“The sky thickens and purples, but only a few drops fall onto the sand. It’s not the long-awaited shower, but the Tasmanian curse: a dry thunderstorm. The air absorbs the moisture before it manages to reach the ground. Embers that could have been easily put out by rainfall now spread into fires.” Emilia Dłużewska describes her travels in the paradise turned hell.

Why is it so hard to solve a murder in Tasmania? Because there are no dental records, and DNA matches everyone. It’s one of many jokes Australians tell about the island. Tasmania, located 240 kilometres south from the continent, is stereotypically branded as the poor, backwards province, where half-savage natives are forced to resort to inbreeding.

This doesn’t scare the tourists away, and they grow in numbers year by year. Most of them come here in the summer when the unforgiving climate is the most friendly – the average daytime temperature being just over 20°C. Unique wild landscapes are among the island’s most precious treasures. Tasmania is roughly the size of Ireland, but its population is not much larger than that of Palermo. Over half of the island is covered by national parks, reserves and protected forests, and one-fifth of the whole area is on the UNESCO World Natural Heritage list. The rest of Tasmania is mainly green, too: there are pastures, orchards and farming fields everywhere. Cape Grim, the northwestern point of the island, is known for having the cleanest air on Earth. Unsurprisingly, the local government, food producers, and travel and real estate agents are all obsessed with the word ‘natural’, promising Tasmania to be the place where you can finally breathe.

***

In mid-January, the famous Tasmanian air smells just like Polish allotment gardens in November. When we drive along the southern coast, the unmistakable stench of burned leaves and grass seeps into the car, despite all windows being closed and the air conditioning working full-on. The pinch of nostalgia goes away quickly. Tasmania has been on fire for almost a month now. The online map, managed by the state fire brigade, shows new spots lighting up nearly every day.

Fires in Australian forests are nothing unusual. They happen so often that the local plant species have gotten used to it – such as the evergreen banksia that hides its seeds in a thick shell, opening only with the help of the flames. This way, the seeds spread in the fertilized ground, cleared from any competition. Without fires, there would be none of the giant eucalyptus trees that grow in the Mount Field National Park in Tasmania – when the area is thinned-out after a bushfire, the trees drop their seeds to make the most out of this new space. The almost 100-metre-tall trees in Mount Field are second only to the Californian sequoias. The oldest remember the times from before the arrival of the first white colonizers.

Humans adapt, too. Tasmanian bushfires are seasonal; they happen in cycles. For families living outside the cities, the likelihood of having to escape the flames is so high that the Fire Department encourages all citizens to draft individual evacuation plans, including making lists of things to take with them and people to contact before leaving. Reaction time is crucial because bushfires are treacherous. Flames licking dry ground can spread instantaneously. The sparks and floating embers that precede them are equally dangerous. Sometimes a house catches fire even before the people who live in it can notice the blaze coming.

***

This year, it’s different. The fires started in December, and by January had reached a scale beyond the control of the local services. In the first week of January alone, the flames consumed 180 square kilometres of cool, UNESCO-protected rainforest. These areas, covered with thick moss and wrapped in delicate mist, are less colourful than their tropical cousins, but no less beautiful. The reason they landed on the UNESCO list, however, was not because of their beauty, but because of the plants and animals living there and nowhere else outside Tasmania. The fires are a threat to the rare species that have survived on the island since the times of the prehistoric supercontinent Gondwana, such as the Lagarostrobos franklinii (also known as the Huon pine) that grows along the Huon River. These small, thick trees, with thin twigs covered in scale-like leaves, look a bit like Thuja trees, and are some of the most longevous organisms on the planet – some can survive for over 3000 years.

Tasmanian firefighters (there are 250 professionals and almost 5000 volunteers in total) are supported by their colleagues from Australia and New Zealand. They use heavy machinery to carve out safety belts and set up miles of sprinklers to minimize the risk of sparking the fire. Planes drop water and chemicals to prevent the forests from burning. Local services block the roads and close down national parks; hundreds of people have been evacuated from the danger zones. Still, firefighters admit that until the weather changes, the best they can do is try to stop the fires from spreading. Weeks-long drought, combined with intense fires and high temperatures, make the bushfires impossible to defeat. They can only wait for the rain.

