For years, they traversed prairies, deserts and wetlands. They traveled through storms and floods, climbed peaks to admire mountain flowers. They were the first to understand the climate was changing and these changes needed to be countered. Meet Edith and Frederic Clements: itinerant ecologists, who helped revive a barren land and saved America from hunger.

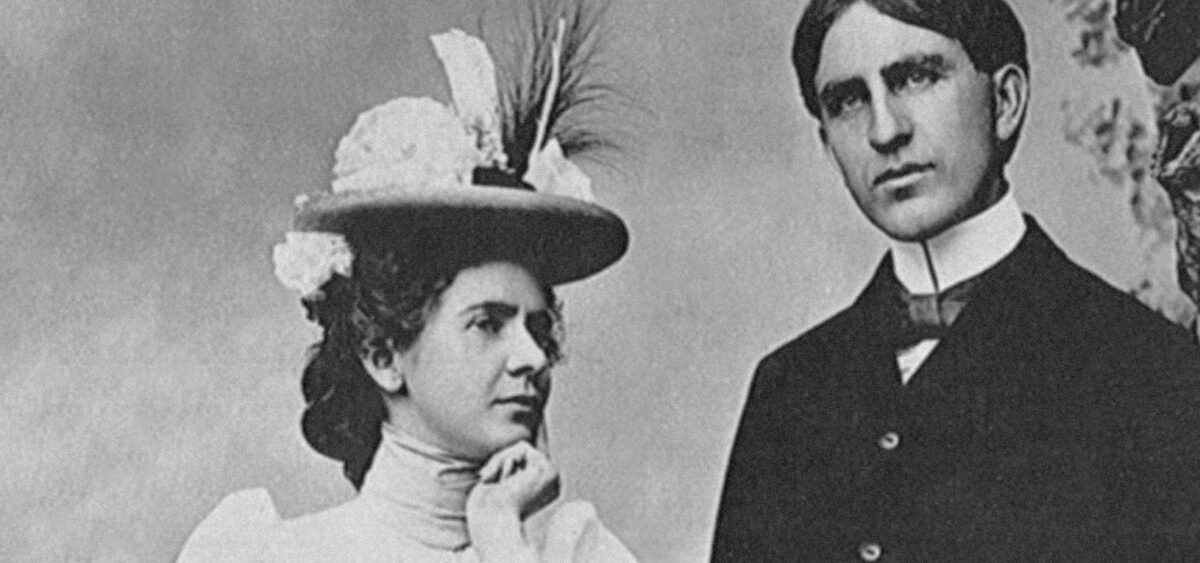

“Why wait?” he asked her on a spring day in 1899, after returning from a research trip on the prairie, somewhere north of Lincoln, Nebraska. It was a beautiful, sunny day. They had just found a pretty mimosa with pink, furry blossoms. Frederic was right, there was no reason to wait. They didn’t want to be apart. They had everything in common, especially their passion for exploring the world of plants and watching life unfold. Edith was supposed to go to Omaha on vacation, whereas Frederic was to stay on campus to teach summer courses. But, as she wrote years later, “the thought of separation was intolerable.” They met at the university in Lincoln. He was a lecturer, and she was still a student. In her free time, she was involved in the life of her sorority, played tennis, was captain of the basketball team and practiced fencing. At the end-of-year ball, Frederic got as many as three dances with her. That’s how it all began.

The Environmentalist Power Couple

They got married quickly and quietly. Even their closest friends found out after the fact. Both of them thought their families would approve of the decision. Their parents didn’t care much for festivities and shunned glamor. Marriage seemed like an obvious choice, after which they didn’t look back; they had no doubt. There was too much to do together; awaiting them was a life almost always on the road, in the field, in awe of nature.

Was it a great love story? Without question. Although Edith and Frederic Clements left very little writing that was intimate in character, their letters testify to the passion of the affection. Based on Edith’s memoir Adventures in Ecology: Half a million miles…from mud to macadam, published in 1960—fifteen years after Frederic’s death—it can be assumed that their life together was a wonderful adventure. It sparkled with extraordinary events, Full of insatiable curiosity, travel, work, and research, as well as a visionary spirit, rare among scientists. Today, the memory of the Clements has been painstakingly restored, but in the 1930s and 40s they were well-known and—called upon for help—all over America. Their joint achievement in biology and pioneering work in ecology were compared to the discoveries in chemistry and physics made by Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her husband, Pierre. It would be hard to find a third such power couple in the history of science. Although Edith had no illusions of her circumstances—she wrote that she worked for free alongside her husband—they operated as a team, Frederic’s accomplishments wouldn’t have existed without her. He didn’t try to overshadow his wife. She was his equal partner; Edith didn’t take a backseat. Over the years, they drove five-hundred thousand miles on research trips, and it was usually her behind the wheel.

