envisaged that the first space flight would take place in 1946. At that time, no one could have predicted the outbreak of such a terrible war and the fact that rockets would be used to serve a completely different purpose than the ‘organized dissemination of knowledge’.

Antigravity architecture

“In the Soviet Union, hardcore conformism has always lived in harmony with the boldest visionary avant-garde,” Frederic Chaubin wrote in the introduction to his book Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed, published by Taschen in 2011 and devoted to the brutalist space-themed architecture of the USSR. Initially, Galina Balashova had to fight for her own artistic vision against people like Konstantin Feoktistov, who once cynically stated that “cosmonauts would even fly in a tinned can for that kind of money.” “We weren’t really concerned with comfort,” recalls Leonid Gorshkov, one of the designers from OKB-1, in a television documentary about Balashova. “We were very surprised when we learned that cosmonauts needed time off, or a moment to themselves, just like the rest of us.”

“Korolev liked my first model. His only suggestion was: the interior should look more modern!”, Balashova recalls. “Feoktistov, on the other hand, simply considered my ideas to be indulgences. When we met again on the stairs, he told me straight out that he was only working on my project to appease his supervisor. He said that my role in the company was unnecessary. He considered interior design unimportant. He thought the artist Viktor Dumin, who used to paint the exteriors of the rockets, was enough.”

Korolev always had the last word, however, so Balashova was allowed to begin working on the details of the new Soyuz craft: nets, rails, fixings. The biggest challenge was the lack of gravity and limited spherical space. It was not clear yet how cosmonauts would sleep, eat, and use the toilet. “I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to fit it all in – the equipment had to be kept to a minimum. The architecture of antigravity is governed by completely different laws, and I had to make quick decisions. It was fascinating!”, says Balashova. “After all, most of the corners in earthly buildings are straight angles, whereas here I was dealing with curves. I had to determine where the floor was, where the ceiling was, so I created a special colour code. It was simple: the lower, the darker; the higher, the lighter.” The metal Soyuz framework was covered with a non-toxic soft material, polyamide (P56P) produced in Kiev. For interior colours, Balashova used lighter shades of green, yellow and blue. Thanks to the many electrical circuits present, it was possible to design displays to facilitate orientation. The bright interior was illuminated with a gentle light, giving a feeling of cosiness, and the entire construction resembled images out of cult science-fiction films.

The cosmonauts were mostly concerned with practical issues, such as keeping items from flying around the ‘room’. Balashova introduced a system of Velcro strips. They were attached to almost everything, from food cans to camera film boxes, cables and other devices. Thanks to this, they could be easily attached to the surfaces of walls and furniture. Velcro was also attached to the surface of the seats, and the cosmonauts’ suits had bonding material sewn onto them, so that they didn’t float off. During the first Soyuz expedition, however, it was noticed that this material was too strong and it was difficult to peel off of the couch. “The trousers had simple elastic waistbands and as a result, the cosmonauts, upon getting up in the morning, would simply float out of them. Later, several crew members complained about it and I had to change the material,” says Balashova. In the next model, Soyuzie-19, the couches had straps attached, similar to those used today on passenger planes.

“In general, I tested everything myself. I would go inside the modules before the flight, fasten the items, lie down. But I could not check for myself how it worked without gravity. After each expedition, I always asked if anything needed to be changed. I had to adjust the toilet as it wasn’t attached very well. The sleeping spaces were not ideal either. Documents for entering flight data needed to be available and ready to be filled out at all times, but they also needed to be firmly attached to fixed surfaces. The cosmonauts also asked for special mosquito nets to protect against flying particles, crumbs and dust.”

The interior lining was made of special fire-resistant artificial leather and anti-glare glaze. Balashova was responsible for choosing the colours and raw materials, for which she would travel to various factories. “I was advised to go to the city of Tver, which at that time was called Kalinin. There was a factory there which made hunting outfits for Khrushchev. A new kind of fabric was created there – a foam-rubber substitute for silk and wool. In those days, it was considered state-of-the-art.”

Feoktistov still stubbornly claimed that Balashova’s approach was too novel and that it all looked “too foreign”. The atmosphere at work was getting worse. The cosmic designer had no family connections or influential contacts within the party. She was paid a minimum salary and worked on the Soyuz after hours as a ‘volunteer’. “At that time, it bothered me that I was not considered part of the team. At Energia, the designers were all men, while women worked in the background. But from today’s point of view, I think it was a privilege to be able to work independently like that, which was unheard of in those days. I could follow my own creative path, as I had been taught at the MArchI institute. Most engineers didn’t really understand my role anyway.

