“The whole purpose of childhood is to allow us to have a new generation that is going to see things and understand things in a different way.” Alison Gopnik, psychologist and philosopher, urges mothers and fathers, grandmas and grandpas, aunts and uncles to take risks. Let children experiment (even if they want to become carpenters, not doctors). I love people who turn stereotypes, common sense ideas or so-called evident truths upside down. Providing, of course, that they do it with concern for scientific and philosophical credibility. One of those people is Alison Gopnik, a psychologist and philosopher at the University of California, Berkeley, one of the most distinguished modern researchers studying childhood. That’s why her books on babies’ minds (especially The Philosophical Baby) and, more recently, parenthood (The Gardener and the Carpenter) are so fascinating and refreshing.

Gopnik doesn’t beat around the bush. She says there is a pervasive, culturally-entrenched myth that parents have a great influence on their children; that they shape them like the potter’s experienced hands shape a piece of clay. This myth is not only false but also harmful. Parenthood isn’t about playing a god who creates another human being in his own image. Quite the opposite: for a child freedom is essential, Gopnik says, adding that another thing of great educational value is diversity. The more people around you the better. Nothing beats a huge, multi-generational family in which everyone, not just mum and dad, is responsible for raising a child. Especially if you add a pinch of anarchy, disorder and chaos. That’s the best possible environment – order and discipline cannot compare.

Well, judging by the dozen or so jackets and coats of different sizes piling up on a coat rack in her Berkeley home, Alison Gopnik practices what she preaches, which is a rare thing today. She welcomes me warmly at the door and offers tea. She then disappears into her kitchen, while I try to add my jacket to the layer cake that is the rack. Just when it seems I have succeeded, the overloaded rack falls down with a loud thud.

How embarrassing, I think as I rush to collect all the jackets and coats.

“Not to worry,” says the psychologist, standing beside me with a mug of steaming hot tea. “A little chaos never harmed anyone.”

Relieved, I take a deep breath and, knowing that I’ve just created the proper environment for an interesting and creative conversation, I ask my first question.

Tomasz Stawiszyński: Just before coming here, I visited the excellent bookstore Moe’s Books, where I saw a huge shelf dedicated entirely to ‘Parenting’. Judging from your works and lectures, you wouldn’t recommend purchasing any of those books?

Alison Gopnik: Definitely not. The first chapter of my book The Gardener and the Carpenter is called “Against Parenting”. It turns out that in the English language, the word ‘parenting’ didn’t actually turn up until the 1970s. There had always been parents – ‘mother’ and ‘father’ are among the oldest English words – but ‘parenting’ as this verb, this activity, is a very recent invention. And so is the idea that you should go out and read books and get expertise in order to learn how to raise children – it’s a recent development. I think it’s mostly been a bad one.

Why?

It presents us with a picture of caregiving that is not only inaccurate, but also morally and practically useless. It also causes a lot of guilt and anxiety, and at the same time doesn’t make the lives of children and parents any better.

So why has it become so popular?

For most of history, children were raised mainly by older siblings. This meant that younger siblings had more company, while the older ones were able to get the experience of caring for younger brothers, sisters, cousins and so forth well before they themselves had progeny. Today we have the first generation of people who at 35 years of age have never held a baby in their arms. When they become parents, they’re disorientated. Also there’s been another development, particularly in the last 10 years, which I call the rise of the intellectual and educational meritocracy. The middle class thinks that getting as much education as possible ensures not only success but even survival. And that’s why we’ve ended up with a parental arms race.

Everybody wants to give their children some edge.

In feudal societies, everything revolved around inheritance. You had to make sure that your child was going to get the land. In industrial societies, people were concerned about which child was going to get the money. But in our post-industrial information society, it’s all about who is going to be smart, who is going to do well at school, who’s going to go to Harvard, who’s going to do well according to the rules of meritocracy. That’s the new measure of success. Hence the parenting impulse to start children on this route as early as possible.

Parents have this clear image of who their children should grow up into and they try to shape them according to that image. You have repeatedly pointed out that it is the worst possible model of raising a child.

