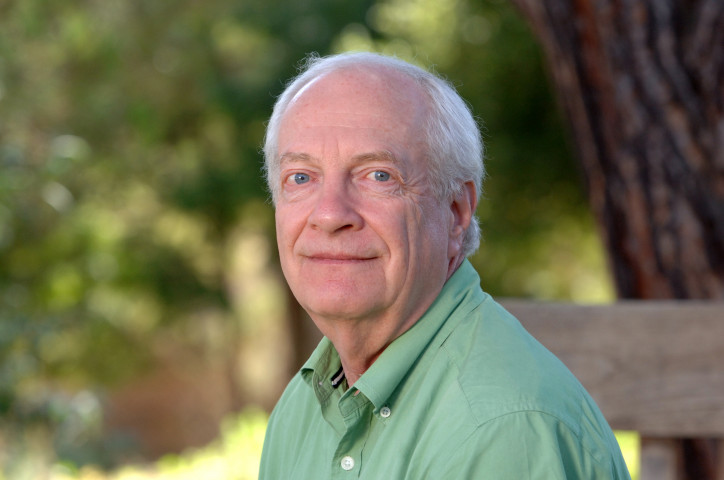

It all began with an overbooked flight, which led to me flying to New York on the Tuesday instead of the Monday. I didn’t really quarrel with LOT Polish Airlines, because my meeting with Allan Horwitz – whom I had been waiting for years to interview – was scheduled to take place on the Wednesday. Horwitz is one of my intellectual idols; I devoured his books The Loss of Sadness, What’s Normal? and Creating Mental Illness. Anyhow, I e-mailed the hotel to let them know that for unforeseen reasons I would be arriving a day later.

However, when I finally arrived at the hotel the following day, after a three-hour long drive (because of extremely, even for New York, heavy traffic), I was completely jet-lagged and knackered. If this wasn’t enough, it turned out that they had never received my e-mail and thus my booking had been cancelled. “We don’t have your room and there’s nothing you can do about it” is more or less what I heard from an extremely unfriendly receptionist.

With nothing else to do, I headed off in search of a new room. This took me another three hours. Unfortunately, a huge ventilator installed next to the window – a hellish device, which kept buzzing even after I pulled the plug out – prevented me from getting any sleep at all.

Despite all this I tried to stay confident, and on Wednesday morning I walked to the Port Authority Bus Terminal to catch a bus to Princeton. After spending a few minutes in a building that looked as if it was taken straight out of Franz Kafka’s nightmares, I just wanted to run away. Hundreds of platforms, thousands of people rushing to different places. A crowdy, noisy and chaotic place. Which bus am I supposed to get on and where should I go?

Finally, I managed to board the bus and get to the meeting point. After 36 sleepless hours, I managed to arrive at the porch of a lovely, wooden villa. I was exhausted and sweaty because of the horrible heat and the humidity in the air… there’s no doubt that I could have looked exactly like your everyday eccentric. Yet I also wouldn’t have been surprised if, as a result of the previous day and a half, I was just hallucinating and, after opening his front door, Horwitz didn’t actually look at me with a hint of surprise, or even concern.

It is common knowledge that the best way to divert attention away from one’s own mental state is to become interested in the interviewee’s mental state. This works especially well if the interviewee is a prominent sociologist, who on a daily basis deals with such concepts as illnesses, health, disorders and norms. Which is why once we sat down in the living room, I immediately cut to the chase.

Tomasz Stawiszyński: Do you consider yourself a normal person?

Allan Horwitz: Oh, absolutely not [laughs].

It’s not a surprising answer.

Obviously, the term ‘normal’ has a large range of applicability, but – let me back up – in the way that I would define normal, then yes I would say, I’m normal; normal meaning not disordered. I don’t think I’m disordered, so therefore I would consider myself normal. But if normal means typical, or statistically normal, then absolutely not.

What is your understanding of the term ‘disordered’?

Well, we talk about mental disorder and normality – but there’s clear cases on both sides, with sort of a broad fuzzy area in between. So while it’s possible to define clear cases, most cases probably don’t totally fit that. I think that clear cases would indicate that there’s some sort of dysfunction in a natural apparatus – and that natural apparatus could be perception or motivation or cognition or emotions – which prevents a person from acting as that function is designed. I guess, ultimately, you have to invoke evolution as the driver of the design, so that there’s some dysfunction of a natural, emotional or mental process.

