A gifted painter; a resourceful mother who left an unsuccessful marriage and raised her daughters on her own; a scholar who at the age of 53, 100 years before Darwin, travelled to the end of the world and proved that what Aristotle wrote about the life of insects was absolute nonsense.

The year is 1700, Suriname, South America. The lush green of manioc fields, the exuberant vegetation, the fruits of bright colours and intense tastes. It’s hot and humid. The Surinamese rainforest – allied with its mysterious universe of insects, with its thick scramble of trees and bushes – guards most of these Dutch territories like a strong fortification. Anyone who wanders into the middle of this forest risks getting caught in an inescapable trap.

The two women who came here from Amsterdam aren’t afraid. They force their way through the forest wearing European dresses. Their skirts get caught up in roots; the branches entangle their hair or sometimes scratch their cheeks. The skin underneath tightly-fastened corsets is sweaty. They have to be careful so that the insects that bite painfully don’t get under the corsets. At any moment, a snake can slither down from a tree…

They are Maria Sibylla Merian, a painter and botanist, and her daughter Dorothea. Together they trudge through the Surinamese rainforest to sketch insects and plants. They also carry boxes – every once in a while, they manage to collect some larvae. Merian nurtures them later in her home: she feeds them, observes them, makes drawings at each stage of their development. She did this as a little girl in Frankfurt, as a married woman in Nuremberg, as a divorcee in Amsterdam. Now she does it in the kitchen of the house she rents in Paramaribo, the capital city of the Dutch colony Suriname.

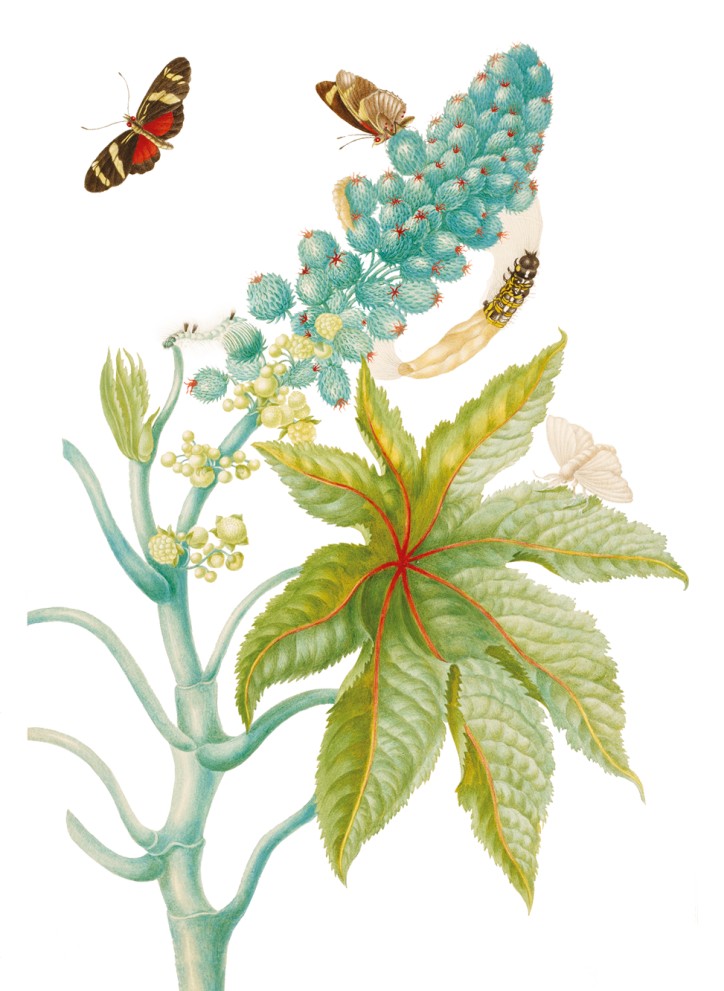

A hairy caterpillar on a yellow pomelo

In 1700, Maria Sibylla Merian is 53 – an elderly lady, according to the norms of the time. Society expects her to knit, sew, and nurse grandchildren. Nothing of the sort for Merian. Instead, she is the mastermind and organizer of a research expedition. She’s enterprising, knowledgeable, brave, incisive, practical. Both Merian and her daughter are pioneers – not only as female travellers, but also as field researchers. 100 years will pass before Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin go on their scientific journeys. In Merian’s time, long journeys mainly involve trade, politics or warfare.

