In India, the British mindlessly provoke a rebellion uniting the Muslims and Hindus against them. And all because of… fat.

Mangal Pandey was a sepoy – an Indian soldier in the 34th Bengal Native Infantry regiment of the British East India Company. A soldier, like any other. There had been unrest in his company at Barrackpore for several weeks. The British had just introduced the Enfield rifle into service, which had aroused protests from the sepoys. The powder and shot for this weapon came in paper cartridges that had to be bitten before use. The problem was that in order to protect the powder from damp, the paper was soaked in pork or beef fat. For the sepoys, this was a violation of a religious taboo. Those who followed Islam didn’t want to touch pork fat. In turn, those who were Hindu could not countenance using fat from sacred cows.

However, the British remained deaf to their protests. They also brought reinforcements of soldiers from Europe. Mangal Pandey learnt about this on the afternoon of 29th March 1857. He was cleaning his rifle at the time. He was overwhelmed by anger and fear. He was also pumped up on a local preparation of cannabis, known as bhang. He claimed that waiting any longer would only make the situation worse. He grabbed his rifle and sword and ran out onto the parade ground.

A one-man rebellion

Pandey called out to his comrades. “Come out – the Europeans are here! From biting these cartridges, we shall become infidels!” he exhorted them. “Ready yourselves!” However, the remaining sepoys emerged slowly from the barracks without much enthusiasm. “Why are you not preparing? After all this is about your religion!” shouted Pandey, waving his weapon.

At that moment, the British officer J.T. Hewson appeared on the scene, flustered. Without thinking much about it, the sepoy fired at him, but missed. Sensibly, Hewson decided to wait for backup in order to overpower the attacker. Then another British officer by the name of Baugh rode up. “Where is he?” he called, looking about for the rebel. Hewson tried to warn his colleague that he was within range of Pandey, but he was too slow. The sepoy fired.

The bullet hit Baugh’s horse, and it crashed to the ground together with its rider. Amazingly, Baugh managed to extricate himself quickly and charged towards Pandey with his sword and pistol raised. Hewson ran after him. Taking advantage of the fact that the sepoy was reloading his rifle, Baugh fired at his opponent. However, he missed and then threw his now useless gun at the Hindu. Hewson attacked the sepoy with his sword. The Hindu parried his thrust with his rifle; so powerfully that the officer’s sword cracked at the hilt! Pandey then set about the British with his own sword. He slashed from left to right, injuring Baugh in the arm and Hewson in the head.

Other sepoys were already running in. The question was, which side would they join? Many tried to protect their rebellious comrade with their weapons. Others stayed on the side of the officers. Meanwhile British soldiers arrived with their weapons loaded and ready to fire. Pandey still tried to defend himself, but in the end, in desperation, he turned his weapon on himself. He pressed the barrel of the rifle to his chest and pulled the trigger with his toe.

The spark that set India alight

He survived his suicide attempt. They patched him up in hospital and then – what else? – put the 29-year-old on trial. The British sentenced him to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on 21st April the same year. The rebel unit was dissolved.

However, the British were unable to stop the growing rebellion. On 10th May, it erupted with full force in the garrison at Meerut. This was the start of the so-called Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Mutiny). The colonial army in India at the time consisted of 45,000 British soldiers and 230,000 locals. Within 100 days, 90% of the latter had joined the rebellion. The mutineers objected to British domination and, more particularly, the religious proselytization carried out in India by Christians from Europe. Both Muslims and Hindus feared losing their identities. As their leader, they chose the venerable Bahadur Shah II, a descendant of the dynasty of the Great Moghuls.

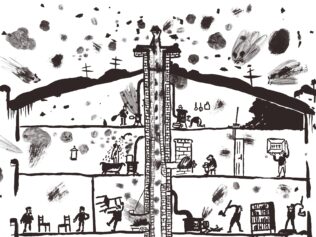

He was not known for being a fanatic, but the sepoys fought exceptionally ferociously and brutally. First, they went for the British officers; their superiors. Then they went after the ordinary soldiers sent to fight them. Finally, they started to slaughter civilians. The Muslims in India declared jihad, a holy war, against the British. And the British repaid them in kind. They murdered and plundered. They killed prisoners by tying them to the barrels of their cannons. These macabre executions were recorded in illustrations in British magazines and books. In order to quell the rebellion, the British brought in Sikhs, Ghurkhas and Punjabis. They caught and imprisoned Bahadur Shah II and murdered his male descendants in a dark alley in Delhi. After several months, the rebellion collapsed.

A ticking timebomb

The sepoys lost, but the rebellion led to certain fundamental changes. Above all, the British liquidated the famous East India Company, a corporation that treated the Indian subcontinent like its personal fiefdom. From then on, a Viceroy would rule India instead – that is, a governor reporting directly to the British Queen. Nevertheless, the fate of the inhabitants was still miserable. Mike Davis, in his book Late Victorian Holocausts (2001), estimates that in the last decades of the 19th century, through London’s robbery and inhumane policies, 12 to 29 million people died of hunger in India!

Another result of the Indian Mutiny was that the number of forces made up of Hindus was limited, and more British soldiers were sent to the colony together with their families. This created a distinct Anglo-Indian culture where certain aspects, such as afternoon tea, gin, and cricket, still survive on the sub-continent today, having become symbols of a certain cultural elegance.

Finally, the mutiny sparked the Hindus’ aspiration for freedom. This came to fruition in the 20th century with a successful political fight, and even without having to resort to violence. Thanks to this, in 1947, 90 years after the Sepoy Mutiny, India gained her independence.