The author’s position on how it’s better to walk than to sit, which is, at the least, uncomfortable. And not only because she’s stuck at a desk on a hard chair.

Her feet sink into the sand. Sylwia Nikko Biernacka, with a 22-kilo backpack (inside is the cheapest – but also the heaviest – tent that was in the shop) has set out on the road. She has 440 kilometres to cover along the coast of the Baltic, from Świnoujście to Piaski. She walks tens of kilometres a day. Alone. Sometimes barefoot, sometimes in shoes.

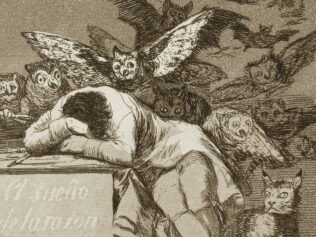

She walks to figure out what she’s about. “I had the feeling that I was longing for something, but I wasn’t quite sure what it was, and I didn’t have time to think about it,” Biernacka recalls. Friedrich Nietzsche, a fan of walks in the mountains of the Black Forest, would certainly approve. “Remain seated as little as possible, put no trust in any thought that is not born in the open, to the accompaniment of free bodily motion—nor in one in which even the muscles do not celebrate a feast,” he wrote in Ecce Homo. “All prejudices take their origin in the intestines. A sedentary life, as I have already said elsewhere, is the real sin against the Holy Spirit.”

Walking changes your body and your mind, and sometimes your social life too. Writing a text about walking is a thankless task: I have to keep the readers in their seats, to encourage them to get moving as fast as possible. At least I’ll try to be quick.

“I need a daily dose of movement; a stretch that I walk,” Biernacka says. “Then I have time to think. But I also feel that my body demands it.” Walking stimulates the circulation and gets oxygen to the tissues. It increases the capacity of the hippocampus, the part of the mind responsible for memory. New connections are set up between neurons, which increases our cognitive capabilities. Marily Oppezzo and Daniel Schwarz, psychologists from Stanford University, observed how two groups of students dealt with tasks requiring creativity: the first group could walk around freely, while the others were told to sit. The first group was definitely better. And research by Marc Berman of the University of North Carolina has proved that when walking, we remember better. (But it seems that this knowledge is intuitive – haven’t you found yourself wandering around the room while pounding new vocabulary into your head?)

How much do you have to walk to stay in shape? The doctors Anders Hansen and Carl Johan Sundberg, authors of the book Hälsa på recept [Health on Prescription], aren’t demanding; they say that to stay healthy, half an hour of quick walking every day is enough. To mitigate the symptoms of depression, it’s enough to walk or run two or three times a week, for 30 to 45 minutes each time (maintaining this level of activity for at least two months). Hansen and Sundberg say that with moderate depression, regular movement can work similarly to drugs.

The writer Henry David Thoreau, an advocate of wildness and the author of “Walking” demanded more of himself. He wrote in it, unapologetically: “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.” Thoreau complained that sitting in his room, he became overgrown with rust, and marvelled at other people: “I confess that I am astonished at the power of endurance, to say nothing of the moral insensibility, of my neighbours who confine themselves to shops and offices the whole day for weeks and months, aye, and years almost together. I know not what manner of stuff they are of—sitting there now at three o’clock in the afternoon, as if it were three o’clock in the morning.”

Walking is no sport

It’s increasingly rare that we walk further than to wherever we parked our car. Meanwhile, for thousands of years, walking was a basic form of movement: it ordered the thoughts and awakened the imagination (perhaps Aristotle and his students did philosophy during walks); it allowed you to contemplate nature, healed the body (literally and a little less directly, as is shown by the votive offerings in pilgrimage sites).

“Walking, by virtue of having the earth’s support, feeling its gravity, resting on it with every step, is very like a continuous breathing in of energy,” Frédéric Gros, a professor of philosophy at Paris XII, one of the top French universities, writes in A Philosophy of Walking. And he adds: “Walking is not a sport. Sport is a matter of techniques and rules, scores and competition, necessitating lengthy training: knowing the postures, learning the right movements,” from which it clearly follows that Professor Gros knows nothing about the successes of Polish Olympic walker Robert Korzeniowski, though he appreciates attempts to breathe the sporting spirit into walking: high-tech shoes, fashionable sticks, socks that breathe.

Gros believes there are three basic types of walking: contemplative (which cleanses the mind); cynical (not because of the intentions of the person moving their feet, but to stress the roots of this type of wandering, which derives from the ancient school of the cynics, who eagerly provoked others and broke conventions, all the time wandering around like dogs, from which their name derives); and one that brings together both of these types of contemporary urban wandering. The flaneur who engages in it “moves slowly, but his eyes dart about and his mind is gripped by a thousand things at once,” as Gros writes. “He has better things to do: remythologize the city, invent new divinities, explore the poetic surface of the urban spectacle.”

