He subjected himself to electric shocks and noted down his experiences. He distinguished between rivers by their flavour. He researched nature with passion, seeing in it a singular powerful force. An uncaring son, a scientist of the Romantic period, whose fame was envied by Napoleon.

Pink flamingos wade in shallow water, yellow and blue crayfish scuttle along the seabed, bizarre red flowers bloom in palm trees, while fish and birds have so many colours that they resemble a rainbow. Nature constantly stimulates our senses, as even at night a meteor shower leaves thousands of white trails in the sky. It is hard to be a stoic surrounded by such scenery. 29-year-old Alexander von Humboldt runs around dazed by the colours. Even his usually calm friend Aimé Bonpland declares that he will lose his mind if these miracles do not end.

Humboldt is finally in his element. He has dreamed about the heat and tropics for a long time. Afflictions of the nervous system and fevers, which he had suffered from in Europe, are easing. He is feeling happier here than ever before. Even an earthquake doesn’t stop him from continuing his observations. He takes electricity measurements, measures the magnitude of the seismic waves, and wonders why they move from the north to the south. Humboldt and Bonpland find so many natural specimens that they are not able to carry them home. They quickly fill their trunks with them. They fast run out of reams of paper, which they use to dry the plants.

On a continent full of wonder, Alexander notes many analogies to the world that he knew earlier in Europe. The trees remind him of Italian pine trees. From the distance, a field of cacti resembles grasses on the swamps of Northern Europe. The caves are the same as in the German Franconia. And a valley is a copy of the English Derbyshire. From his first days in South America, Humboldt has the feeling of “one great whole”.

“Everything seemed somehow interconnected, and this concept was to shape his outlook on the natural world for the rest of his life,” writes Andrea Wulf in Humboldt’s biography The The Invention of Nature.

The dreamer

He is born on 14th September 1769, one month after Napoleon Bonaparte, to a wealthy aristocratic family. Alexander’s father is a chamberlain on the Prussian court, his godfather becomes the future King Frederick William II. Alexander struggles at school, but is interested in nature; he collects shells and plants. Ever since he saw palm trees in the Berlin botanical garden, he has been thinking about touching them in their natural environment. He reads the diaries of James Cook and dreams about travelling. Yet his life is ruled by his mother. She sends her 18-year-old son to Frankfurt (Oder) to study administration. Humboldt cannot stand these studies, as well as his subsequent studies in economics in Hamburg. On the Laba River, he observes ships carrying rice, tobacco and indigo. This sight is the only thing keeping him alive, he confesses to a friend.

He takes more liking to the next school chosen by his mother: the Freiberg Academy of Mining. In the mines, he collects samples and learns about geology. In his free time, he researches the influence of light on plants and collects thousands of botanical specimens. In eight months, he completes the three-year programme of studies and as a 22-year-old he becomes a mining inspector. He travels around Europe professionally, examining soil, mineshafts and ore. After work, he conducts thousands of experiments: he cuts, pierces, punctures frogs, lizards and mice, and subjects them to electric shocks. He cuts his own shoulders and torso with a scalpel, gives himself electric shocks and scrupulously notes down his sensations. He isn’t concerned that many wounds become infected…

In Jena, the centre of the new Romantic thought, he visits his brother Wilhelm. Through him, he meets Goethe, Schiller, and other intellectuals. 20 years his senior, Goethe, equally fascinated with literature as with the origin of the Earth and botany, listens to the 25-year-old Humboldt with amazement: “Eight hours of reading books won’t provide you with as much information as you can get from him in an hour.” They are fascinated with each other. Humboldt believes that getting to know the writer provided him with “new organs”.

Yet Jena is an exception. Prussia makes Alexander feel uncomfortable and restricted. He will experience this until the end of his life. An oppressive mother, oppressive authorities, oppressive ideas. According to the view held in Prussia at the time, nature is to be corrected so that it fits in with the norms set by officials. A wild forest is considered an insult hurled at a human being. The term Normalbaum is the essence of this outlook. It was coined by the 18th-century forester Johann Gottlieb Beckmann, who considered forests to be untidy because the trees growing there are taller and smaller, thicker and thinner; some trees are healthy and others rot; in addition they don’t grow in even rows and lines grouped according to the species. To make the exploitation of forests easier, this mess – claimed Beckmann – needed to be tidied up. Hence he came up with the concept of Normalbaum, a normal tree, an ideal tree, that is worthy of growing in a German forest. Those that are not ‘normal’ need to be removed.

