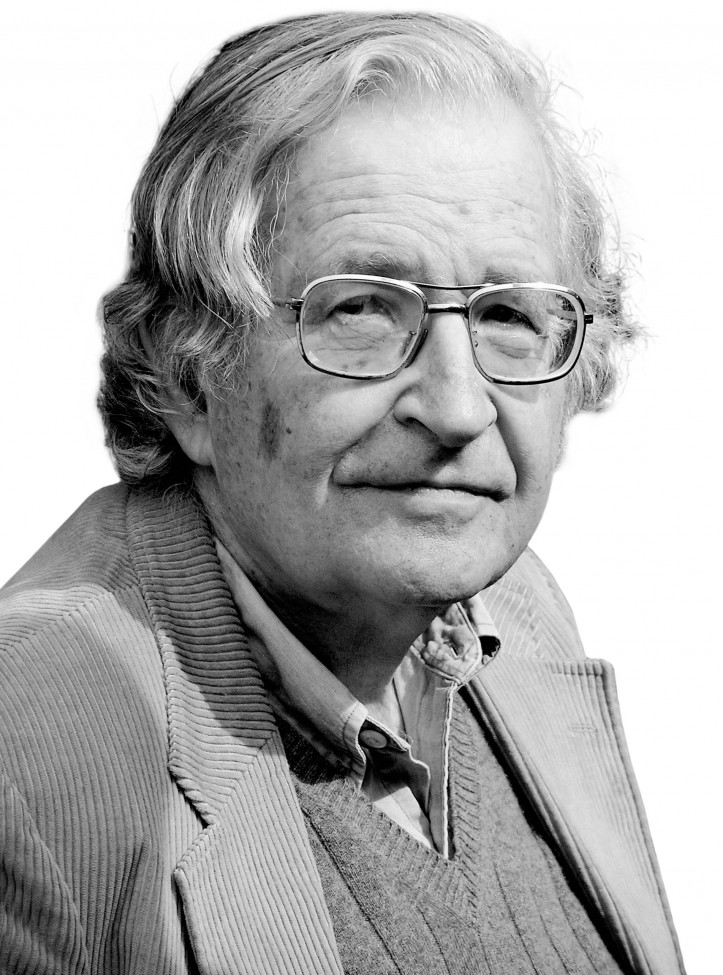

Noam Chomsky talks about who rules the world, the threat of climate change, and the breakdown of global democracy.

Noam Chomsky – a preeminent American thinker, a legend of linguistics, philosophy, and social activism – has turned 90, so he no longer spends much time coining erudite terms or positing highly complex theories. Instead, he speaks in the simplest possible language about the things that matter most. About how the human race is heading for self-destruction, by ignoring climate change. About how the wealthy and powerful get away with everything. About how a sense of powerlessness is propelling people to believe in conspiracy theories. And about how society has nevertheless achieved a lot of good things, and the future of the world is still in our hands… Our very own Tomasz Stawiszyński pays a visit to Noam Chomsky himself.

This interview was conducted in spring 2018.

Everyone who politely inquires about why I came from Warsaw to Tucson, Arizona, knows who Noam Chomsky is – maybe because he has been living in their town for a few years now. The owner of the hotel where I stay, a beautiful villa from 1911, carefully restored and adapted. The waitress at a small Mexican restaurant, her body covered in tattoos and her face festooned with an arrangement of piercings. The cashier in a grocery store, sporting an ever-present smile and giving the impression of being best friends with every customer in line. And so, it seems that the Stevensons are the only people here who have never heard of Chomsky.

Their surname is something they see fit to inform me of immediately, even as we are sitting down to breakfast at the small hotel dining room. John Stevenson, the father; Jane Stevenson, the mother; and Shelly Stevenson, the daughter. They are from Ohio, and came to Arizona to visit their son. “We are the Stevensons!” John chirps proudly in lieu of a hello, and then his whole family proceeds to question me quite inquisitively.