How much energy, curiosity and freedom of mind this incredible woman must have had! The energy is visible in her drawings; their beauty is vivid and full of life. The nature she depicts commands admiration and respect. Merian presents not the garden of Eden, but the fight for survival, as well as the vital force of nature. Here are some plates of her opus magnum, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphoses of the Insects of Suriname). A bright yellow pomelo on which a hairy caterpillar crawls, and around which moths with green stripes fly; a ripening pineapple surrounded by bright red flower petals, with cockroaches in different stages of development walking on its leaves. A flowering branch of a banana tree allows moths of one species to feed; other moths prefer an opened pomegranate fruit. A frog lays eggs under water, beneath a purple-and-blue water hyacinth. A caiman bites a red-and-black false coral snake (Merian saw caimans and piranhas when going down the Suriname River with her daughter, travelling to La Providence, the settlement farthest from the ocean’s shore).

Goodbye to Aristotle

Merian grew up surrounded by art. Her father Matthäus Merian the Elder was a painter and engraver who moved his printing workshop from Basel to Frankfurt, and turned it into a prosperous publishing business. He died when Maria Sibylla was three, so she was raised by her stepfather, the painter Jacob Marrel. It was he who taught her how to paint. Beside beauty, Merian’s drawings have enormous scientific value. She pictured insects and plants not in isolation, but in naturally occurring relationships, showing their life cycles and elements of their ecosystems, thus laying the foundations for biology and ecology. Carl Linnaeus drew from Maria Sibylla Merian’s books when working on his taxonomy. In Merian’s time, it was still believed that – as Aristotle had said – insects were born out of rubbish, dust, or rotten meat and fruit. To finally discard this Aristotelian theory, it took many eggs and larvae fed by Merian with bread soaked in sugar water; many cocoon-hatched butterflies; many transformations and metamorphoses that she observed, painted and described.

She planned to stay in Suriname and work on Metamorphoses for at least five years. In order to get the funds, she sold many of her works and specimens that she had collected. She also received a stipend from the town of Amsterdam (in those days, it was unheard of for a woman to be granted one). Her research was large-scale. Apart from the species of plants and animals that she had been studying and drawing, she discovered many hitherto unknown dyes, which infused her works with unusual colours. Among her informers were native Surinamese women. They told Merian that one of the dyes worked as an abortion medication. The women did not want to give birth to children who would, like them, grow up to live in slavery.

After two years in Suriname, Merian contracted malaria and finally had to go back to Amsterdam. Despite her illness, she worked during the journey and after her return. She hired the best printers to publish Metamorphoses and purchased the thinnest paper. Though it made the quality excellent, it also meant going over budget. In order to cover the production costs, the book was priced expensively, and so did not find many buyers. Merian was undeterred and continued to work ceaselessly. For example, she translated into Latin and Dutch a book that she had written and illustrated long before her Suriname expedition: Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung (The Caterpillars’ Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food).

Nabokov’s delight

On the day of Maria Sibylla Merian’s funeral in 1717, a delegate of the Russian tsar Peter the Great bought many of her watercolours for an art collection in Saint Petersburg. Another hundred works were purchased sometime later by King George III. Merian had corresponded with scientists from all over Europe; many excellent libraries prided themselves on having her books. Her work inspired John James Audubon to create The Birds of America. Goethe admired Merian’s talent for moving between art and science; Vladimir Nabokov, later known for his entomological passion, marvelled at her drawings as a young boy. In the 1980s, her portrait found its way to a 500-mark note in the Federal Republic of Germany.

In Bedtime Stories for Young Rebel Girls, she is positioned next to Maria Skłodowska-Curie. Maria Sibylla Merian certainly deserves her place in the pantheon of inspiring women. She was a pioneer in many fields; courageous enough to follow her talent, convictions and dreams. Her success in achieving her aims, as well as her financial and social independence, can encourage countless female artists, freelancers and scientists of today.

This is all despite the fact that when she was born in 1647, times were bad for women. The suspicion of witchcraft was still a real threat. In 1602, the French lawyer Henri Boguet had published his treatise on eradicating witches – the book was very popular and had multiple editions. Elsewhere, women endured many economic, social and educational limitations.

The family business

Fortunately, Frankfurt am Main, where Merian grew up, was enjoying relative religious tolerance. The family business established after her father’s death was an enclave of free thought. As Kim Todd writes in Chrysalis, a biography of Merian, it was “a safe haven for scientists, religious minorities and visionaries. […] A publishing business served a function similar to a coffee-house long before anyone in Europe was drinking coffee – ink was an equally strong beverage.”

As a young girl, Merian had access to books on natural history, geography, religion and alchemy, as well as the famous history of America Grand Voyages, and the flower almanac Florilegium novum. Her stepfather taught her how to paint. Women were forbidden from studying painting in academies, meaning that only painters’ daughters – such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Angelica Kauffmann – were able to become professional artists. A second group of women who managed to practise art and science were those from wealthy families, including the polymath Anna Maria van Schurman and the painter Rachel Ruysch. Merian did not fall into either of these groups, and thus relied on her own funds for living and research.

