Axel Munthe liked lilies of the valley best. His favourite colour? Italian blue. Favourite foods? Apple pie, blueberry jam, and wine, which he considered the beverage of the gods.

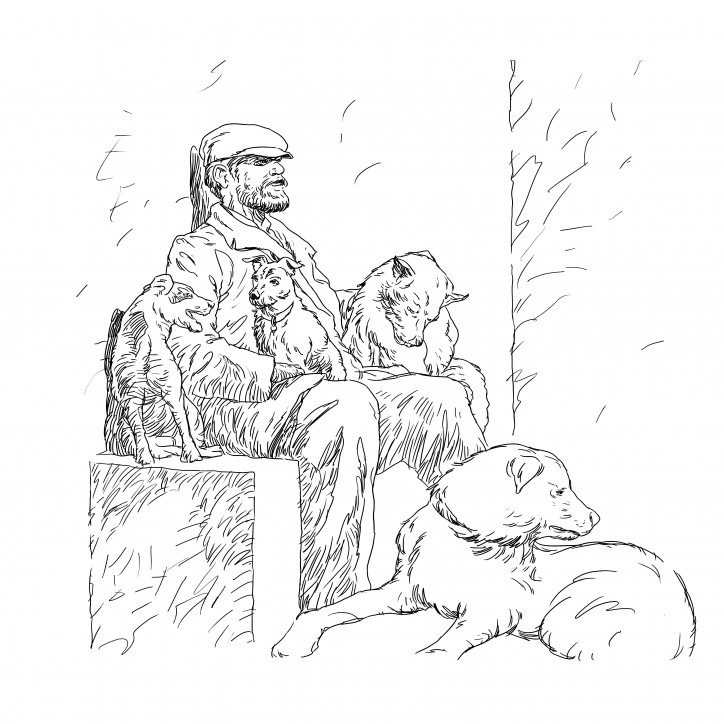

The picture shows a man of middle age. He’s wearing a coat, warm trousers and a cap, so it must be the early Italian spring, but it could also be autumn. The man sits on a bench, leaning back on a wall. His eyes are closed, and his face turned to the sun. The natural light brightens his cheeks and throws the dark shadow of his head on the flat white surface behind him. Another light seems to emanate from the interior of the photograph, and also engulf the dogs surrounding the man. There are five of them, some larger, some smaller. Two have nestled under his arms, the third sticks to his shoulders, the fourth lies at his feet, and the fifth looks placidly into the camera from a patch of sunlight next to the bench. The entire human-canine group pulses with the luminous harmony associated with sainthood. It’s governed by a post-humanistic equality. At the very least, the man is not the central figure; if anything it’s the huge, calm dog in the circle of light, which is where I should have begun. Close to him – next to him – other dogs warm themselves, and among them is the man in the cap. A dog of sorts. Because if we anthropomorphize animals, why not ‘caninize’ humans? Allow me to introduce Axel Munthe. Somebody took this photo of him on Capri at the end of the 19th century.

The orgies of yesteryear

This island in the Bay of Naples is associated primarily with the orgies of Tiberius Caesar, who in 26 CE moved here from Rome and ruled the Empire remotely, until in the end, absorbed in debauchery, he completely lost his heart for power. On Capri he had 12 villas, a harem of sexual slaves (male and female), as well as an impressive collection of pornographic books, sculptures and paintings, which he constantly expanded. The emperor wallowed in licentiousness as both a spectator and a participant; he ruthlessly raped women and men, as well as abusing minors (according to some accounts even infants), and more than one person took their life because of him. The faint aftertaste of that atmosphere can be found in the Henryk Siemiradzki tapestry Orgy on Capri, where in addition to a procession of revellers, we can see two naked corpses.

The ruins of Tiberius’ main villa, the Villa Jovis, can still be seen today, though I swear there’s nothing to see there, and the debauchery itself seems over-advertised. 2000 years after the Caesar, overindulgence is coming out of our ears, along with the feeling that everything has already happened – as people we’ve been everywhere, tried everything, knocked over every taboo. We’re drowning in a flood of goods and stimuli, which we gulp down and suddenly regurgitate in the form of psychological disturbances, only to suck in even more a moment later. The yearning for freedom has changed into a compulsion to rack up new impressions; transgression combined with exhibitionism, in plush handcuffs lined with boredom. It’s clearly visible that this is not where the path lies. That’s why I seek the path somewhere else. Not in the Villa Jovis, but in the Villa San Michele, with Axel Munthe.