But there are a lot of socially-constructed norms and ideas that are problematic in the context you mention. It’s hard to define it as evolutionary-based, for example, because these norms and ideas are precisely made in certain cultural contexts, and they change across time.

Here I would have to invoke my collaborator Jerry Wakefield’s concept where he defines mental disorder as harmful dysfunction; where the dysfunctional aspect is really based on natural design, but the harmful aspect stems from social definition. To have a mental disorder, you would need both aspects, both the dysfunction and the harm. Neither one is sufficient in itself, but both are jointly necessary.

And how would you define the main social forces behind the systems of norms, the ideas of mental health? What is the core social context that produces these kinds of ideas?

In the modern context – and certainly all societies have some notion of mental disorder, it’s a universal concept – the mental health professions and especially psychiatry are at the core of definitions. Yet psychiatry itself operates in a web of social and economic and political forces. Currently, the ideology of science is a necessary component – any profession now has to say that they adhere to scientific norms. You can’t be a professional without claiming that you’re scientific, that just won’t fly culturally. It’s also embedded in an economic system, where, certainly over the past few decades, the pharmaceutical industry has been incredibly important in shaping psychiatric conceptions, collaborating with the psychiatric profession, providing money to the psychiatric profession so that the status of psychiatry in medical schools has really been greatly enhanced. Although that is now on a much shakier basis, because all of the extremely profitable drugs are no longer under patent. The lucrativeness is declining, there doesn’t seem to be any sort of new drugs on the market, and really there hasn’t been any genuinely innovative drugs since the 1950s.

We think about psychiatry as an objective field of medicine, something that is the same as oncology: doctors diagnose diseases and prescribe drugs. But when we start to read your work and think critically about psychiatry, we realize that we are looking at something that is rooted in a very complicated web of economic, social and cultural issues. Do you think that psychiatry is really a part of medicine?

In a social sense, yes. In that they, psychiatrists, are in academic departments in medical schools, they possess medical degrees, they prescribe drugs that only medically-trained professionals can prescribe. From a social perspective, it’s obvious that they are. But there’s clear distinctions between psychiatry and almost every other medical field, which is that there are no objective tests that can go beyond a psychiatric judgement. The diagnostic process in psychiatry is fundamentally different, because that’s all that exists to say whether someone has a mental disorder. There are no heart monitors, there’s no blood monitoring, there’s no X-rays, there’s no tests whatsoever that can validate a diagnosis of mental illness. I’m doubtful whether there will ever be, but certainly at present, there’s just nothing like that in psychiatry. That really makes the practice of psychiatry fundamentally more subjective than other branches of medicine.

But at the same time you’re not a radical anti-psychiatrist like Thomas Szasz, for example, who just thought this was contradictory, the idea of mental illness in itself.

No, I’m not anti-psychiatry, I just try to describe the situation. I try not to impose my own values, and I think that the vast majority of psychiatrists are well-meaning and try to help patients. They have no choice but to portray psychiatric knowledge as more objective and scientific than it is.

There was a ‘tradition’ in sociology to look at this whole cultural area where psychiatry and psychotherapy is the leading force for thinking about the human self and our development. The sociologists used the term “therapeutic culture”. Philip Rieff was one of the first.

One of my heroes.

Mine too. Do you think that this is still an actual diagnosis of our culture, that we are living in a more and more therapeutic culture and society? That the language and the hierarchy of values and the ideas of psychiatry and psychotherapy are the main leading forces in modern culture?

Well, yes and no. It really depends on what trends you’re looking at. On the one hand, I think Rieff could look at current culture and see it as being highly exemplary of what he was talking about. ‘Psychological man’, although of course we wouldn’t use that term any longer. Trauma now is everywhere. Trauma, which wasn’t a major concept when Rieff was writing, but now everyone is traumatized…

…especially on the campuses.

Yes, especially on the campuses [laughs]. Everyone has more anxiety and depression than ever before, and the use of therapeutic language is very widespread. That would be very congenial to what Rieff was talking about. But there’s also counter trends. Sexuality is probably the best example of being non-medicalized; where the realm of what’s considered normal has expanded, and the realm of abnormal has… I mean now, aside from paedophilia, there is very little sexuality that is seen as abnormal.

But at the same time, we have this interesting thing, which was very much present in recent discussions about the #metoo movement, for example. In a way, sexuality has become a field that is very much related to trauma first, and then perceived as dangerous; as something that is very fragile, that we need to be very careful with. We are now negotiating the borders between what is sexual violence, what is sexual offence. It’s like the reverse of the sexual revolution.

