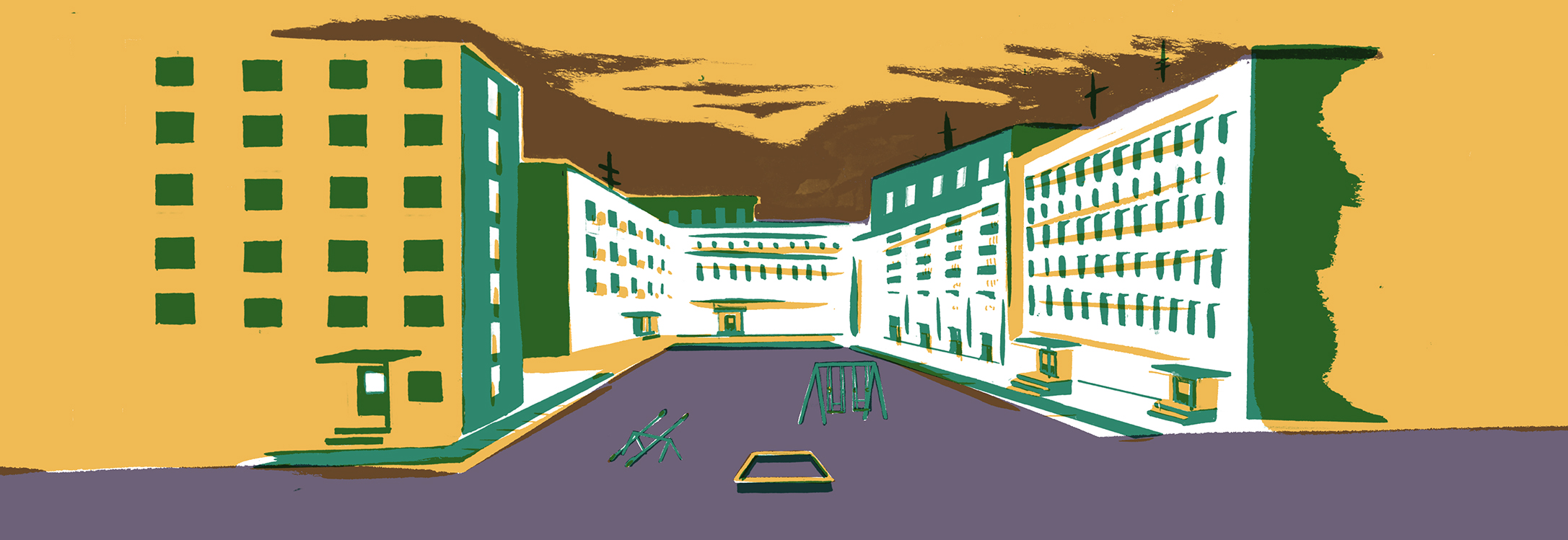

Over the years, Polish blocks of flats have developed a specific infrastructure of carpet hangers, dilapidated playgrounds, mud puddles so deep they could gobble down a car, infamous dumpsters, and thickets, in which many of us smoked our first cigarettes and experienced our first kisses. The architectural landscape of such blocks, with their variety of subcultures depending on the location of the buildings, their size, the neighbourhood, year of construction and many other factors, has also created less obvious, sociologically niche phenomena that many of us do not know existed.

Not all tower blocks were inhabited, so to speak, with the conventional one family per flat. There existed residential buildings that belonged entirely to institutions that rented them to their employees. One such block of flats, owned by the University of Łódż, was the 11-floor high rise building in the Widzew district. It was called the ‘Assistant Professors’ Hostel’. Contrary to the name, suggesting a temporary nature of accommodation, my mother and I lived there for six years. Those six years shifted between being entire normal and surreal to the extent that they felt as if they belonged in another universe.

The eerie space unfolded right on the doorsteps of each of the two staircases of the building. The entire ground floor was a maze of connected, transitive rooms known as ‘The Lodge’, which consisted of an office, a kitchen, a bathroom, a TV room and a corridor, where two janitors kept guard by the glass case full of apartment keys hanging on hooks. The keys were picked up by children returning from school before their parents came back from work. This distinguished us, the minor inhabitants of 2 Sarnia Street, from our schoolmates running around the yard with their keys on strings around their necks.

