Whenever we feel tired of life and afraid of the world around us, we look for a retreat. Dreams of distant, magical places, of wonderful moments in which you can forget ‘everything’ and ‘find yourself’ lead to dangerous areas of the mind.

In psychology, a special state of mind is known where the patient shuts themselves in a mental bubble; here, although they are suffering, they feel safer than in the world outside. “I have come to refer to [these states],” writes John Steiner in his book on this subject, “as psychic retreats, refuges, shelters, sanctuaries or havens.” A retreat arises as a reaction to fear. “It is possible to observe patients in a ‘delusional mood’, in which extreme anxiety is accompanied by depersonalization and feelings of ill-defined dread, who may actually appear relieved as the defuse dread gives way to fixed systematized delusion.” As if only in imaginary worlds is it possible to find security and liberation from fear and pain. “The retreat then serves as an area of the mind where reality does not have to be faced, where phantasy and omnipotence can exist unchecked and where anything is permitted.” This is the feature that often makes the retreat so appealing to the patient and usually involves the use of perverse and psychotic mechanisms. Retreat is not just an issue for patients in psychiatric hospitals or those undergoing psychotherapy. Whenever we feel tired of life and afraid of the world around us, we look for a retreat. Dreams of distant, magical places, of wonderful moments in which you can forget ‘everything’ and ‘find yourself’ lead dangerously close to the borders of a retreat. The border that separates delusion from reality is deceptively subtle.

Time outside of time

It’s a beautiful day in August. The summer holidays. After an overnight stay at Lake Balaton, we’re driving south along the motorway. We pass signs written in a language we don’t understand. There is something poignant in the lack of similarities between Hungarian and any other language in the world. To go to Hungary is to immerse yourself in complete linguistic otherness – no associations, no continuity with what you know.

But the fact that we were lost in translation didn’t matter much. Had someone asked where we were, we could simply have said that we were on the motorway. In a sense, an extraterritorial space. Fenced off from its surroundings, it allows you to travel at a comfortable remove from the troublesome local context. When you are driving on the motorway, it is hard to pinpoint where you are. You’re somewhere between the beginning and the end of your journey. The signposts you’re speeding past inform you of the distance that separates you from your destination. But that information keeps changing. If someone phones and asks where you are, you reply ‘near X’, or ‘I’ve passed Y’. At any given moment you’re somewhere different.

There is something very appealing about this particular situation. For a few hours, it’s good to be free from the restrictions of time and place within which we reside every day. A journey is a kind of pause in everyday life, time outside of time, a transcendent moment. Travelling on the motorway, paradoxically, you are in motion and as if motionless. In a time outside of regular time. Outside of the life that’s going on beyond the motorway barriers, and outside of the life you lead every day. For a few hours, you’re not concerned with the routine of ordinary errands, worries and tasks. The sooner I pass the signposts, the more I feel that what is beyond the motorway does not concern me. In my car, it’s as if I’m in a capsule, in which I’m protected from the burdensome world. I know it’s an illusion, but it feels nice to surrender to it.

Another place even more illusory than the motorway is the airport. You enter, drop off your luggage, then go through security as if through a cleansing sluice. Once you get through, you feel – as Alain de Botton writes in his book A Week at the Airport – as if you’re leaving church after confession or synagogue on the Day of Atonement. Cleansed, relieved of all suspicions, you can carelessly stroll around the shops, go for something to eat or drink, read, or just stare at other people. You have no important problems to solve. You’re moving around a space where nothing matters too much. De Botton meets a clergyman who works at the airport. He asks: “What do people tend to come to you to ask?” “They come to me when they are lost,” replies the Reverend. “Yes, but what might they be feeling lost about?” “Oh,” sighs the Reverend, “they are almost always looking for the toilets.”

Cast aside the ‘old you’

The feeling of detachment and liberation from the burdens of everyday life grows when you look at the information board in the departure hall and you can envision yourself standing in front of a wide open gate to the world, each of the displayed destinations representing an alternative to your current life. You imagine reaching one of these destinations, and it turns out you’re someone completely different, like a man de Botton meets who confesses that he has just visited his wife and children in London, but in Los Angeles, where he’s flying to now, he has a second family who know nothing about the first. He has a total of five children, two mothers-in-law, and he doesn’t seem particularly troubled by this state of affairs. It’s nice to think that you can change your skin – not only change your environment, but become someone else yourself, cast aside the ‘old you’. A shoe cleaner working at Heathrow tells de Botton that people rarely have their shoes cleaned at random. They do it when they want to cut themselves off from the past, when they expect a change on the outside to initiate one on the inside.