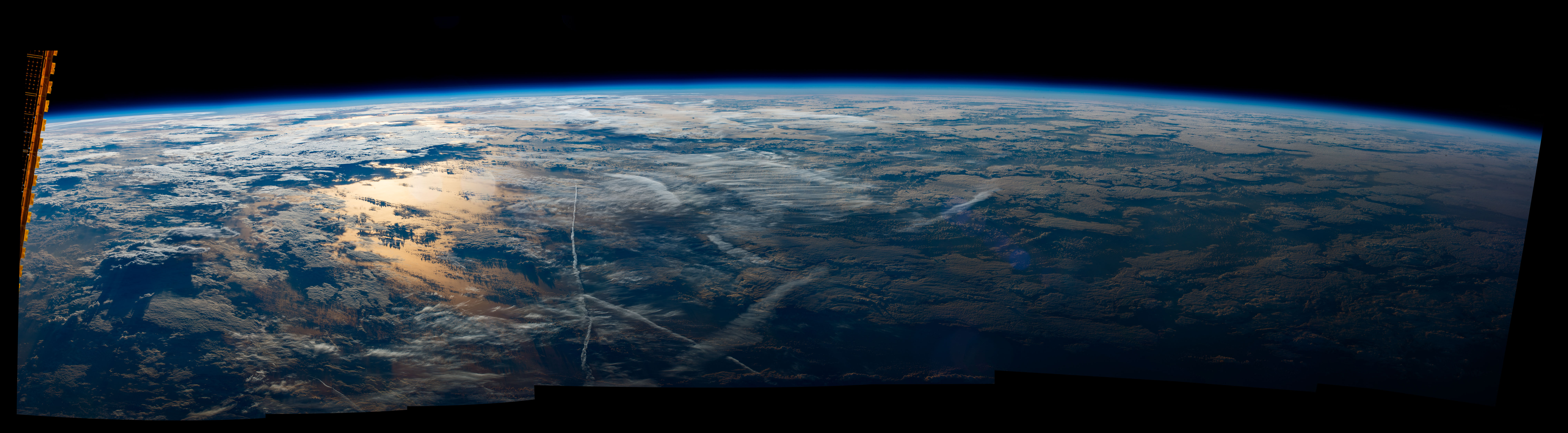

This year, summer temperatures reached record highs. Even though it was much lower than on the continent, thermometers still showed way over 30°C. And 30° here is very different from the same temperature in Europe. The Tasmanian sun is ruthless, and its rays seem to burn deep into the skin straight away. Paradoxically, it’s partially due to the clean air, lacking the ‘filters’ of dust and tiny debris. On top of that, UV levels here are extremely high – you cannot feel it, but for fair-skinned people, 10 minutes are enough time to earn a sunburn. Yes, just before sunrise it’s rather chilly; windshields are covered with dew droplets and my friends are shaking over their morning coffee after a night in sleeping in tents, their clothes cold and wet from hanging outside all night. However, only an hour later, there is no trace of moisture left in the air. In the southern part of the island, the grass is pale from the heat. When we drive on Tasmanian dirt roads, clouds of dust bloom in the air.

One evening, dark clouds finally gather over the horizon. The first flash of lightning seems like a good sign. But even though it’s followed by others, and the sky thickens and purples, only a few drops fall onto the sand. It’s not the long-awaited shower, but the Tasmanian curse: a dry thunderstorm. The air absorbs the moisture before it manages to reach the ground. Embers that could have been easily put out by rainfall now spread into fires. Unlike those caused by humans, fires started by lightning bolts often take place in secluded, faraway places, impossible to reach by fire engines. The strong winds that come with the storm fuel the fires and can carry the embers even several kilometres away from the original blaze. But the worst thing about it is the vicious circle this causes: more fires mean less humidity in the air. The less humidity, the more dry storms. About 2400 lightning bolts hit Tasmania on 15th January alone, setting its forests on fire in 60 different spots.

