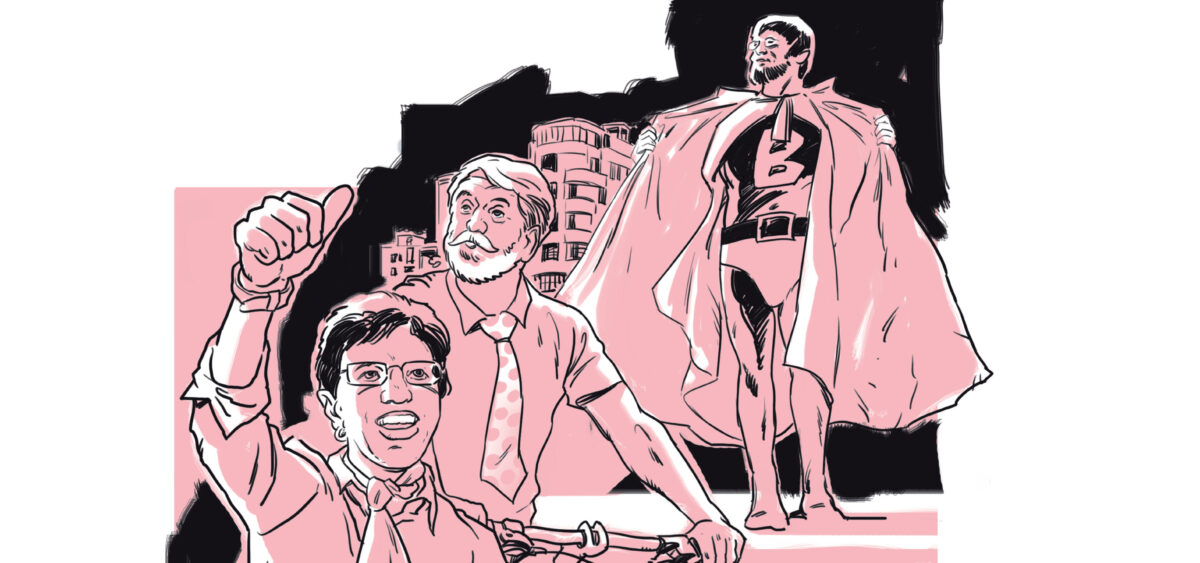

Can a superman, imaginative cyclist and fearless journalist make a revolution? Yes, but it will be a peaceful revolution. Its victim will be violence; its beneficiary – the capital of Colombia, fortunate to have great mayors.

On Sundays around noon, Bogotá doesn’t look like other big South American cities. In the streets of Colombia’s capital, with its eight-million population, commerce is flourishing. Some people are dancing; some are barbecuing. Older inhabitants are playing chess. The younger ones are betting at guinea pig racings. Yoga lovers are practising on the asphalt roads, right next to aerobics enthusiasts. You can spot some theatre troupes, clowns and jugglers, but mainly the cyclists. There are also skateboarders, scooter riders, runners, and people on wheelchairs, but no cars! This event is called ciclovía: a true celebration of cycling. Each Sunday, between 7am and 2pm, the mayor of Bogotá closes most of the main roads, i.e. nearly 300 kilometres. Sometimes, there are altogether 1.7 million eco-friendly single-track vehicles on the roads at the same time. This is a world record – nowhere else is the Critical Mass bike ride so popular.

It is hard to believe that 25 years ago, Bogotá – located in the Andes, at 2650m above sea level – was considered a fallen city. Tourists were afraid to go there (and to Colombia in general) and homicide rates were shockingly high. Socio-political life was dominated by corruption and violence. Many districts, especially the poorest ones, were controlled by gangs, and the inept, corrupt and intimidated police were too frightened to intervene. Those problems were exacerbated by the more than 50-year-long bloody civil war with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Kidnappings for ransom and large-scale drug trafficking were part of everyday life. In the selva – the Amazon rainforest – guerrillas kept people locked up in concentration camps for many years. Although Bogotá was rarely at the centre of events, it also witnessed some tragedies. In 2003, guerrillas perpetrated the bombing in the capital’s elite El Nogal Club, popular with businessmen. Dozens were killed.

Compared with other South American countries, Colombia was the place that people tended to avoid. Airlines cancelled their flights. Large companies withdrew investments. The country fell into chaos. Presidential candidates and activists committed to fighting corruption and lawlessness were assassinated one by one. Apart from the helplessness of the government, the country was also struggling with major economic problems and enormous social inequalities. Only a tiny fraction of those in power, including cocaine barons and guerrilla commanders, were getting rich. Most people were doomed.

