It’s the end of 1939. Six-year-old Helena is living in the Praga district of Warsaw, next to the orangeade and beer factory owned by her dad. His best, most-trusted employee is a man called Kamil. There are three religious buildings nearby: a Catholic church, a synagogue and an Orthodox church. Helena thinks that Praga is protected by three Gods. Time will reveal how wrong she was. An excerpt from the book Kotka Brygidy [Brygida’s Cat], whose author, Joanna Rudniańska, has won the International Janusz Korczak Prize.

But the war changed Kamil most of all. The war turned Kamil into a Jew.

One morning, Helena saw Kamil through her bedroom window. He was walking towards the factory. In the middle of the courtyard, he stopped and looked around him, like someone who has suddenly found themselves in an unfamiliar place. And then Helena noticed the white armband on the sleeve of his brown overcoat. There was something on the armband, some kind of symbol or inscription, but Helena couldn’t see what it was.

She got dressed and went down to the kitchen for breakfast. Mum was sitting at the table, and she was smoking. That was strange too, because Mum never smoked in the morning. Stańcia was standing over the stove.

“Kamil has an armband on his sleeve,” said Helena. “Have you seen it, Mum?”

“You didn’t say ‘good morning’, Helena. And you shouldn’t pay attention to Kamil’s armband. It doesn’t mean anything,” Mum replied. “It’s just a piece of material, nothing more.”

“They’ve issued an order for them to wear armbands. They wanted them to be visible. They can’t even recognize them,” said Stańcia, putting the kettle on the stove.

“Sit down, Helena. Stańcia will get you some porridge. No talking at the table,” said Mum, interrupting Stańcia’s chatter.

Helena knew who Stańcia meant by ‘they’. Stańcia always spoke that way about the Germans. So it was the Germans who’d made Kamil put the armband on his sleeve. But why?

After breakfast, Helena took her skipping rope and went downstairs. She skipped all the way to the doors of their building, then further, to the main courtyard surrounded on all sides by high walls. Some children were playing by the dustbins. In another doorway stood Tomek, the son of Helena’s doctor, Doctor Kosowski. Tomek was already at secondary school, but he liked talking to Helena. And before the holidays he’d gone to Helena’s dad to ask for her hand in marriage.

“When she grows up, I’ll marry her,” he’d said.

“And have you spoken to Helena about this?” asked her dad.

“Helena? She’s just a little rug rat,” said Tomek, indignant.

“So wait until she’s grown up,” her dad said.

Then everyone laughed and called her ‘rug rat’.

