You can’t sell anything to a sleeping person. So, from the economic point of view, sleep is unprofitable. It is the last frontier of humanity, which protects us from the deluge of consumption.

I can’t tell whether it’s night or morning, or which consecutive day, entangled with darkness, it is. The twenty-first. For the twenty-first time, I wake up in the artificial bluish light, the air-conditioned atmosphere, among the quiet murmurs made by people in other capsules. We care about the etiquette of noiselessness and anonymity. Our smiles, exchanged in the shared bathroom and at the large dining room table, express a kind of désintéressement amid dim sums, pickled ginger, and the flash of screens that we watch far more intently than each other. Like all the inhabitants of this metaphorical space station, who rent a small closet, a niche with a bed, an electrical outlet, and a sliding laptop tray, I feel light, unconnected, timeless.

The reduction of private space, the removal of darkness, the absence of smell, and the uninterrupted connection to the internet lulls us into a gentle, intoxicating stupor. We succumb to the illusion of an infinite present. I have managed to forget how old I am, if anyone is waiting for me at home thousands of miles from here, and whether I’m planning to go somewhere else. I think of nothing. I exist—at least I think I do. Sleep deprivation is taking its toll; I’m tired, I don’t feel hungry, nothing affects me at all.

Astronauts, whose bodies and minds can’t rely on a circadian rhythm, enter a similar state. Bereft of gravity and time-allocation derived from nature, they experience deregulation. Except that I happen to experience weightlessness on Earth—in Singapore, a city perfectly automated, surrounded by devices ready to satisfy most of my needs all the time. Its citizens spend the least time sleeping of all humans. Not much over five hours a day. Life here is a sample of a future when there is no more sleep.

Money doesn’t sleep. When stock markets in Europe and Asia pause, the one in Singapore produces financial facts for the following day. At that time, the smartphones of managers and brokers quietly vibrate on the bedside tables of the Western Hemisphere, collecting valuable information, which a hand will reflexively reach for right after awakening. Bodies adjust to the rhythm dictated not by dawn and dusk, but the electronic environment. Fewer and fewer of us sleep truly deeply. More and more of us only move to shallow immersion, the equivalent of stand-by mode on devices. And those aren’t actually turned off anymore, just switched to silent or sleep mode. Together, we remain on standby for regular information and software updates. Researchers are alarmed to observe that more and more people wake up at least once during the night to check messages on their smartphone. We are thus mimicking the “behavior” of technology—we perform automatic refreshes. We never cease to work over our mobile identity, one of many. Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman warned that it would be an occupation devoid of breaks and rest.

Singapore is particular because it collects financial assets only comparable to those of Switzerland; it serves capital. It is not so much a city, as an urban scenography created to serve the needs of banks—its advantage in the past lay in its great location connecting different regions of Asia. Nowadays, it has no importance because the internet has eliminated travel and the time needed for it. Money, freed from its physical form, moves faster than humans. Therefore, humans must adjust to the elimination of time.

The Compression of Time

That’s how, in its pre-packaged version, late-phase neoliberalism is striving to appropriate the last unmarketized sphere of our life: a night well-slept. According to Professor Jonathan Crary from Columbia University, sleep is the last to defend itself. The other aspects of humanity—thirst, hunger, lust, the desire for intimacy, have already been colonized by capital. These needs are artificially fueled and equally falsely fed. In his gloomy essay, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Crary argues that Western capitalism (regardless of the part of the world in which it is de facto practiced) effectively conquers those areas where we are already merely subjected to uniformity as consumers, rather than complex and distinct citizens. This process is, in his opinion, connected with compression of time. To buy and use goods and services, we need to minimize the time needed for exchange, and, what follows, to eliminate “unnecessary”—according to market appraisals—minutes, hours, and months devoted to the process of reflection, consideration, and decision making. It’s best to replace it with a short pathway; stimulus-response. Transactions should occur instantaneously—it’s the best option from the profits perspective.