Today there are two main ideas about childhood. First, childhood – early childhood in particular – is thought of as the most important period in the life of a human being, crucial for our development. The science has increasingly been lending support to this idea. Freud was ahead of his time, because he recognized that even very young children think and pay attention to what is going on; of course now modern science knows much more about children’s mental processes. The second idea is that children are shaped by their parents and we are determined by our early childhood, particularly by the things our parents did or didn’t do. The decisions that parents make are supposedly essential.

And are they not?

No. I think it’s a morally and philosophically misguided view. Think for a moment about caregiving. What is it really about? Surely it shouldn’t be about shaping children in order for them to come out in a particular way. We establish many different relationships with people, and those relationships don’t have and shouldn’t have any specific, strictly defined purpose.

There was an interesting debate on those issues at the turn of the 21st century. Judith Harris and Stephen Pinker criticized the psychoanalytical dogma that parents shape our personality. Nothing of the sort, they said, we are shaped by genes and our peers. Psychoanalytic-oriented researchers were very critical of that.

The first thing to say is that neither of those camps had science on their side, even though both of them were invoking it. It was a rather ideologically-driven debate. At the same time, some interesting research was quoted, mainly to do with behavioural genetics. Its main question goes: where does the high variability in the population come from? Take, for example, a bunch of four-year-olds that vary on some traits. Some of them have thick hair, the others not so much. How does that correlate with the baldness or otherwise of their parents? Of course we’re assuming that the traits of the parents are going to be passed on to their children. But from an evolutionary standpoint, you wouldn’t expect that at all. The evolutionary perspective states that each subsequent generation should have higher variability. Therefore being a good parent is not about replicating your traits and behaviours in the next generation, but about creating a space in which there are many more variable solutions. Consider what your intuition tells you: do you think that parents have done a good job if their children chose the same paths as they did, or if the children went in a completely different direction? When the parent is a carpenter and the child becomes a neuroscientist, that’s impressive. I’m speaking from my own experience as the mother of a carpenter, who I’m extremely proud of. If the mother is a psychologist and her son becomes a carpenter it means that the mother has given her child enough autonomy and a varied enough set of capacities that he could freely choose his profession instead of fulfilling someone else’s expectations.

The child was able to do something new, different and unexpected. Is that beneficial from an evolutionary perspective?

Yes. That’s part of the reason why I use the metaphor of the gardener or the farmer. You might think that a farmer should focus only on what he wants to grow. But we know from biology that this is a terrible strategy. Any monoculture is highly vulnerable when, for example, a plague comes or the climate changes. Whereas if you have much more variability, much more noise, much more capacity for exploration, then the system is going to be more resilient in the face of a changing environment. We are now aware of ecological triggers for human evolution. I like to say that once it wasn’t that humans caused climate change, it was that climate change caused humans. Because of that, we are now able to adapt to a much wider, more variable, more unpredictable range of environments than our closest primate relatives. The chimps are pretty much in the same place they always were, whereas we’re all over the globe, for the better or the worse of the planet. If all that is true – if a long childhood and caregiving allows us to have variability – then you shouldn’t expect high degrees of correlation between the traits of the parents and the traits of the children. That doesn’t mean that caregiving isn’t important! It is – if it enables more variability in the next generation, not if it’s about producing a desired outcome.

However, the debate that I mentioned was mostly about what shapes our personality; about the role our parents play versus genes and peer influence.

In general, a strict distinction between the genetic factors and the environmental factors is impossible, in biology as well as in psychology. We can’t even estimate the percentages. If you think about the simple biological mechanism of gene expression, there are all sorts of environmental effects influencing that process. I think that the ‘nature or nurture’ question is simply ill-posed. It’s like asking what makes things hot: well, a scientist would immediately tell you there are two different things, there’s temperature and there’s heat, and you’re confusing them. Another example is, what makes something alive? You can’t give a simple answer. There are a whole lot of complicated interdependencies and interactions between cells, and what we call life is a sum total of those processes. Singling out just one of them is a very seductive but fundamentally misconceived idea.