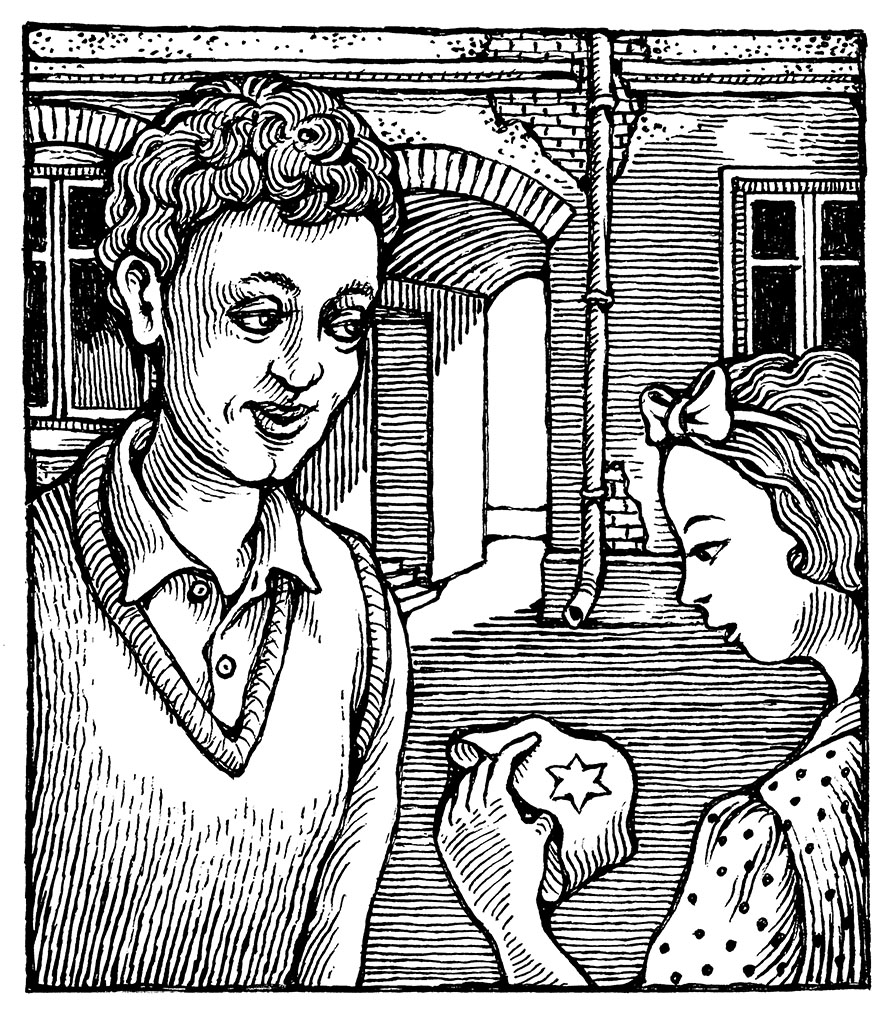

Now Tomek was standing behind the door to the stairwell and watching the boys who were crouching on the pavement playing jacks. He had a white armband on the sleeve of his jacket.

“Oh, you’ve got an armband too,” said Helena. “Where did you get it from, the Germans? They ordered you to wear it, right? That’s what Stańcia said.”

“That Stańcia of yours is stupid. No one ordered me to wear it. It’s a magical armband. Whoever wears it sees what other people can’t see. Only a few people can wear armbands. See, it’s a magic omen.”

There was a blue star on the white armband.

“Aah!”

“Put it on. You’ll see for yourself.”

“Are you giving it to me?”

“I am. But you’ll have to marry me when you grow up. This can only be given to a wife. So, will you?”

“But why do you want me to marry you?”

“Because,” said Tomek, “you’ll be pretty. Because your mum is very pretty.”

Tomek was a handsome boy with dark hair and blue eyes. He was the head of the street; he kept the biggest roughnecks in line. It would be nice to have a husband like that, Helena thought. But she was only six, after all. What if she liked another boy more? But she so wanted to have that magical armband!

“I won’t be like Mum at all. I take after my dad,” said Helena. “But if that’s what you want, then I’ll marry you.”

“Okay, here you go then,” said Tomek.

He took off the armband and put it on the sleeve of Helena’s navy-blue coat. The armband was too big. Tomek fastened it with a safety pin at the front.

“Well, what do you think?” he asked.

“It goes with my coat. Kamil has one too,” replied Helena, but Tomek wasn’t listening to her anymore. He was looking at the boys playing jacks. He smiled and walked towards them. When they saw him, the boys stood up. He greeted them like an adult, shaking hands with each of them. Then everyone squatted down, and they resumed their game. Helena envied them a bit. She’d like to play jacks too. She looked at her hands. They were much too small for the heavy jacks.

What will I see that others can’t see, Helena wondered, skipping with her rope. But she couldn’t imagine anything, so she skipped back and forth, from doorway to doorway, courtyard to courtyard. What will it be, she thought, looking around her so as not to miss anything. Mrs Szewczykowa, Stańcia’s friend, was crossing the courtyard. She looked at Helena and kept on walking, without even saying “hello”. Then the caretaker, Genio, came out into the courtyard with his broom, and he swept at Helena as if she were a piece of rubbish to be cleaned away. Helena sprung back, thinking it was some kind of joke, but Genio wasn’t even smiling. Then some other neighbours came by, and they passed Helena without a word, looking at her as if she were a stranger. Their eyes are completely different than they used to be, noticed Helena. Maybe they’re looking at me like that because of the armband on my sleeve, she thought. Or maybe I’m seeing them differently, I’m seeing what I couldn’t see before, maybe this is what I was meant to see. Helena felt disappointed. She hadn’t expected to only see mean, hard faces and unfriendly eyes with her magical armband.

And suddenly she saw Kamil. He was standing under the mulberry tree, smoking a cigarette.

“What are you doing, Helena? Where did you get that armband?” asked Kamil, sternly.

He crouched down and looked Helena straight in the eyes, inhaling from his cigarette.

“You’ve got an armband too,” said Helena.

“I’m a Jew.”

“You’re a Jew? Like Mr Istman? I didn’t know you were a Jew.”

“I didn’t know I was a Jew either. I never thought about it, honestly. But you’re certainly not a Jew, Helena. And you’re only six. Where did you get that armband?”

“Someone gave it to me,” said Helena.

“Who gave you the armband?”

“A boy. I can’t say. It’s a magical armband.”

“You’d better take it off before your parents see it. It’s not a magical armband. All Jews over the age of twelve have to wear an armband like this, by order of the Germans. It isn’t a game, Helena. It’s my sister Brygida’s birthday today, she’s twelve. And what did she get for her birthday? An armband with the Star of David!”

“She only got an armband for her birthday?” Helena was surprised. “That’s not much at all.”

“It’s a lot. It’s too much,” said Kamil.