The urban environment, historically created precisely to speed up and facilitate exchange, for stimulating trade and markets, is presented by the American art critic and theorist as a laboratory for just that kind of rapidly advancing process of compression. Right now, only one bastion remains: sleep, seen as the privilege of dreaming, the last area of unfettered imagination, and also the only still-open door to the future. If we lose it, nothing more awaits us except the intensified here and now. In this light, we should protect sleep and dreaming from the dictates of consumption as an inalienable human right.

A Soldier Who Doesn’t Sleep

Economically speaking, sleep is unprofitable, it cannot be assigned any value, nothing can be negotiated with us when we are disconnected and inaccessible. Therefore, the market wants to get rid of it. The point of reference to Crary’s considerations are experiments by American military agency DARPA, which for the last few years has been trying to “create” an unsleeping soldier and has been conducting sleeplessness tests. Such a soldier would not only make a perfect warrior, keeping pace with the drones bombarding Afghan villages in the middle of the night, but would also become a prototype of the future consumer—one who incessantly spins in the cycle of acquiring goods and services, never stopping. Crary’s concern is not without reason. Sooner or later, military innovations find their way into civilian life. The most significant example of this is the internet, the main culprit in the flattening of time to one never-ending moment.

The loss of sleep would be dangerous for humanity because it would mean a farewell to a deeply hidden mystery, the inscrutable region of our psyche, as well as the power of imagination. Without the time assigned for rest and quiet, the turbines of fantasy wouldn’t be able to start. It would be impossible, therefore, to conceive of a time different to the one that is passing right now. We are arrested in a present, which merely imitates constant renewal and rejuvenation. Crary notices an interesting interdependence between people and objects. They, after acquiring their improved, newer versions, reinforce an apparent change (usually exaggeratedly described as groundbreaking and wrongly compared to key inventions, such as the wheel). The truth is, however, that things are more and more undurable, serve us for a shorter time, and don’t generate anything by their appearance or disappearance. Their only serious effect, according to the researcher, is that they force us to adapt to this way of understanding time; compressed, devoid of memories and the feeling of passing.

Time Flies

This change is reflected in language, particularly the urban and new media one we use to denote our relationship with time. Nobody says that time passes, or flows, or that “time will tell” anymore. We say, “Time flies!” Or, “I didn’t even notice!” Or, “I don’t have time.” No one has it, because everyone is chasing after it—like a fleeing deity, priceless as an exhausted natural resource, which had been swallowed up by the greedy machinery of the consumer industry. Commodified time belongs to the sector of fast-moving goods—if it’s there, it’s very quickly utilized, used up, taken. Thus, it disappears.

It is not very hard to feel this drastic change for a Pole who has kept in mind those dragged-out afternoons and long evenings measured by the clocks of the socialist era. The arrival of the free market meant—most literally—acceleration. Longer working hours, extracurricular activities, and a pervasive sense of haste. Time became the terrain of competition and rivalry. Whoever had (free) time was a fool. Whereas, the winners quickly assimilated the maxim that time is money. I shorten this complex process to its most primitive effect, because while writing this text I’m also in a great hurry. And I’m amazed that you’ve found the time to read it.

On the twenty-ninth day, still sunk in my Singaporean torpor, I decide to radically change my perspective. I take an elevator to the fifty-seventh floor of the Marina Bay Sands complex. There, on the roof, in a bar near the infinity pool, I look down on the headquarters of major banks and financial institutions. Soaring skyscrapers decorated with branded neon lights shine brightly, uncannily. Over the non-sleeping non-place, there rises a multicolored glow, which in a moment will turn into a pale pinkish dawn. Under my feet, there spin roulette wheels in a luxury casino, and in the most expensive nightclub on this planet, the owners of vast fortunes and sports cars—particularly loved in the island country—enjoy themselves. The night favors the rich, wealth likes to look at itself in the blaze of lights. Illuminated skyscrapers have been the icons of triumph and tomorrow for over a hundred years. They’ll go off just before dawn, and the morning joggers will be witnesses to this anti-spectacle.

A few years ago, the inhabitants of hyper-capitalist cities could not live life to the fullest—only working too much then sleeping it off. But the market taught them to squeeze the most from the day, without interruption. Here in Singapore, international expats are active before sunrise. They exercise and run, keep fit, brushing away all signs of “wear and tear,” staying smooth and new as the last iPhone model.