The demonic doctor and the birds

Munthe was born in 1857 in Sweden. In Uppsala, Montpelier and Paris he studied medicine, philosophy and gynaecology, in which he earned a doctorate. He also studied under the haunted Jean-Martin Charcot, who during the time of public shows provoked attacks of ‘hysteria’ in women, and with whom Munthe eventually cut ties.

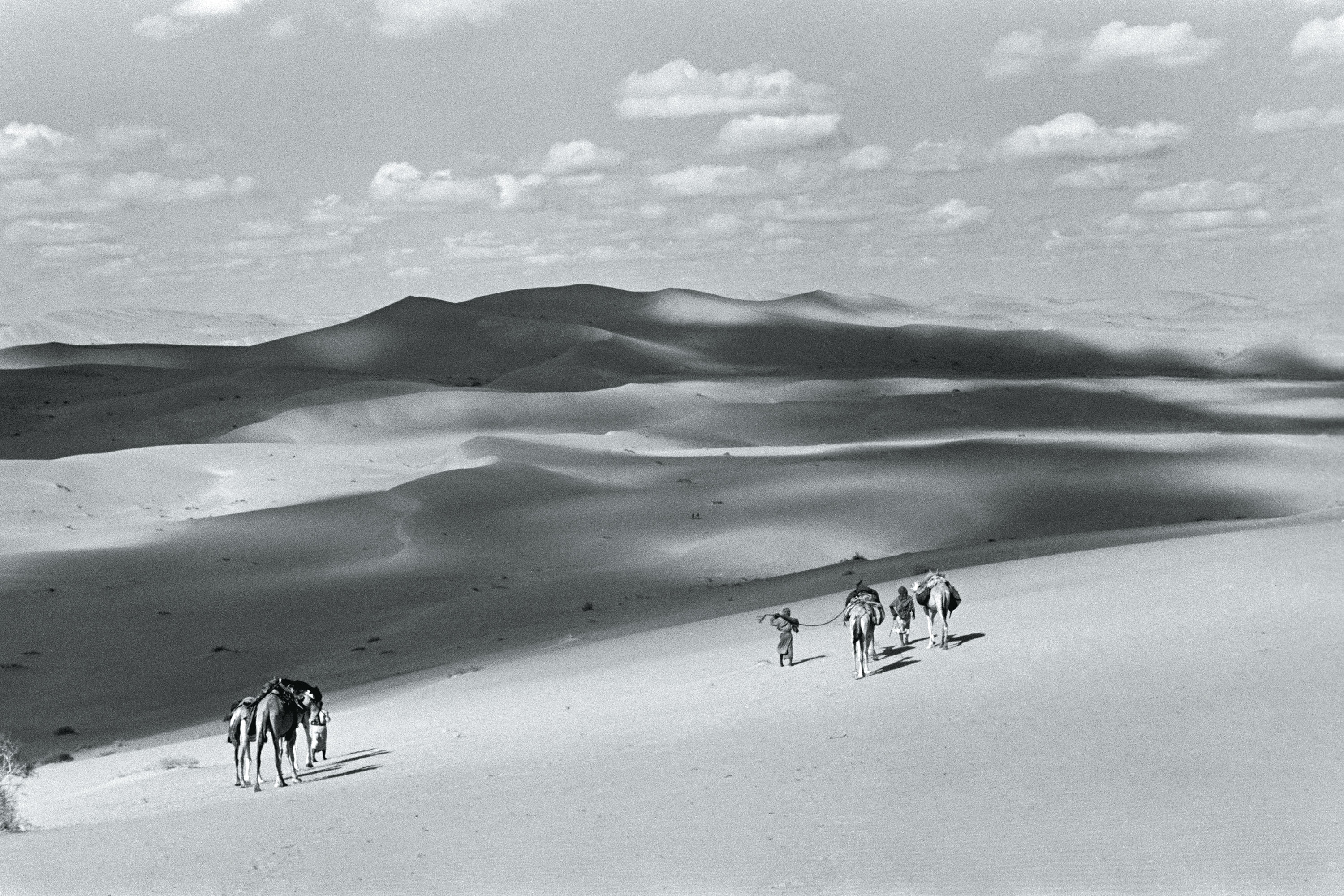

He arrived in Capri during a trip through Italy in 1875. That’s when he discovered the mountain village of Anacapri, and in it the ruins of the chapel of San Michele. He wanted to settle there, and he never gave up this dream. After a few years of sacrificial practice during typhus and cholera epidemics in southern Italy, he moved to the island, bought the house along with the ruined chapel, and started to bring his idea to life. He designed the Villa San Michele, and also did much of the building work himself over the following years.

