Over 60 years ago in the Soviet Union, a group of young hikers never returned from the mountains. The prosecutor’s office and the communist party opened an investigation, but the case soon fell into oblivion. Stasia Budzisz talks with Alice Lugen, an investigative journalist and the author of the book Tragedia na Przełęczy Diatłowa [The Dyatlov Pass Tragedy], about what really happened at Otorten Mountain.

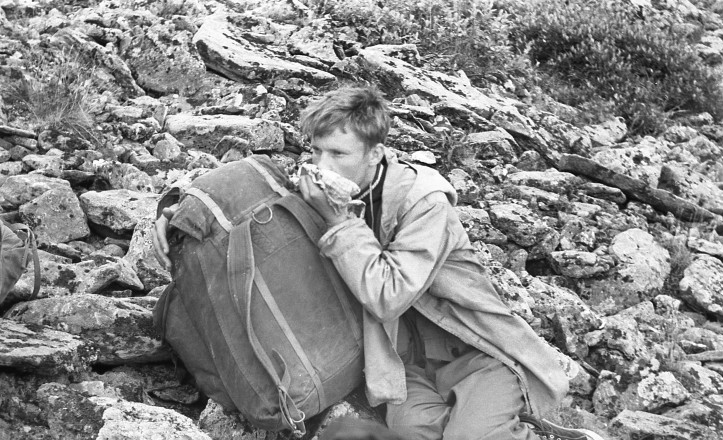

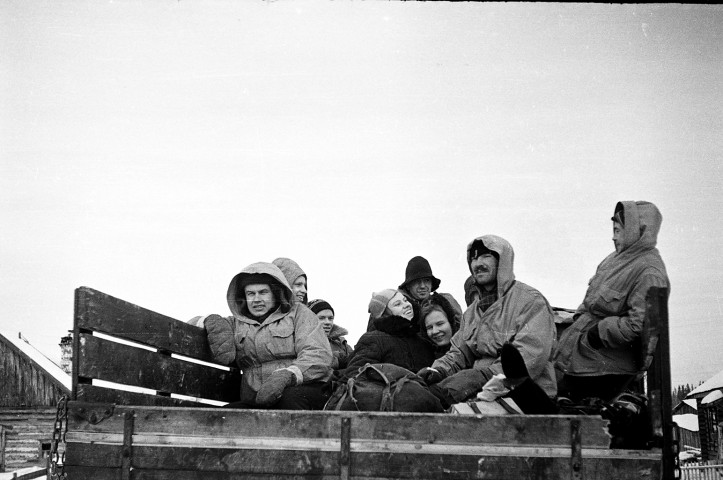

In the winter of 1959, a group of students and graduates of the Ural Polytechnic set out on an expedition to the mountains. They wanted to reach the peak of Otorten in the northern Urals, to celebrate the 21st Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The journey was led by Igor Dyatlov – an ambitious final-year student of radio engineering and an experienced mountaineer with remarkable orientation in the field. He was considered someone who always kept things under control. Nobody came back. All the hikers died in uncertain circumstances, which still haven’t been explained. The investigation concluded that their death was caused by a “compelling natural force”.

Stasia Budzisz: How did you come across this case?

Alice Lugen: I learned about it in Russian media, which I regularly follow, and right from the start I approached it with great caution. The disclosed information seemed unbelievable and almost absurd. What I found most surprising was that the investigation was supervised by Leonid Urakov – the deputy prosecutor general of the Soviet Union. In the publications on the incident one could see the names of high-profile politicians like Nikita Khrushchev, Boris Yeltsin, Andrei Kirilenko (named as a possible successor to Leonid Brezhnev) and Nikolai Stakhanov, the Minister of Internal Affairs. This is why initially it seemed to me unlikely that the quotes provided by Russian journalists were sourced from the case files.

What did those quotes consist of?

They included, for instance, some speculations about shaman’s prohibitions, the Mansi people’s sacred mountain, and local legends. In his testimony, one of the victims’ fathers talked about a missile changing its trajectory. Soldiers and other witnesses mentioned military tests and objects moving across the Ural sky. It all seemed implausible, which is why I decided to verify it myself. It turned out, however, that those quotes were indeed in the files. The more I was digging into this case, the more questions and doubts I had. Now it’s been seven years since I got involved.