Isn’t the airport a retreat? The time we spend there is more unreal than it seems. Although it’s hard to admit, the new places, sights, flavours and smells towards which we are heading are not of great importance in themselves. Essentially, according to de Botton, we remember little from our travels. New sensations drown in a mass of previous impressions. When we set off on another journey, rather than these things, the most important part is immersing ourselves once again in the atmosphere of packing, leaving and waiting.

French anthropologist Marc Augé describes particular spaces such as motorways, airports and large shopping centres as non-places. In non-places, there are plenty of different things, sights and possibilities. Everyone can see everything, but that everything doesn’t form any kind of whole. According to Augé, there are no common points of reference. “They play no part in any synthesis, they are not integrated with anything; they simply bear witness […] to the coexistence of distinct individualities, perceived as equivalent and unconnected” [trans. John Howe]. In non-places you pass different people, but you’re not bound to anyone, you see different things, but you don’t stop at any of them, everything is interesting, but nothing is important. And yet, a non-place, despite being stripped of meaning and free from deeper relationships, or perhaps because of this, entices and lures. A non-place is a promise that, as if in non-time, in a present stretching for hours or even days, you will be able to experience a unique lightness of life free from the banal everyday spectacle and the boring role that you play in it. A promise that you can experience yourself as someone else, free from onerous relationships and the unpleasant truth about yourself. A promise that you can take shelter as though in a sterile bubble, in a retreat in which, as Augé describes it, “neither identity, nor relations, nor history really make any sense; spaces in which solitude is experienced as an overburdening or emptying of individuality.” In an imaginary world, full of loneliness, devoid of meaning. And yet enticing, like a shopping centre on a day off work.

The shadow of one’s own place

Or how about sheltering in one’s ‘own place on Earth’ rather than in the nameless crowd of non-places? Full of memories, feelings, histories, written and unwritten traditions, stories about parents, grandparents, great-grandparents that can be passed on to children. A place that is an important point of reference, to which you eagerly return as a safe haven. For example, on public holidays such as Christmas Eve, when we try to get together with our nearest and dearest. It doesn’t matter how many people are around us. The important thing is that we are together, that gestures and words have meaning. The Christmas tree, real or artificial, is like the centre of the world. Similarly, the table, the wafer (if we maintain this tradition), and the dishes we serve. This seems to meet our yearning for a space in which we don’t have to struggle with anything or pretend anything, in which we’re accepted as we are.

Can you imagine a more beautiful illusion than the stories of Christmas, the holy places, the memories of homelands? Perhaps, in fact, they are an illusion. The famous researcher of religion Mircea Eliade writes about sacred time, which, separated from profane time, creates an enclave between the present moment and the future. Sacred time is a divine pause, a break in everyday life. In sacred time, material reality undergoes a transformation and extraordinary things happen. On Saint John’s Eve, the magical fern flower blooms; on Christmas Eve, animals speak with human voices. In sacred places, the body and soul are miraculously changed. Incurable diseases are healed, sinners return to the path of virtue. In the abandoned homelands, everything was beautiful, people were good, and the bread smelled like nowhere else on Earth.