An Omnipresent Evil

For Americans living in the South in 1931, it was easy to believe that the apocalypse had arrived. The calamity began with a series of drops that hit the Midwest and southern prairies of the country. Crops were dying before the eyes of helpless farmers. Then the dust storms started. Referred to as “black blizzards,” the number of these dirty dusters grew rapidly, from fourteen in 1932, to as many as thirty-eight in a year later. By 1934, the drought covered as much as three-quarters of the country, affecting twenty-seven states.

The heaviest storms came in 1935, and it was estimated that winds blew away 850 million tons of arid soil in the US that year. Those who survived said none of the accounts of that nightmare weren’t exaggerated. The suffocating dust in darkness obscured everything. Everything was wrapped in it. A blizzard would raise dry earth for days. Dust got into people’s eyes, filled every crack and fissure. It submerged entire households—as if in a flood of sand. Even at noon, you couldn’t see the sun, the swirling clouds extinguishing the light of day. The effect was surreal: the people of the plains felt as if the wind carried some dark force that was crushing them. The dust was inescapable—people would run, and it would follow. It shook their wooden houses, where they would huddle in the darkness. Children couldn’t play outside, since the air was deadly. Survivors described the dusty wind as an omnipresent evil.

The land on which human life depended, took revenge for years of over-intensive farming and soil erosion. Now, the fields could not be cultivated and the cattle, with nowhere to graze, starved to death. Once proud working farmers had nothing to feed their children. Then the hares and grasshoppers arrived, occupying the dry soil in alarming numbers.

This was an ecological disaster of biblical proportions, which lasted almost a decade and would become known as the Dust Bowl. It was the greatest man-made catastrophe in US history, driven by a vision of easy money and encouraged by government policy. Collectively generated and experienced on a mass scale, some 260 million acres of farming land became either entirely or partly barren, destroying land considered to be the country’s breadbasket. Thousands of people fled, abandoning fields and homes destroyed by dust drifts. Many others fell ill, but some endured. The calamity unfolded quickly, after only thirty to forty years of soil overexploitation, bringing one of North America’s largest ecosystems to the brink of collapse.

The Great Depression

This crisis coincided with the Great Depression and the collapse of the American economy. After Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, far-reaching plans for national reform and recovery were set in motion. One of them was the agriculture bill known as the Taylor Grazing Act, enabling the government to reserve 140 million acres of land for grazing, which was strictly controlled. To help farmers, the government bought their cattle and paid compensation. It also founded special agencies responsible for monitoring soil erosion, introducing new farming methods, and developing agriculture that was less detrimental to the environment—what would today be described as sustainable. Programs were also launched to reforest areas previously stripped of trees for the construction of large farms. The drought was expected to last until 1939, when regular rains would eventually return.

The main concern in those years was how to let the land regenerate, while ensuring it wouldn’t be destroyed that way again. Enter Frederic and Edith Clements. He was already a respected ecologist in the US, affiliated with the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C. Of his two major works Research Methods in Ecology and Plant Succession—published in 1905 and 1916, respectively—the former is a groundbreaking study on ways to observe and recognize plant life, whereas the latter—co-authored with his wife—analyzes the developmental process of different types of plants. It describes the order in which bare land is first occupied by annuals, then grasses, shrubs, and trees all in conjunction with climatic factors. Edith recalled how typewritten pages took up all the tables in their small research lab, and weighed a total of fifteen pounds.

Frederic was an idealistic ecologist, viewing nature as a complex ecosystem governed by strict laws and causal relationships. He looked at it holistically as an intricate network of interdependencies. And in thinking about and studying nature from this perspective, he and his wife were the first. When desperate farmers were trying to understand the reasons behind the catastrophic Dust Bowl, the Clements provided a clear explanation: too much plowing, overgrazing, and climate change—a recipe for disaster. Previously, the couple had spent years observing how ecosystems evolved. They knew about climatic cycles and understood why some plants disappeared and others appeared, in being better adapted to new conditions. Recognizing the trajectory of these changes, the Clementses would travel over mountains and across plains, examining droughts and deserts, then return to the barren lands and observe great floods and their consequences. They identified the principles that governed these processes, perceiving nature as a form of life with its own internal logic, in which one could predict the future with high probability.