In the last 25 years, however, Bogotá has become the epicentre of unprecedented changes. This is where a truly ‘positivist’ revolution was carried out by some real heroes, or rather – superheroes.

The world’s cycling capital

Ciclovía first took place in Bogotá in the mid-1970s, but it turned into a mass event between 1998 and 2000, when the Washington-born Enrique Peñalosa was mayor. The brains behind this project was his brother Gil Peñalosa, at the time the Head of the Parks, Sports and Recreation Department at Bogotá’s city hall. It was Gil who started to promote in Colombia the idea of a healthy lifestyle and a modern, people-friendly city. It was also thanks to him that the no-traffic zone on Sundays was significantly expanded (from 10 to 300 kilometres of roads), and ciclovía became a large-scale, well organized event. Gil Peñalosa later moved to Canada, where he made his name as the founder of the international non-profit organization 8-80 Cities, as well as a visionary and community engagement expert. Today, he advises decision-makers all over other world on how to develop cities that are free from discrimination based on gender, age, nationality and medical conditions. He designs urban spaces and thinks that modern smart cities bring people together.

As he argues, “green areas improve our quality of life. They’re conducive to socializing and physical activity. They also serve as playgrounds for kids, where they acquire basic skills. Each inhabitant should have a park within a short walking distance from their house. This radically transforms social relationships and makes people happier. Such green solutions will work in every city and every country.”

Gil Peñalosa’s brother, Enrique, also implemented the above ideas when he became the mayor of Bogotá in the late 1990s. Once he kick-started ciclovía, he developed the Cicloruta: a system of modern, two-way cycling lanes running alongside main roads. Now those who could afford a car were also switching to this cost-effective and healthy means of transport. At first, Cicloruta stirred a lot of controversy – the lanes were running outside many private houses and on private pavements. The owners weren’t usually asked for permission or offered any compensation. In consequence, protests broke out and the lanes were blocked. Fortunately, the issue was resolved and the renewed popularity of bike-riding gave rise to the new success of Colombian cyclists.

This was a big deal since cycling, next to football, is considered a Colombian national sport. The achievements of Nairo Quintana, Rigoberto Urán and Egan Bernal (the winner of the 2019 Tour de France) only prove it. These famous sportsmen, however, need to patiently wait to enter into the national mythology, since Colombians still worship their champions from the 1980s: “Lucho” Herrera and Fabio Parra. Excellent at high mountains routes in France and Italy, they were both excitedly supported by the whole country during television broadcasts. In 2000, FARC guerrillas took advantage of Herrera’s fame and kidnapped him (like many other important people at that time). Thankfully, after 24 hours the retired cyclist safely returned home. Guerrillas knew that detaining him longer would have been bad for them since Colombians worship their cyclists like national heroes.

The ticket to a better city

Some of Peñalosa’s other daring ideas also stirred controversy. One fine example is Pico y placa (Spanish for ‘Peak and Plate’). According to this scheme, on selected days during morning and afternoon peak hours, traffic access to urban areas is restricted to vehicles with license plate numbers ending in certain digits. Non-compliance with this rule results in a heavy fine or a vehicle being towed away.

To further reduce traffic congestion, a ban on parking on pavements was introduced in central districts. Although the drivers were going mad, the city would consistently put traffic cones on pavements to prevent them from parking there. At the same time, illegal trade was eliminated from squares and streets. Within a short time, car traffic was reduced by 60%, and inhabitants switched to buses, private minibuses and bikes, whose popularity was growing. Peñalosa’s idea was further developed by his successors and adopted by other cities – not only in Colombia, but also in Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru.

Bogotáns will also associate Peñalosa with the famous TransMilenio: a bus rapid transit system introduced in 2000 (hence the name). It was modelled after Rede Integrada de Transporte, an integrated transportation network in Curitiba in Brazil. Although it isn’t free from flaws, it has served as a sort of a substitute for the metro to this day. In place of trains, there are articulated TransMilenio buses that run through the metropolis via a specially dedicated lane. Stops resemble metro stations: they’re roofed and fenced off. Vehicles park only in assigned spaces; there are automated shields made of safety glass on the platforms. Passengers enter the station through the gates and use smart city cards.

But this was only the beginning; Peñalosa’s revolution wasn’t limited to the transportation system. Together with activists, artists, architects and designers, he also initiated other schemes. The exclusive Country Club of Bogotá in Usaquén district, where previously only the rich would hang out, became open to all – a large park was built there. 200 other unused green areas were redeveloped in a similar way. Green squares were created around buildings and a 113-hectare metropolitan park named after Simón Bolívar was built. Many modern libraries and schools were opened in slums areas, too.