Humboldt’s views are the opposite of the Normalbaum doctrine – as are his temperament and personality. The Romantic, a passionate man, always loyal towards his friends. Some people claim he was homosexual, but it is difficult to be certain about it. In any case, he doesn’t fit ‘normal’ Prussia. No, Humboldt isn’t made to the official Prussian measure. He dreams about the tropics, adventures, of leaving Germany. The rebellion is about to commence.

The turning point comes with the death of his mother in 1796. None of her sons comes to her funeral, and a month later Alexander resigns from his job as a mining inspector. He is finally free! Thanks to the inherited fortune, he begins to realize his dreams: he researches tropical plants in the greenhouses of the imperial gardens in Vienna, and in the Alps he measures the height of mountains and tests meteorological equipment. During storms, he stands in the rain to detect atmospheric electric charge.

In Paris, in the hallway of the tenement where he rents a room, he encounters a young French scientist with a can for botanical specimens. It’s Bonpland, with whom Humboldt will soon plan an expedition. Humboldt has enough money, but due to continuous sea battles, nobody wants to rent him a ship. He strikes lucky in Madrid: the king of Spain, Charles IV, grants him a passport to a colony in South America. As the first foreigner, Humboldt is granted permission to freely research the Spanish territories. In exchange, he has to bring back specimens of flora and fauna for the royal gardens.

He departs from La Coruña in 1799. He intends to prove that “all forces of nature are interlaced and interwoven.” When, during the cruise, he sees the Crux Constellation for the first time, he feels that his dreams are finally coming true. When he steps onto the coast of what is now Venezuela, he immediately takes out a thermometer. He inserts it into the sand and notes down 37.7°C – the first of thousands of measurements.

The ecologist

He conducts experiments with electric eels and becomes seriously injured while doing so. He almost dies while researching curare (he is the first European to describe the activity of this poison). He comes across Brazil nuts, which he will later bring to Europe. He tastes water from various rivers (the Orinoco is particularly repugnant, while the Rio Atabapo is delicious). The trees, on the other hand, cannot be distinguished by the flavour of their bark, as every tree bark tastes the same, he claims – after tasting them.

He creates a map: it is completely different from the already existing maps, which are so imprecise as if “they were invented in Madrid.” He believes that “what speaks to the soul, escapes our measurements.” His biographer Andrea Wulf claims that Humboldt described South America with the eyes he received from Goethe. Nobody had described the world in such a way before. Only Humboldt describes the cataracts of the Orinoco river as “illuminated with the rays of the rising sun”, a fog river as “suspended over its bearing”, while the moon “is surrounded by colourful rings.”

He also has concerns. When he observes the slave market opposite the house he rents in Cumana, he becomes an abolitionist. When he looks at the mass deforestation of trees on the Valencia lake, he realizes that this is the cause of soil degradation and the decrease of water level in the lake. When he sees that in the valley of Aragua, the cultivation of indigofera, which contains blue dye, takes over space for edible plants, he understands that the European’s desire to wear colourful clothing is pushing the residents of South America into poverty. Humboldt is the first to connect colonialism with environmental destruction. He fights against the popular belief that the arrival of colonizers has a salutary influence on the South American climate and that the deforestation of the primaeval forest – a terrible place full of decaying trees and rotting leaves – makes the air healthier and milder. In opposition to the researchers of that era, he claims that: “Man can only act upon nature and appropriate her forces to his use by comprehending her laws.”

What is more, he doesn’t consider the native peoples as barbarians. He speaks, on the other hand, about “the barbarism of civilized man.” After his return to Europe, he will present an unprecedented picture of the people that Europeans largely call ‘savages’. He will also undermine the belief that South America has only just emerged from the ocean and has no previous history. As evidence, he will describe ancient buildings and traces of ancient societies.

Years later, when he will also visit Russia, he will add “the great masses of steam and gas” in industry to the set of destructive human activity. His theses are so controversial and seem so implausible that even Humboldt’s translator includes a footnote in the German edition of a book, which says that the impact of deforestation that the author talks about is dubious.

