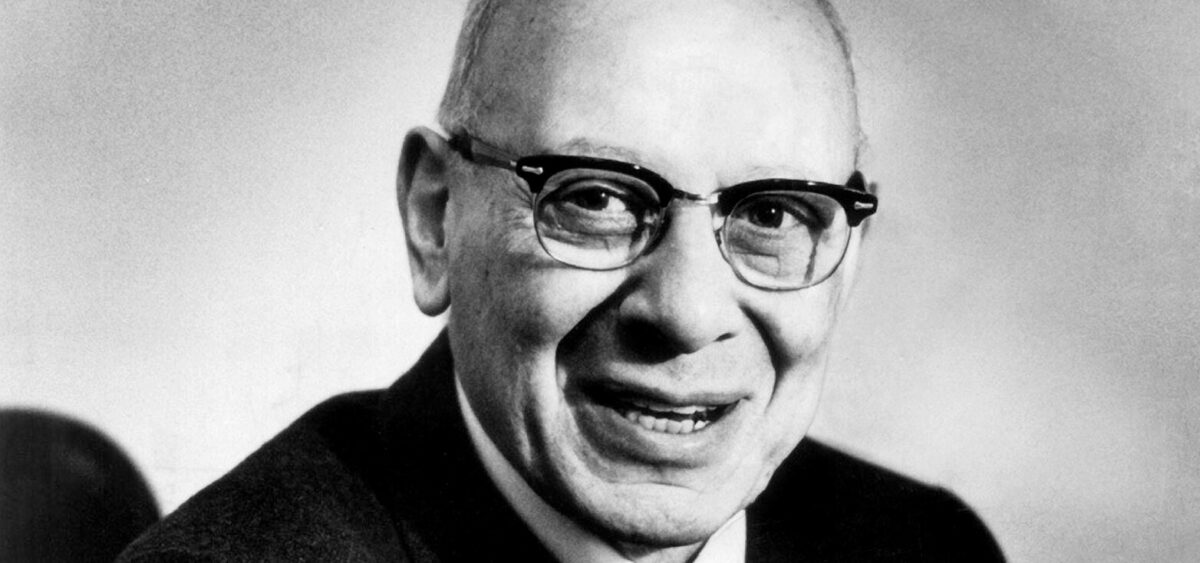

Child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim wanted to heal with fairy tales, care and kindness. His psychiatric hospital had no bars on the windows. He intended for his young patients to recover in a pleasant, calm environment. The story of the good doctor sounds like a fairy tale. And who knows – perhaps it was.

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, beyond the Danube, Bruno Bettelheim was born. If his life were framed as a fairy tale, it would resemble a saga of a fight against evil – the kind you wouldn’t even read about in the collections of the Brothers Grimm. It would be a tale of the traces that this evil leaves on the human psyche, and how difficult experiences can be turned into something positive. Something enchanting. This fairy tale doesn’t have a happy ending, although it ended in precisely the way the protagonist wanted.

Rescue from across the ocean

Bettelheim was born on 28th August 1903 in Vienna, into a wealthy, secularized Jewish family. We don’t know which fairy tales he was told as a child, but it’s safe to assume that his mother or nanny read him Grimms’ Fairy Tales – nowadays, it’s a classic, and at the time it was an extremely popular collection of folk tales combining magic and fantasy with fear and cruelty. As Celeste Fremon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Bettelheim acknowledged years later that his favourite fairy tale was Hansel and Gretel because “the boy and the girl needed each other”. Perhaps it was his willingness to work together with other young people that prompted the teenage Bettelheim to join Vienna’s Jung-Wandervogel (‘Young Migratory Bird’) – a left-wing, pacifist youth movement – in 1917. Like the other members of the group, he rebelled against authoritarian families and the strict disciplinarian approach of Austrian schools.

Bettelheim’s other passion at that age was psychoanalysis – a new and intriguing discipline of study producing graduates who were boldly venturing into the hidden world of human instincts and desires. He was also fascinated by the creator of psychoanalysis himself, Sigmund Freud, and hugely influenced by his work. Soon, Bettelheim began studying philosophy and art history at the University of Vienna. However, after his father’s death, he left university to take care of the family sawmill, not returning to his studies until his thirties.