“They weren’t passionate about their jobs, didn’t put their hearts into it. To them, I was just some woman playing around with colours. And I was racking my brain trying to figure out how to ergonomically fit various sized devices into spherical shapes, like some task for pre-schoolers. I had to explain these basic things to those supposedly super-smart men: that architects not only build houses, but they can also design the internal spaces of planes, ships and other objects. For engineers, the relationship between man and machine did not matter much, yet they always had the last word, and Korolev had more serious issues to deal with. But because the spacecraft needed to become lighter, in time I gained the builders’ respect – they would show me their ever-smaller metal hulls with a questioning look: how can we fit everything inside?”

Another project on which Balashova was invited to work was called LOK (Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl), or the Lunar Orbital Craft. For this project, she was officially appointed engineer. There was a mad race on with the Americans, so they had to work fast. In LOK, they didn’t even have a conventional floor or ceiling; the only points of reference were two small chairs. Colours, which were to distinguish the top from the bottom, were therefore of fundamental importance. The craft was completed, but it never took off. In 1969, Neil Armstrong planted an American flag on the moon’s surface. The project was scrapped, and the LOK model was thrown in the trash.

Burning landscapes

Balashova’s cosmic-themed watercolour adventure began purely by accident, or perhaps the absurd Kafkaesque Soviet bureaucracy had something to do with it. Everyone at Energia followed Sergei Korolev’s orders to a tee. When the boss demanded that the spacecraft’s interiors should look more contemporary, Balashova designed more cosy spaces in lighter tones. On one of the sketches, she drew a picture between the books in the cabinet. It was not any specific picture; rather a conventional, casual detail intended to warm up the housing space. Korolev approved the draft, and the project was ready to be made a reality. And so Balashova began painting pictures. It was not a chore to her, quite the contrary: painting watercolours was still her favourite pastime. From then on, it became a tradition – each space flight had to have a different painting on board. “These were landscapes of my hometown at different times of the year. Winter in the garden in Lobna, the view from my window in Podlipki, a small river in the Yaroslavl Oblast. There were also warmer landscapes, a sunny beach on the Black Sea in Sudak in Crimea, where I spent holidays with my parents. Wherever I went, I painted watercolours,” Balashova recalls in Meuser’s book. The author himself writes in the preface: “I first saw her cosmic sketches, only later did I discover the landscapes and still-lifes. Perhaps these paintings wouldn’t be so special if it were not for their special context. They were saturated with colours and brightness because they were painted for people who would not see sunlight.”

Watercolours were more than just a hobby for Balashova; she spent whatever free time she had left on them. Once her daughter was born, there was even less free time. She would hang her paintings at home or give them away to friends, but she couldn’t have imagined in her wildest dreams where some of them would one day end up. “The paintings that flew into space are gone. They got destroyed along with each housing module. On coming back to Earth, only the capsule returns, the rest burns up in the atmosphere. Each of these paintings is etched in my memory, just as they remain in the memories of the cosmonauts who flew with them. They helped them endure their separation from Earth.” Balashova felt fulfilled as an artist, designer and therapist: “What they wanted was sunlight, greenery and water, no dark colours. Water was the most important. It calms you down. The spacecraft began to look like art galleries.” Not all of the paintings, however, were turned to ashes. One of the cosmonauts smuggled several of them back to Earth underneath his spacesuit.

Piracy on a cosmic scale

A turning point in Balashova’s career came with her participation in the first international space project. The icy relations of the Cold War era had begun to temporarily thaw and in 1972 the two world superpowers were preparing for a joint space expedition. It was three years before the Soyuz and Apollo crews, each setting out from different hemispheres, met in space. At Energia, meanwhile, a new spatial concept for the Soviet spaceship was being developed. The level of comfort afforded by the module became a matter of state importance, because it would host American astronauts. In addition, it was the first flight that was to be broadcast on television around the world. The housing areas would be filmed around the clock, so they had to look good and functional, and they had to be well-lit. It was also necessary to fit photographic, film and lighting equipment somewhere on board.