***

When we were admiring eucalyptus trees in Mount Field, bushfires seemed a distant problem. We realize that we were very wrong as soon as we arrive at Lake Gordon. The dam on the lake is the pride of Australian engineers, and one of the most popular tourist attractions in Tasmania. This 140-metre-tall concrete arch cuts the landscape in half. On one side, a vast lake spreads, its waters so dark they almost seem black. On the other, we can see a rocky gorge with just a thin, winding stream crawling on the bottom. Tasmania is pretty crowded in high season, but on our way here, we drive by just a few cars. The free campsite nearby is empty. Instead of vans, campers and jeeps with tents on their roofs cramped one next to another, we can see just a few large, sluggish flies. There are notes left on the buildings: the campsite is closed due to its proximity to bushfires spreading uncontrollably in this area. We can’t swim in the lake either – army planes come here to draw water.

The campsite is located near Lake Pedder, a symbolic place for Australian ecologists. This small body of water, surrounded by swathes of sandy beaches, was for many years considered a local treasure. In the early 1970s, engineers came from hydropower companies, who wanted to fill the entire valley with water. Protests against the artificial enlargement of the lake caused an unprecedented mobilization of the local community. They didn’t succeed, but it led to establishing the first Green Party in the world, along with many non-profit organizations, such as the Wilderness Society that remains active to this day.

The new Pedder, over 20 times the size of the original lake, is beautiful, too, adorned with islands and bays that bite into the rocky shores. We are tempted to stay here for the night despite the camping ban – we could enjoy the empty campsite, go to sleep on the beach. But something about this picturesque view is unsettling: it lacks depth. Even the elements of the nearby landscape are greyish and fuzzy. When we get back on the highway, we drive into a thick mass of smoke for the first time. Following a deserted road with no signal (typical in national parks), we decide that the camping ban was not an unreasonable safety measure after all. Instead of sleeping by a mountain lake, we spend the night in a local village, behind a fire station. When we arrive, the car park is already packed. Headlamps illuminate the white flakes covering our clothes and sleeping bags. It’s ashes, falling from the sky.

***

Over time, we get used to the smell of something burning. Even having aired the car, we can still detect the distinctive smell on our clothes, bed sheets, upholstery. But the real uncanny feeling arrives when the sun comes out, small and aggressively orange. The devil’s sun, as some locals call it. The light filtering through the smoke is golden, casting that eerie haze beloved by photographers. But instead of lasting for less than an hour, it lingers from early noon until the blood-red sunset.

On 21st January, the air in the Huon Valley in the south of Tasmania is worse than in Beijing. In Geeveston, PM10 concentration reaches 250% of the acceptable amount, and PM2.5 particles soar to over 400% of the norm. In the slightly larger city of Cygnet, PM10 concentration is over three times the safe limit, and PM2.5 reaches it four times over. Cygnet, with its population of 1500, is a Mecca for Australian and foreign hippies. When we visit it a few days later, the walls are adorned with posters advertising the 37th edition of the nationally-famous folk festival, yoga class leaflets, and handmade posters calling for bringing capitalism to an end. The neat main road is lined with indigenous jewellery stalls, art galleries, pottery studios and herbalist shops – everything shrouded in a thick veil of smoke. Common sense tells us to keep going, but hunger wins with reason. We sit in a vegan sandwich store and watch other guests through the window. Two men sit outside next to their bikes and calmly drink their coffee. Next to them, a barefooted guy in linen trousers is reading his paper. Parents walk with their children. Nobody seems worried.

Part of it is due to the local mindset – Australians take pride in their pragmatic approach to life, rounded with a relaxed attitude and their ability to adapt to unfavourable circumstances. Bushfires are considered bothersome, but they remain a normal part of life, just like 40-degree heat, venomous spiders or giant pythons appearing in someone’s swimming pool. When the local daily The Mercury wrote an alarming article about Tasmanian air being worse than in China, some commentators were outraged. They accused the author of chasing unnecessary sensation and deemed the comparison ridiculous. 10 days later, the smoke from burning Tasmanian forests travelled over 2000 kilometres south, reaching New Zealand. The concentration of PM2.5 in Geeveston exceeded the norms 20 times over, and the Department of Health and Human Services advised the elderly, children, pregnant women and chronic patients to leave Cygnet.