In 1892, his acquaintanceship with the Swedish royal family began – in particular with the wife of King Gustaf V, Queen Victoria of Baden. As the court doctor, Munthe convinced the unhappy monarch to make annual visits to Capri. One year, the queen was accompanied on her trip by her daughter-in-law, the Russian princess Maria Pavlovna, who judged the doctor’s influence on her mother-in-law to be demonic, and years later accused him of sexual assault. The locals believed Munthe had an affair with Victoria, but even so in 1942 he settled in the Swedish court as an official guest of Gustaf V, where he lived out the war and breathed his last shortly after turning 90. His ashes were scattered in the North Sea.

Axel Munthe was married twice and had children, but in his bedroom in the Villa San Michele stand statues of naked men with their members at eye level. He himself searched out the ancient artefacts decorating the villa and garden, guided as much by the taste of a collector as by unclear criteria of a personal nature, meaning that specialists don’t value his collections. During World War I, he worked as a volunteer with the British Red Cross. At work, he was inclined toward alternative medicine, and favoured a right to euthanasia. He believed in God, but doubted immortality. In his chapel, he played music and meditated. He liked to sing Schubert songs, and believed that the West had lost its moral compass. He wrote a lot, but is best known for The Story of San Michele, an autobiography published for the first time in 1929, and translated into more than 50 languages.