After dusk, oysters are placed on ice platters, corks pop, and colorful lasers go up into the sky from the roof of the Marina Bay Sands. Let them know up there, in outer space, that we’re not asleep.

The American Dream

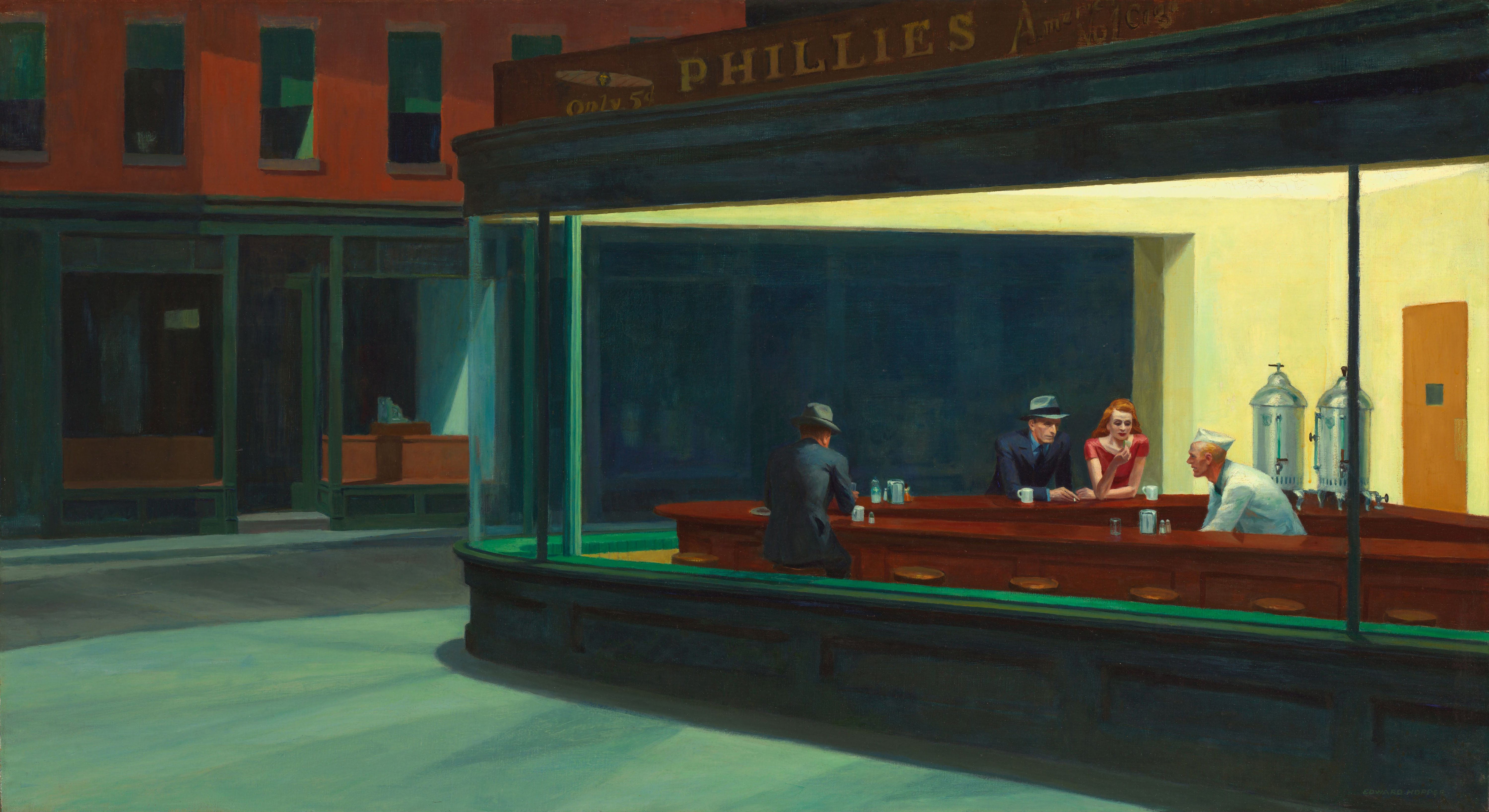

“I want to wake up in a city / That never sleeps…” Frank Sinatra croons dreamily in “New York, New York.” The hit song tormented me for nine sleepless, winter nights, while warding off jet lag with long walks through Manhattan. The almost always-open venues meant I was safe at all hours. It never crossed my mind to be afraid of anything. The presence of people and lively businesses feed off each other—noisy, brightly-lit cities are also less threatening. Contrary to the apparent global policy of now removing bars and nightclubs from city centers for allegedly causing anti-social behavior, many studies and surveys support the claim that neighborhoods full of people, even those consuming alcohol, are safe. The residents are the most effective social control mechanism.

The harder the icy-cold wind blew, the more effectively it drove away my American dream. I roamed from a pizzeria to a bar, then again to a tiny gallery, and a sandwich shop alley. Everywhere on TVs under ceilings, I watched the replays of the Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama debates, where the Illinois senator comprehensively beat the former first lady. The year 2007 was coming to an end. Now, I am convinced that even in New York—the mother of all sleepless cities—time back then was less dense. The night dragged on, and to fill it was quite a challenge. These days, we would spend it with our eyes on personal screens, without even noticing the neon sign above a store window has gone out. The internet has fundamentally changed our perception of the passing minutes and hours, mostly due to the delivery of more content and stimuli in a small unit of time—it’s so overcrowded, saturated with competing possibilities; it’s always insufficient, virtually nonexistent.

This American metropolis gave birth to the 24/7 myth. It identified the nightly illumination of skyscrapers with success, and sleepless streets with endless possibilities. New York has an unmatched number of late-night establishments per capita. Yet, contrary to its mythical status as an insomniac city—perpetuated by cinema and popular culture—it’s metropolises that are far less regulated and with a higher rate of poverty, like Cairo, Dubai, or Montevideo. And this is because—contrary to the legend of Manhattan—it’s still mostly those who are trying to survive, and not those who are trying to reach the top, that have no time for sleep.