Inspired by these changes, Sergio Fajardo and Alfonso Salazar – the mayors of Medellín, Colombia’s second biggest city – implemented similar solutions there at the turn of the 21st century. They managed to attract international investment and new technologies. The crime rate fell significantly. The city’s finances became more transparent, while access to education and culture became much easier. In slums, apart from schools and libraries, a new infrastructure was developed. One notable example is the infamous Comuna Trece district. In 2011, a giant outdoor escalator was built on its steep hills and a massive water curtain, useful in hot weather, was installed. The district, isolated before, finally became connected to the city centre via a Metrocable – a gondola lift system integrated into the Medellín Metro. Thus, Medellín, which in the 1990s was considered by Americans “the city of crime and fear”, in 2012 was hailed by Urban Land Institute and Wall Street Journal as “the world’s most innovative city.”

Enrique Peñalosa was recognized internationally. A number of renowned institutions, including New York University’s research centre, rewarded his achievements in sustainable development and smart city planning. In 2015, Bogotáns re-elected him as their mayor. Today, Peñalosa is regarded as a global icon in modern city management and a guru for many urban activists.

Mimes instead of policemen

Peñalosa’s predecessor (and then successor) as the mayor of Bogotá was Antanas Mockus Šivickas. He served two terms: first in the years 1995–1997 and then in 2001–2003. When Mockus was in office, Bogotáns could witness how Plato’s idea of the city governed by a sage-philosopher somehow materializes itself. Mockus was born to a family of Lithuanian immigrants. He has a degree in Maths and Philosophy, and before taking office, he had been the Rector of the National University of Colombia. When Mockus was mayor, city management evolved into a great spectacle.

Mockus’s main goal was to fight violence. With his penchant for philosophy, he perorated about the significance of grassroots work in eradicating violent behaviour. Although Colombians had a rather low opinion of their neighbours, they were soon to change it. What actions needed to be taken? A domestic violence hotline was launched, for example, and the ley zanahoria – the ‘carrot law’, according to which bars had to close before 1am – was passed. Statistics revealed that most crimes in Bogotá were committed between 1am and 4am, and that perpetrators would drink in bars beforehand. Mockus, who personally checked whether bars enforced those laws, was at first the object of mockery. This stopped, however, when a drop in homicides at weekends and drunk driving crashes at night was observed. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this campaign, Mockus invited his co-workers and city inhabitants to a cemetery. A few hundred people lay down in graves and then symbolically came back to life. “These are the ones whom we saved,” the mayor declared.

There was also another pacifist initiative that received a great deal of publicity. In February 1995, Mockus’s security guards placed guns in a coffin. The mayor himself stood right next to it, dressed in a bullet-proof vest with a heart-shaped hole cut in the centre. This was the reaction to the death of his friend whom FARC guerrillas had shot while they were stealing cattle. Mockus publicly called on guerrilla commander Manuel Marulanda to ask Colombians for forgiveness. This marked the beginning of a large-scale campaign. In violence-plagued Bogotá, the mayor encouraged people to get rid of guns. For each disposed gun, he offered a gift. In his office, he placed a punch bag with the slogan: “Vent your anger here and think more clearly.” Mockus admitted to using it often himself.

Later, he launched the “vaccines against violence” campaign. During street events, people drew portraits of their enemies on balloons, which they would then pierce. Mockus also took part in it, drawing the teacher who abused him in childhood. The mayor also ran around the city in a Superman costume, with the cape in the colours of Bogotá’s flag. He was trying to convince people that everyone is endowed with the power to do something for their community. He named himself Supercivico – a Supercitizen.

Thanks to Mockus, 420 mimes showed up in the streets of Bogotá. They would stand at intersections, showing drivers either a white or red card – for good or bad driving respectively. If a car parked on a zebra crossing, the mime would pretend to push it back. “If the red light can change, we can change too,” read one of the campaign’s placards. Mimes also educated pedestrians by performing risky jaywalking scenes, and by drawing stars in fatal crashes zones. Mockus also waged a war on corrupt policeman from the traffic department. During one of his terms as a mayor, over 2000 policemen were fired and those who replaced them were obligated to cooperate with the mimes. Almost instantly, the number of road accident fatalities fell by half. Over the next few years, people would keep showing each other white and red cards.