In the 1930s, Bettelheim and his wife Gina took a patient, Patsy, into their home. The young girl came from a wealthy New York family and was suspected of having autism. Bettelheim intended to treat the child with psychoanalysis and to base his doctoral thesis in psychology on the case. As Patsy’s condition improved, her guardian discovered his calling. And that’s when Evil appeared on the scene. In March 1938, Hitler annexed Austria and began sending Jews and political opponents living there to the concentration camps. Bettelheim went first to Dachau and then to Buchenwald. He was saved by Eleanor Roosevelt, who was notified of the situation by Patsy’s parents. In April 1939, the wife of the President of the United States managed to extract Bettelheim from the nightmare of the camps. A penniless refugee, he boarded a ship to New York to join his wife, who had emigrated earlier. But their marriage didn’t last long.

Bettelheim was able to return to academia thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation, which helped resettle European scientists. He was hired by the University of Chicago, where he became an assistant to Ralph Tyler and studied methods of teaching art in high schools. He worked there until 1941.

No locks or bars

“If he had a genius, it was his uncanny ability to find healing and hope in circumstances in which others could see only despair,” wrote Celeste Fremon, the journalist to whom Bettelheim gave his last interview, in the Los Angeles Times in January 1991. As Fremon noted, “[h]e used his own horrific experiences as a prisoner of the Nazis in Dachau and Buchenwald to draw conclusions about the nature of human suffering that would help him heal the psychic wounds of others.” She also mentioned the essay “Individual and Mass Behavior in Extreme Situations”, which Bettelheim published in autumn 1943, winning him immediate renown but also arousing controversy. The essay contained persuasive arguments for the human ability to adapt to the extreme living conditions in concentration camps and described the impact of Nazi terror on prisoners’ personalities. However, there was much objection to Bettelheim’s suggestion that Jews had provoked some of the Nazis’ actions themselves.

The years 1941 and 1944 brought two important changes in Bettelheim’s life: his wedding to Gertrude Weinfeld, also an immigrant from Vienna, and his employment as the director of the Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School, an institution for children with severe emotional disorders. He got the job thanks to a recommendation from Ralph Tyler that had led the University of Chicago to appoint Bettelheim a professor of psychology.

In the process of developing his own form of therapy for children, he drew on his experiences from the camps, analysing the influence of the environment on mental health. He concluded that since the dehumanizing approach of the Nazis led to the disintegration of prisoners’ personalities, care, attention and good conditions should have the opposite effect. He therefore decided to turn the traditional psychiatric facility into a resort. The bars were removed from the windows, and the locks from the doors. The only locks that remained were those inside the doors – now it was visitors who needed permission to enter, and the young patients were allowed to leave their rooms whenever they wanted. Meals were served on porcelain instead of plastic plates, and meat could be cut with a knife, rather than having to be torn apart with a spoon. Pictures were hung on the walls.

This unusual strategy, combined with psychotherapy, worked. Celeste Fremon cited data from Bettelheim and his colleagues claiming that in the 30 years Bettelheim spent at the Orthogenic School, more than 85% of patients previously deemed ‘hopeless cases’ returned to active participation in society. Only after Bettelheim’s death did it emerge that, unfortunately, this fairy-tale image of the school was deeply flawed.

While working at the school, Bettelheim published several books, including The Empty Fortress (1967) about children with autism, and The Children of the Dream (1969) about raising children communally on an Israeli kibbutz. In 1973, at the age of 70, he retired. He and his wife moved to Palo Alto, but he remained active as a writer and lecturer. His monumental book published in 1976, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, became a bestseller.

Be like Little Red Riding Hood

“As an educator and therapist of severely disturbed children, my main task was to restore meaning to their lives,” wrote Bettelheim in the introduction to The Uses of Enchantment. “[…] I was confronted with the problem of deducing what experiences in a child’s life are most suited to promote his ability to find meaning in his life; to endow life in general with more meaning. Regarding this task, nothing is more important than the impact of parents and others who take care of the child; second in importance is our cultural heritage, when transmitted to the child in the right manner. When children are young, it is literature that carries such information best.” He claimed that it was the folk fairy tales – the original, ancient ones laced with cruelty, without embellishments or intrusive didacticism – that had the power to make an impact, because they were derived from the initiation rites of primitive cultures and rituals preparing children to enter the adult stage of life. According to Bettelheim, these fairy tales served a therapeutic function, helping children cope with traumas and emotional problems.