The Three Steps to Sleeplessness

The fairy tale about a sleepless metropolis was brought to reality by three technological achievements at the end of the 19th century: reinforced steel, from which frames for up to a hundred-storey buildings were made, electricity, and elevators. The telephone was also important. Thus the skyscraper was born—a construction artificially intensifying life, divided into floors—worlds that can function irrespective of time of day and weather conditions. They were universes, cut off from each other and unrecognizable from outside, due to being covered with a monotonous facade, but on the inside interconnected by communication routes—elevators and phone lines. The skyscraper has become not only a temple of commerce, but also a time compression totem: a simultaneous answer to many needs, independent from reality. It drew the consumer for many hours, on the inside time ran differently and gained a concrete value. The philosophy of profit connected time with space, initially tempting people to come to places where markets were functioning, and later, due to the development of mobility and virtuality, it was the markets that started to expand in time. The one that we used to spend elsewhere.

Late capitalism seeks to level out this inaccessibility and get rid of the concept of “elsewhere.” There is no contradiction now between, say, lounging on the beach with your family, and buying a new dress. Lying down, you squint against the sun, brush your finger over the smartphone, and it’s done.

There is also no question of freedom from consumerism, as long as your eyes are wide open. Sales are conducted everywhere, if only in high flying airplanes, cutting through time and tax zones. Trading takes place at airports, which are alive, even gaining momentum at night, like the ones in Dubai or Qatar. Imitating cities in their radical, timeless variety, they’re designed to have avenues and central squares, to give the illusion of diversity and natural landscape. There are palm trees and green spaces, chapels where you can get married, restaurants with gardens, and conference rooms pretending to be central business districts. There are also hotels providing a home for an hour or twenty-four, and above all—stores. Exposed and located further from rest areas to keep passengers moving, in acquisition mode.

Airports are making so much profit that it’s now being considered to locate them, not on the outskirts but in the heart of the city. This would be the adequate illustration of John Crary’s prognosis—the service center pulsating continuously, and interconnected with many others like it. The World Wide Web materialized.

