On a concrete house full of free love – for nature, the avant-garde, for creative expression – built in gloomy times, and demolished in contemporary ones.

During my architecture studies, Jan Szpakowicz was for me a star on the order of Kurt Cobain, and the unassuming house that he designed in the 1960s in Zalesie Dolne near Warsaw, where he lived with his family until he left for France in 1992, was a real discovery. Even though it was an exceptionally avant-garde building for that time (and even for much later times), it couldn’t be found in guides or albums. It didn’t exist at all in the collective memory until the moment several years later, perhaps a dozen years later, when the architect Łukasz Wojciechowski found it in old issue of an industry publication. Fascinated by this discovery and with great dedication, he decided to promote it, which made the house an immediate sensation on the pages of not just domestic but also foreign portals about design, to a large degree changing the lens through which we perceive the heritage of late Modernism in Poland. This was nothing strange – it’s a building that despite the passage of 50 years since its construction still seems exceptionally modern.

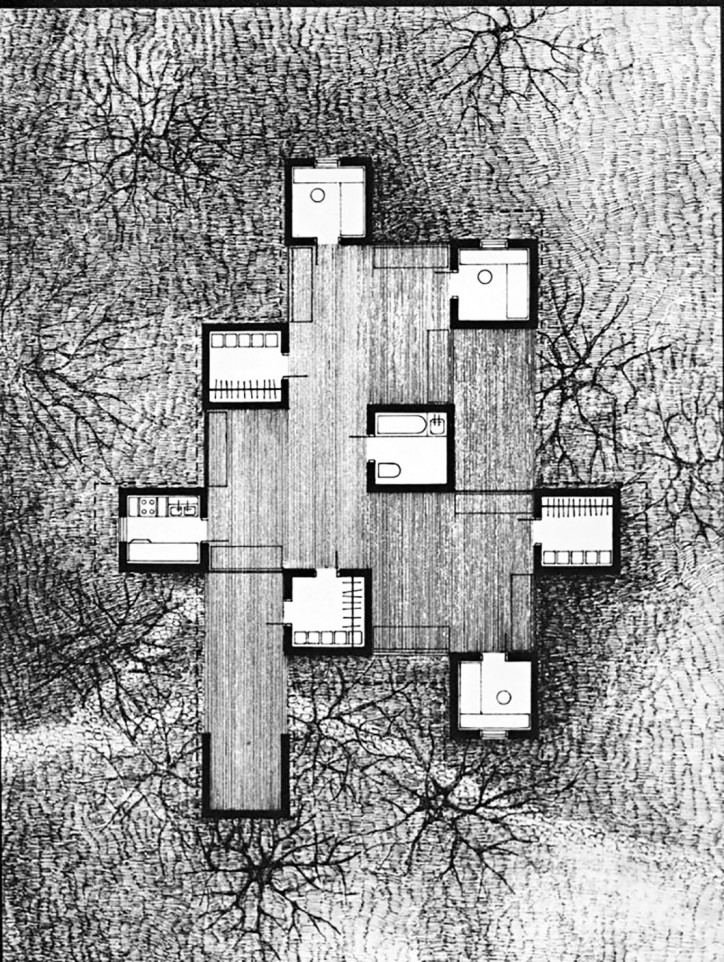

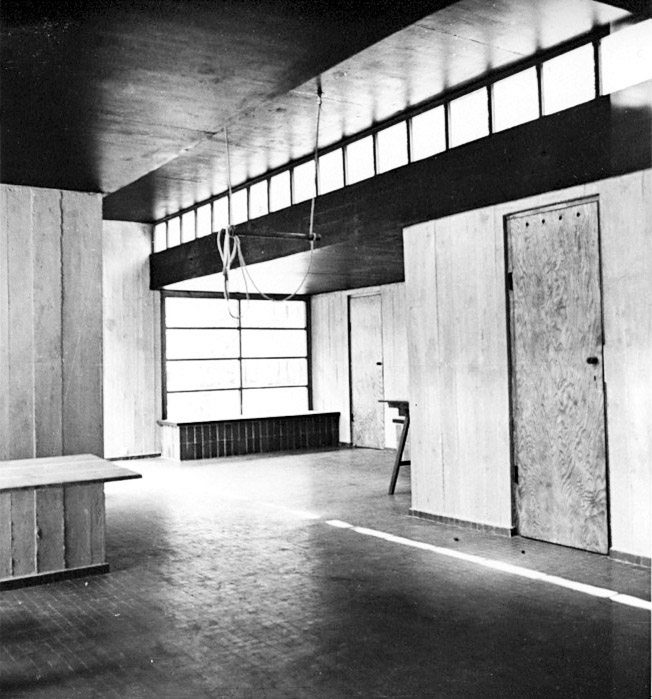

Such an atypical house could probably be built only for oneself. In its plans and cross-sections we can see great if not obsessive consistency, and mathematical precision. In nine regularly distributed concrete cubes, of length and width of exactly 2.4 metres, is found everything a house needs in order to function: a kitchen, bathroom, closets and bedrooms. Between them there spills out a roofed space, open to the outside world, whose borders are delineated by great wooden windows, letting lots of daylight into the house. When looking at archival photos, it’s easy to note the architect’s basic plan: the building is only a background for nature and for the life of its residents. Closed in their square forms, the rooms here also function as pillars holding up the dark lines of the roof, which seem to float freely at various heights. The house has quite a raw, ascetic character, and simultaneously gives an impression of cosiness and warmth thanks to the ever-present and carefully framed greenery, complementing the composition made up of concrete, wood and ceramics.

“Everybody accused us of formalism, but in reality it was a very comfortable house,” Mr Szpakowicz says about the building, with passion and unconcealed sentiment. “It was a great place to live.” Even today, he remembers perfectly every detail of the design, and can easily describe all the dimensions and technical solutions. He thinks the size of the bedroom was perfectly sufficient. I’m meeting with him and his wife, Grażyna Szpakowicz (who worked as a historic buildings conservator), in the centre of Warsaw. I’m quite lucky, because they’re in town only briefly. I hear their stories about how the design process looked in Poland a few decades ago, and outside the window the remains of the Eastern Wall are dying – one of the most interesting concepts in post-war modernist urban planning, killed off by the unsuccessful revitalisation of the Wiecha passage, the reconstruction of the Rotunda and the skyscraper next to it, whose shape must have been generated by a lottery machine. We have a problem with understanding and respecting the difficult architectural heritage left to us by the older generation of designers.

“It was a difficult period, but seeing what certain contemporary developers are doing with the city, you really can appreciate it,” Ms Szpakowicz says to me.

The story of the Szpakowiczes’ house in Zalesie doesn’t have a happy ending, either. When I ask about the state of the building today, I still hope to the end that the rumour which made its way to me earlier won’t be confirmed. Unfortunately, nothing remains of it. The kiss of death for this concrete residential structure turned out to be its popularity. The new owner decided to get rid of the house at a time when numerous groups of enthusiastic young architects, who wanted to see it live and photograph it, started appearing in the area, and that always means trouble. Nobody reacted in time, and today we can only hope that someday Filip Springer will describe this pearl of modernism from Zalesie in a new edition of Źle urodzone [Ill-born], and some eccentric millionaire will decide to rebuild it in an architectural amusement park for the sentimental, where, wandering between Supersam and the Chemia pavilion, they’ll be cured of all signs of longing and pangs of conscience.

Translated from the Polish by Nathaniel Espino