Let’s start from the beginning then: who were the victims?

They were students and graduates of the very prestigious Ural Polytechnic Institute in Sverdlovsk, known today as the Ural State Technical University in Yekaterinburg. The team was led by Igor Dyatlov, and among its members were Zina Kolmogorova and Yuri Doroshenko, who had been romantically involved but split up shortly before the journey. The team also included two other students: Aleksander Kolevatov, who worked at Moscow’s secret Institute 3394 (aka ‘the brains behind the Cold War’) and Lyudmila Dubinina. There were also three graduates: Rustem Slobodin, Nikolay Thibeaux-Brignolle and Yuri Krivonischenko. The last two worked in the Mayak nuclear facilities, and Krivonischenko was in addition a liquidator of the famous Kyshtym disaster. Thibeaux-Brignolle, on the other hand, was a descendant of French aristocrats who lived in Russia. He was born in the labour camp that his father was sent to.

You’ve mentioned eight people, but there were nine victims…

Yes, there was also the oldest member of the group: Semyon Zolotaryov, born in 1921. His biography, however, is more complicated and gives researchers a headache. A war veteran who worked in many tourist facilities, he introduced himself using the fake name Alexander. Nobody had a clue why he insisted on joining Dyatlov’s team. He was neither a student nor a graduate of the Polytechnic Institute. Nobody knew him and historians were doubtful about his war experiences. He was suspected of working on behalf of a foreign intelligence agency. The informants of some investigative journalists shared unbelievable stories about him. His relatives requested his body to be exhumed since the description of the deceased in the autopsy report didn’t match Semyon. After the exhumation in 2018, two DNA tests were run. One confirmed his kinship with the Zolotaryov family, the other did not.

We like clear explanations; we want to know what happened and who was to blame. When you began working on the book, you were aware that you wouldn’t be able to answer these questions. What is it like to work on something known to be inexplicable?

There are people who have been researching this tragedy for 60 years. They have compiled a long list of questions that still remain unanswered. As a reporter writing in Poland about the Dyatlov Pass tragedy, I have decided that my task is twofold. First, I need to point out what hasn’t been explained and why. Second, I need to report what was proved beyond doubt, providing sources. My goal wasn’t to crack this case – this simply isn’t possible today.

Many theories explaining what happened and who was guilty have been put forward. One of them was that the hikers were attacked by escaped prisoners from the Ural labour camps; another, which was seriously considered, states that they were brutally murdered by the local Mansi people. Needless to say, the latter was the most convenient one for the government.

That’s right. This theory was the most plausible one for the party, especially since it wasn’t fond of the Mansi people. The rebellious people of the Urals were hard to subdue. They governed themselves and chose their shaman, a leader of their community, in democratic elections. They weren’t interested in Soviet politics or the ideas expressed by the party. Moreover, the lands they inhabited were rich in natural resources. Let’s not forget that this was also where the Ural Military District was located. If they had managed to move the Mansi slightly more to the north, a lot of territorial conflicts would have been solved. The ritual murder theory was proposed by the party’s First Secretary from the city of Ivdel, but it met with resistance from the prosecution. The Mansi were not present at the site of the incident. They didn’t see the hikers on their way to the mountain, only the traces left by their skis. They had no interest in killing them since their settlements were often visited by Russian tourists, who in exchange for food and a place to stay would give them products rarely available in the taiga: nails, salt, sugar and medicine.

Another theory, the most sensationalist one, involved an American spy.

This one is like an insult to both CIA and Soviet counter-intelligence, but let’s follow it step by step. According to this theory, US spies, who in 1959 were wandering around the Ural Military District (which in itself seems totally absurd), contacted one of the group members: Yuri Krivonischenko. He worked in the Mayak nuclear facilities and lived in the so-called closed city that couldn’t be entered without special authorization. It is true that he would have been a very important asset since he possessed information about the 1957 Kyshtym disaster – one of the worst nuclear accidents in history, which influenced the course of the Cold War. Krivonischenko was believed to have been recruited by operational intelligence officers. However, they didn’t want from him any descriptions of the technology developed at Mayak, the names of those who had used this technology, or any documentation on the disaster. Rather, they were only interested in the irradiated trousers and a sweater.