He had no doubt that “[f]airy tales are unique, not only as a form of literature, but as works of art which are fully comprehensible to the child, as no other form of art is. As with all great art, the fairy tale’s deepest meaning will be different for each person, and different for the same person at various moments in his life. The child will extract different meaning from the same fairy tale, depending on his interests and needs of the moment. When given the chance, he will return to the same tale when he is ready to enlarge on old meanings, or replace them with new ones.” Children unconsciously identify with the main character of the story. By experiencing the hero’s adventures, “they find solutions and patterns of behaviour that will serve them in childhood, adolescence, and even into their adult life,” adds Mariola Lekszycka in her article “Babciu, a dlaczego masz takie wielkie kły?, czyli percepcja baśni w trzech dyskursach” [Grandmother, what big teeth you have! The perception of fairy tales in three discourses], published in the anthology Rejestry kultury [Cultural Registers].

The kinds of problems that a child might confront or overcome through a fairy tale include loneliness, exclusion, low self-esteem, sibling rivalry, anger, and even the loss of a parent and fear of abandonment or death. The fairy tale prepares a young audience for “the changes to come: taking on adult duties, including a new social and cultural role, sexual initiation and planning a family,” concludes Lekszycka. She emphasizes that the fear experienced by a child rarely takes the form of a confession revealing that they are scared of their own death, or that of a parent. Much more often, this fear manifests itself symbolically when the child doesn’t want to sleep in their own bed or starts to be afraid of the dark.

But a fairy tale is not a prescription. It doesn’t provide ready-made solutions, but shows the consequences of various actions, forcing readers to discover meanings for themselves. This, in turn, leads to the regulation of fears and anxieties. This is the role played by the final sentence of most fairy tales: “And they lived happily ever after.” The child, accompanying the protagonist and overcoming all the adversities alongside them, undergoes a psychological initiation, and the formula ending the story gives them strength and faith in the meaning of their own efforts in life.

“This is exactly the message that fairy tales get across to the child in manifold form: that a struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable, is an intrinsic part of human existence – but that if one does not shy away, but steadfastly meets unexpected and often unjust hardships, one masters all obstacles and at the end emerges victorious,” states Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment.

A good example is the story of Little Red Riding Hood. According to Bettelheim’s interpretation, the adolescent girl in the fairy tale embodies the struggle between the child’s principle of pleasure and the budding adult’s principle of reality. The symbol of this struggle is the colour red, which suggests turbulent emotions associated with gender, including sex appeal. In Bettelheim’s opinion, “[i]t is as if [she] is trying to understand the contradictory nature of the male by experiencing all aspects of his personality: the selfish, asocial, violent, potentially destructive tendencies of the id (the wolf); the unselfish, social, thoughtful, and protective propensities of the ego (the hunter).” The protagonist’s act of stuffing stones into the wolf’s belly after her release is, according to Bettelheim, the girl’s first independent decision, introducing her to adult life.

Plastic bag and barbiturates

Bettelheim himself made an independent decision on 13th March 1990. Tormented by grief since his wife had died six years earlier, struggling with mobility problems and unable to write after suffering a stroke in 1987, he chose death for himself. Staff at his nursing home in Silver Spring, Maryland found him, as Celeste Fremon describes it, with “a plastic bag over his head and barbiturates in his bloodstream.”

A few months earlier, Bettelheim had given Fremon his last interview. He admitted that he was considering suicide and was planning to travel to the Netherlands so that a doctor friend of his could administer a lethal injection. “Part of the problem,” he said, “is that our society doesn’t know what to do with old people. […] There are societies where the old are venerated, like in China. The Israeli kibbutzim make very special arrangements so that their old people remain active according to their abilities. They are not relegated to some old people’s home or some retirement home, as is done here. It is very hard to go on living if you no longer feel useful or very important.” He was not afraid of death, only suffering. Towards the end of his life, he was still collaborating with local therapists and taking part in public appearances – in May 1989, he became an honorary member of the Los Angeles Psychoanalytic Society and Institute, and during his rare speeches, he spoke with humour about his friends (including psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, and Woody Allen, whose film Zelig featured Bettelheim playing himself). But ultimately, he chose suicide. Despite the fact that he had spent much of his career focusing on fairy tales, he didn’t believe stories about the afterlife. He believed only in the love that gave life meaning, which had been taken away from him by the death of his wife.