Maybe we should draw the line differently and say: some people claim parents are responsible for everything, some claim parents don’t matter at all. You would say neither of those statements is correct?

Right. The caregivers provide a context in which children are growing up. Even if it was possible to shape your children in a particular way, by doing that you would have defeated the whole purpose of childhood. Childhood is there to allow us to have a new generation that is going to see things and understand things in a new, different way. Evolution loves diversity. But for that diversity to happen, the previous generation must create favourable conditions. Once at one of my book readings someone said to me: “Oh, so are you saying that everything that my Asian parents did to make me successful was just a waste of time?” And the answer is: of course not! We are cultural beings, we are shaped by learning and by cultural transmissions. And that’s precisely what the caregivers are there for. Not just parents by the way, but also the grandparents, the aunts and uncles, all the elders. The wide networks of caregiving kin is, I think, something else that we’ve lost in our contemporary societies.

How do you create the best environment in which children can thrive?

Children need an environment that is rich and varied. Rich enough in physical things that they can manipulate and find out about, and in biological objects, like animals or plants. Most of all, they need a wide range of people who care about them, so that they can explore a wide range of possibilities. Relatives, not only parents, are of great importance here. I’ve been writing and reading a lot about grandparents – possibly because I am a grandmother myself – and it seems we increasingly recognize that their generation has been underappreciated. We are now more aware that children need contact with people older than their parents. It’s essential from an evolutionary perspective. And vice-versa, it’s important for older people to be involved in caregiving and to share their knowledge with the next generations.

What you are talking about is in today’s word a sort of luxury available only to the well-off members of the middle and upper class. Such people can afford to provide children with the diversity and variability you mentioned, and therefore to enhance their chances of success in later life. Not everybody has the means to do that.

There was recently an interview with the economist Raj Chetty on Ezra Klein’s podcast. The talk was about inequality and things we can do that would lessen the negative impact of it. Chetty’s advice was to intervene in the early period, in the first five years of life. We actually have a very good idea of what those interventions should look like. Take, for example, the Reggio Emilia approach. It is practiced in various Italian pre-schools, and it goes all the way back to the invention of kindergarten, more than a hundred years ago. A Reggio Emilia pre-school is like a village. Paid teachers are not aunts, cousins or grandmothers, but they’re serving the same function – they’re putting the child in a rich environment that the child can freely and safely explore. Introducing such practices into the system of mass education could significantly lower the impact of inequality; there is very good evidence for that. Interestingly enough, when this approach was initially evaluated, it turned out that after a few years the academic benefits seemed to peter out, so kids weren’t doing better at school – but they were doing better at life if you looked at them 30 years later.

You have often pointed out that the pre-school age of four to five years is unique, because that’s when our mind is best set for exploration.

The age of four to five years is when the brain’s development peaks. That’s when the greatest number of new synapses are being formed. Also at this age 60% of your energy is going to your brain. By comparison, when you’re an adult it’s about 20%. There have been many experiments suggesting that children at the age of four or five fare terrifically well when faced with problems that require unobvious solutions. When it comes to expected solutions, the adults are much better: they don’t get distracted, they’re faster, they’re more efficient. But they fail when it’s all about getting the unexpected outcome. It makes sense too from the evolutionary perspective. If you have a system that’s really efficient, doesn’t get distracted, can do things quickly and doesn’t focus on all the alternative ways of doing something, that system is not going to be as good at finding solutions that are further away. However, a system that is not yet fully developed can think more freely.

It would be great if we could find some balance between the two.

Well, proper development can solve this trade-off. I think there are other ways. Take religion. It’s interesting that if you look across cultures, you find similar rituals: people go on a retreat, they stay up all night drumming, or take some psychedelic-inducing drugs. In all those cases, the idea is that one has to, as it were, get back to a child-like state in order to be able to consider various problems from a different angle. Similar things happen in organizations if you bring in someone from a different field – for example, when a physicist must go and think about psychology. Children have a fresh perspective because they don’t know yet how the world works. That allows them to look at things differently and sometimes bring about astonishing innovations. Even as adults, either by intentionally putting our brains back in a state that is more child-like or simply by facing a disorienting situation when we lack knowledge, we can recapture that creative state. Of course, those fantastically creative four-year-olds couldn’t exist unless we had a lot of people who were willing to make them peanut butter sandwiches day after day, care for them and educate them. And you would not want to have four-year-olds running your department, your factories or the world.