Tokyo Light Pollution

It’s the middle of the night, I’m lost again. I rose to the surface of Tokyo through one of the fourteen exits from the subway station and froze. The architecture does not suggest the direction, it rather sends a message: “Go anywhere, the city is everywhere.” A thin boy in skinny jeans is trying to help me find my way using Google Maps, but in effect we both feel more confused. He walks away, bowing, and I let myself be tempted by lights. I’m standing in the middle of an arcade, terrorized by the noise of machines and bright, flashing bulbs. There are dozens of devices here, the majority are for the ball game, pachinko (パチンコ). Most of them are already occupied by customers of different ages, from teenagers to pensioners. They can’t see the world beyond their score, pressing and pulling at knobs; clicking, snapping, and shooting, then adding more tokens and coins to the slots. All I see is backs, blinking congratulations, or alarming signals that the game is over.

A blinding light joins the deafening noise. The patrons in this room don’t pay attention to either—as indifferent and robotic as the machines that drain their money. This phenomenon is explained in different ways—the need to recover from long work hours, or an attempt to cover up loneliness. Tokyo is a metropolis which has long left behind the shock of the future. It experienced the fever of reaching that finishing line about forty years ago, then bound people’s lives with the functioning of machines into a single, inseparable organism, and now they are aging together: A Japanese society full of pensioners and the infrastructure of an outdated tomorrow.

Tokyo leads in the ranks of cities with the highest degree of “light pollution.” When it came ablaze with lights in the 1880s, it was seen as a manifestation of the triumph of Asia over Europe. The Japanese quickly fell in love with the night culture of commerce, street fashion, and entertainment. As a result, they quickly raced forward, and in less than a hundred years became the market model of sophistication and development for other cities. But this was achieved at the expense of sleep. Crary relates sleep deprivation to the inability to imagine what’s next; perhaps, the country got stuck because its inhabitants don’t dream.

Everything here works in the inverse to what I’m used to. I also sleep for a short time in Tokyo, early at dawn or during the day, and at night I move, eat, and meet others. I did not make that choice, it was the city that set the rules of the game. I eat breakfast before dawn, at one of those twenty-four-hour stores where they sell freeze-dried noodles, pour boiling water over them, heat up ready-made vegetables in a microwave and slurp it all shoulder to shoulder with an equally awake neighbor. He probably lives in the area, in one of those micro houses, where cooking is too cumbersome, and acutely lonesome. We don’t even need to talk, it’s enough to just be—us and the assistant behind the counter. And on the other side of the street, there is a machine selling drinks and cigarettes. It has a backlit display window and stands like a toll road for keeping the local civilization going—a sign that all is as it should be. Vending machines sustain Tokyo inhabitants craving a soda and rice sandwich, and serve as both points of orientation in a city of confusing addresses and as social microcenters, at any time.

I get on the subway, I don’t know which time of the day, and observe people skilled in train naps. They close their eyes and sink slightly. Even when the coach jerks, they can still keep their bodies from touching other people. Later, eyes open a few seconds before reaching the right station—get up and disappear.

It’s dawn when I arrive at my hotel. The room is bright; the neon city tries to break through the drapes. I don’t believe I can fall asleep. And yet I dream: I’m riding the subway and can’t get out. I can’t find an exit at any of the stations. Wandering, I travel further, and encounter more phantom exits. Along the way, I’m tormented by flashing, multicolored advertisements for depression, as if it’s recommended as a desired state, taking on bright colors. It’s announced by the railcar speakers. Another station, another blind passageway.

Sleep Deprivation as Torture

According to Jonathan Crary, the bastion of sleep has already been eroded. True, we still sleep, but not so well. And for a certain price. Every year, several million Americans buy sleeping pills and sedatives, without which they wouldn’t reach a state of rest. And lack of sleep causes depression. The professor claims that for more than a century—since the publishing of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams—sleep has been subject to individualization and rationalization. The attempts to read the meaning of these nighttime visions, to draw out the secret processes of our psyche, could constitute an attack on what is unexplained, and thus impossible to buy and sell. Crary sees in it the cult of individualism, that accompanies neoliberal doctrine and puts the needs of one person above all else. If we are segregated into discrete units, we can be sold more, removed from communal defense mechanisms, and most importantly, from not-for-profit community exchange. On our own, we are more prone to temptation—and being broken.