***

Tom Allen from the Wilderness Society Tasmania insists that this year’s bushfires are not a normal phenomenon. In January, the organization published an open letter, declaring the recent fires just as natural as the dying coral reef or melting ice caps. “The fingerprint of climate change is all over recent bushfires in the TWWHA [Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area], which have occurred in 2008, 2010, 2013 and 2016, all of which have been caused by lightening strikes,” the report stated. “Around 13% of the TWWHA has been burned by bushfires since 2007. The frequency and significance of fires from dry lightening strikes has escalated dramatically since the year 2000.”

Scientists have been long saying that global warming means more thunderstorms. The consequences of dry storms are severe not only in Tasmania, but also in California, among other places. In 2014, a team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley established that for every additional degree in temperature on Earth, the number of lightning strikes per year will increase by 12%. In October 2018, scientists from the University of Tasmania in Hobart published a report on the causes and scale of bushfires in protected regions of Tasmania since the 1980s. The report shows that within just three decades, lightning strikes went from being a marginal phenomenon to the greatest threat to the island. Two months later, Tasmanians witnessed it firsthand.

***

In early February, Tasmania is still waiting for the rain to come. Professor David Bowman is a lecturer at the University of Tasmania and Director of the Fire Centre Research Hub (a think tank researching fires). He calls this month-long ongoing crisis an “unprecedented” and “historic” event. “We’re looking at a fire situation that’s now gone for a full calendar month,” he says in an interview with ABC. He adds that the scope of losses might be underestimated, because the fires didn’t do much damage to human settlements, mainly destroying forests. In December and January, only seven houses were burned, but at the same time, about 200,000 hectares of Tasmania were lost to fire – an area almost four times the size of Warsaw.

Another week passes before the rain finally falls and the temperature goes down a bit. By the end of February, the bushfires were more or less contained (although some hard-to-reach areas deep in the forests would keep smouldering until April). The board of the Tasmanian National Parks Association published the first report: roughly 94,000 hectares of UNESCO reserves had burned – 6% of all listed areas in Tasmania. On top of that, over 42,000 hectares of forests not on the world heritage list, but still within protected areas, were lost to fires. There was some good news, too: it seems that the most delicate species, which would stand no chance of growing back after the fire, were almost unaffected.

However, Tasmanian activists are far from relieved. “”It’s not accurate to suggest that only fire adaptive vegetation was affected,” insists Tom Allen. “Government sources frequently claim that damage is minimal because most of the vegetation burnt is ‘fire adapted’. They seem to be in denial about the catastrophic threat posed to alpine and Gondwanic vegetation. In addition, it is not desirable even for ‘fire adapted’ vegetation to burn at the height of summer, as intense fires threaten the very soils on which much of the vegetation grows. Areas of vegetation that have been in place since Gondwana, such as King Billy pine on Mount Bobs and tracts of old-growth Eucalyptus regnans, the tallest flowering plant on Earth, suffered serious damage. Because of climate change, it’s unlikely that the vegetation will be able to grow back. This vegetation has gone forever.”

***

By the end of March, Premier of Tasmania Will Hodgman announced that he would call in an independent body to examine the chronology of this year’s bushfires, and review the firefighters’ responses and the scope of losses. The experts make it clear that even if we choose the most optimistic approach and decide the catastrophe was avoided this time, Tasmanian flora might not be so lucky in the forthcoming years. Especially since the Australian island is not an exception. While Tasmanian forests were ablaze, the northern state of Queensland was drowning in mud – a result of heavy rainfalls after a five-year-long drought. In November and December last year, fires demolished New South Wales. An Australian non-profit organization Climate Council reports that more than 200 climate records were set over the three most recent summer months. Over that period, unprecedented heatwaves hit all Australian states: in Bourke in New South Wales, temperatures of over 40°C remained for 21 days in a row. In Rabbit Flat in the Northern Territory, the 40°C heatwave lasted 32 days, and in Cloncurry, Queensland it was there for 40 days. Thermometers in Melbourne, usually remaining on the chilly side, had shown 45°C.

Apocalyptic events took place throughout the scorching continent. Australians all over the country removed piles of dead bats from their lawns – a two-day-long heatwave had killed one-third of the Indian flying fox population. In South Australia, peaches and nectarines literally boiled on trees. A river in New South Wales became filled with thousands of dead fish. The bodies of 90 wild horses were found near a dried-up waterhole. They had all died from thirst.

This pristine island, known for the cleanest air in the world, is ablaze.