Thousands of Londoners died because of smog. But at first the authorities tried to pin the blame on viruses!

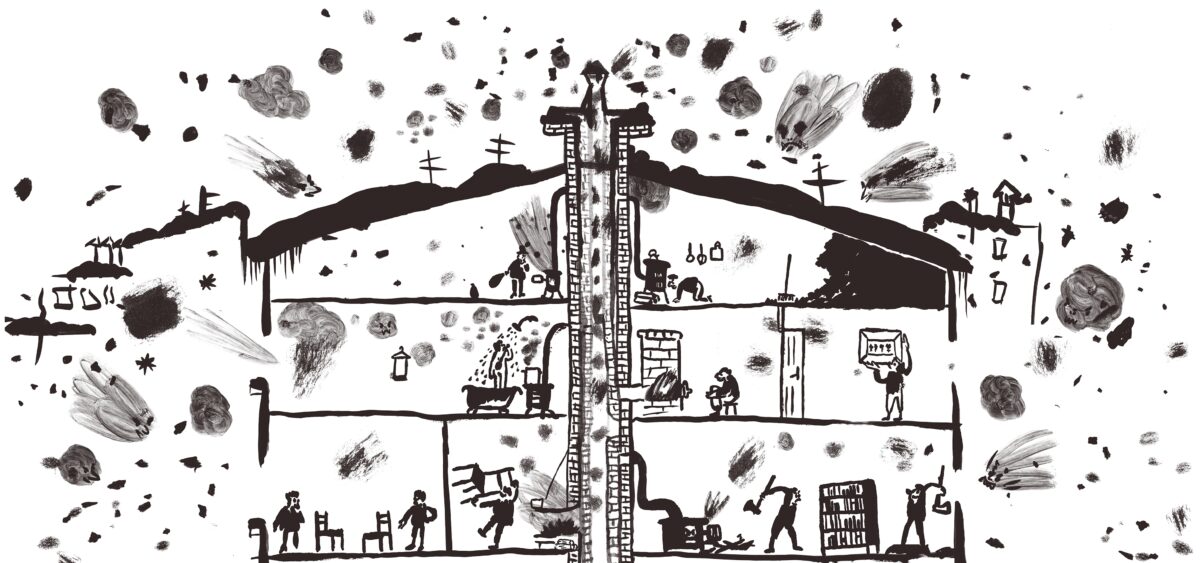

On 5th December 1952, the average resident of London had to rub their eyes in disbelief. Yes, they were used to the proverbial London fog. And they knew what smog was; as early as the 19th century dirty clouds of it had been described, so thick and yellow that Londoners compared it to pea soup. It stank of gas from pipes, odours from docks and shipyards, smoke from factories, fumes from paint factories, breweries, laundries and bakeries. But even knowing all of this, they could still be shocked. What was happening exceeded human comprehension. In the nasty yellowish clouds, London’s bridges disappeared, along with Nelson’s Column and Big Ben. The smog got into buildings. Even into cinemas, where screenings were called off because the audience couldn’t see the screen.

With visibility at the airports limited to a few metres, flights were cancelled, as was shipping on the Thames. Trains crawled at a snail’s pace. Ambulances couldn’t reach the ill in a city of nine million; those in need had to make it to hospital on their own. The most sure means of transport was the Underground. Pedestrians, barely able to catch their breath in the stinking smoke, lost their way and risked being struck by straying cars. Police officers carried flaming torches into the streets to penetrate the clouds of polluted air and get control of the mess.

And that was just the start of the real Armageddon.

Bacteria or chimneys?

For five apocalyptic days, from the 5th to the 9th December, London was drowning in smog, and hospitals could barely cope with the inflow of patients. Almost 200,000 people required hospitalization! Some couldn’t be helped anymore. There were so many deaths that mortuaries started running out of coffins. The British, after the recent World War II, were used to challenges and dangers. Even so, the scale of the event started to disturb them.

Meanwhile, the authorities were hiding their heads in the sand. And even worse – they started to cover up the truth. The Ministry of Health told Britons that they were reaping the harvest of epidemics of influenza, bronchitis, pneumonia… In fact, the fault lay not with viruses or bacteria, but furnaces and chimneys! Coal was burned in thousands of London homes and factories – low-quality coal, because the better fuel was exported. At the start of December, the temperature in London fell to a few degrees above zero, so the furnaces started to work – and pollute – harder. What’s more, because of differences in pressure, a layer of cold air spread out over the ground, squeezed down by warmer air (though it should be the other way around). And because of this stubborn cold, even more of that lousy coal went into the furnaces!

Along with the smoke from the chimneys and fireplaces, masses of hydrogen chloride and fluroine compounds were pumped into the atmosphere, and worst of all, 370 tonnes of sulphur dioxide. Breathing in this toxic compound damaged Londoners’ lungs. Fortunately, after a few days the wind finally came, breaking up the deadly yellow clouds.

The truth about these events broke through slowly. When the authorities acknowledged the real cause of the deaths, they estimated that as a result of respiratory failure and insufficient oxygen, 4000 Londoners had died in just a few days. But when in the 21st century researchers looked at the data from 1952, they said there may have been three times as many victims – around 12,000.

Egyptian pollution

Although the British authorities manipulated uncomfortable facts, they started to act quite quickly to ensure the tragedy wasn’t repeated. In 1956, they passed the Clean Air Act. They created zones in cities free from harmful fumes, ordered residents and factories to switch to smokeless fuels, and promoted gas and electric heating.

Even so, 10 years after the drama of 1952 the situation recurred, though on a much smaller scale. More regulations were passed, and then more yet again. Further monitoring of the situation and introduction of new technologies led to progress, but as late as 2007 it was estimated that every year, pollution caused the untimely death of 1000 Londoners, and another thousand went to hospital.

Today London is still more polluted than capitals such as Oslo, Helsinki, Stockholm, Madrid, Dublin and even Washington. The top spots in the global ranking go to cities in India, China, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. In the EU, the leaders in this ranking of shame are two cities in Bulgaria (Vidin and Dimitrovgrad), but in the top 20, alongside five Bulgarian cities, there are as many as 15 Polish ones! Starting with Opoczno, through Żywiec, Rybnik, Pszczyna, Kraków, Nowa Ruda, Nowy Sącz…

Scientific research indicates that air pollution causes the death of about 50,000 Poles each year. The losses it causes reach as high as 80 billion złotys (ca. £16 million). To prevent this, we would need first of all to replace or modernize furnaces and use the right fuel in them. Because Poles have regulations that they just don’t follow.

But some could say – also citing scientists – that there’s no civilization without environmental degradation. Even the ancient Egyptians died from atherosclerosis, which was contributed to by the air pollution of the day. While they lived in a pre-industrial society, they still cooked and baked, worked in mines and quarries, in dust and sandstorms. They lived in spaces where something was always smoking. Examinations of mummies leave no doubt that all of this harmed even the higher social classes, not only simple workers and artisans. Egyptian pollution was even worse than the plague of darkness known from the Bible!

The stubborn will say that the problems of Kraków or London with smog are still nothing in comparison to the threat in places like China. But that’s no justification. And it’s hard to ignore that even children joke that the famous dragon (smok) of Kraków is actually smog.