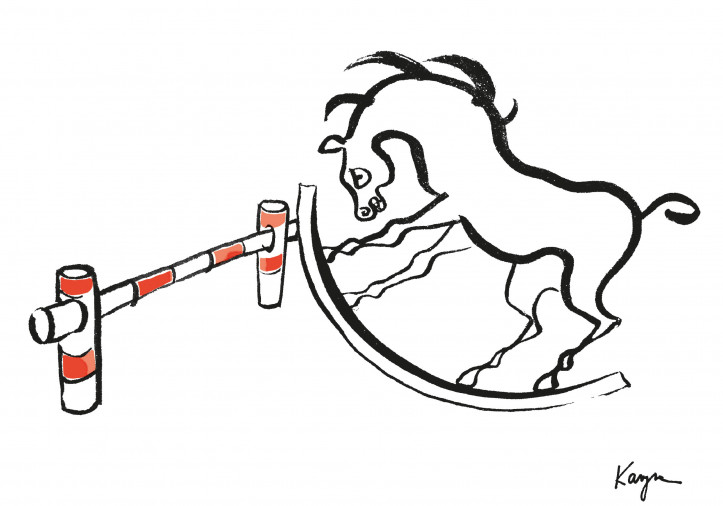

However, an evil shadow hovers over the illusion. The place has a negative, a dark side. It is not immediately apparent, but one’s ‘own place on Earth’ is burdened with original sin. Designating your own territory always requires the delineation of a border. These used to be the frontiers of a world inhabited by a human community. Behind them began emptiness, desert, wilderness, inhabited by wild animals and demons. And also others, strangers, barbarians. Looking different, speaking differently, eating different things. Their very presence threatens everything that is known, understood, safe. Sometimes they’d burst through the borders of our world. Not only as invaders – it sufficed for a train of Gypsy wagons to stop near a village, or a circus tent to be pitched on the outskirts of a town. Today they come as refugees. By defining the borders of your place, you designate a space for the other, for someone who is not one of us, whom we do not invite to our home, city, country, to our world.

The greater the fear of others, the more secure the borders. In his monograph Fear in the West, Jean Delumeau describes the barriers defending access to 16th-century Augsburg: “First, a hidden iron door, which the first guard opens […], pulls with a chain […]. After crossing this obstacle, the gate closes abruptly. The traveller passes under a roofed bridge over the city moat and reaches a small square, where he gives his identity and the address where he will be staying in Augsburg. The guard then rings a bell to notify his companion, who cranks a spring located in the gallery adjacent to his chamber. The spring first opens a gate – also iron, of course – and then, by means of a large wheel, raises the drawbridge […]. Behind the drawbridge a huge door opens […]. The foreigner enters through the door into a room where he is enclosed, alone and without light. But another door, similar to the previous one, allows him to reach a second room, where there is light and he can make out a bronze vessel hanging from a chain. He places a toll inside. The guard […] pulls the chain, takes the vessel and checks the amount the guest put inside […]. If he is satisfied, he opens another big door, similar to the others, which closes as soon as the guest passes and is finally in the city.”

Security may be symbolic, but still just as powerful as the walls and gates defending Augsburg. It may be a detail of clothing, ritual robes donned for special occasions, written or unwritten marriage rules, bans and orders relating to food, and so on. It is safe and pleasant to find yourself in a space marked by gestures, words and signs known only to yourself, inaccessible to other people. To imagine an invisible border separating you from others. It can easily happen, however, that fear of others makes maintaining this border the highest imperative. Sometimes with surprise, and sometimes with disgust, we read about the customs of various traditional environments: from the seemingly amiable eccentricities of the Amish to the criminal practices of conservative Muslim communities, such as honour killings, whipping, stoning and female circumcision. Not only Muslim, but also Christian, Buddhist – every community has its own madness. When anxiety permeates a community, what becomes most important in its tradition is not what unites, but what excludes. Dissenters are shown no mercy. Tradition turns into a collective psychosis, and place into a hellish abyss.

Stop chasing the extraordinary

From the outside, it is easy to wonder why some people are so keen to choose life in these terrible, closed worlds. It is easier to understand when you think about the desire to find a psychic retreat. We can only imagine what terrifying fantasies about the outside world were spun by the people of Augsburg. A century after the times described by Delumeau, Europeans were still imagining that people on other continents had the heads of dogs, or no heads at all, or no mouths, or that they were centaurs… And what was thought and said, then and later, about Jews posing a threat to Christians? Nothing has changed. What do Orthodox Muslims, or Orthodox Jews, think about ‘infidels’? What are politicians in Poland saying today about the ‘germs spread by African refugees’? It is better to fence off the borders, slam all the doors, not allow anyone in, and not allow anyone to break out of the collective psychosis. And the fact that it’s hard to live in a psychotic world? Tough, security comes at a price.

Is there an escape from the retreat trap? How can you fulfil your dream of a moment’s peace, a divine pause, when a drop of eternity flows into a busy mortal life, when you can delight in the fullness of life, be in harmony with yourself and the world? How can you find this and not yield to the delusion? Or perhaps there’s no need to run from anything or to isolate yourself? In his renowned book There Is No God and He Is Always with You, the modern Zen master Brad Warner writes: “If there is any aim to zazen practice, the aim is to teach you how to be quiet enough to stop chasing after extraordinary states and simply notice who and what you are right now.”

We’ve returned home from our holiday trip. I’m walking along a forest path. It’s one of the last days of summer, warm early evening. I feel the forest closing in around me. I have the impression that with every step, I am being consumed by a great, living being. I’m moving quite quickly, but I’m not in a hurry, I’m not running away from anything, nor aiming for any particular destination. I can hear the sound of a stream, the call of a bird. I simply am.