Is it true that Poland is surrounded by a big barbed-wire fence? Is it true that everyone in Poland considers John Paul II to be their greatest hero? Is it true that Russia is set to invade the country and incorporate it into the federation?

When I answer all such questions in the negative, the Stevensons are clearly disappointed. And once I start to talk to them about Chomsky, an outstanding American linguist, radical political activist and analyst, an advocate of anarcho-syndicalism (a political system in which private property does not exist, and all means of production are owned by workers), they lose interest very quickly.

And they start to explain to me that in fact America’s only true hope is… Donald Trump.

“Because he’s a guy who can straighten everything up,” they persuade me. “You see, he isn’t even a politician, really. And politics in America, dear Thomas, is actually just a pile of shit. At least since the times of JFK. If anyone stands a chance of changing anything, it can only be Trump. That’s why they are so afraid of him.”

“They?” I ask.

“Come on, you know who they are,” the Stevensons respond in chorus. “The people who rule the world!”

Hm, I think to myself. Maybe we don’t see eye-to-eye, but at least I have an idea for an opening question.

Tomasz Stawiszyński: Who rules the world?

Noam Chomsky: Are you asking about a specific state?

Not necessarily.

Usually, discussion about world domination refers to states, which states are the most powerful, how they interact, and so on. This has never been really accurate, and in today’s world of neoliberal globalization it’s becoming less and less accurate. So, while the GDP is still measured by individual states, the real question is which corporate structures own the world.

Can the world actually be owned?

A multinational corporation is based somewhere, for instance in the United States, but it operates everywhere. There have been a few studies on ownership in the world economy, with very interesting results. It turns out that the United States places first in just about every category. When you add it all up, it turns out that US-based corporations own about half the world economy. That is a degree of economic power that has never been achieved by any state. Of course, they have intricate networks, where parts are produced in some small factory where the people perhaps don’t even know what they are working on, then assembled somewhere else, with the major profit being made by the parent corporation. What’s that there, on the table?

My iPhone.

Right, a classic example. An American company, but the serious parts were probably made in Japan or Korea, it was assembled in China, then exported to the rest of the globe. But the American company that provides the logo and that profits most from the whole process has its office in Ireland so that it does not pay taxes. That’s the way the world economy is really going.

But states do exist and are doing fine. Moreover, they define the legal framework within which those corporations function.

States are of course extremely powerful and interact with the corporate system in very intimate ways, it’s not easy to delink them, but that network of power is what really rules the world. It’s highly concentrated in the US economy. If you measure purchasing power parity, looking at what you can buy with the equivalent of a dollar everywhere, it turns out China has the biggest economy. Of course, much less per capita, because China has a huge population, so that’s pretty misleading. But what’s required is a much more sophisticated analysis, which has occasionally but rarely been done in a systematic way. So, to get back to your first question, the United States is still overwhelmingly dominant. In some dimensions, for example militarily, there’s not even any comparison; we spend far more and are technologically far more advanced. But even in other domains the US remains an overwhelming economic force.

Does this translate into specific political strength?

China is growing, the EU is potentially powerful, but power is still in US hands. You can see it now when Trump pushes a nationalist line and others have to cave in, they can’t avoid it. Most of these things are not even discussed, they are so obvious. For example, take an issue that’s going to become very significant soon, the P5+1 deal with Iran, which the United States is probably going to terminate [Chomsky’s prediction here soon proved on the mark – ed. note].

P5+1 means the five permanent members of the UN Security Council – China France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States, plus Germany. You mean the deal signed in 2015.

Yes, there is a lot of talk about whether Iran is living up to the agreement. The overwhelming consensus, including from the International Atomic Energy Agency, is that it is. But there is no talk at all about whether the United States is obeying the agreement, which it isn’t – it’s radically violating it. The terms of the agreement explicitly state that the participants may not interfere with Iran’s commercial interactions or block its financial transactions. But this is being done openly, all the time.

Clearly a double standard.