The Nature of Nature

The Roosevelt administration appointed Frederic a consultant to the Bureau of Forestry and the Soil Conservation Service of the Department of Agriculture operated according to his scientific recommendations. He stuck to his convictions; he did not support all government decisions, but he was flexible with his findings to finally create a set of practical guidelines for farmers: what to sow and plant, in what order, and how to cultivate it in order to retain water in the soil, enabling its regeneration, which was essential for growing crops. Dunes strewn with wind-blown soil were leveled, and cacti that had spread during the drought were removed. Grasses were planted instead, enabling water retention before introducing corn and other produce. Frederic also recommended controlled grazing: a method which discouraged animals from eating the seeds and roots in the soil. America’s breadbasket slowly recovered and harvest was again possible.

Subsequent generations of soil scientists and prairie farm managers owe it to Frederic for these solutions, and many agriculturists continue to apply them. And while the mid-20th century scientific and ecologists considered him too rigid in his views, even wrong in his interpretation of the role of ecosystems in the evolution of organisms, his achievements are gaining increasing recognition today. This is primarily due to his fundamental findings on plant vegetation and pioneering philosophical studies on the nature of nature itself.

On the Road with the Clementses

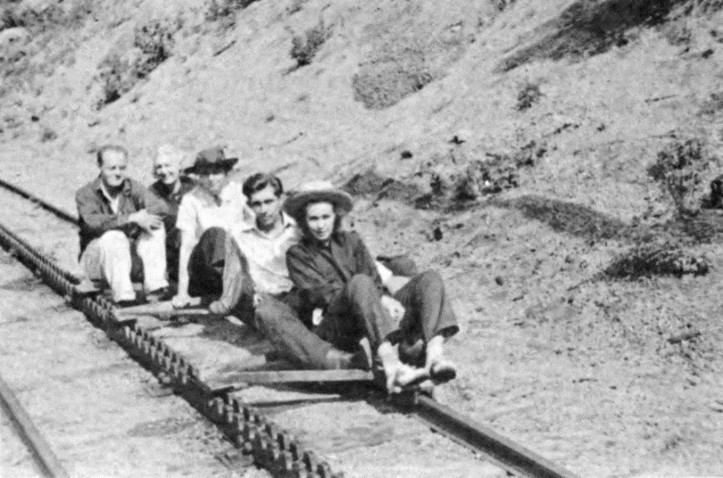

In the new century, a growing interest in the “herstory” of science—as in, the role of women in research development, discoveries and inventions—has made it possible to revisit the legacy of Edith Clements and her contribution to field research conducted together with her husband. In Adventures in Ecology, Edith didn’t paint the whole picture when it came to her own achievements. Writing with a bold tone, she diverted attention from the role she played in the study of American flora. This amusing and anecdote-filled account shares research experiences and focuses on how they spent most of their life on the road. They traveled across rarely-trodden routes through the American wilderness. Their story consists of a long list of failures and accidents, like pulling cars out of marshes, lakes, and sand drifts. Edith, who was usually behind the wheel, learned to drive on slippery mud, ice, and dunes. She describes these recurring accidents with swagger, always jokingly, as if they were utterly unperturbed by the obstacles they encountered. After all, it was because of them that their honeymoon was extended. Clearly, they both enjoyed not only the scientific but also the adventurous aspects of their work and relationship: mountain climbing to observe plants on high peaks, trudging through snow drifts without proper gear, sleeping in random places; in cabins and barns in the middle of nowhere, hammocks around trees, or guest houses run by Mormons—just wherever they could.

The Clementses traveled the length and breadth of the States. The Dust Bowl was not a surprise; they had already seen all sorts of smaller-scale disasters throughout the whole country. When comparing their work as plant ecologists to other scientific professions—since it was poorly understood at the time—Edith explained that their job consisted of observing vegetation, making inferences based on past experiences, and predicting the environmental future. It also involved analyzing simple organisms, which, in turn, required travel—to study them closely, they had to reach deserts and cold rocky summits. Edith attached great importance to experimental farming as a research method: she observed plant vegetation in controlled conditions, with adjusted lighting, humidity, and temperature. These were pioneering attempts at an empirical description of the relationship between living organisms and the environment in which they lived and evolved. Edith viewed ecology as part of the social sciences, conducting research for the common good and a better understanding of humanity. She wanted to apply the laws of nature to interpersonal relations, and found clues on how to tackle the greatest challenges facing civilization. She was a visionary. Nowadays, when climate change has become a fundamental concern for the future of our species, Edith Clements might be cited as the first woman ecologist who understood that human life and the life of the planet are intimately connected, and that the answers to questions of what is to come are worth seeking in nature.