Childhood is also a time of many difficult, often traumatic experiences. Do they really scar us for life? How can we get to grips with our earliest negative memories?

There’s some research about this. What matters is the extent to which people are conscious of those negative experiences. Those who don’t remember much about their childhood or talk about it vaguely are more vulnerable to the bad things that happened to them. On the other hand, the adults who can look back at their difficult childhoods, who understand what occurred and why, seem to be better at coping with it. The attachment theory suggests (quite consistently with the cognitive theory) that developing internal models of reality and the people around you is an important element of growing up.

You consider children as some sort of little scientist, constantly developing hypotheses, testing them and working out theories.

Not only little scientists, but little psychologists. Of course, when it comes to figuring out the workings of close human relationships, they basically have only their parents as a case study. So having a wider range of people around you can be helpful; there’s some evidence of that. The more possibilities for studying, the better. Certain problems, for example anxiety and depression, seem to involve the opposite of that, namely the narrowing of possibilities. With depression, people perceive themselves as hopeless and useless; in the case of anxiety, you focus only on the terrible things that are going to happen. That’s what I mean by a narrowing of possibilities and perspectives. Being able to explore more options, whether through cognitive therapy or things like meditation, shakes you out of that. Similar mechanisms help people deal with having a difficult childhood.

We must admit that something strange is happening with childhood in the West. On the one hand, childhood is seen as a crucial period and children are treated as especially sensitive and vulnerable. On the other hand, as you’ve mentioned, children are forced to participate in a rat race and compete for social status. They are fed drugs so that they fare better in schools. They face completely unrealistic expectations. And then there’s the third problem: children often must play the parts of adults. They are entered into beauty contests and literally swallowed by show-business.

Take a look at the culture of America, one of the richest countries in the world. The upper-middle class is constantly ridden with anxiety and guilt. Those people spend billions of dollars on books about parenting and on things that are going to give their children a step up. But at the same time, we have more children in poverty than any other Western country. Material deprivation isn’t even so much the point – the real issue is isolation and lack of connection. Many children are growing up without a network of caregivers: all they have is a single mother who is working three jobs a night. As a result, at both ends of this spectrum, childhood as this period of free exploration is getting squeezed. I’d like to mention another factor, which is the insane risk aversion. Because of it, children are not allowed to explore – they can’t walk down the street because something bad might happen to them.

You can see it especially in the university campuses. Any contact with people who have different views than yours can be considered ‘oppressive’.

I don’t think we have clear data about this, but it’s interesting that if you look at what teenagers are like, you see that there’s actually much less risky behaviour than there used to be. That applies to many aspects of their lives. The rate of teenage pregnancies has gone down, so has the rate of certain kinds of drug abuse or crime. However, what has gone up is anxiety.

Why?

