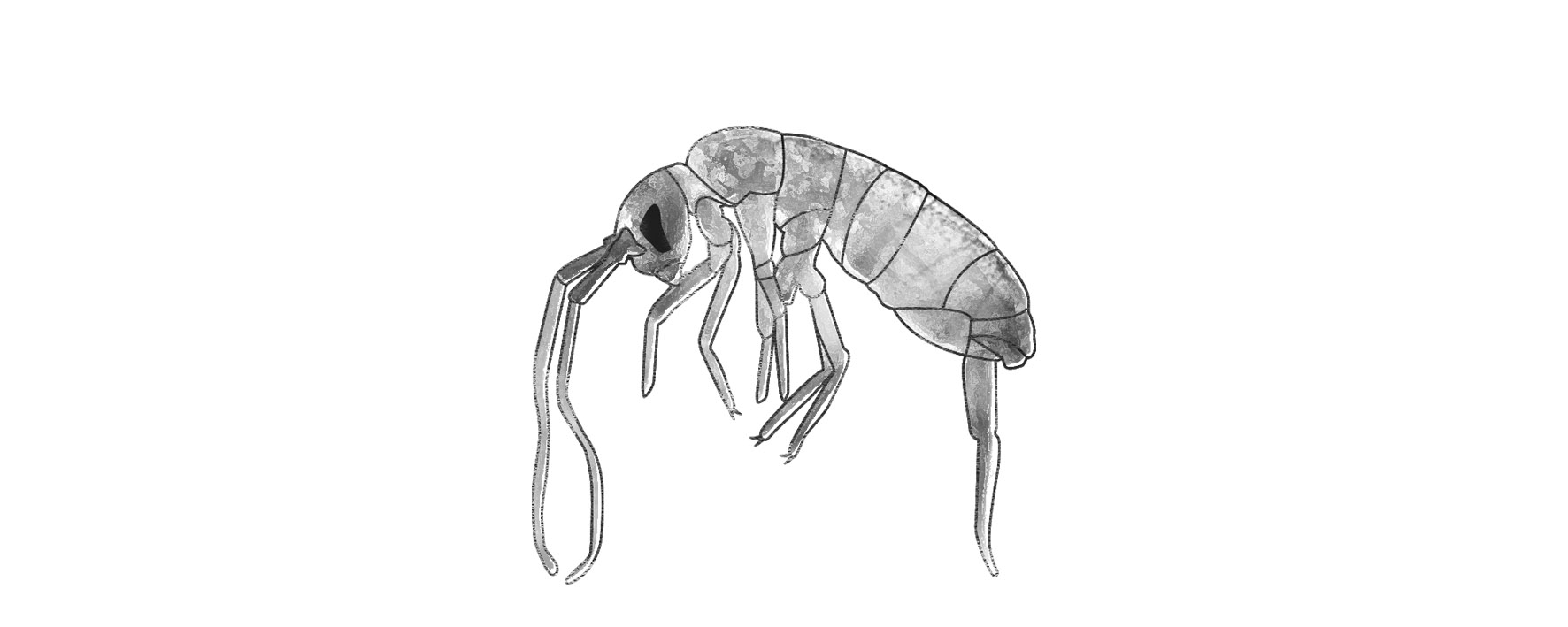

People usually treat springtails as pests. But not Professor Tamura, who studies these tiny creatures and is prepared to do anything to save them. Absolutely anything…

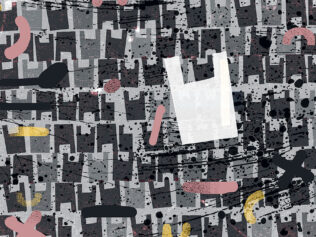

This is a true story. It was told to me by my friends, the Tamuras, who live in Japan, on the island of Honshu, in Iwate Prefecture, in a small house in the countryside. Mrs Tamura translates Polish books into Japanese, and her husband, Professor Tamura, is a scientist who studies springtails – creatures so small that we don’t usually notice them. Springtails live in the soil, in forests, parks and fields, as well as deep underground; they can be found everywhere, even in Antarctica. And there are a lot of them: several hundred thousand can reside in one square metre. Hence Professor Tamura never had any trouble finding material for his research – all he needed was a microscope and a whisky, because springtails are best contemplated with a glass of this noble spirit in hand. So when Mrs Tamura went to Warsaw one autumn to improve her knowledge of the Polish language, Professor Tamura decided to accompany her to study the springtails of the Polish capital. They lived in Powiśle, in an old block at 8 Orłowicza Street, in a flat on the sixth floor. This was a very good choice, because right next to the block is a small park, and in it a round hillock, completely flat on top, with a concrete path running around it. Some think that there was once an amphitheatre here, others that it was a huge gas tank, but now it’s a wild area with maples and acacias, never cultivated, overgrown with nettles and clover, where only cats and dogs roam – and of course, this is paradise for springtails.