When the US breaks the law, it doesn’t exist. Take the United Nations charter, considered the foundation of modern international law – it bans the threat or use of force in international affairs. The threat of force. What does it mean when the US president and other officials say with regard to Iran and North Korea, “all options are open,” is that the threat of force? When Obama says, we can attack you with nuclear weapons if we like? Suppose some country that had once bombed the United States to oblivion was now sending nuclear-capable bombers to our borders and carrying out threatening military manoeuvres in Canada, would that be the threat of force? We are doing that with respect to North Korea, and everyone thinks it’s fine.

Why is that?

Basically the powerful do what they want. Like the old adage, the Athenian warning to the people of Melos: “The strong do as they want, the weak suffer as they must.” That is what determines who rules the world.

Is this the crisis of democracy that we are hearing about all the time?

There’s a crisis that people talk about. But there’s also a much deeper crisis that, like the United States’ violating laws, is not even discussed. A crisis of liberal democracy is definitely visible in the Visegrad countries – let’s call them illiberal democracies – like in Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and so on. But in Western Europe, too, there is a major crisis of democracy. The EU is structured to be radically undemocratic.

What do you mean?

The major decisions that set the framework within which other governments operate are made in Brussels by an unelected troika: the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the IMF. They set the basic framework; governments have to adapt to it. The troika is pretty much in the hands of the German and other northern banks. The effect of this can be seen in election after election, where the centrist political parties are just dissolving – as in the French or Italian elections, for instance. This is because people are angry, frightened, intimidated, lashing out in all kind of ways, because the control over decisions that matter for their lives are just not in their hands, not even in the hands of their national governments. That’s a crisis of democracy.

There’s talk of such a crisis in the United States as well.

The United States has a different problem. Academic political science in the US has produced quite illuminating analyses of how the system works. They show that the lowest 70% of the population on the income scale are literally disenfranchised. Their own representatives pay no heed to their opinion, but listen instead to their funders and donors, the rich and powerful. When you move up the scale you get a little more influence, but decisions are made at the very top. A major study of Congress recently showed you can predict with astonishing precision the votes of a Congressional representative on major issues simply by looking at campaign funding.

That’s terrible…

And that’s just one part of a whole system of pressures. Take the way legislation is usually written by corporate lobbyists. Corporate lobbyists and lawyers flood the Congressional offices and interact with staff members, they have a lot more information, so they basically write the laws and the representative signs them. Is that democracy?

Is this not a conspiracy theory?

No, if you are a major corporation and you want a certain result, you are going to work to get it. How do you do that? Fund a representative, send lobbyists to assure them you can help with writing legislation, offer them a good job when they leave. How many people leave Congress and go to become truck drivers and secretaries? Essentially nobody. They go on to work in a corporate law office, something like that. This is no conspiracy theory – this conspiracy is called capitalism.

But it seems not just corporations are trying to influence politics.

There’s a huge furor in the United States about alleged Russian interference. But how about the fact that, I repeat, campaign funding alone predicts with astonishing prediction the results of the votes of representatives? That’s not interference in elections?

It certainly is.

But why is no one talking or writing about it?

Is it as if we are all living in some sort of illusion, when we pretend that this is democracy, freedom, and so on, but everybody knows that this is just theatre, or is it more sophisticated than that?

I would not say it’s an illusion; there’s a lot of reality to it. With all the flaws of American society, it’s still a very free country. Nobody’s listening in to what we are doing, here in my office at the University of Arizona. Nobody’s going to put us in jail. For example, I can teach a course in radical politics, like we are talking about now, in one of the most reactionary states in the country, at a state university, and nobody will stop me. These are real things, tangible signs of freedom. Let’s take the 2016 election, when all the attention went to Trump.

Were you surprised?