In 1973, Balashova finally began working in the project planning sector. Responding to the needs of television, she selected various shades of light colours, dominated by green. She avoided using red, one of the country’s official colours, because it would appear black on black-and-white screens. Television cameras were attached to a special handrail. To prevent unwanted glare, the surfaces inside the module were covered with matte glaze.

At RSC Energia, Balashova’s work was no longer mocked as ‘whimsical design-stuff’ – work was underway to prepare for the Aersalon, an international exhibition at the French Le Bourget. Good thing that the ‘colour lady’ was always nearby.

Balashova designed the logo of the Soyuz-Apollo project; it was concise and minimalist. “Adding anything to it would be unnecessary. It resembles the symbol of infinity with our planet in the middle,” wrote the foreign press, quite impressed. They loved the logo at NASA. The exhibition at Le Bourget took place in 1975. The famous logo became the venue’s trademark and Balashova’s greatest success, but she had to remain incognito. “I was not allowed to sign any external documents from outside the company,” she recalls with a tinge of regret. “I was told: ‘Gala, draw something’, so I drew. Only our superiors went to the exhibitions, whereas we were just anonymous workers.”

At the Souvenir Factory in the neighbouring town of Mytishchi, over 100,000 buttons were produced for the exhibition in France. Balashova signed her only ever contract with the factory and received a symbolic payment, which she used to buy ‘Bear in the North’ sweets for her Energia colleagues. She would soon come to bitterly regret this contract as an “unwitting move”.

After the exhibition, the logo began to be sold and distributed in about 40 countries around the world. It could be seen on stamps, plates and mugs; sweet wrappers, perfumes and cigarettes. The logo’s success encouraged the Soviets to patent it in Switzerland, but patent registration turned out to cost several thousand dollars and no institution in the USSR could afford such an amount on such a trivial matter. The anonymity of the logo’s designer stirred up all kinds of rumours, including that it was the Americans who were really behind the logo, so at the last moment new patches were created and Balashova’s were taken off of the spacesuits. Seeing this confused the American astronauts, who removed them as well. All that was left for Balashova was the thought that the astronauts appreciated the warm interior design of the Soyuz. Supposedly they were amazed, saying: “You’ve made yourself a great looking TV studio here!”

Another scandal was the leak of information on Balashova’s design, due to her unfortunate contract with the Souvenir Factory. Concerned with the logo being pirated, the factory wrote a letter to the copyright agency, which in turn contacted the Soviet Intercosmos programme. Subsequent letters were sent to the Ministry of Defence, and then to the engineer Konstantin Buszyev who headed the Soyuz-Apollo programme. “I was immediately summoned to Bushyev’s office,” says Balashova. “He shouted at me: ‘Who gave you the right to sign a contract in your own name?’ He threatened me with eight years’ imprisonment for allegedly revealing a state secret. I explained that it was not me who had leaked the information, but the factory in Mytishchi. My husband asked me not to cause any trouble and just do whatever they told me to do. So I signed a document in which I waived the rights to my design. That way, my royalties went directly to the company, into the so-called Peace Fund. I didn’t really mind as I didn’t really care about the money. Serving people and humanity were always more important to me than making a profit.”

As if these humiliations weren’t enough, a self-proclaimed author of the logo suddenly appeared in the American press, a certain Robert McCall. “God bless him,” Balashova laughs good-naturedly in a television programme made by TV Kultura. “I have a few more anecdotes on the subject. At that time, my mother worked at the Sheremetyevo airport and told me how containers of unknown origin with my logo on them arrived in the transit area! There were drugs inside them. The logo was often placed on cargo so as to deceive the border patrol.”

Times were changing, Cold War suspiciousness and military rivalry were again standing in the way of joint scientific projects. It was the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’. Stories of utopia and a better world were best left to science-fiction writers.

Watercolours from Arbat

Balashova still managed to work on the interior of the Buran spacecrafts, which never flew. Her last big project was to be Mir – an international space station for the Soviets and their friends (after the collapse of the Soviet Union, astronauts from the West were also allowed there). Balashova proposed a vertical structure for connecting modules, with the equipment on the bottom and the housing and work areas on top. Windows were to be placed all around to increase the perceived spaciousness. However, the engineers preferred the horizontal version. They argued that it better protected against radiation and would be easier to assemble. The same system was used later in the International Space Station (ISS).