That’s a very good example of where normative sexuality is seen as toxic, whereas in the past what would have been seen as anormative is now not described in terms of being ‘disordered’ or ‘not disordered’. As you say, the traditional masculinity would be the toxic aspect.

This is very political and I wanted to ask you about this merge of politics, psychotherapy and psychiatry. What are the roots of that merge, and how do you perceive this – as good or bad? Or maybe you don’t think about it as good or bad at all.

Well, I try not to. It’s hard to be completely neutral about that. I think there are minority voices critical of therapy culture. Therapy culture is widely seen as almost an unambiguous good. Certainly, for all the mental health professions, it’s more clients for them – that’s where their business comes from. In contrast to the past, involuntary psychiatric treatment is almost non-existent. So people seek help themselves. Trauma is a great generator of clients. Certainly in the United States and in other Western countries, having a mental illness diagnosis brings great benefits to someone. PTSD would be the prime example. There’s an astonishing statistic where 99% of veterans who have a diagnosis of PTSD maintain that diagnosis the following year. Nobody gets well, and it’s pretty clear why. Here I can’t help but let my scepticism creep in – they get pretty well-compensated for keeping the diagnosis, and if they don’t have the diagnosis then there’s no more compensation. So it’s a tremendous incentive to remain mentally disordered.

Why did it become so common, so popular, so widely-represented? Is it also related to the politics of big pharmaceutical companies who develop drugs?

That’s what’s so interesting about the PTSD case. It’s unusual in that there are no established drugs for PTSD. Unlike, say, depression or bipolar disorder or anxiety conditions. Those were all promoted by the pharmaceutical companies. PTSD to a much lesser extent.

When we look at it from the social perspective, maybe this is a process of – and you write about this in your book Creating Mental Illness – shifting some social issues to psychiatry. In America, there was a huge social problem of veterans after the Vietnam War. Then we see the process of medicalization of this syndrome, creating this category, and then it comes into the field of psychiatry.

Although PTSD is probably less centred in psychiatry. It has its own trauma specialists, who are sometimes but certainly not always psychiatrists. So PTSD, in that sense, is probably an outlier.

What do you think the cause of this phenomenon is? What cultural processes are behind it?

Trauma culture is one major aspect, but historically military institutions completely resisted trauma culture. It’s the opposite of the values they promote. It’s cowardice, whereas courage is what military culture is built on. But really the widespread opposition to the Vietnam War in the 1970s, the ultimate creation of the PTSD diagnosis in 1980 in the DSM-III, then it got – and this gets somewhat complicated – it got appropriated by the feminist movement. Initially, many feminists promoted multiple personality disorder. It had a career of about 10 years before it became completely discredited, so that PTSD became a much more acceptable diagnosis for the feminists.

Why?

Because the multiple personality case turned out to be created by the therapeutic culture, created by therapists who firmly believed in its reality, but the cases became more and more bizarre. The number of selves multiplied to people having 20 or 30 distinct selves. The real reason for the demise of multiple personality disorder was that parents began to successfully sue the therapists of the children who had received these diagnoses. And it was widespread in nursery schools where small children come up with these fantastic stories that couldn’t possibly be true… It defied all sense of reality, so it became completely discredited. PTSD became a far more respectable diagnosis.

But why was multiple personality disorder an attractive idea especially for feminists? Maybe it was useful politically?

The perceived generating forces were sexual abuse by fathers at very early ages. So, in one sense it fit the traditional psychoanalytic narrative by casting blame on the male, on fathers. It was an attack on the patriarchy at its most basic level, of fathers abusing daughters, which for a very brief period of time resonated with cultural narratives.

When we look at the history of psychiatry, we observe that at certain moments there is a lot of diagnosis of some disorder. Then it shifts and another one becomes the leader. You write about it in your books, that at a certain time when psychodynamic psychiatry was the basis for the DSM – the first and the second editions – fear and anxiety was the most common disorder or symptom. Then depression comes after. This huge epidemic is correlated with a paradigm shift in the DSM thinking of what a mental disorder is and how to diagnose it. At the same time, we’re still developing new drugs for this syndrome. I would like to ask you about this epidemic of depression. We hear about it a lot, that depression is one of the most diagnosed diseases, that we still have an epidemic and it will grow and grow. But you look in The Loss of Sadness at this phenomenon from a totally different point of view. The book was published in 2007, 12 years ago. How do you look at these things after 12 years?