I wouldn’t say that. Of course, Trump’s election was a little bit unusual. But on the other hand, not terribly so. It’s not so surprising that a billionaire who spent practically a billion dollars with huge corporate contributions and enormous media support won the election. But something else was extremely unusual and never gets discussed: the Bernie Sanders campaign. This is the first time in American political history that a basically unknown candidate appeared, even one using the scare word ‘socialist’, which couldn’t be used in the United States. He had no corporate support, no private wealth, and no media support – the media ridiculed him or ignored him – yet he probably would have won the Democratic nomination, if it had been honest.

And he might have defeated Trump. Some surveys showed such a scenario was realistic.

By now, Sanders is by far the most popular figure in the country. That’s astonishing and it shows that things can be done outside the institutional framework, that nevertheless the policy is there, the politicians are there.

Today I talked at breakfast with a working-class American family from Ohio, staying in the same hotel. They said things very similar to what you say: that American politics is a corrupt establishment game, that democracy is dependent on corporations and the wealthy, but that change is actually possible. Only for them, the person who symbolizes that change is Trump. Because he is from outside the system, he is honest, “not even a politician, really”.

Well, Trump is actually at the very heart of that system. He’s playing a very good game. He plays the image of someone fighting for the common man. Meanwhile, while the press is focusing on his personal antics, something else is happening. The most reactionary elements of the Republican Party, the ones that have always worked with dedication for the rich and powerful, are passing legislation and executive actions to further enrich and empower the wealthy and powerful beyond anyone’s imagination. So what that family can see is the surface, the con-game, diverting attention away from what Trump is actually up to.

And what is he actually up to?

Let’s take the tax bill. The tax bill may give a few dollars to your friends from Ohio, but it’s the biggest giveaway to the rich and powerful in the history of the country. The few dollars for your friends will dry up in a couple of years, while the latter will expand immensely. It’s also creating a huge deficit, which is explicitly designed – no conspiracy here, they actually say this – to ensure that they can cut back on programmes that are of benefit to the general population: Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security. The idea of the Trump administration is to work with passion for the very rich and very powerful corporate sector, to play a game of acting like a person from outside while actually protecting those who are not only inside but deep inside.

So he can talk about “draining the swamp”, but in fact he’s adding water to it?

It’s overflowing, with gifts to friends. The worst thing is the liberal press is cooperating with this, they pay attention to Stormy Daniels, rather than what is happening on the legislative level.

Are they blind? Or is this a part of the whole theatre you talk about?

It’s about the concept of journalism, which should be about paying attention to what the powerful are doing, and you report that accurately to the public. Especially what they don’t want you to talk about. The most astonishing thing happening now, which would be screaming headlines in any country with a free press, is that the Republican Party is the most dangerous organization in human history.

What do you mean?

Precisely that. They are dedicated to destroying the prospects for organized human life in the near future. Even Adolf Hitler didn’t aim for that. That’s what out to be discussed.

You mean issues related to climate change?

Climate change is by far the most important thing; these are imminent, existential threats. The last time the world temperature was anything like this was several hundred thousand years ago, and the sea level was 30 feet higher. That’s what we are aiming at, in the near future.

Trump knows this, Rex Tillerson [then US Secretary of State – ed. note] knows this. They all know it. Trump, for example, is pretending there’s no climate change, at the same time he’s building walls to protect his golf courses from rising sea levels. Rex Tillerson was the CEO of ExxonMobil for 30 years, they have known all along exactly what’s happening. They have all the best information and have been producing scientific papers internally, while at the same time they have been maximizing the use of the most dangerous fossil fuels and funding denialist organizations. What’s the right word to describe that? I can’t find one. What’s the liberal press saying about it? Nothing. It’s much more interesting to talk about Russians meddling in the election, or a porn star saying she had an affair with the president.

Do you think they really know what they are doing, or are they in some kind of denial state of mind? This kind of populistic backlash pact, this anti-liberal, conservative rhetoric, is something we also see in Europe.