The inventor

After six months, the scientists move to Cuba. There, Humboldt finds out that Captain Nicolas Baudin is sailing around the world and that he will visit South America on his route. He has no means to contact him, but Alexander is convinced that the ship will stop at Lima. He immediately quits his planned trip to Mexico and decides to go to Peru. He wants to join the expedition. He has time. During his nine-month journey he scrupulously researches the Andes. When he finally reaches Quito, it turns out that Baudin chose a completely different route.

Yet Humboldt is full of zest. He announces that instead of going to Australia, he will research volcanoes. He sets up a base in Quito and for the next five months he climbs several dozen volcanoes. He takes measurements and becomes the most experienced mountaineer in the world. His biggest obsession – according to Wulf – is Chimborazo (6300m above sea level). It was believed back then to be the highest mountain in the world. Humboldt and Bonpland almost reach the top, a height that no human had reached before.

“Looking down Chimborazo’s slopes and the mountain ranges in the distance,” writes Wulf, “everything that Humboldt had seen in the previous years came together. His brother Wilhelm had long believed that Alexander’s mind was made ‘to connect ideas, to detect chains of things.’ […] Humboldt was, a colleague later said, the first to understand that everything was interwoven as with ‘a thousand threads’. This new idea of nature was to change the way people understood the world.” Climbing Chimborazo confirmed that he was right: the plants growing in the Andes are similar to the ones growing in the Alps. Everything is interconnected.

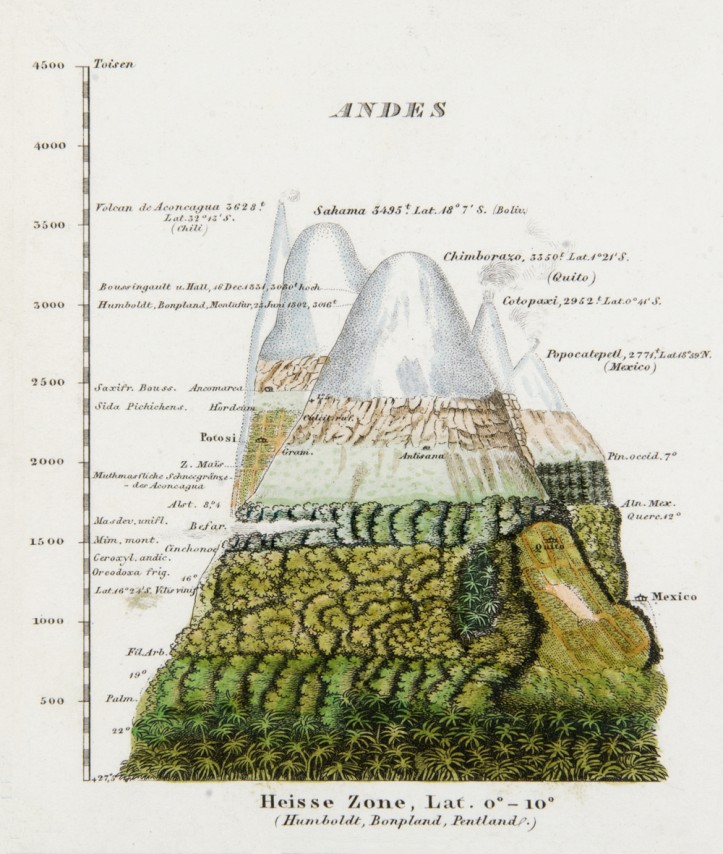

As confirmation, he sketches his Naturgemälde, an illustration of the Chimborazo peak with its flora from the valley to the snow zone. He will later publish it as a 90 x 60 centimetre print. In it, he will show the plant zones that are influenced by temperature and height fluctuations. The print will cause shock in the science world, but it will forever shape the understanding of ecosystems.

This is not the end: in the Peruvian Cajamarca, south of the Equator, Humboldt discovers the magnetic equator of the Earth; on the coast he establishes the reasons for the richness of the sea ecosystem (the Humboldt Current); he also observes the eruption of the Cotopaxi volcano. In February 1803, during a cruise to Acapulco, aged 33, he crosses the Equator for the last time in his life. He spends one year in Mexico. He then travels through Cuba to the United States. He meets President Thomas Jefferson. He passes on his maps to him and gives him information about Louisiana and Mexico; he talks about the world and his discoveries. According to the president, it is the most fruitful and exciting visit he has had in many years.

