I’ve returned to Pokrzydowo, to the Babalski family’s organic farm. This time I want to talk with Farmer Mieczysław about the autumn. Fortunately, it won’t be just a conversation.

Right at the start of our meeting, Mieczysław encourages me to taste the wormwood from under the fence. I try it. It’s bitter as death, but supposedly good for your stomach.

“Aaaaah, it’s bitter!” I yell, spitting the chewed-up leaves onto the ground. “How can you stand to eat that? Is it going to poison me?”

“Nah, it won’t poison you,” he says with a smile. “I mean, that’s what you make absinthe from. Oh, and here’s ground elder, try it. A little more delicate, right?”

It’s true, this is a plant I could substitute for rucola in a salad with a vinaigrette. It turns out that it’s good for gout. I prefer not to know what that is, so I tear off more of the small leaves and stuff them in my mouth.

“When does the autumn begin in farming?” I ask, sitting on the back of the scooter.

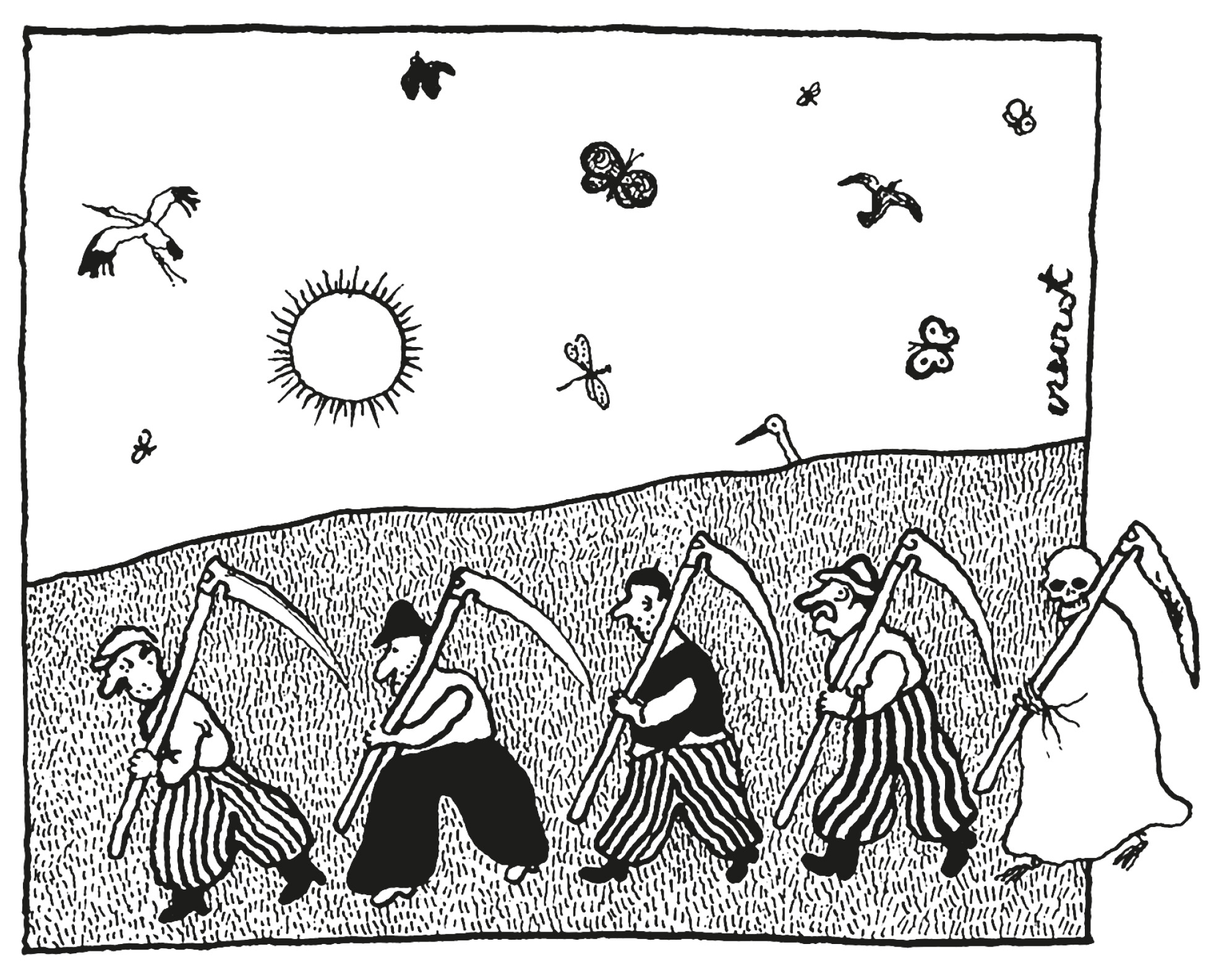

“When the grains come off the field and we do the post-harvest crops,” says Mieczysław, pulling on his helmet and starting the engine. We head to the orchard. “We’re preparing the soil for next year. Already in August we do ‘skimming’, a shallow ploughing. Then the harrow levels the soil. And the cultivator goes out only in the second half of September. The soil life has already yielded its crops, and in the autumn it slowly goes to sleep. But that’s precisely when the weeds become active, gathering energy for the coming year. Couch grass, field thistle. The cultivator pulls out their stolons, meaning their roots. Then the sun dries them out. That’s also the time when the fruits and the root vegetables are gathered, to have food for the winter.