The family you mentioned from Ohio is very typical. There’s a game being played: as a billionaire television actor, Trump is playing his part very well. The liberal press plays its part, too, by condemning him. This benefits him, because then his base, for instance from Ohio, can say: there go those liberals attacking our man again. Meanwhile the people he is working for are tearing apart, not only all the prospects for future human existence, but also the day-to-day aspects of policy that benefit that very family from Ohio. The US health care system is an international scandal. It costs about twice as much per capita as comparable countries, but with some of the worst outcomes. There’s a very simple reason for that. It’s privatized, highly inefficient. Huge bureaucracy with immense administrative costs. It takes an enormous amount of time even to wade through the options available. The public has been in favour of some sort of national health care guarantee for generations. Whoever your friends from Ohio are, they need healthcare. They think Trump is working for them, while in fact he is working hard to destroy their future and also the lives of their grandchildren. The critics are playing the same game. They are talking about Stormy Daniels and not climate change. Who cares if he had an affair with a porn star?

It seems like everyone does. Here in Tucson, I have heard everyone talking about only this, on the streets and in the shops and restaurants.

I know. Apparently the 60 Minutes episode in which she talked about Trump was one of the most viewed ever.

Yes, but let’s stick to this guy from Ohio. He has his internet, Facebook account…

He probably watches Fox News, and gets his news from Facebook.

We are living in an era when distinguishing between reality and non-reality is very difficult. It’s like we don’t have the ability or the right education to make distinctions anymore?

What’s happening now is somehow exaggerated, but it’s always been pretty much like this. The difference was there were organized groups that could bring people together to combat concentrated power.

You mean in earlier times?

Back in the 1930s, when I was a child. Most of my family were first-generation immigrants from Eastern Europe: working-class, mostly unemployed, very little education. But they were part of organized groups, labour unions, which provided not only opportunities but ways for people to get together to act, to respond to things that were happening. The effects were significant, it drove the government to adopt social democratic policies, pushing the United States in the direction of the mainstream of Western Europe. Contrary to today, it was quite a hopeful period.

You also often stress that then people had hope for a better tomorrow, contrary to today.

Objectively it was much poorer than today, but psychologically people felt very different. They felt they could work together to do something, today people are separated and atomized. The neoliberal programmes have succeeded in turning people in to what Karl Marx once called a “sack of potatoes”. He was criticizing the authoritarian rulers of Europe, who wanted people to be alone, isolated, frightened, angry, unable to work with others, without unions or functioning political parties. When you are alone in facing strong powers, all you can do is find something to grab onto: religious extremism, conspiracy theories, etc. If you can talk to your neighbours, it’s different. This neoliberal achievement is quite significant. When Margret Thatcher said there is no society, there are only other individuals, paraphrasing Karl Marx, she kind of knew what she was talking about.

Alan Greenspan, the former head of the Federal Reserve, once testified to Congress – during the period before the crash, when he was still exalted as a great figure – about the alleged great success of the economy he was managing, in which wages had actually stagnated for 30 years. He attributed the success to growing worker insecurity: the working people, he said, are so intimidated, so isolated, that they will not ask for greater benefits, that’s great for the economy, profits go up, no inflation, the Fed does not have to raise interest rates, just perfect. But the effect is what you are seeing. Anger, fear, irrationality, susceptibility to PR games like the ones Trump plays.

The second thing I’ve heard people talking about constantly here is the Cambridge Analytica scandal – in a way, this is a classic example of political PR.

Whatever Cambridge Analytica did is trivial as compared with public, open campaign funding. That’s what distorts the political system. Nobody’s talking about that. It’s as if you are looking at a mouse when there’s an elephant over there. The same with the alleged Russian meddling. Whatever it is, it can’t begin to compare with the control over the electoral process and the actions of representatives simply by private power.

Where is this all leading? To a new world order? Another world war?