Doctor ‘Brutalheim’

Like any fairy tale, the story of Bruno Bettelheim has several versions. After his death, it emerged that the respected psychoanalyst, educator and lecturer had fabricated parts of his education. When he started working at the University of Chicago, he said he had a doctorate in art history and psychology, but no proof of this qualification existed. He also claimed to be a certified psychoanalyst, which was also untrue. Nor was he a student of Freud. Richard Pollak, author of The Creation of Doctor B.: A Biography of Bruno Bettelheim (1997), has called him a pathological liar and accused him of plagiarism. Apparently, Bettelheim copied large fragments of The Uses of Enchantment from Julius Heuscher’s A Psychiatric Study of Myths and Fairy Tales: Their Origin, Meaning and Usefulness (1963). Subsequent researchers have confirmed the controversy surrounding Bettelheim’s academic degrees.

Meanwhile, much weightier issues have arisen in the form of accusations of mental and physical violence used against the patients of the Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School. Contrary to what Bettelheim declared during his last interview with Celeste Fremon – “one has to create better people to create a better world. That is what I tried to do” – his former patients have spoken of abuse and intimidation. “I lived for years in terror of his beatings,” confessed Ronald Angres in an article in Commentary magazine written shortly after Bettelheim’s death, adding: “[…] I never knew when he would hit me, or for what, or how savagely.” The majority of the parents of patients from the Orthogenic School have said they don’t believe the revelations about Bettelheim, mainly due to his strong standing as a psychologist. And while the psychiatrists of Chicago referred to their colleague by the nickname ‘Brutalheim’, they did nothing to intervene effectively on behalf of the school’s patients.

Years later, one of Bettelheim’s famous theories also collapsed. He had compared autistic children to concentration camp prisoners who, in a similar way, flee into apathy to protect themselves from the hostile world. In the case of childhood autism, this hostile world was supposedly constituted by the ‘refrigerator mother’. Like the fairy-tale wicked stepmother, she is incapable of loving her child, and perhaps even wishes they didn’t exist. It is hard to imagine the sense of despair and guilt experienced by the women who believed this dogma. But Bettelheim also laid the blame on ‘absent’ fathers, a topic he explored in The Empty Fortress. Such was the state of knowledge in the 1940s and ’50s. Under the influence of psychoanalysis, the source of every mental state was sought in the parent-child relationship. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the psychogenetic theory of autism started to be rejected. Today, the causes of this disorder are thought to be genetic mutations, complications and viral infections during pregnancy, and autoimmune diseases in the mother.

Herstory

Although 45 years have passed since the first edition of The Uses of Enchantment, Bettelheim’s theory is still taken into account in research on fairy tales. Nonetheless, some of his interpretations have received widespread criticism. The aforementioned reading of the story of Little Red Riding Hood (also known as Little Red Cap) has evoked particularly strong emotions. Bettelheim wrote: “Little Red Cap’s danger is her budding sexuality, for which she is not yet emotionally mature enough.” The helpless girl is thus simultaneously subject to the attack of unbridled male lust, which is personified by the wolf, and reliant on the help of another male figure, the patriarchal guardian: the hunter.

In the 1970s, feminist researchers began to pay attention to the stereotype of the social role of women perpetuated by this interpretation. A ‘retelling’ trend emerged, involving the creation of new versions of fairy tales, turning ‘history’ into ‘herstory’. Authors such as Angela Carter, Tanith Lee and Emma Donoghue brought female characters to the fore, giving them strength and agency. In Angela Carter’s short story The Company of Wolves, Little Red Riding Hood is indistinguishable from the weak, immature little girl Bettelheim described. In fact, in this version, it is the wolf who needs saving. The relationship between the two main characters takes the form of a sexual initiation in which Little Red Riding Hood is a conscious player and not a victim of wolfish (male) desire. The girl takes the initiative and tames the wolf with her sexuality and sense of humour.

It has to be said that Carter’s modern approach to fairy tales is fitting. After all, in Bettelheim’s own words, “[a]s with all great art, the fairy tale’s deepest meaning will be different for each person, and different for the same person at various moments in his life.” So let’s read these special stories not only to children, but also to ourselves. Let’s search them for new meanings and guidance. Let’s interpret Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and Gretel and Snow White in accordance with the current needs of the heart. Let us discover in them universal psychological laws. Because, as Bettelheim insisted, it is only when we find our inner authenticity that we can make a change in our lives for the better.