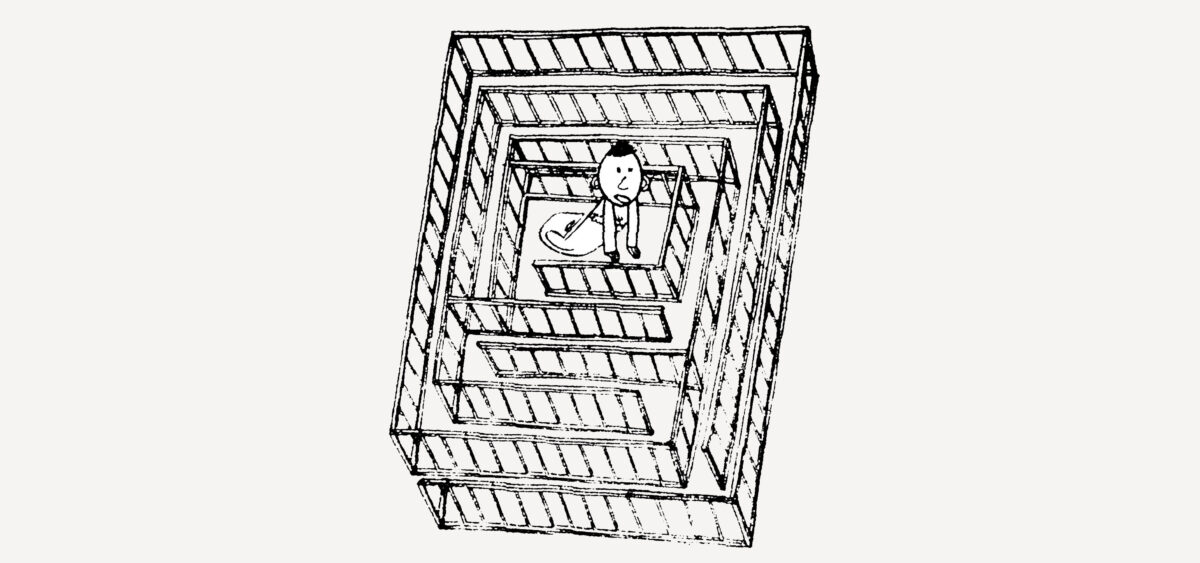

Well, we know that to some extent anxiety can be a result of misestimation of risk. For example, if your child takes risks and most of the time things come out well, it will learn to not be anxious. Taking risks teaches it how to cope with a threat. Whereas if the child isn’t allowed to do anything risky, if it is protected from ever taking action in the context of a threat, then it won’t develop a way of dealing with it. Here’s a classic experiment: you put the rat in the maze, it goes down one way, it gets shocked; it goes down the other way, it doesn’t get shocked. The rat quickly learns which way it needs to take in order to avoid the shock.

That’s very sensible.

Yes, but this strategy has a disadvantage. If the rat never goes that way again, he’ll never find out that maybe next time there won’t be a shock; maybe next time there will be food. Also, young rats actually prefer the arm of the maze that leads to the shock, but only if the mother is present. Similarly, three- and four-year-old children do all sorts of dangerous things, but they do it when they know that a caregiver is on hand, watching them. They treat this presence as a signal that nothing terrible is going to happen. Imagine, however, that the mother rat immediately says to the baby rat: “No, no, don’t go there, it’s too dangerous, you must never go there!” The baby rat is never actually going to learn that there are more possibilities. And that’s where anxiety begins. Incidentally, the best way to cure phobias is to expose people to the things that they’re frightened of. If you’re scared of snakes, you should spend a lot of time with them and see for yourself that the terrible outcomes you’ve been imagining don’t happen.

It’s no surprise that young people are more risk-averse and, at the same time, more anxious.

Understandably, those two things go together, especially in middle-class children. An analogy I like to use is the increase in allergies. The reason why there are more allergies is because there’s too much hygiene. The immune system needs training. Without sufficient exposure to threats, it goes into overdrive, even when there isn’t any danger. Same thing with anxiety. If you don’t have enough experience of overcoming threats, you end up overreacting. I think this combination of risk aversion and anxiety is a challenge, at least for the upper-middle-class children. Their parents’ fear of anything that might harm the children’s future careers is an important factor here.

But our economic system is extremely brutal. For many people, mere survival becomes the main goal. Therefore it’s not surprising that parents are scared of what’s going to happen to their children.

People have always wanted their children to succeed, but this narrow, focused, one-sided model about which we have been talking does more harm than good.

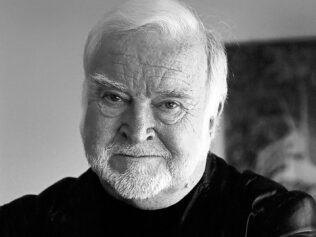

Alison Gopnik:

Psychologist and philosopher, famous for her work on children’s cognitive development. The author of The Scientist in the Crib and The Philosophical Baby. She has three children, three grandchildren and five siblings.

Introduction and biography translated by Jan Dzierzgowski