From the Americas, Humboldt carries dozens of notebooks, hundreds of sketches, thousands of scientific observations, dozens of thousands of plant specimens. In times when European scientists had recognized only 6000 plant species, Humboldt presents them with 2000 new ones. He gives the specimens to other scientists, as he believes that future discoveries demand collaboration. After five years of travelling, he returns to Paris as a hero, just before his 35th birthday.

The visionary

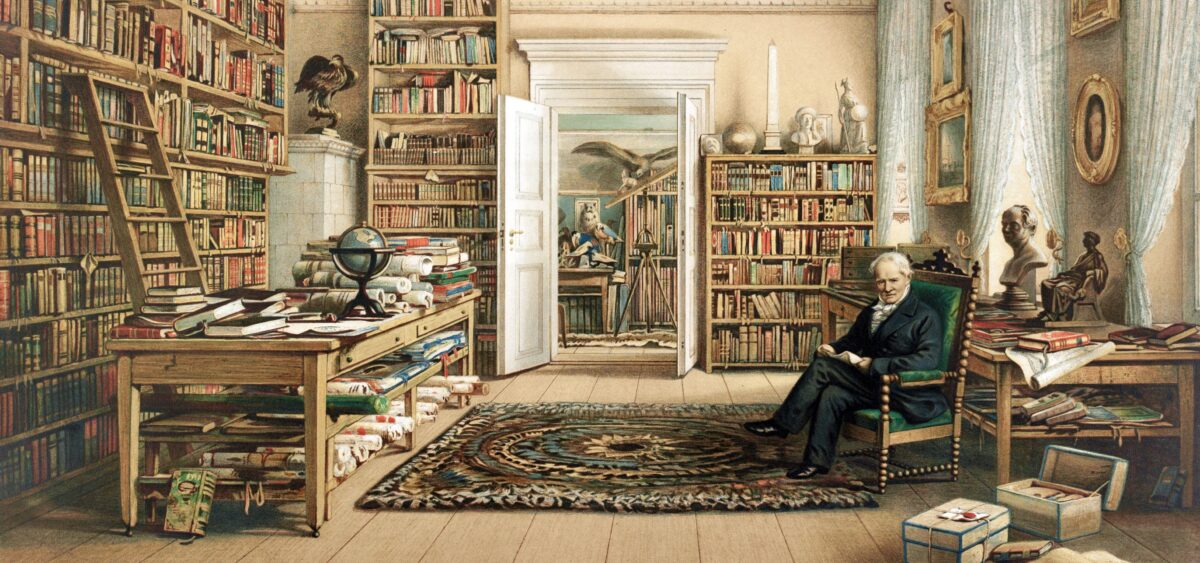

He lives in the capital of France because he believes it is the place in the world most saturated with science. During his expedition, he spent almost all the money inherited from his mother, so reluctantly (because he would rather be independent) he accepts permanent income and the title of chamberlain from the Prussian king, Frederick Wilhelm III. He is so ashamed of it that he asks his acquaintances for discretion.

In his book 200 uczonych w anegdocie [200 Scholars in Anecdotes], Andrzej Kajetan Wróblewski says that at the start of 19th-century, there were no people more famous in the world than Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander Humboldt. The ruler of France is one of the few people who is hostile, possibly out of envy, towards the Prussian scientist. “Oh, you are interested in botany, my wife is also interested in it,” Bonaparte taunts him one time.

Wróblewski also tells another anecdote: in Paris, Humboldt becomes friends with the French chemist and physicist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac. He helps him to research the ratio by volume in gas combinations. To do so, they need glass flasks with very thin walls, which are only made in German glassworks. To deliver them to France, one has to pay high customs duties. Humboldt asks for the containers to be closed and labelled with stickers saying ‘German air’. Such goods are not listed in the registers of the French customs officers who let the delivery through without any additional payment.