You could come to The Lodge to watch TV – at the end of the 1980s, not every family had a TV set of their own. One of the janitors used to hug us, little girls, and give us wet kisses when we came to see bedtime cartoons, but we just ran away giggling – no one had heard about paedophilia at the time. The higher the floor in our hostel, the more interesting it got. On each floor, there were microscopic studio apartments occupied by families of three, two-room flats for families of four, and three-room apartments – well, that was a bit more complicated.

In the Assistant Professors’ Hostel, there also lived families of two (like ours), too small to qualify to rent a small room with an even smaller kitchen. Single mothers with children, and unmarried people, as second-class tenants, were accommodated in larger flats, where we were always forced to share with strangers. During those six years – during which we changed apartments around five times – me and my mum shared the hall, bathroom and the kitchen of each of the flats we lived in with random people of both genders.

We made friends for life with one of our co-tenants, but most of the time our relationships with those whom we shared our living space with remained merely polite, as we toiled at having forced intimacy with people that we had nothing in common with. I remember the smell of their sweat, their greasy fingermarks on the door handles, the strange odours of their food in the kitchen, and their hair in the bathtubs. Such housing problems did not only occur in Poland in the immediate post-war…

The child residents of the Assistant Professors’ Hostel were a specific and outstanding group in the working-class, shady neighbourhood of Widzew. They usually stuck together, just like their parents: doctors, professors, tutors and assistant professors, who, despite financial ailments, formed an alien island in the district’s psychological tissue. Intellectual-spiritual kinship was conducive to making friends, families helped each other to look after their children and – even more importantly – to improve the standard of living.

Every now and then our block of flats was visited by the so-called ‘Committee of Social Affairs’, whose purpose was to intervene in cases of particularly difficult housing conditions for specific residents and apply for more convenient premises for them. In the days leading up to the arrival of the Committee, spectacular performances were rehearsed in many apartments, especially those in which unrelated people lived together by administrative allocation. Tenants of such apartments would invite all known children to run around screaming and demolishing the property, hallways were draped with strings full of dripping laundry, and in the kitchen food was prepared on a massive scale to lure cockroaches from the oven and make them disperse joyfully throughout the apartment.

Sometimes, flatmates would even fake dramatic arguments between one another to make the Committee realize the urgent need for action. Some of these performances brought positive results, allowing one of the tenants to move to more convenient digs. Those who did not succeed kept trying to make friends with their co-tenants, or quite the opposite – discreetly poisoned their food, pilfered their toothpaste or kept bringing the fictitious news that they were wanted on the telephone at the Lodge. Of course, no one ever called.

When I think about that time today, I have the feeling that I experienced a sense of community that could not be re-established nowadays – the intelligentsia inhabiting 2 Sarnia Street shared common life experiences and material deprivation. The years I spent there were the last years of the intelligentsia as a social class – it already began to disintegrate as democracy and capitalism started taking over the Polish social landscape. Some of my friends’ parents – university professors – suddenly switched to the insurance sector and started to build villas in the suburbs while their long-time marriages deteriorated. My friend’s dad – a chemist – started producing amphetamine in our hostel basement and ended up in prison. The dad of another friend – a geodesist – moved to another city to become the manager of a private factory producing paper boxes, as he couldn’t stand his family of four being crowded in less than 30 square metres.

When I think about the Assistant Professors’ Hostel today, I have the impression that I lived in some surreal, bittersweet fairy tale echoing Emir Kusturica’s Underground, where different, sometimes conflicted people – jammed in a small space and condemned to living together – would solve their problems and cope with this co-existence. With their tolerance, patience, fantasy and entrepreneurship, they built a micro-community that is now hard to find anywhere. The tower block on 2 Sarnia Street, with its cramped space, makeshift arrangements, ugliness – a place that people tried to domesticate alongside those belonging to that fated community – was like a ship that, despite all inconveniences, allowed us to sail safely through the turbulent reality of the social changes of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Before I wrote this article, I tapped my childhood address into Google. It still exists, under the name of ‘Sarnia Street Residential Building’. The photos on the website show the same cheap beige plywood furniture, dirty-yellow walls, oil-paint paneling… interiors out of style and time, beyond the present day. The Department of Social Affairs of the University of Łódż still offers the same types of rooms (e.g. a room for a single mother and child).

Nothing has changed for 30 years, and yet everything has changed.