Yoga in Sanskrit means ‘what is appropriate’ and ‘what is systematically and constantly applied’. In this case, the point is what is appropriate to human nature. The conviction has become entrenched that everything related to yogis borders on some kind of mysticism. In fact, the yogis’ exercises and their observance of hygiene principles are based on their comprehensive knowledge of the human body, its anatomy, and the principles by which its organs function. For example, yogis flush the nasal cavity with warm, salty water. This prevents colds and certain infectious diseases, treats runny noses and most importantly, helps proper breathing.

The yogis’ physical exercises are an entire science of maintaining health and longevity – a science that was already formed thousands of years ago. The exercises don’t just include your muscles. The basic focus is on ‘training’ the internal organs, mainly the nervous system, on which your general health depends. The brain and spinal cord contain nerve nodes that direct the basic functions of the human body. Over the millennia, a series of classical exercises, known as asanas, have been developed in India; mastering them allows the activation of the more important nodes, and thus the exercise of control over the body’s physiological operations.

Exercise using the yogis’ system:

1. Tadasana – eastern pose

Raise your torso as high as you can, but don’t stand on your toes. Distribute the entire weight of your body evenly on both legs. Straighten your shoulders, pull in your belly a bit, knees straight but not locked. From the hips to the feet, the legs are touching, hands on the chest, diaphragm raised high. Think about nothing, keep absolute silence and concentrate your attention on your torso, especially the hips. Stand motionless for two to three minutes, avoid any wobbling. Do this exercise every morning until you achieve complete control over your muscles. Later, once or twice a week.

2. Eka Padasana – one-foot pose

Stand as in asana 1. No part of your body can be tensed up. Next, using your left hand, place your left foot on the inside of your right thigh. Keep your balance, standing on one leg. Concentrate on your relaxed left leg, whose whole weight is pressing on part of the right hip. The purpose of the exercise: to develop stability through conscious control over the movements of your muscles.

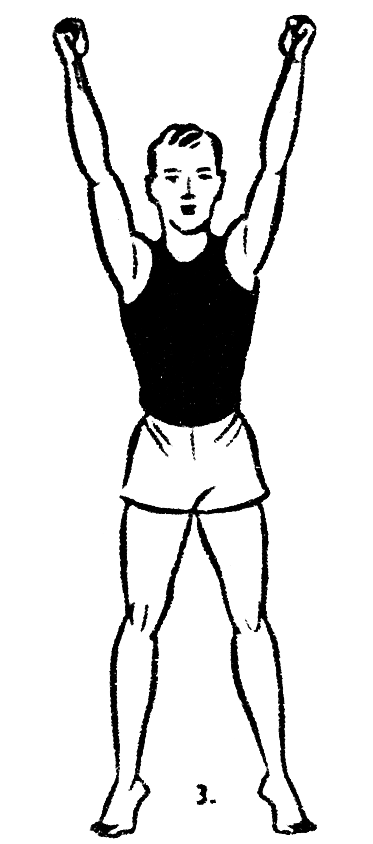

3. Talasana – stretching in the standing pose

Spread your legs to shoulder width. Slowly clench your fists and fold your elbows, standing up on your toes. In a fluid motion, throw your straightened arms forward, then upward, stretch out, allowing your ribs to fall. Stay up, concentrating on completely dropping your ribs, then stand flat on your feet, lowering and relaxing your arms. Take a deep breath.

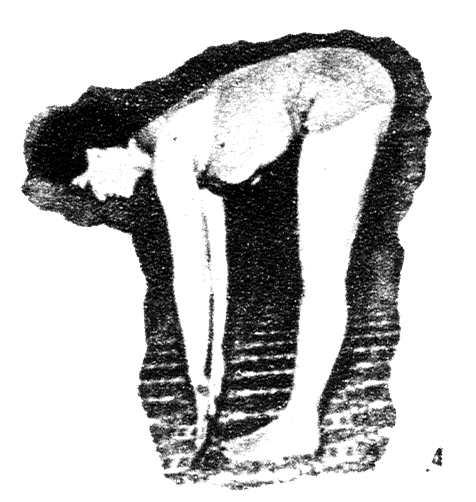

4. Padahastasana – hand to foot pose

Stand up straight, legs together, arms down. Slowly exhaling, bend forward (back straight, knees straightened). Pull in your belly, head forward. In this position, hold your breath for a moment. Returning to the initial position, breathe in.