Oil paints are not for women

Painters guilds did not allow women to use oil paints; only watercolours. Merian specialized in painting vases of flowers. She was 18 when she married another painter, several years older than her and the apprentice of her stepfather. Soon she gave birth to her first daughter. She juggled jobs as a mother, housewife, scientist and painter. She cooked, cleaned, did the laundry, sewed, and fed the baby; among the pots, stacks of onion and plates on her kitchen table, she kept boxes full of the caterpillars she was studying. Her fellow Dutch naturalist Jan Swammerdam had much more time to think about his research, but Merian equalled him in enthusiasm, and even managed to find the time to paint (and sell her works), as well as teaching others how to draw, thus balancing out the household budget.

Sometime after the wedding she moved with her husband and daughter to Nuremberg, a city that was more close-minded than Frankfurt, with considerably more severe religious and social restrictions. Each social class was required to wear specific clothing. The bonnet worn by Merian outside the home signalled the place that she occupied in the local hierarchy. It wasn’t entirely modest, as she could wear velvet with silk, but any fur accessories or pearls were out of the question. Fortunately, Merian had one important and useful feature: she knew how to establish and keep contacts. In Nuremberg, she befriended the aristocratic Sandrart family, which paved the way to the local society of painters, publishers and nature lovers.

Merian’s first publication was Blumenbuch (The Book of Flowers). “Art and science must embrace and reach out to each other,” she wrote in the introduction. She was still trying to find her own voice, painting flowers in a Chinese vase, marigolds springing from the earth, hyacinths with baroque stems. She wrote her next book (the aforementioned Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung) while still doing research, conversing with nature lovers, reading and walking along the city gardens. Here her style is clearly visible, with insects crawling on flowers, leaves and fruits, or finding shelter inside them.

Out of the cocoon

Her marriage was not a happy one. The German law of the time allowed for divorces, but society marginalized divorced women, in effect denying them any chance of survival. Nevertheless, Merian decided to leave her husband. Barely 30 years old, she (along with her mother and two daughters) moved to a pietist community established by the French mystic Jean de Labadie in the Dutch village of Wiuwert. The rules were strict, especially those pertaining to modesty. Members had to forgo all personal possessions, but Merian managed to keep her painting accessories, and was able to continue her painting and research there.

This secluded period of Merian’s life was a cocoon of sorts, out of which she would emerge a changed person. The key to this metamorphosis lay in the stories told by Labadist missionaries travelling back from the Dutch colony in Suriname, or sending intriguing, exotic specimens of moths and lizards, as well as unusual, aromatic fruits.

The next stop on the route of Maria Sibylla Merian was Amsterdam. The capital of the Dutch Empire was one of the main hubs of industry and science, and a city where women enjoyed relative freedom. They were allowed to do business and earn their own money, whereas in Germany such privileges were unheard of. The Netherlands was the first colonial empire, having bettered Portugal in the spice trade and ruled the seas before England did. In Amsterdam’s markets – beside the ordinary carrots and fish – one could buy oranges, pepper, coffee, cinnamon and nutmeg. Smells and flavours blended in the air as people spoke in Portuguese, Turkish, Danish and many other languages. Dutch ships imported shells, insects and plants that were rumoured to cure all diseases. Everything ended up in cabinets of curiosities and the private gardens of wealthy collectors. Merian was friends with the anatomy professor and botanist Frederik Ruysch and with the famous Agnes Block, in whose garden she saw her first ever pineapple fruit.

The window is always open

Merian shared Amsterdam’s prosperity. In the thick of all the action, she was able to sell her works, earn good money and study. The city invited people to enjoy its abundance, but also acted as an inspiration to move forward. Merian saw many exotic moths and butterflies in cabinets of curiosity. They fascinated her, but they were dead; outside of the ecosystems that were so interesting to her. Suriname, about which she had heard so much with the Labadites, was still calling. In order to raise money for the great journey, she decided in 1699 to sell 255 of her works. Before Merian embarked with her daughter on a ship to Suriname, she drew up her last will. One chapter had closed, another one was just opening.

Merian’s biographer Kim Todd notices that even in the most intimate of paintings created in Delft by Johannes Vermeer – several decades before Merian came to Amsterdam – the seductive presence of other continents is always present. Behind women contemplating a love letter or behind a glass of wine, we can see maps, globes or oriental rugs. The window, through which the famous Vermeerian light seeps in, is usually open. Maria Sibylla Merian could well have been a character in one of those paintings. In deciding to travel to Suriname, “she peered out Vermeer’s glowing window, drank the wine, went out the door, and stepped off the map.”

Translated from the Polish by Jan Dzierzgowski