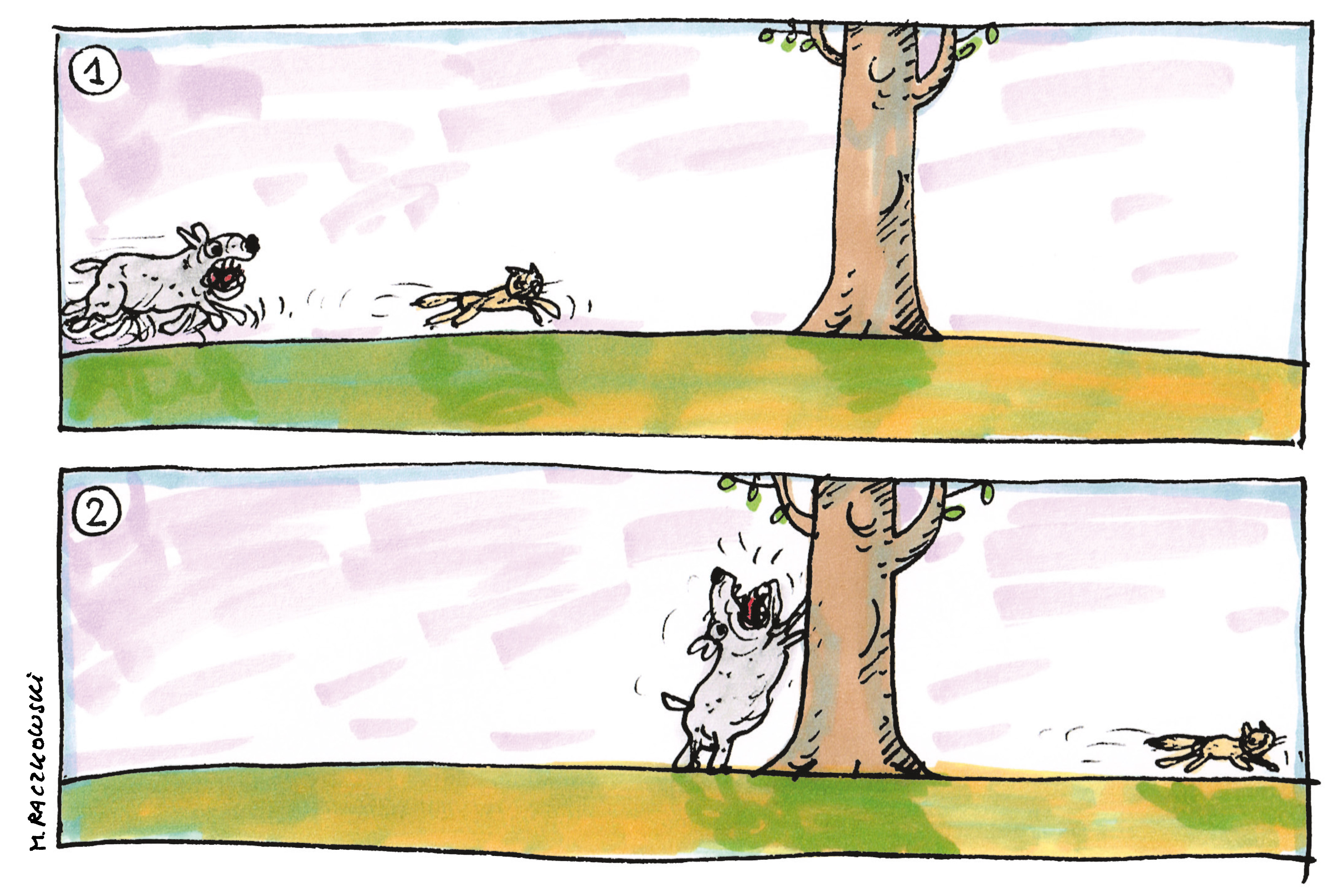

In the Story, Munthe devotes a great deal of attention to animals, always defending them over people. “To become a good dog-doctor it is necessary to love dogs, but it is also necessary to understand them the same as with us, with the difference that it is easier to understand a dog than a man and easier to love him,” he writes. “The intelligence of dogs is proverbial, but there is a great difference of degree, already apparent in the puppies as soon as they open their eyes. There are even stupid dogs, though the percentage is much smaller than in man.. […] They are all representatives of the most lovable and, morally speaking, most perfect creation of God.”

He did the most for migrating birds – doves, thrushes, turtles, curlews, quail, orioles, skylarks, nightingales, swallows and robins, which each spring arrive in their thousands on Capri. These avian migrants, exhausted from their travels, faced a cruel, agonizing death on the island. On the cliffs of the Monte Barbarossa, just above the Villa San Michele, the locals would catch them in nets and either send their small bodies to restaurants in Paris, or blind them, turning them into a mad lure for the next victims. Shaken by the executions that were taking place under his nose, Munthe intervened with the authorities, and when that didn’t help, he trained his dogs to bark at night, and scared the birds away himself with cannonades. After years of this noble partisan warfare, he managed to buy Monte Barbarossa from a certain butcher (with help from Queen Victoria) and change the avian Golgotha into a nature preserve. Although Munthe certainly wasn’t perfect, there’s no way that he can be accused of impractical sentimentality. He gave the profits from the reserve to the poor residents of the island, knowing that hunting the birds had been their main source of income. It was thanks to him that today the Capri Bird Observatory operates on Monte Barbarossa, under the care of Swedes, like all of the Villa San Michele.

Sleep, the brother of death

Munthe’s property – his house and garden, on a steep cliff – is a work of art and a picture of his spirit. It expresses both unease and a desire for harmony. From here, there stretches out a breathtaking view of the Sorrentine Peninsula and Vesuvius, but most of all, the blue expanse of sky and sea – the manor is suspended between these two elements. Strangely, the Villa San Michele, maintained in the spirit of romantic symbolism, never for a moment seems empty, even though nobody lives there. Perhaps that’s because of the rustling wind that seems to betray, as in the book of Genesis, the hidden presence of the creator, or maybe because of the works of ancient art, which live a life of their own. In this small space, there are more than 1000 such works, but, of course, the ones that make the strongest impression are the sculptures, placed deliberately around the house and garden, among the trees, shrubs and flowers.

Munthe liked lilies of the valley best of all. His favourite colour was Italian blue. His favourite foods were apple pie, blueberry jam, and wine, which he considered the beverage of the gods. He dreamt of a painless death, and in his garden, right by the entrance, he placed an impressive bas-relief with the head of Hypnos, the god of sleep and oblivion. A little farther on, in the place where the ground under your feet runs out and the cliff is at its steepest, you come across the powerful hindquarters of a stone sphinx, turned to face the sea. The face of the creature can’t be seen, and this inability wears on you, but the owner set it up so that the only way to see the sphinx’s eyes is to jump off the cliff. Then you’d see them for a split second; the riddle of the sphinx, the mystery of death. In 1885, Munthe noted the thought, taken from Gregorovius, that Capri recalled “a sleeping sphinx, or an ancient sarcophagus.” Perhaps this thought allows him to be better understood. He lived on Capri as in a sarcophagus, to await in it the end of his days, and before his eyes he set a sphinx – the riddle and the temptation of death. Is this what he was thinking about that day on the bench, sunning himself with other dogs?

Translated by Nathaniel Espino