The provost’s naked buttocks

Another successful campaign was aimed at reducing water consumption. One of the TV stations ran a story about Mockus’s showering habits. They showed the mayor covering his buttocks only with a part of the round gourd of the calabash tree. He would turn the tap off while soaping or scrubbing his body, and turn it back on only to wash out quickly. It worked: water consumption was reduced by 40%.

Mockus had already proved to be an exceptional performer before he became the mayor. In 1993, he barged into the office of César Gaviria, the then president of Colombia, armed with a pink plastic sword. He demanded a serious conversation about violence in the country. When Mockus was the professor and provost of National University, during a heated debate he (in)famously showed the students… his naked buttocks. As he later explained, they wouldn’t let him speak, hurled abuse and booed him, which is why he decided to step out of the professor’s role. He achieved the desired effect: the students fell silent. Academia, however, disapproved of his performance. In the aftermath of scandal, he had to resign. He resorted to using his buttocks as a weapon two more times, though.

Not everyone was a fan of his peculiar tactic, but the numbers were on his side. Between 1994–2003, the crime rate in Bogotá declined by nearly 75%. During the same period, the number of kidnappings became eight times lower while bank robberies were 27 times lower!

Some time ago, I decided to walk the National University’s campus in the footsteps of Mockus. Other graduates of NU included the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature Gabriel García Márquez, South America’s most famous painter Fernando Botero, and the “tribune of the people” and one of the most renowned Colombians in history, Jorge Eliécer Gaitá. His 1948 assassination led to the outbreak of civil wars. Between 1936 and 1937, Gaitán also served as a mayor of Bogotá. I was looking at the university’s buildings. A huge mural on one of them depicted a labourer in a red scarf militantly raising his clenched fist, as well as a girl in a blue helmet shouting: “Rise up and fight!” But the highlight of this mural was Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who was saying: “I hope to wake up one day and see my people united around true peace.” His image was accompanied by the symbols of left-wing organizations.

While walking around the campus and reminiscing about Mockus’s performances, it was easier for me to understand why one of his successors was Gustavo Petro, who as young man was a member of the radical left-wing guerrillas M-19, considered across the world a terrorist organization. He wasn’t any worse than his outstanding predecessors. On the contrary, he did a lot for the city.

An imaginative terrorist

Colombians remember M-19 as those who ran many spectacular campaigns, or rather ‘happenings’, aimed at helping the poor. Its members had quite vivid imaginations – they would, for instance, hijack milk cisterns or poultry trucks, and drive to the slums to distribute food and drinks to the people. They’re also known for stealing the sabre of Colombia’s national hero Símon Bólivar from his house/museum in Bogotá. This was a symbolic act, which supposedly inspired Mockus. One of the most spectacular things M-19 did, however, was construct an underground passage, which they were building for many months. It enabled them to steal over 5000 guns from Colombia’s largest military warehouse: Canton Norte in Bogotá. Gustavo Petro joined the guerrillas in 1977, when he was only 17, and received the nom-du-guerre “Aureliano”, after one of the characters in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Eight years later, he got arrested for the illegal possession of arms and plotting against the government. He spent a year and a half in prison, where he was tortured and starved. When in 1988 the city guerrillas evolved into the political party Alianza Democrática M-19, based on an agreement with the government, Petro became one of its leaders. In 1991, he was elected as a member of the national congress, and later as a senator. He also ran for the presidential office twice.

He was the mayor of Bogotá between 2012 and 2015, making his name as an advocate of the rights of minorities and the discriminated. He inaugurated the LGBTI Citizenship Centre, the Women’s Secretariat – whose role was to eliminate gender-based social inequalities – and a network of birth control and abortion care centres. He found money to build 417 new kindergartens and supported many pro-environmental initiatives. In the face of global warming, he passed laws protecting the wetlands and encouraged water saving. He was active in other fields too. For instance, he radically restricted gun carrying in public places. As a result, during his term the homicide rate was the lowest in 20 years. Petro also wanted to ban the bull fights on the famous Plaza de Toros de Santamaría in Bogotá, but the Constitutional Court of Colombia opposed this idea. In 2018, when his term was completed, he ran for president once again. With eight million votes, he got to the second round. His successor as mayor was Enrique Peñalosa, whom Bogotáns already knew very well.

The day of the woman

On 1st January 2020, Claudia López, another extraordinary person, was sworn in as mayor of Bogotá. 50-year-old Lopez is a Green Alliance activist and former senator.

“This is the day of the woman. Bogotá has overcome machismo and homophobia. It’s one small stop for me, but a giant leap for Colombian women,” she said in her victory speech and passionately kissed senator Angélika Lozano, her then fiancée and now wife. López is the first female mayor of Bogotá and the first openly homosexual person in Latin America to hold this office. She won the vote of young liberal Bogotáns, who over the last few years have admired her uncompromising attitude.