5. Gomukhasana – cow-face pose

Sit up straight, on your heels (this can also be done standing), eyes closed. Put your arms behind your back, as in the illustration. Bringing your hands together, draw them to your body. If they don’t touch, use a towel to help, bringing the bottom hand up the towel. The purpose of the exercise: strengthening the muscles around your spine and mobilizing your arm joints. Also effective against hunching over.

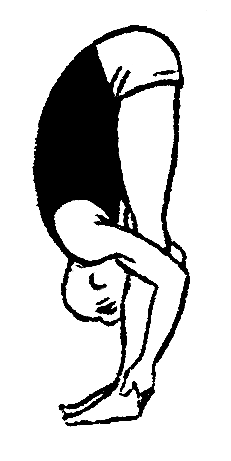

6. Hastapadasana – standing forward bend

Don’t bend your knees! When bending down, breathe out, to avoid squeezing your internal organs. Hang your head straight down. Hold the position for several seconds. Loosen the top part of your torso as much as possible. Returning to the starting position, breathe in. This exercise also affects the working of the intestines. Figure 6a presents the final stage of the exercise.

7. Utkatasana – chair pose

Legs hip width apart, hands on your hips or in front of you. Stand up on tiptoe and, keeping your heels apart, sit down, bringing your knees together. Hold the final stage, to feel the exercise. Start by doing one or two at a time.

8. Dwapada – double pigeon pose

Lying on your back, bend your legs at the knee, bring them to your chest and put your arms around them. Don’t lift your head, keep your spine straight near your head, bring your heels to your pelvis.

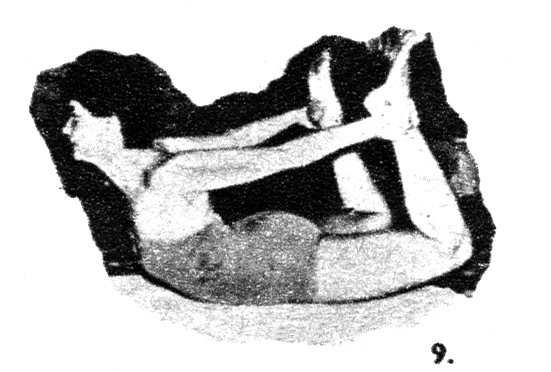

9. Dhanur Vakrasana – bent pose

This exercise consists of raising your head and pulling your knees off the floor, with straight elbows. Pay attention to relaxing all your muscles, except those around your spine and wrists. Repeat two or three times.

10. Ustrasana – camel pose

Kneel and lean back till your hands are resting on your heels. Next, increase the bend in your spine by pushing your belly and chest forward. In this exercise you should feel pressure on all your vertebrae, from the hips to the neck. The exercise helps your blood circulation, strengthens the lumbar and spine muscles and stimulates the endocrine glands. Don’t do this exercise in the evening!

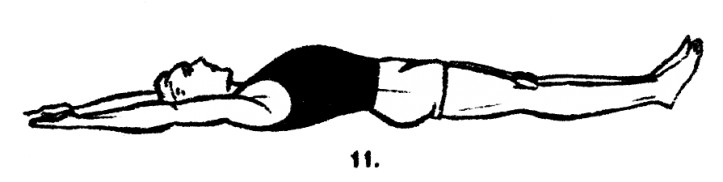

11. Yastikasana – stick pose

While stretching, take in air and don’t breathe out for 4-6 seconds. Repeat 2-3 times. This exercise encourages relaxation of muscles that are in constant tension because of improper posture. It also strengthens the usually weakened abdominal and lumbar muscles.

12. Bhujangasana – cobra pose

Lie on your belly, arms alongside your torso, hands on the floor, head resting on the floor. Slowly lift your head and neck back. Next, support yourself on your arms (as in the illustration) and, using your inhalation, lift your chest and upper abdomen. Don’t pull your hips off the floor; this is only for the upper part of your body, down to the waist. Avoid sudden movements.

13. Halasana – reverse cobra pose

Rest before doing this exercise. Next, lie on your back, arms alongside your body. Raise your legs, forming a right angle with your torso; then, breathing out, let them fall behind your head, without bending your knees. For maximum stretching of the back muscles, your legs should move as far as possible, toes reaching the floor. If you hold this position for a moment, you’ll breathe evenly and calmly. Start by doing it once, on an empty stomach. Initially, do it ‘in instalments’. This exercise supports the general strengthening of the nervous system.