According to Wróblewski, Humboldt is the last scientist who grasps the entirety of natural history. He is able to write on any subject – and so he does. He publishes books in entire series, distinct in their genre. Specialist books that expertly talk about fauna, flora or astronomy. Literary books whose beautiful style is combined with descriptions of nature – he doesn’t allow the publisher to make any corrections, because “the melody of the sentences would be destroyed.” Books that are graphically enticing, full of spectacular etchings showing mountain tops, volcanoes, Aztec manuscripts, Mexican calendars. And for the mass reader, books on popular science as well as lively-written, adventurous accounts of travels through tropical forests, the Llanos savanna, or the noisy streets of Latin American cities. They arouse such emotions that, according to the Edinburgh Review: “[…] one is exposed to danger along with him, sharing fears, successes and disappointments.”

When he doesn’t write, Humboldt loves telling stories. Not everyone follows his storytelling, and someone points out that his words constitute his loud thinking. He thinks in a multifaceted way; it happens that he cannot catch up with his own thoughts. Some of his ideas will need to wait many years to be realized.

The first of 34 volumes of Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent is the first book on ecology in the world. The essay about plant geography includes the Naturgemälde, with an explanation of a completely new view on flora. In it, Humboldt compares coniferous trees in Canada with the trees growing at high altitudes in Mexico, oak trees and pines in the Andes with the trees in the countries of the Northern hemisphere, and moss from the banks of the Rio Magdalena with the moss in Norway. He connects flora, climate and geography, in a way that nobody else has. He reaches a surprising conclusion that at the same latitude identical temperatures do not occur, contrary to what everyone believes. He claims that temperature is affected by altitude, the continent, winds, and the proximity to oceans. He invents isothermal lines that connect points of the same temperature. 150 years before the confirmation of the plate tectonics theory, he believes that Africa and South America once used to be connected. As claimed by his biographer, he provides “Western science with new lenses to observe the natural world.” Stunned with the Naturgemälde etching, Goethe puts it up on his wall and cannot stop looking at it. He praises Humboldt, saying that he lit science into “a bright flame” with “an aesthetic breeze”.

The capital of France is only slightly warmer than Prussia. Missing the tropics, Humboldt sits in an overheated office, while his guests, dripping with sweat, put up with horrible temperatures out of politeness. For a decade he tries to get permission to go to India. He wants to conduct research in the Himalayas and compare them to the Andes. He now needs analogous permission from the East India Company, which he had previously received from the Spanish king to explore South America. Yet the Brits know him too well. They have heard his opinions about the cruelty of Europeans. They would be naïve to let a fierce critic of colonialism onto their territory.

In addition, Frederick Wilhelm III has asked Humboldt to return to Berlin more than 20 years after his return from his expedition. As one of 250 chamberlains, he is to “entertain the King intellectually and read to him after lunch.” Grounded in Berlin, Humboldt takes the opportunity to give lectures about the world. He doesn’t take any money for it, so along with Frederick Wilhelm III and the members of the royal family, his lectures are also attended by workers, while half of the audience constitute women. On the days of his performance, the streets get jammed. There are so many people wanting to attend that his lectures need to be organized in a concert hall. Some people make mean comments about the room being too small for the audience, while the audience’s heads are too small for the lectures. Someone else adds that, following the lecture, one of the female attendees wanted to order a dress with sleeves the length of two Siriuses. Humboldt isn’t bothered by the comments. “The most important thing is that ladies have been coming at all,” he replies.

He is no longer a lively young man, his right shoulder is paralysed by rheumatism, and his hair is grey. While wiping away tears that he will no longer see the Himalayas, he receives an offer from Russia to research gold and platinum deposits in the Ural Mountains. In 1829, at the age of almost 60, after a 25-year break, he sets off on another big journey. He thinks of analogies again and contrary to all, he claims that since in Brazil diamonds can be found in gold and platinum deposits, they can also be found in Russia. “A mad Prussian prince,” members of the expedition laugh at him. Nobody had ever found diamonds beyond the tropics. When it turns out that Humboldt was right, they accuse him of using magic.

To make his biggest dream come true – to complete the Naturgemälde – in spite of the agreement with the Russians, he travels further east, all the way to the Altai Mountains. He makes observations and takes measurements, depending on the sense of amazement. The analysis is equal to his emotions and impressions. When others look for universal laws, Humboldt claims that nature needs to be researched with emotions. He has the innate gift of a memory for details. In his mind, he keeps the shape of a leaf, the colour of a rock or the temperature; years later, he compares his observations from places thousands of kilometres apart.

