Meet Pando, Pando is great. He looks like a forest, but is actually one organism. All his tree trunks have the same DNA, and grow from a single root system.

The American aspen (not to be confused with European aspen) often forms such clonal colonies, but Pando, a male specimen growing in Utah, a mile from the shore of Fish Lake, is a unique life form. It’s made up of 47,000 trees, covers an area of almost forty-four hectares, and weighs 6,500 tons with its roots. In a nutshell, it’s huge.

Its discoverer, Burton Barnes, believed that this giant could be up to a million years old. Currently, it’s thought to be younger, that is around eighty thousand or—according to the most guarded estimates—fourteen thousand years old. Either way, it’s much older than any single living tree.

But is it old, and has Pando been growing for thousands of years without changing? When one of the trunks dies, it triggers a chemical reaction in the root system, causing a young shoot to spring up nearby. And so, generation after generation, Pando died and was progressively reborn, again and again.

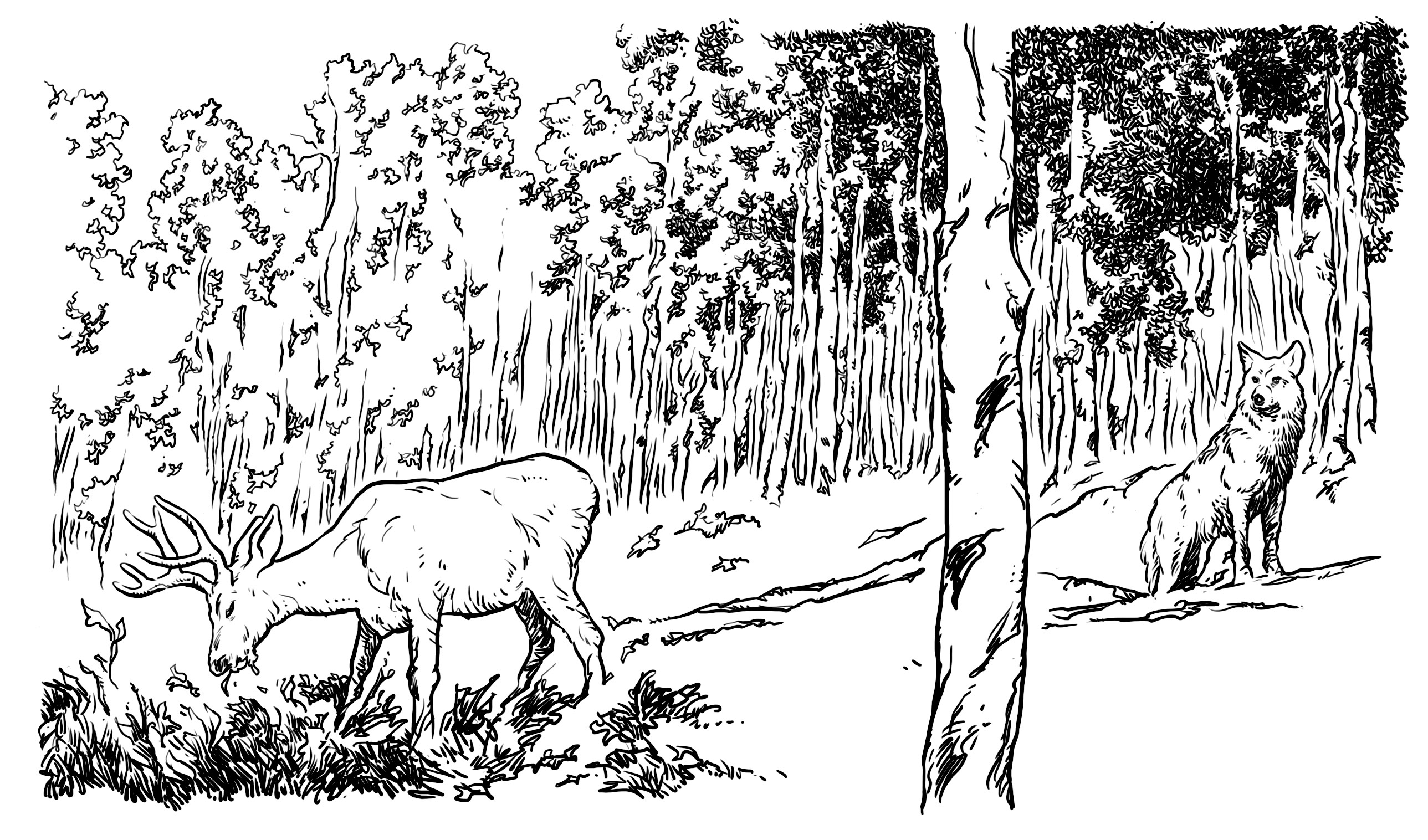

However, all this ended when the wolves vanished. Of course, they didn’t disappear by themselves, people wiped them out, either from fear, or perhaps jealousy. With the wolves gone, the mule deer, native to the land, were no longer afraid, roaming undaunted, and searching the ground cover for their favorite morsels. And it turns out that their favorite snacks are aspen root sprouts.

Presently, the “forest” consists of dead horizontal tree trunks and large vertical trees, but these are nearly 120 years old. They are nearing their end, and there are no young trees to replace them.

That’s why fencing the area is being trialed. However, aspen shoots must be exceptionally irresistible for the deer, because, as it turns out, an almost eight-foot high fence is not enough of an obstacle for them. Besides, partitioning anything in nature is rarely a good idea.

The simplest thing to do would be to bring back the wolves, not to stamp out the deer but to awaken their vigilance and mobility, as well as make them less picky in their culinary tastes. A similar solution has been implemented at Yellowstone National Park, saving its ecosystem.

No amount of culling can replace a natural predator, no gamekeeper can replace a wolf. It’s hard to say whether local and summer residents of Fish Lake would agree to such a solution—to either save the great Pando, or let it die after thousands of years.

Translated from the Polish by Maciej Mahler