López gained popularity over a decade ago, when she was working as an investigative journalist for the influential Colombian media. She exposed major political scandals, corruption, the involvement of politicians in shady business and their links with the criminal world. This was when she antagonized the omnipotent Álvaro Uribe, president of Colombia between 2002 and 2010. In a televised debate, she accused Uribe of supporting paramilitaries – the right-wing militias charged with homicide, extortion and drug trafficking. For years, she had to face Uribe and many other politicians, both in court and everyday life. She was threatened with death, and forced to emigrate for some time. But as she admits today, this only made her stronger.

López comes from a modest background. Her family was large and like many children in Bogotá she had to take care of herself. To receive education, she relied on scholarships and loans, which she was then paying off for years. She holds a degree in Finance, Government and International Relations from Universidad Externado de Colombia, and she graduated from New York’s Columbia University with a Master’s degree in Public Administration and Urban Politics. In the US, she also did her PhD in Political Science. As a teenager, however, she didn’t dream of being a politician. Actually, she almost became a medical doctor educated in… Poland. In 1990, she was offered a scholarship from the Medical University of Warsaw, but as she was packing her bags, the Polish government withdrew the offer for financial reasons.

López has been part of big politics for six years. She gained her first experience in government administration in the late 1990s, when she was in charge of social issues at Mayor Peñalosa’s office. Although they grew distant over the years, after winning the elections she said: “Enrique Peñalosa was my friend, teacher and mentor. I learned a lot from him.” She summarized her plan for Bogotá in the following way: “We have nothing to lose and everything to gain. We have the planet to save. We need to save democracy. Future generations will hold us accountable.”

The future will show how many of her ambitious plans are implemented. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, her popularity is growing. Bogotáns speak favourably of her quick response to crisis. To reduce the number of infections in public transportation and improve the quality of air, an additional 47 kilometres of Cicloruta were built almost overnight. The cycling lanes in Bogotá now amount to 600 kilometres.

The city finally belongs to us

Run by great mayors, Bogotá has rewritten its history. Today, it is a modern, vibrant metropolis – a model of innovation for the richest cities in Europe and the US. Bogotá is a city agglomeration associated with ongoing change. And for nearly three decades, it has been associated with change for the better.

Yet this doesn’t mean that it has successfully tackled all its problems. There is still a marked division between the rich northern districts and the poor southern ones. In the former, there are luxurious shopping malls, glass skyscrapers and chain cafes; in the latter – run-down brick buildings, homeless people and higher crime rates. Thanks to the decisions taken by the mayors, however, those inequalities have been reduced and Bogotá has become one of the few capitals where the richest co-sponsor the everyday life of the poorest. The municipal taxation system was reformed in such a way that nearly 350,000 inhabitants of the most affluent districts chip in for the better lives of the seven million who live in extreme poverty, often without electricity or water.

Why did such daring experiments work out specifically in Bogotá? There is no single answer to that, but some compelling theories have been proposed. Armando Silva Téllez – a renowned Colombian philosopher, sociologist and the author of Imaginarios urbanos and Bogotá imaginada (important works in urban studies) – argues that over the last 25 years Bogotá has become an internally consistent ecosystem that replaced a conglomerate of random people from different parts of the country and the world. In the past, Bogotáns didn’t identify with their city. Today, they feel proud of Bogotá and responsible for it. Téllez points out that the 19th-century inhabitants of Bogotá were the descendants of immigrants who were forced to come here and who lived in ethnic and class ghettos. Nowadays, this ‘no man’s land’ has found its people, who feel connected to it. For Téllez, the key to this transformation is the new aesthetics and functions of the public space, as well as new rules of social interaction.

Martha Amorocho, a businesswoman who lost her son in the El Nogal bombing and is now working towards reconciliation, perceives this revolution in a similar way: “We are a society of immigrants who are still assimilating. Violence and rowdiness are in our genes because 500 years ago the country was conquered by criminals, all sorts of brawlers, religious fanatics and unscrupulous people who considered the indigenous inhabitants of this country lesser humans. But today we are both aware of this history and brave enough to talk about it. Experiments of this kind helped us muster courage and finally made us feel ‘at home’.”

Today, Bogotá’s metamorphosis is a model for many cities across the world, as it proves that the most rapid changes can be made if we influence not only people’s behaviour, but also their identity and a sense of dignity. New roads and buildings are not enough. We also need people who love their city.

Translated from the Polish by Joanna Mąkowska