Well, there are very dangerous things happening. The tensions on the Russian border could blow up at any time. Here and in Poland it’s described as Russian aggression. But notice that it’s on the Russian border, not on the Mexican border. There’s a reason for that. If we go back to 1991, Gorbachev had a vision of a common European home with no military blocs, with cooperative systems from Brussels to Vladivostok. The US had a different vision, to expand NATO up to the Russian border, in violation of promises to Gorbachev. If you move a hostile military alliance up to the Russian border, you are going to have problems. Some statesmen warned against this very strongly, and now we are seeing it, like Putin’s last speech about the nuclear programmes. It was played up here, but if you actually read that speech, what he was saying, though frightening enough, was that they are undertaking a response to the US departure from the ABM treaty. The US is building up what are called missile defences right on the Russian border. Everyone understands that missile defence is a first-strike weapon. Furthermore, these ABM installations are dual-use. You can put an anti-missile system in them, or a missile in them. These are bristling right along the Russian border. If anything like that were happening on the Canadian or Mexican border, we would go to war tomorrow to wipe them out. What Putin was saying was that they would take counter-measures. That is of course dangerous, but it’s not an aggressive move. This is also happening in the case of Iran, where the United States is moving systematically towards terminating the agreement with Iran. John Bolton, who was just appointed National Security Advisor, has been writing articles for years that we should just bomb Iran without waiting. Does that bode well for the future?

Not very well.

We are getting awfully close to nuclear war. Do you follow the Doomsday Clock, the symbolic gauge of the nuclear threat created by atomic scientists at the University of Chicago in 1947?

Yes, it shows two minutes to midnight; to global devastation.

Yes, that’s after a year of Trump. That’s as close as it has been since 1953, when the Soviets and Americans loaded hydrogen bombs.

Many analysts think that the tensions between the United States and North Korea are just a kind of boyish struggle, like a theatre.

If you look at the record of the nuclear age, it’s frightening. There are many cases when we came literally within minutes of total destruction.

Maybe the false-democracy situation you described earlier, with wealthy and powerful corporations ruling the world, somehow paradoxically prevents a global catastrophe?

How would they prevent it?

They simply want to survive and make money.

The problem is that they want to make more money in the short term. Let’s take Exxon-Mobil again, a very striking case. Back in the 1970s, Exxon-Mobil scientists were some of the first to discover the enormous ominous danger of global warming. They were publishing papers internally, as we now know. How did ExxonMobil react? By expanding the use of fossil fuels and funding denialist organizations, to try to cast doubt on what they knew was true: that we are moving towards terminal disaster. So yes, in the short term you make a little more money, but après moi, le déluge.

This is hard to understand in the psychological sense. How can someone be so blind to the long-term consequences of their actions.

I have no idea, but this kind of thing goes on all the time. I cite in my book an amazing example which I just can’t understand why historians never talk about. It’s what happened around 1950 when the US had essentially total security. But there was a potential threat in the distance, that someday there would be Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles with nuclear warheads that would threaten the United States. There was a possibility at that time to negotiate with the Russians to prevent the development of such systems, something the Russians might very well have accepted, as it was more of a threat to them than to the United States. But no one, not a single internal paper, even suggested the idea of protecting the United States from destruction. It just never occurred to anyone.

You have said many times that if we lived in a society designed according to the rules of classical liberalism, for instance, we would be fundamentally rational creatures, making rational decisions. This is the essence of your anarcho-syndicalist project, arguing that this is not some utopia, only a quite realistic prospect. But, of course, there are a lot of people who do not want us to be rational. The whole advertising and PR sphere is doing everything to make us behave irrationally.

In the case of the advertising industry, it’s conscious; it’s not a secret that their job is to delude you into buying things. But in the case of the general prevailing ideology, it’s not really a conscious decision, it’s just conformity to existing structures. Like what Hannah Arendt wrote about Eichmann being just a bureaucrat doing his job – take the easy way to live, don’t ask too many questions, don’t rock the boat. Think what you are supposed to think, try to protect yourself and get ahead. Under those conditions, we easily become a slave to ideological systems.