This story was described in Alexey Rakitin’s famous novel. He suggested that three victims of the Dyatlov Pass incident were working for the KGB, and Krivonischenko was, in addition, a CIA informant. This wouldn’t be a problem if the book were a crime fiction; it is a real page-turner. But the protagonists are real-life people whose relatives are still alive.

Still, this is literary fiction that abides by its own rules.

Yes, but the book was supposed to shed new light on the tragedy. As a result, readers were unable to tell fact from fiction. For example, the author suggested that Lyudmila Dubinina’s tongue was cut off. This isn’t true. Her body, found in snowmelt, had already undergone the process of decay and advanced decomposition, just like the bodies of other victims found on the same day. In the autopsy reports, considerable soft tissue damage was described in detail. Nobody cut off Lyudmila’s tongue or plucked out the eyes of the deceased.

Some things cannot be avoided once a tragedy becomes part of pop culture. Similar tendencies are observable in the case of Chernobyl.

Different perspectives clash here. Of course the author has the right to freedom of expression and can write a book inspired by the events at the Dyatlov Pass. Nobody can stop him and nobody should try. At the same time, however, the victims’ families have the right not to be tormented. It is hard to come up with any solution and I’m not in a position to offer one.

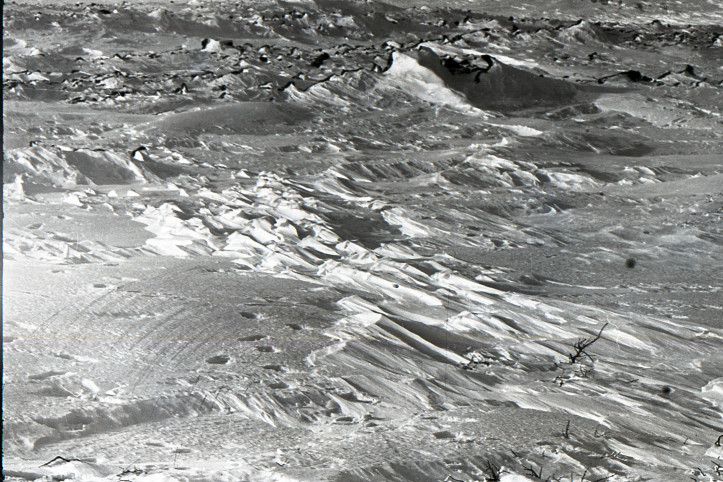

Some explanations also involved an avalanche and wolves…

The victims’ families know the context of the 1959 investigation. They heard about a serious, three-month-long fight between prosecutors and party leaders. They are aware that the investigation was closed at the party’s request. Why was the case report written by the Minister of Internal Affairs? Why did the deputy general prosecutor of the USSR supervise the investigation? Why in 1959 were the victims’ parents told to stay quiet and ask no questions? Why were the files sent to Moscow without a reference number and kept classified? Why wasn’t the prosecutor allowed to see the site of the tragedy after the snow melted, and why did witnesses pledge to remain silent? Why was Rustem Slobodin’s father told that his party card would be taken away if he kept digging into the case? Neither an avalanche nor wolves answer these questions.

This brings us closer to the very broad term gostajna, which stands for ‘state secret’. It is striking that between 1959 and 1960 in the mountains across the Soviet Union, around 150 tourists died. Given the size of the country, this doesn’t seem a lot, but, importantly, only this one case was classified as highly confidential: ‘burn after reading’.

It should be remembered, however, that tourism was very popular back then across the Soviet Union and thousands of young people set out on such treks. No official statistics on minor accidents, like injuries, were kept. Only the number of fatalities was recorded. Yet no other incidents of this sort were dealt with by the most important people in the country. No other files were classified and no other case was supervised by local party officials. The Dyatlov Pass tragedy was an exception: the deputy general prosecutor of the USSR would travel from Moscow to Sverdlovsk only to supervise Ivanov’s investigation.

But the 1959 investigation was closed by the local authorities, not the general prosecutor. Why?