The difficulties didn’t discourage her, they were her fuel. As she put it in her account of a field trip to scorching Dakota:

Perspiration pours into my eyes and down my nose, and every fresh gust threatens to send the entire outfit, including myself skittering down the steep slope. By this time, I am a wreck; by the end of the day I am several wrecks. I tell Frederic that I am offering myself a burnt sacrifice on the altar of his love of work. He looks at my peeled nose and red neck and assents as calmly as though a mere wife were a small price to pay for the rewards of scientific research.

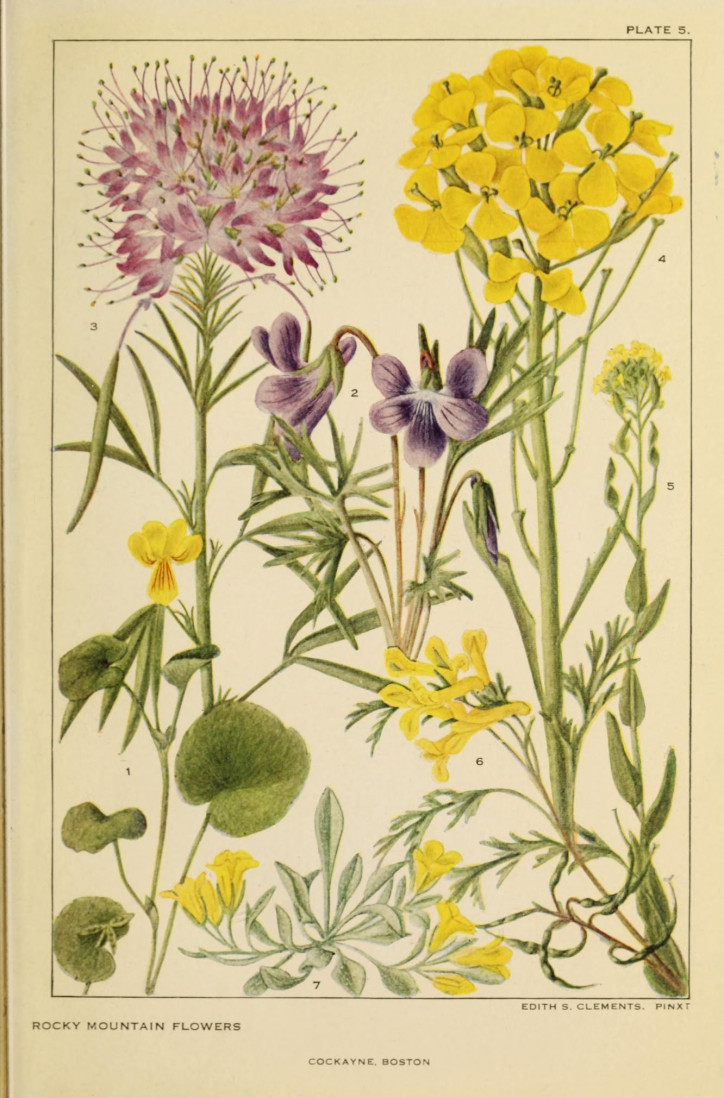

The Clementses were capable of enjoying their collaborative work with good humor, fully aware of the disparity in professional status between them. But according to Edith’s notes, she had no regrets. There was too much going on; she was too consumed with findings and discoveries to gripe about the injustice of her position. It appears that as far as their relationship was concerned, the Clementses were equals. In the field, they were a perfectly complementary duo. Both their names appear on their most memorable achievement, Rocky Mountain Flowers: An Illustrated Guide for Plantlovers and Plant-users (1914). Edith had a talent for art. Although they had a portable camera, which they would set up even on steep slopes, she spent hours on detailed drawings of plants, full of color and life, which she called their portraits. Although modernism was in vogue at the time, with the triumphs of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings of flowers as symbols of femininity, Edith stayed true to precise realism. She wanted to accurately represent each petal, every symmetrical structure making up a leaf. Her vibrant illustrations can be admired today by everyone for free in the public domain. The Rocky Mountain Flowers compendium has become a staple of field research for scientists, as well as amateurs. Later, the Clementses completed similar studies of plants in the West Coast and American Midwest. Edith’s drawings made waves—before World War II, they were published and popularized by, among others, the National Geographic magazine.