In Daniel Ellsberg’s latest book, which I highly recommend, he describes the atomic scientists designing the first tests for the atomic bomb. These were some of the most brilliant, educated people in the world. They knew that there was a possibility that an atomic explosion might ignite the Earth’s atmosphere. Not a high probability, but a possibility that testing the device might destroy everything. Did they try it? They did. You can’t get a higher grade of human intellect and morality than those people.

I think there’s a similar story with those who are openly facing the fact that we are racing towards terminal destruction, but say: fine, let’s go ahead and accelerate it. Let’s pull out of the Paris agreement and expand the use of the most destructive fossil fuels. Take a look at the business press, written by many sensible, honest people. There is article after article about oil production, price levels, about how the United States is now surpassing Saudi Arabia in fossil fuel production, but try to find a phrase about how all of this is accelerating the race to destruction – what ought to be the headline! Occasionally, there might be a mention on the back pages. All of this acceptance of what Antonio Gramsci called hegemonic common sense is just overwhelming.

Modern psychology has a concept of reducing epistemological dissonance, for example. Our mind can disassociate, with the right hand not knowing what the left hand is doing.

It’s easier to be safe. Safety means not challenging things. All through history people who have challenged orthodoxy have gotten in trouble. Such as the dissidents in Eastern Europe, or those in Central America, who were treated much worse. Even in Ancient Greece, Socrates had to drink hemlock for corrupting the youth of Athens by asking too many questions.

OK, then in light of all this, I want to ask you: What can we do? Or is it already too late?

I think we have a lot of opportunities. Take again the Sanders campaign. After all, he is the most popular political figure in the country, but he came out of nowhere, with no media support. But the popular movements that grew out of the campaign could be a very powerful force. Take the American labour movement, which is now almost crushed, but this is not the first time. In the 1920s what was a vibrant labour movement was crushed, but it revived in the 1930s to make major progress. That can happen again.

How do you feel after all of these years of activism and writing about politics, when you see what is going on in the world? Do you feel disillusioned, bitter mentally?

It’s not a matter of disillusionment. There have been a lot of achievements. We have a kind of legacy of past struggles, so we can move forward on a higher plane. On many issues, such as women’s rights, the struggle is largely won and we can go on to other things. What is new today, actually has been new since World War II but is exaggerated now, is that we are literally facing the imminent question of whether the human experiment will continue. Will we destroy everything with a nuclear war, or destroy everything through inaction on climate change? Those are questions that have to be answered in this generation.

What will happen, do you think?

I don’t think there’s an answer. The choice is in our hands.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Noam Chomsky:

An American linguist, philosopher, social activist and public commentator. He is called the father of modern linguistics, who contributed to the emergence of cognitive science, psycholinguistics, and information theory. He was born in 1928 into a family of Ashkenazy Jews, who had emigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe in the early 20th century. At the age of 16 he began to attend the University of Pennsylvania, studying philosophy, mathematics, and linguistics. In 1951 he was employed at Harvard University; since 1955 he has been associated with Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he is now a professor emeritus. Since August 2017 he has regularly lectured at the University of Arizona.

His theory of universal grammar, which holds that the ability to learn a language is due to an innate faculty, is one of the mainstays of the modern study of language. Aside from his purely scientific work, Chomsky has been continually engaged in political commentary. Considered by many to have extreme leftist and pacifist views, he describes himself as an anarcho-syndicalist or free socialist. He is famous for his very sharp criticism of the United States. Opposing what he sees as imperialist US policy, he was engaged in protests against the Vietnam War, and he also staunchly condemned the “war on terror” declared by George W. Bush following the World Trade Center attacks of 2001. He is also highly critical of the policies of the state of Israel.

His major books include Syntactic Structures (1957), Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), Lectures on Government and Binding (1981), and The Minimalist Program (1995) on linguistics, and American Power and the New Mandarins (1969), Manufacturing Consent (1988), Understanding Power (2002), Who Rules the World? (2016), and Requiem for the American Dream (2017) on politics. He has been living in Tuscon, Arizona for several years now. He is one of the most cited scholars in the world.

Introduction and biography translated from the Polish by Daniel J. Sax