“And will you sow anything else?”

“Yes, in the field, where we sowed buckwheat and phacelia. Phacelia is a good plant for honey, but also very important for the soil; it has long roots that bring calcium and phosphorous from deeper layers. We harvest the buckwheat at the end of August for groats and plough the rest under. And in the middle of October, we sow winter crops, spelt or emmer. You see how little fruit there is this year?” We ride between the trees and Mieczysław parks the scooter. “It’s all connected with the planets. Last year was the year of Venus. There was the most sun, because Venus is hot, like a woman. Things didn’t turn out too well for us in the fields, because it was too hot. But the orchard gave lots of fruit, and with good quality. And this year was the year of Mercury, which is usually infertile when it comes to fruits. The weather’s changeable, the plants were exhausted after the previous year. Next year will be the year of the sun, there will be more rain and humidity.”

“What do you do with the fruit?”

“Apple compote. I can the pears. But primarily we dry a lot. That’s the best preservation, and the best food for the winter. All the sour apples, like the russet, are sweet and good after drying.”

“And the plums?”

“Those too. The best are the common purple plums picked in September – after the first autumn frosts. That’s when the complex sugars convert into simple ones, and the fruits are sweeter. Carrots and beetroots are also harvested after the frost – they’re sweeter, which makes them keep better for the winter. But in the past few years there haven’t been frosts. They start only in November. And then it’s too late – the fruits and vegetables have been picked long ago, and they don’t have that sweetness.”

“Has anything else about the autumn changed?”

“It starts earlier, the leaves fall faster. And it lasts almost till the spring, because there’s no real winter. Before, the ground would freeze at the beginning of November, and thaw in March. Now it rarely freezes, just for two or three days and that’s it. The life of the soil has undergone a big change. Sometimes the ground is so dry that it’s hard to prepare the fields for the autumn sowing.”

“Can these changes in the weather have a significant effect on your crops?”

“We’ll see… I think everything can survive, it’ll be alright. That’s why the happiest person is somebody who has something to do for twelve hours a day. Because if you don’t, you have to have a whole lot of money to be able to spend it in that time. We used to say ‘work ennobles’, ‘ora et labora’. And now they go out in the fields and curse! The farmers, I’m sorry, have cursed farming!”

“There was a time when they didn’t?”

“If I had cursed in front of my granddad, I’d get a slap. I worked for ten years on collective farms, as an animal technician, and I was always sensitive to cursing. I had this one worker in the barn who would curse. I’d tell him: ‘That cursing has made all your cows sterile.’ Because cursing is chaos. And chaos is stress. When an animal lives in stress, there’s no fertility. When you curse, you create bad energy around yourself. Usually because something is hurting you, you’re suffering, you’re constantly afraid of something. And it’s the same in conventional farming – if you destroy and eliminate, you’ll live in stress, because you’re even afraid of these plants. And humans have to live together with nature, not against it. If you live in goodness and are surrounded by a good atmosphere, you don’t have to be afraid of anything. My workers know they can’t curse, because then the food they pack is cursed.”

“How do the animals behave in autumn?”

“They’re calmer, they put on weight – they’re preparing for the winter. That’s why it’s best to slaughter in the autumn. I’m a vegetarian, but my family eats meat. You have to use the roosters for broth. If you leave them, the chickens won’t eat from their perches. They’re afraid if there are too many roosters. We say ‘the rooster thought about Sunday, and on Saturday they cut off his head.’ The turkey, too.”

“And what’s the cows’ milk like in the autumn?”

“Sweeter. In the spring, when they eat sweet grass, it’s more watery. But from the autumn they get hay and vegetables, mostly potatoes and beetroot, which contain a lot of sugar.”

“What is autumn for you?”

“The fogs come, the fields become black. At the turn of September and October, the Indian summer is still in full swing, but there’s less and less sunlight, less and less energy. The joy of life is in the springtime. And in the autumn you’re more lethargic, because you’re tired from the summer. It’s a time of calm and relaxation.”

“Relaxation? But you have so much to do!”

“Take it easy, these things happen. In the morning you can sleep in, until 6.30. And you go to sleep earlier; I’m usually in bed by 9pm. Because one hour of sleep before midnight is like two hours after.”

“When you wake up, don’t you think ‘Oh no, today I still have to do that cultivating’?”

“For me, work is a joy! I can’t wait to get up in the morning, go out and get to work! If I did it by force, things would grow by force. Because you have to love the earth, then it will be grateful to you. There’s an old saying, ‘Earth is like a mother’. If you respect her and care for her, she’ll give birth. And if you torment her, she’ll start to decay. And that’s why there’s an increasing problem with conventional agriculture. The use of modern fertilizers makes the soil into steppe, it becomes dead.”

“So what comes next?”

“They say, ‘If you knew the world was going to end tomorrow, what would you do today?’ I think I’d work. And maybe it won’t end? Organic farming means we can return to normal.”

“And do you burn the leaves in the orchard?”

“I don’t do anything with them. People used to burn leaves to clear the fields. You burn them and you immediately have order. But a lot of energy escapes. Because the leaves contain food components for the life of the soil. When they rot, they’re nourishment for the earthworms for the whole year. They break down and form humus, meaning life. And if you burn them, all you’re left with is dead ashes.”

Translated from the Polish by Nathaniel Espino