A Laboratory in the Mountains

They were peers, both born in 1874—Frederic in Lincoln, Nebraska; Edith in Albany, New York. Her father, George Schwartz, was a pork packer. The family moved to Omaha, where Edith grew up the third of seven children. She was a very good student, just as was expected. She was very well-liked—independent, cheerful, pretty, and helpful. She was popular in high school. At college in Minnesota, Edith studied business for a year, then transferred to the University of Nebraska, in Lincoln. An outstanding student, after graduation she got an offer to teach German. Frederic, by then her husband, persuaded her to take up botany and ecology instead. He impressed her intellectually; he could read three novels a day and had the memory of an elephant.

After the wedding, they took a trip to Pikes Peak—a summit in Colorado, where a few summer houses stood. It was there that they came up with the idea for an experimental ecological research station that would operate in the mountains throughout the summer. They started by erecting a simple building with two small rooms, financed with a two-hundred dollar loan, expanding it over time with grants and the money they earned from their plant guides. Their Alpine Laboratory would operate for over forty years, with support from the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

In 1906, Edith became the first woman at the University of Nebraska to hold a PhD after completing her doctoral studies in botany. It was then that the Clementses began admitting students into their summer laboratory—generations of researchers who later went onto brilliant careers studied there. When Frederic became dean of the University of Minnesota’s Department of Botany the following year, Edith accepted a lower-level job there, but openly criticized discrimination against women in science. She was part of the American suffrage movement and was conscious of her own professional standing, which paid off. In 1911, she and her husband received an invitation for a research trip to Europe—a visit which proved successful for both of them. Edith established valuable contact in Germany due to her excellent grasp of the language, while Frederic shone among the British scientists. Thus began their research partnerships and friendships that would last decades. In letters to her family, Edith vividly described scientific people, creating psychological portraits of them, and when top European botanists visited the US, they spent over a week at the Clementses’ laboratory.

Edith was included in the Who’s Who in America in 1914, where a description of her scientific achievements found its place amongst the biographies of the most important living Americans. When Frederic was offered a job at the Carnegie Institution in 1917, they moved to Arizona, and then to California. They spent the next few years on the road, traveling all over the country. Edith was the better driver, but the main reason she was the one behind the wheel during long trips, in an automobile that was always breaking down, was because of Frederic’s illness, which they kept secret. He suffered from diabetes and hyper adrenaline disorder, which had a destructive effect on his body—this was when hormone treatments were not yet commonly known. His illness and the need for constant care was another reason the couple was inseparable. After Frederic’s death in 1945, Edith described in letters to friends about her despair and how she had completely lost her sense of purpose in life. With the exception of three days, for which they were separated soon after their marriage, the Clementses had spent forty-six years together, day in, day out. He asked her not to leave him. She kept her word.

The World is a Plant

Although Edith made sure that Frederic’s final research was published, the scientific community did not treat them favorably. At that time, major trends in botany were neo-Darwinism and genetics. Many researchers dismissed the Clementses’ findings, claiming environmental factors do not play such a significant role in the evolution of organisms. They opposed the holistic approach to ecosystems as complex and intricately entangled life forms. Frederic’s research papers failed to find a home for a long time. No university wanted them. Eventually, a former student archived them in Texas. Since Edith was taking care of her sick sister, it wasn’t until she was in her eighties that she returned to writing. It was then that she published Adventures in Ecology, an entertaining look back at the daring life of a couple of tireless explorers of nature.

Although she intended to, Edith never managed to write a serious dual biography depicting the research crisis and difficulties they faced. It’s a pity, since her memoir, which reads more like an adventure book, doesn’t provide an entirely honest account of the sacrifices the Clementses’ made, nor do justice to Edith’s own achievements —the meager traces she left behind made it hard for historians to determine the true extent of her contribution for years. She died in 1971 and had no children. Edith and Frederic’s alma mater in Nebraska refused to archive their research, but they were readily accepted by the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that Edith Clements’s scientific output began to be recognized and appreciated. Her texts were included in anthologies of major American women scholars. The value of Edith and Frederic’s work in the development of ecology is indisputable, and scientists agree on the fundamental and pioneering importance of their research. It is because of these emissaries of the field that we now conceive of plants as individual and sophisticated organisms, whose evolution depends on a wide variety of factors. And, importantly, we’re aware that our behavior as people has an impact on the future.

In writing this article, I mostly relied on the following books:

- Clements, Edith, “Adventures in Ecology. Half a Million Miles: From Mud to Macadam” (Pageant Press, 1960)

- Edith S. Clements and Frederic Clements, “Rocky Mountain Flowers: An Illustrated Guide for Plant-lovers and Plant-users” (Nabu Press, 2012)

- Oberg, John H., “Founders of Plant Ecology: Frederic and Edith Clements” (University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 2019)

This translation was re-edited for context and accuracy on December 1, 2022.