Big cities, especially in America and East Asia, aren’t walking-friendly; often they have no sidewalks. Meanwhile, as the Danish architect and urban planner Jan Gehl has been saying for years, the city is supposed to be for people – meaning for walkers, not cars.

Only the blue sky matters

Where you walk is not without meaning. A stroll in the city stimulates and activates, and a wander through the woods boosts your memory. Perhaps that’s because to avoid getting lost, you have to create a map of your surroundings in your head. In gardens, parks or woods, it’s easier to concentrate. We learn faster, even when we see greenery only through the window (it’s worth walking around your desk to increase the capacity of your hippocampus).

“I read once that we project our souls onto the landscape,” Biernacka says with a laugh. “My soul feels great by the sea, where there’s nothing and also everything: space, the line of the horizon, a different colour of the water every day, sand, forest. In these seaside rambles, I like it that I’m at the intersection of different elements: I have contact with the earth, the water and the air, and sometimes with fire too when I’m at a bonfire along the way.” As Gros writes: “When you are walking, there is only one sort of performance that counts: the brilliance of the sky, the splendour of the landscape.”

Good mood

For Nietzsche, long walks were medicine for his terrible headaches and eye pain (“I walk on average an hour in the morning, three hours in the afternoon, at a good pace – always the same route: it is beautiful enough to bear repetition,” he wrote in March 1888). They allowed him to write, but also to escape from an excess of stimuli. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another great philosopher and writer, used to say that when his body stood still, his thoughts did too. “I never do anything but when walking, the countryside is my study. The mere thought of a table, paper and books bores me, all these work tools discourage me; when I sit to write nothing comes to my mind and the necessity to be witty intimidates me,” he wrote in Mon portrait. Immanuel Kant maintained his spiritual and bodily health with a walk every day after lunch (supposedly he left his regular route only twice: once to buy Rousseau’s Emile, and once to inquire about the outbreak of the French Revolution).

Gros believes walkers experience pleasure, joy, calm and happiness. But walking also frees you from the less pleasant emotions. The Inuits, for example, believe in the cleansing power of walking. When they get angry, they take a stick and start walking until it passes. Then they jam the stick into the snow. They get rid of their anger, and looking at the hole in the snow, they know how deep their rage was.

“Lots of things come out of you through your feet,” Biernacka says. There have been times she’s walked while crying, or angry and swearing out loud. Sometimes when she’s walking alone, she sings.

Don’t over-exhaust the warmth of your buttocks

“First I had the idea to follow the trail of the lighthouses,” Biernacka says. During that journey, the dream of walking the whole coast was born. She didn’t manage to fulfil it for a long time. In 2012, Biernacka switched to freelancing. Nothing in particular was happening, but she experienced frustration. “I wanted to photograph, but I didn’t have time. I was running a one-person foundation, but I didn’t get financing. I was frustrated that I had cool ideas that weren’t being realized. I was also a newly qualified trainer; I was starting to do workshops and trainings.” In the end, she woke up one June morning and felt that she had to walk.

She organized an auction of her photos, raising 2000 złotys (around £400). She bought a tent, borrowed a backpack from her sister, looked at the map. She got frightened that long stretches of the coast are wilderness, which she’d have to conquer alone. A friend gave her a quick course in self-defence. On 1st August she packed up and set out. She decided she wanted to use this journey to support a woman who had had both legs amputated – to fund prosthetics for her. Biernacka believed that her march would encourage some prosthetics firm to help. It worked. Thus far, her annual walks, known as the ‘440 km project’, have delivered support for three disabled women (prosthetics, two wheelchairs, a lift, psychological help), and the beach in Jastarnia has been made accessible for those who don’t necessarily have two healthy legs.

Asked by a Guardian journalist whether it’s better to write about walking or take a walk, Gros replied without hesitation: the latter, of course! So I’m abandoning my chair and desk. I don’t want to wear out the patience of my buttocks.

Why you should walk barefoot

“Free your feet, and you mind will follow”. That’s the motto of the Society for Barefoot Living. There are some quite well-crafted arguments for taking off your shoes. Walking barefoot:

– prevents problems with the circulatory system (when we go barefoot, our leg muscles are more effective in pumping blood to the heart);

– relaxes you (even the most passionate fans of soles, heels and laces);

– is a great massage (your feet contain 72,000 nerve endings);

– prevents discopathy and foot deformation;

– hardens your body and allows you to avoid colds (especially when we walk on grass or wet stones, or wade in cold water). Useful during vacations on the Baltic.

Translated from the Polish by Nathaniel Espino