On 28th May 1959, Ivanov closed the investigation, announcing “compelling natural force” as the cause of the tragedy. The document was also signed by Stepan Lukin, the head of the investigative department in the prosecutor’s office for the Sverdlovsk region. Today it is known that they were forced to do it by Afanasy Yeshtokin, the Second Secretary of the party in Sverdlovsk, and Andrei Kirilenko, the deputy of the First Secretary. In March 1959, Kirilenko exchanged telegrams on the Dyatlov Pass tragedy with Nikita Khrushchev himself. We know about it from the prosecutors.

In the 1990s, Lev Ivanov apologized to the families of the victims. After reading your book, I’m under the impression that for the rest of his life he was completely unable to deal with what happened.

It was eating him till his last days. Since the 1970s he had been writing journals in which he was reminiscing about this investigation. When in the 1990s a journalist asked him why the case was closed, he gave a very honest answer: “It had exhausted me completely.” Ivanov was the only one who offered an apology. He was also the first to describe what was really happening behind the scenes. His article stupefied journalists – nobody had a clue that it looked like this.

You write a lot about negligence on the part of the hikers and their supervisors from the tourist club. For instance, you mention that the expedition was considered an ‘official business trip’ so that it could be subsidized. Was anybody held responsible for that?

The report closing the case included a list of people who failed to take care of the formalities. All of them were part of the sports club, the tourist club at the Ural Polytechnic, and the tourist route commission. When the hikers disappeared, nobody knew where to search for them.

You point out that while Dyatlov’s group was equipped with experience, compasses and intuition, they didn’t have what we would consider today a necessity: a map.

The hikers from the Ural Polytechnic Institute knew that the maps of the northern Urals were kept confidential because the Military District was located there. But Lev Gordo, the head of the sports club, was clueless. It wasn’t until the group disappeared that he realized that the sky over the northern Urals is a prohibited military airspace and that a civilian rescue team couldn’t be transported there from the Ivdel military airport without the prior consent of the Ministry of Defence. And the maps were so diligently protected that even Ivanov couldn’t see them.

What is, in your view, the most plausible theory of what happened at the Dyatlov Pass on 1st February 1959?

There still isn’t enough evidence to give a definite answer. The prosecutors who ran the 1959 investigation agreed that it was a military accident, and many people are inclined to believe this – the majority of investigative journalists, families and friends of the victims, rescuers, as well as prosecutors working today. Most researchers and Yuri Yudin (the only survivor, who left the expedition earlier due to sciatic neuralgia) also arrived at the same conclusion. This theory, just like others, has its strengths and limitations. We need to remember that this is still all guesswork.

Once you have dug deep into this case, is it possible to distance yourself from it?

I admit that I’m committed. Not only me: I talked with the prosecutor who told me he couldn’t give up this case because he saw the 1963 picture of Yuri Yudin climbing Otorten Mountain. This huge man confessed he was crying like a child over this photo and couldn’t stop. Many researchers and journalists have been working on the case because of their emotional involvement – some of them, like Petr Bartolomey and Sergey Sogrin, since 1959. They were both friends of the victims and members of the rescue group.

You also write about disorganized documentation and the inability to find sources. Didn’t you want to give it all up?

No, but some journalists did have enough and have given up. When I first read the case files, I had 100 questions. After reading them 50 times, I had 1000 questions. Chaos is not the only problem. The files are full of inconsistencies and inexplicable mysteries. There is, for instance, a typescript titled “A copy of Kolmogorova’s journal”. It differs radically from the manuscript written in pencil, which the prosecution gave to her family. The question is who in fact wrote it? Why does it cover events that didn’t take place during the Otorten expedition?

There are numerous examples of this sort. One can find two different versions of the closing investigation report and witness questioning dated 6th February – 21 days before the prosecution opened the investigation. The location of ‘livor mortis’ on the bodies of the four victims doesn’t correspond to the positions in which their bodies were found. The files fail to indicate which prosecutor was in charge of the investigation over which period. It also remains unknown when the case was moved from Ivdel to Sverdlovsk, or where the documentation prepared by Vladimir Korotayev, the first prosecutor to lead the investigation, is. The second volume of the case files consists of classified correspondence, marked as ‘burn after reading’. Almost every sentence there raises countless questions.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Read an excerpt from “The Dyatlov Pass Tragedy”.