For hundreds of years, depriving prisoners of sleep, exposing them to glaring light and noise, has been one of the cruelest forms of torture and most effective way to extract information. It is enough to deprive a person of assuming a comfortable body position, shine a light in their eyes, or torment them with sound for hours or days, to induce psychosis, anxiety, and total submission. Two or three weeks without sleep can cause death.

The effects of being forever in a typical urban environment—overexposure to light, noise, and notorious sleep deprivation—comprise a long list. It includes impaired metabolism, restlessness, altered heart rhythm, higher cancer risk, proven in examples of night shift workers, as well as the harder-to-study compliance and uniformity. According to Crary, the elimination of time and sleep is a key ingredient in removing differences between people. The market needs ideal consumers, always active and predictable.

Home is Where Wi-Fi is

The clubs in Hongdae, Seoul’s university district, haven’t closed yet, but intimate coffeehouses a few minutes walk away are already warming up their espresso machines. The transition between night and day is smooth, and there’s no need to return home. As in Tokyo, here too one can sleep, for a small fee, in a capsule hotel, a hostel, or an internet café, use the shower, get changed, and join a quiet crowd, surrendering to morning oblivion. Night drinking to the point of unconsciousness, crazy dancing to music played in the street, laughter at full volume, are being erased. The ride to the office or school is taken in silence, face-to-face with our own smartphones, dressed to the nines. Clothes shopping also happens at night. Refreshing the wardrobe is like brushing your teeth—a daily activity. Before the sole of a shoe has time to wear out, and the trim of a jacket can fray, they’ll be replaced by a newer version. People do the same to each other. Yesterday’s events are lost like a lizard’s tail. There is no past, and there is nothing but perfection—facial plastic surgery is routine, there is one ideal and the collective strives towards it in unison.

So what good is the sense of being settled; of coziness and comfort, which must be associated with suspension, inertia? There are no homes here, only apartments, where you spend only as much time as you need for brief recuperation. A journey to a far-flung district from the center of a vibrant, underground city of interconnected subway stations, which entertains, feeds, and revives during brightly-lit nights, seems like a waste of a life.

I’ve lived here, as in Singapore, for a month. In a hostel, right in the middle of a youth-filled neighborhood. For fellow wanderers, I have distinguished Russian programmers and New York neurotics. They are all on the road, because they don’t want to be home. Soft beds in shared rooms, with small private reading lamps, and unlimited internet. Forever hopping from country to country, their rule of thumb is that home is where wi-fi is. It’s night beyond the window. On the rug in the lounge, a few guys are playing computer games, some Australians giggle in the upstairs library, a woman swigs some rice vodka then winces in disgust. We go to sleep late, eat breakfast in the afternoon, go to the movies at one or two in the morning, if we can get tickets, because these are the most popular screenings.

Everyday I expect to collapse. I listen to my own heartbeat, looking for symptoms of weakness. Not quite. As it turns out, you can do that. For weeks, I haven’t felt any worse. I traded insomnia for a few naps punctuated by virtual sessions. Every time I wake up, someone in the room has their computer on—I hear the quiet clicking, not the silvery glow from behind the dorm bed curtain. We all have the same syndrome—our biological clocks have capitulated, now we operate according to a different rhythm.

The change was efficient and seamless. I don’t know when I ended up on the other side. The last time I dreamed was on the way to Seoul, not after that. I remember, I was sitting in a glass cell, under the ceiling of a large building. People were climbing up the stairs to see me. We were separated by a smooth pane, outside they laughed, waved, and talked. Motionless, I was only a silent spectator. It’s the future Jonathan Crary fears. Humanity settled in a city of uninterrupted wakefulness. Exposure to the constant flow of images, deprivation of agency. A ban on lowering the eyelids and dreaming of a different tomorrow.

Translated from the Polish by Irena Kretowicz