When he stands on the borderline between the steppe and the Altai foreland, he estimates that he is 5600 kilometres east of Berlin, exactly the same distance as between the capital of Prussia and, to its west, Caracas. Everything is interconnected – he is certain of it by the time he has reached the Altai Mountains. Nature is a homogeneous force and different continents have analogous climate zones. On his way back, carrying specimens of plants, rocks and hundreds of measurements in the trunks, he visits (again illegally) the Caspian Sea. It is the last expedition in Humboldt’s life.

Following his return and thanks to his initiative, countries in the world join forces and found magnetic stations. Thanks to the so-called magnetic crusade, within three years, almost two million measurements are conducted.

The student

Over a period of 10 years, he writes his most monumental work (which he will publish at the age of 75). Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe is a summary of the sky and the Earth, “a living whole”, as Humboldt puts it. When the world divides science into smaller disciplines, he brings them all together in one book. To prepare it, he engages with scientists, philologists, historians, astronomers, geologists and travellers who send him data about plants from around the world. “He had a cosmic perspective and they constituted tools in his great plan,” claims his biographer. He never has enough of gaining knowledge. Even in his old age he sits between students of the University of Berlin, listening carefully and busily taking notes. When he doesn’t turn up at university, the students laugh saying that “Alexander has skipped today’s lecture because he is having tea with the King.” The German publisher of Cosmos says that he has never received so many book orders, even when publishing Goethe’s Faust.

Humboldt doesn’t stop working. The second volume is a journey from ancient civilizations to modernity. He writes even more books. Despite many translations into other languages, there is no income from them, as copyright doesn’t exist at the time. Humboldt’s books make an impression on Pushkin. They are read by Darwin, who during his journey on the Beagle ship notes down whole excerpts in his diary. The books inspire Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and other scientists and travellers.

Humboldt’s books are studied by Simón Bolívar, who wants to get to know the continent and liberate it. He claims that these books, which praise South America and criticize colonialism and slavery, “have taken me out with the roots”, and with his pen Humboldt has woken South America up and contributed to its liberation. According to his biographer, Humboldt’s surname is more widely known in South America than in Europe or the United States. Wulf also claims that there has been no other man whose surname would be given to more objects, phenomena, places, and species. Let’s mention only some of them: an ocean current flowing along Chile and Peru; a city in Argentina; a river in Brazil; a geyser in Ecuador; a bay in Colombia; mountains and mountain tops in the whole of Latin America; Cape Humboldt and Humboldt Glacier in Greenland; mountain ranges in China, Africa, New Zealand and Antarctica; rivers and waterfalls in Tasmania and New Zealand; streets and parks in Europe; counties, cities, mountains, bays and rivers in North America.

In his honour, his name was also given to a South American penguin, a two-metre long squid, a Californian lily, to almost 300 other plants and over 100 animals, and also to minerals and a plain on the Moon called Mare Humboldtianum. His name was also given to so many ships that scientists called them his “sea power”. The researcher’s portrait was exhibited in the Great Exhibition in London and in the palace of the King of Siam, while in Hong Kong people celebrated his birthday. In German-language schools in Latin America, the Humboldt sports Olympics take place every two years. The American state of Nevada was also close to being named after Humboldt.

The inspirer

When in February 1857 his servant finds him on the floor after a mild stroke, the 88-year-old scientist doesn’t waste time and writes down his symptoms (temporary paralysis, unchanged pulse). Almost one month after submitting the fifth volume of Cosmos, Humboldt dies at the age of 89. As a farewell he says: “How grand these [sun] rays! They seem to beckon earth to heaven.” The same day, on 6th May 1859, unaware of the death of his idol, Darwin writes to his publisher, promising that he will soon send the first six chapters of On the Origin of the Species. The world will be shaken by the theory of evolution. All owing to Humboldt. “Darwin stood on Humboldt’s shoulders,” Wulf believes.

Not only Darwin. The whole modern understanding of the world comes from Humboldt. Goethe claims that Humboldt is “like a fountain with many pipes, under which you need only hold a vessel, and from which refreshing and inexhaustible streams are ever flowing.” Andrzej Wróblewski quotes one more anecdote: someone spreads a rumour about the scientist’s death. A naturalist dreams of measuring Humboldt’s skull.

“Unfortunately, I cannot give you my skull,” Humboldt writes in a letter to the naturalist, “because I will still need it for some time. It will be available at your disposal in the future.”