Balashova’s anonymous career was slowly coming to an end, while the Soviet space programme gradually deteriorated, as did the Soviet Union itself. By the 1980s, Balashova was solely designing vympels, or pennants for international space flights. They were made of light aluminium so as not to create additional load on board. “I used the symbols of various countries,” Balashova says in the TV Kultura interview, as she showcases her various designs. “For the Soviet-French mission, I made sure to include the Eiffel Tower, and for a joint expedition with India, an outline of the Taj Mahal.” There was also a vympel from the apogee of the Soviet-Afghan war (in 1988, Afghan astronauts joined one of the international expeditions).

Balashova’s last position before retiring was that of a security guard in the company’s reception area. “As a pensioner, I devoted myself fully to my beloved watercolours. I quickly forgot all my career troubles and humiliations. I thought my work was ‘romantic’, but I felt I was in the lower ranks. Sometimes constructors from OKB-1 would come to me a bit tipsy after hours and ask me to draw their portraits, or caricatures of colleagues to send them as birthday gifts along with beer to their dachas. I didn’t really have much of a say here either. Department directors considered themselves the projects’ sole authors, while their staff who did all the work meant nothing. When I left the company, nobody ever mentioned me.”

The walls in Balashova’s room are filled with landscapes. In the poverty and hunger-filled 1990s, they helped her and her family survive. “Actually, we weren’t doing too bad for those times. I began painting on the Arbat in Moscow. I was paid two or three hundred dollars per painting. It was good money. I even had regular customers!” No one cared about space exploration any more, everyone was just trying to survive day-to-day. Among Balashova’s paintings from that period, there are portraits of children and grandchildren dressed as aristocrats, and 18th-century tsarist Junkers, a bit kitschy. Surrounded by chaos and ugliness, Balashova longed for a momentous, classical and harmonious world. Orthodoxy began to play an important role in her life. In the interview with TV Kultura, Balashova prays to the Holy Virgin as she looks through photos of her space modules: “I have always prayed to Her at important moments in my life when I had to make key decisions.”

Perhaps it was faith, hope and an optimistic outlook on life that helped this anonymous pioneer of space design triumph over the string of misfortunes. She lived to see the times when her talent was finally appreciated and considered art, although not in her own country. “I know nothing about computers, I don’t use them and I don’t know what it’s all about,” says Balashova. “But then I realized what happened. In 1991, my watercolour sketches were displayed at the Architects Association. It was my official farewell from RSC Energia. It included that controversial Soyuz-Apollo logo. I did not have to be incognito any more, and there were no more government secrets as our country was falling apart. One of the architects, Andrei Kaftanov, became interested in my work. He came to see me a few years later and asked for copies of some of them. He took about 20 big rolls that I kept under my bed. Someone later told me that he published them online, collecting funds for a supposedly starving Soviet designer. Of course, I knew nothing about it and didn’t see a penny of that money. But thanks to that, the Germans found me. They published a book of my work, organized two exhibitions, and invited us twice to Germany,” beams the ‘granny from Korolev’.

“My most important task was to incorporate Balashova’s achievements into the wider context of Soviet modernism,” says Philipp Meuser. Fascination with Soviet retro-futurism in the West genuinely surprised Balashova, as it would many other artists of her generation who don’t spend all their time on the internet and thus don’t follow the latest trends. Do most trends have to first go through a Western filter before returning to their native soil? That’s a difficult question. These days, Moscow is experiencing something called GOST-omania (from the acronym GOST, which stands for an abbreviation of the former Soviet quality standard – gosudarstvennyy standart); the trend of returning to Soviet design. 1960s neon signs are experiencing a revival, as are old fonts and designs, and hipsters are collecting devices produced in the USSR.

One of the most popular tourist attractions in Moscow today is the Museum of Cosmonautics, located within the base of a great soaring monument depicting a rocket launch, commonly known as the ‘Impotent Dream’. Here, tourists can view the models of all the spacecraft produced at RSC Energia, including Sputniks and two stuffed dogs, Belka and Strelka. The interiors of the modules and capsules have been upholstered with greenish fabric, you can see couches and cabinets, and one of the capsules even has a painting of an autumn landscape in the Moscow Oblast hanging on the wall. Galina Balashova’s name is nowhere to be found.

Translated from the Polish by Daniel J. Sax