You put it very well, in the 1950s and 1960s, anxiety is everywhere. Then with the DSM-III in 1980, they tore anxiety apart, they made it into nine completely separate disorders. They did exactly the opposite with depression, where they put together previously distinct psychotic depression, melancholic depression and just ordinary neurotic depression. The criteria for depression were things like sadness, loss of appetite, fatigue – the most general kind of symptoms qualified. You only needed to have the condition for two weeks to get a diagnosis, but for most of the anxiety symptoms you needed six months. So it just made much more sense, it was much easier to diagnose depression than anxiety. Then the SSRIs come along at the end of the 80s. They work very generally in the brain to raise serotonin. Theoretically, they could have been marketed as anti-anxiety drugs, but that made no sense as those drugs had been discredited. Depression was the new kid on the block; the drugs are called anti-depressants and are wildly popular. That probably leaves the story roughly at the early 2000s…

There is a book written by Peter Kramer in the 90s, Listening to Prozac, where he discusses Prozac as some sort of a holy grail that will make our lives better. Not only as a cure for diseases, but that it’ll make us better people.

Yes. That would have been published before I was writing about these issues. But now the major development is that the SSRIs have lost their patents. They can now be generics; they’re no longer nearly as profitable as they once were to the pharmaceutical companies. The pharmaceutical companies did develop a drug that they marketed in the United States as a new anti-psychotic, Seroquel. Cymbalta, which was previously for bipolar disorder, now becomes a shiny new toy. But even those drugs are now pretty much off patent. Certain anxiety conditions have sprung back to life, like social anxiety. So the whole marketplace changes. Right now, there doesn’t seem to be any major drugs in the pipeline, because there’s marijuana, mushrooms, ecstasy, ayahuasca, LSD. This is playing out right now, and it’s very hard to know what will happen.

One of the most interesting parts of this may be another changing paradigm in thinking about mental disorders, which is very much present in the commencement of experiments with psychedelic drugs – that, actually, perhaps the substance is not so important? Rather than the substance that you lack in your brain or your nervous system – which the medication then replicates and is perceived as having cured you – we have the experience. This psychedelic, mystical experience changes your inner world, the way you experience things. This may contribute to thinking in a completely new way about psychiatry.

The other aspect is that unlike the traditional medicine that you take every day, you don’t go on an LSD trip daily. You take it and if your trip is successful, it’s probably going to alter your subjectivity for several weeks. You can take it occasionally and not daily, as you do with commercial drugs.

Do you think that maybe that’s why traditional psychiatrists are so sceptical of these ideas and experiments? In a way, it is against the whole infrastructure, the whole psychiatry business and how it works today.

I don’t really know what clinical psychiatrists think of this. Many academic psychiatrists seem quite intrigued by these experiments. Ketamine is the other new one. Not long ago it was this sort of date rape drug, or at least a party drug.

Let’s go back to what you mention about changing the core symptoms in diagnosis. How does it work? Does something change in culture, independently of the psychiatry field, for example, and they just get together and look at what’s going on, what people experience, and then write these DSMs to describe what’s going on? Or maybe they work in the opposite way. Ideas change in psychiatry, we have a completely new way of thinking, and then we just attach people to these new categories?

I think both dynamics are at work. In the case of anxiety and depression, it was almost completely internal developments within psychiatry and psychiatric theory, where anxiety initially is seen as generating all neuroses. So anxiety is the basic phenomenon. That turns out to be the core principle of psychodynamic thinking. Then when the more research-oriented psychiatrists come in, they don’t like that way of thinking at all, because it emphasizes unmeasurable, unconscious processes. It de-emphasizes symptoms. They want to have something that you can measure on the surface. They wanted to basically get rid of anxiety in the way that it had been conceived by analysts, and substitute depression as a measurable, symptom-based entity. But then, totally separately, that happens at the same time that these new SSRIs are being developed. They could have been seen as anti-anxiety drugs, but it just made much more sense to market them as anti-depressants. That sort of propels depression into the culture, and not anxiety. It’s a curious culmination of developments within the psychiatric profession that are then taken advantage of by the drug companies.

PTSD is a completely different story. That was unusual in that it’s an unusual psychiatric diagnosis, because there was no push from within the profession. It was that veterans of the Vietnam War wanted a diagnosis. They did have some anti-war psychiatrists as allies, but they prevailed over the conventional psychiatrists. So that was an unusual example of outside forces basically creating a new diagnosis in the DSM-III that turned out to be wildly popular.