14. Paryankasana – internal organ massage

Do this exercise in stages. Kneel, sit on your heels, keeping your lower legs on the floor. Lean back, resting first your hands, then your elbows, on the floor. Only then can you move to the last stage of the exercise (see Figure 14). Keep your knees together, because separating them reduces the tension on the internal organs. Don’t hold your breath. Exit the pose by lying on your side and rolling onto your belly. This exercise is especially significant for the organs in the abdominal cavity and pelvis!

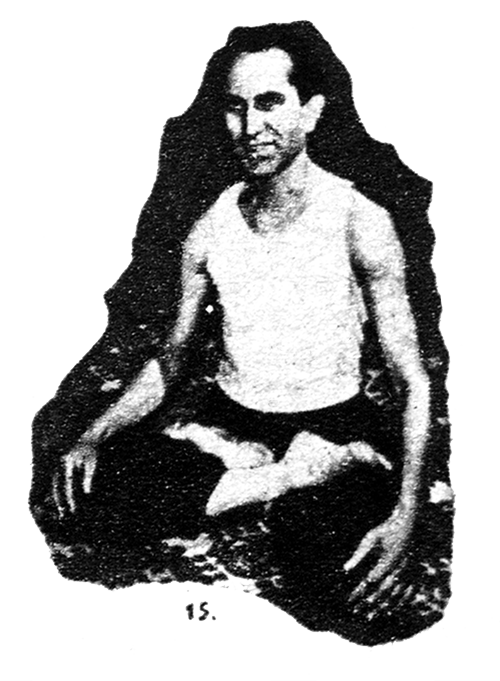

15. Padmasana – lotus pose

The lotus pose is essential both for doing the yogis’ full breathing and for achieving flexibility in the muscles of the lumbar and the lower limbs. This exercise is difficult, so it has to be done in stages. Don’t be rough with your muscles and joints.

Breathing

The most important element of these exercises is proper breathing – which is essential for bringing oxygen into the blood – and circulation, the work of the heart. The yogis aren’t just interested in full, deep inhaling and exhaling, making the entire ribcage work. Breathing, they say, should be slow and fluid. The muscles that take part in the breathing process should engage gradually. For this purpose they have to be ‘trained’.

The yogis distinguish between regular and prana breathing. Prana, as they understand it, is neither air nor oxygen, but a substance found in air, water and even food. This ‘prana energy’ can be positive or negative. It has the property of collecting in the basic nervous centres of our brains, and influencing the working of the entire central nervous system. The yogis have developed a special breathing exercise that helps replenish the reserves of ‘prana energy’ in the system.

But enough about the yogis’ prana. Even without it, the problem of breathing deserves special attention, because, in fact, we don’t know how to breathe. Our shallow, often arrhythmic breathing, so typical of most residents of contemporary cities, fills barely one-tenth of our lungs’ capacity.

The yogis stress that humans must consciously regulate the process of our breathing, and they say at the same time that breathing through your mouth is something as unnatural as eating through your nose.

Asana (or, position)

Admittedly, the Hindu asana is externally similar to our gymnastic exercises, but they’re not the same thing. The fundamental difference is that an asana isn’t a quick repetition of defined movements (throw out your arms, your legs; turn your body; bend; etc.) but a pose, a strictly defined position, in which the body is held for a certain time. The classical Indian exercises are performed while maintaining a strictly defined rhythm of breathing. Each classical exercise has a concrete goal: to force a certain group of muscles, nerve node or part of the nervous system to work. The exercises are performed in conditions of absolute concentration on the organ in question. They must be performed every day, but not after eating. Some exercises can’t be done before sleep, because as a result of applying the yogis’ full breathing, the body will be so enlivened that it’s hard to force it to sleep.

At the moment, the yogis’ system of physical education is not only taught in Indian schools and military academies, but also promoted among the masses by the Indian government. The yogis’ system is also practised ‘in private’ by many well-known personalities (Prime Minister Nehru!). And not only in India: these exercises are used by the great violinist Yehudi Menuhin and the outstanding Polish pianist Witold Małcużyński.

(Illustrations from the Soviet weekly “Knowledge is Power”)

Translated by Nathaniel Espino