Kamil’s eyes filled with tears. Helena could see them clearly behind the lenses of his glasses. She felt terribly sorry.

“Don’t worry. After all, it’s just a piece of material, that armband,” she said, repeating her mum’s words.

“You’re right, Helena. You’re right. But you’ll take it off, won’t you?”

“Okay. I will,” promised Helena.

Kamil stubbed out his cigarette in the sand and stood up. He turned and walked towards the factory, placing his feet carefully and thoughtfully, as if he were walking a tightrope.

Helena undid the safety pin and removed the armband from her sleeve. She put it in her pocket. And just then, Stańcia ran out into the courtyard.

“Helena! Helena! Lunch!” called Stańcia.

“I’m not deaf,” said Helena, and home she went.

The next day, when Helena went down to breakfast, her dad was sitting at the kitchen table. Helena hadn’t seen him for a few days, because he’d been away on business. She ran over and put her arms around his neck. She sat on his knee and took the fork out of his hand to try some scrambled eggs from his plate.

“Oh, you little magpie,” said her dad, and he burst out laughing.

“Will you look at that, what a child!” said Stańcia, who was standing over the stove. “Yesterday she was skipping around the courtyard all day with a Jewish armband on her sleeve. Mrs Szewczykowa told me, she saw it with her own eyes. The whole courtyard saw, what a disgrace.”

“That’s what I wanted to talk to you about, Helena,” said her dad, seriously.

Helena lowered her head. The smell of the scrambled eggs was making her feel sick. She was scared that she was about to throw up.

“Kamil told me everything. You know, Helena, I’m so ashamed. You’re only six years old, and I… It was very noble of you. I thought about doing it too, putting on that armband with the star… But you know, I didn’t think it would do any good. But today, when I heard that Mr Kosowski had committed suicide…”

“Good thing you didn’t put that armband on, sir. Can you imagine!” said Stańcia.

“Doctor Kosowski? Tomek’s dad?” asked Helena.

“No, Mr Kosowski senior, Tomek’s grandfather,” explained her dad.

Helena remembered the old man with the walking stick who would sometimes go out for a walk with Tomek. Then she remembered Stańcia’s stories about suicides.

“Did he jump off a bridge into the Vistula?” she asked.

“No, no! After all, he was an officer. He shot himself in the head,” said Stańcia snappily, and she ran out of the kitchen, startled by her own words.

“My God, he was an exile too, like me. We were in Siberia together. If only I’d put on that armband and gone to see him, if I’d…”

Her dad stopped talking and silence fell. Helena turned around. Her dad was crying, tears were running down his cheeks. First Kamil, and now him. Why were grown men crying?

“Don’t cry, Daddy,” she said. “Why are you crying? You’re an adult.”

“I’m old, Helena. I can’t take this war. I can’t take it anymore. But you are brave and wise, Helena. You wore the Star of David with pride, all day long. If only everyone… No, it’s impossible, in this country… You’re noble – yes, Helena, you’re noble.”

“Noble? I thought only knights could be noble.”

“You’re as noble as a knight, Helena.”

“Which knight?”

“I don’t know. Don Quixote, maybe.”

Helena remembered the terribly thin knight from the cover of the book. He looked ill.

“I always wanted to be King Arthur’s knight,” she said quietly.

“Lancelot?”

“Lancelot.”

Suddenly, her dad brightened up. He stopped crying. He hugged Helena and squeezed her tight.

“You are as noble as Lancelot, Helena,” he said solemnly.

“So should I always wear that armband?” asked Helena.

“Always? No, no, don’t put it on again,” said her dad. “It’s better not to.”

She saw Tomek a few days later. He was walking along, solemn, wearing dark clothes.

“Oh, it’s my fiancée with her skipping rope,” he said.

“Should I give you back your armband?” asked Helena.

“But I gave it to you. Instead of an engagement ring,” he said, laughing.

“So don’t you want it?”

“No, I have no intention of wearing it.”

“I heard about your grandfather,” said Helena. “He shot himself.”

“He was right to. He was awfully old. I’ll shoot myself, too. Someday, when I’m old.”

“Did he shoot himself because he didn’t want to wear an armband?” asked Helena.

“Perhaps. After all, he was a Polish officer. No one can order an officer to wear some armband.”

“Was your grandfather nice?”

“I don’t know. I never spoke to him. He was completely deaf.”

“Ah,” said Helena.

“It’s a good thing he was deaf. It was a dreadful bang. I actually woke up when he fired. But he wouldn’t have heard a thing.”

“Did you see him afterwards?”

“No, my dad wouldn’t let me go into his office.”

“Shame,” said Helena.

She felt as if it were her grandfather who’d shot himself.

“It really is a shame,” said Tomek, and he walked away.

Translated by Kate Webster