What might be the deeper cultural consequences, existential consequences even, of the processes you describe? In The Loss of Sadness, you write a lot about expelling normal sadness outside of culture, and about pathologizing the normal human reactions to different situations – to losses, to deaths of people who were close to us. This process of medicalization must have some consequences. We stop thinking about things that were perceived earlier as something natural, something human. We start to think about things that were perceived earlier as something natural – as a disease. And it has to change our relationships and notions of our self, of people close to us – of love and death, even.

In your email to me, you mentioned a perfect example. The new example of workplace stress, of burnout, which the World Health Organization considers a syndrome. I think this is terrible in that it makes it seem like bad working conditions are somehow a personal problem; it’s a mental health problem, it’s not a problem of the workplace.

It’s part of this very much capitalist, individualist paradigm, which psychiatry is very much related to.

I think it just perfectly illustrates the medicalization of distress that results from poor social conditions. Bereavement would be another example, not of poor social conditions, but inevitable losses that people suffer during…

We’ll talk about deletion of bereavement exclusion from DSM-5. But first, let’s discuss this burnout syndrome. It is very interesting and is also related to the bereavement exclusion case. One can see this process as a part of medicalization; part of a capitalist, individualist point of view. This whole capitalist, individualist culture that uses medicine to internalize problems and hold the status quo in place, not to change politics, but to put everything onto humans. Yet we have a lot of people who suffer in their workplace, they cannot stage a revolution, they cannot change anything really – if they try to change something, they will get fired. So, the least we can do for them is something like diagnosing burnout. We can give them medicines and they will feel better. What do you think about that?

They’ll feel better and the workplace doesn’t change, so that would be a perfect way of trying to get people to adjust to social conditions that are not good for their mental health. By taking drugs or undergoing some kind of wellness programme in the workplace, they can feel better about a bad situation.

I read an article from the New York Times, it was published a few years ago. One psychiatrist who was interviewed was from some small town with a lot of social problems and many poor people living there. He said something like, okay, I am a guy who medicalizes, I am a guy who prescribes a lot of drugs to children from poor families, but I am in a position where I do the work that the social workers should do, and this is the only tool to help these children do better in life.

I don’t expect psychiatrists and other mental health professionals to be on the picket lines and creating the revolution. Their job is to look at things from an individual point of view. Individuals seek their help and that’s who they help; that’s their job. So I don’t have a problem with them. It’s a systemic problem, and what you were just saying raises a whole new aspect of medicalization, which is children. This is something genuinely new and, for the most part, a 21st-century phenomenon. It started happening towards the end of the 20th century, but the degree to which now – and here I am familiar with the American experience – children are being medicated is both astoundingly high and something that has no precedent.

We could look at this – like the doctor from the article – as a symptom of modern capitalism, of the competition that is very strong here. People are living in constant stress and these drugs are just used to make them work better in this area.

There is perhaps a correlation – it’s hard to say whether there’s causation, although there may well be – with the imposition on schools that are now being judged on the scores of their students on standardized tests. Disruptive students or inattentive students or students who don’t score well are not just harming themselves, they’re harming their teachers and their schools. It’s not only a reflection on themselves, so giving them stimulant drugs is a way of not just changing their own condition, but getting them to perform better to the benefit of the institutions, as well as the individuals.

It’s like from some dystopian movie or novel…

…it very well could be, but it also comes from reality. The emphasis is on testing in schools, which is quite new in the United States anyway, where it’s gone beyond just the individuals to the institution itself.

It sounds terrible to me.

Students have always hated tests, but now the teachers certainly don’t like it. They’re caught in this system that’s judging them and judging the schools by how well the students do on the standardized tests.

Do you think that if this process continues, that drugs will be increasingly used not to cure some diseases or problems or disorders, but as a tool to improve our action in life, to make us better among the competition, to make us work more effectively? That the social problems which are behind the architecture of social life will increase?

It’s not just schools that face this problem, it’s families as well. Especially with the change in family structures, both where you have far more women working, where you have many more single parent families, where it’s more difficult to maintain social control in the family. Medication then becomes one more tool that parents have to control children. It’s not only schools where this is a problem.

But do you see this as a replacement, as a substitute of something that should be in a completely different paradigm or field? Is psychiatry replacing politics, and is this some sort of a natural process? Or can it have bad consequences in the future?

It’s a meliorist tool to deal with disruptions. If somebody starts taking medication when they’re five, six, seven years old, that can’t be a good thing for that child, who’s not going to be a child for that long; who’s going to become an adult and perhaps going to get the brand new disorder of adult attention disorder.

Let’s return to bereavement exclusion, because the deletion of normal bereavement, normal grief from the DSM-V was very widely discussed. Of course, the psychiatrists said that it was because they couldn’t prescribe medicines for patients who had lost someone close and were suffering. But Jerome Wakefield said that this is just not true, that they could and it absolutely wasn’t a problem. How do you see this gesture?

The elimination of the bereavement exclusion was the best example I know of that indicates this breathtaking hypocrisy on the part of psychiatry. If you start with the general definition of mental disorder in the DSM, it uses bereavement as the exemplar of a condition that should not be considered a mental illness. It’s possible that something could go wrong and that it could become a dysfunction, but typically bereavement would be an example of how humans are designed to respond to loss. Bereavement is still in the general definition of mental disorder – they didn’t bother to take it out of that. Jerry Wakefield was the primary person saying: “But why only bereavement?” Bereavement, as it is in the general definition, is an example. It’s not the sole example, but it could stand in for workplace stress, for the kinds of depression people undergo when a relationship breaks up, when somebody loses a job. It’s natural to be sad, to be anxious about what’s going to happen to you in the future. This is the way humans are designed to respond to losses. Therefore, the bereavement exclusion shouldn’t be the sole exclusion – it should be the example of a loss event that stands in for many others. It should be expanded.

Jerry and his collaborators, occasionally including me, then looked at the major epidemiological studies. They’re not great, but they allow you in a very general way to look at not only bereavement, but other kinds of losses – losses of jobs, losses of relationships, and so on. You can compare people who have suffered those kinds of losses, become depressed and developed other conditions with people who became depressed with no precipitant. What this research shows is people who have suffered other losses are far more similar to bereaved people and to normal people – people without depression – if you look at them over time, than they are to people who have had no loss, but are depressed. The evidence was really quite clear about that. The extent to which psychiatry is claiming to be guided by empirical findings, would have meant expanding the exclusion. But they obviously went in the other direction and got rid of it, which truly made no sense. There was already existing in the exclusion an option that if somebody undergoing bereavement had just one especially severe symptom of depression, they could be diagnosed as depressed. So it was easy to diagnose someone who was suffering with what’s called in psychiatric terms ‘complicated bereavement’. It was already in there. They didn’t have to take it away.

So why did they?

Here I would say that Jerry Wakefield, Arthur Kleinman and others were arguing that bereavement stands in for a whole range of problems that don’t make people feel good. If you expand that to a whole range of socially-caused problems, that’s a pretty basic threat to the legitimacy of a large component of clients of psychiatrists. It poses a threat to the legitimacy of the profession. I think they understood that and said: “Hmmm…” And this is what I mean by breathtaking hypocrisy, given that their own definition of mental illness uses bereavement as an example, not as something isolated, but if you took the definition seriously, you would really question whether a large proportion of people who are getting treatment may not have mental disorders at all; they may be responding normally to bad social situations. Therefore, why are they going to psychiatrists?

It sounds very cynical.

In this particular case, I think cynicism is warranted.

At the same time, this is an announcement from a very important group of authorities – medical authorities, who decide what is pathological and what is not – that your reaction to such a natural thing as losing someone close is actually a disease.

It’s sort of an outrage to common sense.

It’s happening and it can hugely affect our culture, which is already lacking a space for this kind of experience.

That’s why I think bereavement was a stand-in for a much broader kind of phenomenon, which would be socially- and culturally-induced distress.

What do you think about the role, for example in this case, of the capitalist market machine? People who experience losses and bereavement and grief are not as productive as people who are happy. Maybe this is also a tool just to get workers better, and more quickly back to work again after these kinds of experiences?

On the one hand, bereaved people would represent a huge market. Everybody at some point in their life – 100% of individuals – will experience this. On the other hand, I haven’t seen any evidence that the drug companies have actually used bereavement as a way of marketing their products. What’s interesting about the whole bereavement exclusion – a major point of controversy around 2013 when DSM-5 came out – I’m amazed that it seems to have just dropped off the face of the Earth as a topic of discussion. I haven’t seen anything in the last few years.

What may happen with a culture in which such natural things are perceived as pathologies?

I don’t know if that’s happened yet. Certainly it happened in the DSM-5 process and among the group of psychiatrists who were developing the criteria. I think it’s so deeply-rooted, not just in culture but in nature. Grief is a natural phenomenon. It’s going to be tough to medicalize grief, in fact.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Introduction translated from the Polish by Julia Potocka-Ostaszewska