That autumn, with the sun shining through the red and gold leaves of the maple and acacia trees, it was a really beautiful spot. Professor Tamura strolled around with genuine pleasure, paying no heed to the nettles that sometimes stung his legs. The soil samples he collected were swarming with springtails and he could observe them all day under the microscope, and then discuss them with Polish springtail researchers. No wonder, then, that he took a shine to Warsaw; he even liked his new flat, although it was nothing like his Japanese home. He had only one traditional Japanese item in the flat – a real samurai sword that had once belonged to his great-grandfather.

One day, a strange and terrible thing happened. Professor Tamura brought a bit of soil with dried leaves home from his afternoon walk and, as usual, settled down to work after dinner. Much to his surprise, there wasn’t a single springtail in the new sample! At first, the professor thought that his microscope had broken, but no, the microscope was working fine. There were no creatures at all in this little bit of soil – no ants or worms; the soil was as dead as if it had come from the Moon. Professor Tamura was very worried and, despite the late hour and the protests of Mrs Tamura, he ran out of the flat and took the lift to the ground floor.

In the light of the streetlamps he saw a tall, dark figure striding along the concrete path surrounding the hillock. It was a huge man in a black coat and hat, holding a large, elongated can. As the professor approached the man, he heard a soft hissing sound.

“Who are you? What are you doing?” asked the professor.

“I’m an inventor and I’m testing my latest invention,” said the man proudly, pressing the trigger on the container. “This spray will kill all insects, mosquitoes, flies, ticks, ants…”

“All of them?” asked the professor.

“Anything shorter than two centimetres,” said the man. “And it won’t harm larger animals at all. Nor people. And it’s extremely, exceptionally efficient. I can do it for the whole planet.”

“What are you talking about? What about springtails? They’re not even insects!”

“Aha, I’ve heard of them. The springtail is some sort of relict. But they’re so small that they’ll be killed too,” said the man.

“But springtails have lived here for four hundred million years! And now they’ll be wiped out? That’s impossible!” cried Professor Tamura.

“Four hundred million years? Isn’t that long enough?” The man laughed and started to walk away, taking huge strides and no longer paying attention to the short old man, who ran after him, panting in exasperation.

The man in the hat climbed some steps into a car park, went down a ramp onto the street and turned right, walked quickly along the side of a brand new, elegant tenement building, then turned right again, into an arcade blockaded by a barrier, and then some glass doors opened in front of him and a fat doorman in a white shirt and tie rose from behind the counter in the entrance hall. Professor Tamura stopped and watched helplessly as the man in the hat headed towards the lift and disappeared behind the shiny doors. He didn’t even try to follow him – the doorman had come to the door and was looking around suspiciously, reaching into his pocket for a phone. Next to the door, on the marble wall, was a sign that read ‘Orłowicz Residence’.

Professor Tamura returned to the courtyard outside his block; it hadn’t even crossed his mind that Mrs Tamura might be worried about him. His heart ached and he couldn’t breathe. He walked to the flat-topped, round hillock where the springtails had been living peacefully, and waded through the nettles until he was standing in the centre. A perfectly round moon shone through the delicate acacia leaves. On all sides, in an incomprehensible configuration, stood tall houses and cuboidal concrete blocks, like megalithic structures around a secret circle.

“I’ll save you! I’ll save you or I’ll die!” shouted Professor Tamura in Japanese.

He went home, where Mrs Tamura was waiting for him with tea, and he told her everything. He took down his great-grandfather’s samurai sword from the wall. Mrs Tamura wiped it down with a cloth, then put on her jacket and shoes and picked up her handbag.

“I’m coming with you. An old Japanese woman won’t arouse suspicion. Let me go first,” she said.

They walked to Orłowicz Residence and waited outside. After a few minutes, a taxi pulled up and a young woman got out. When the door of the residence opened, the old Japanese woman in an outmoded jacket with a black, shiny handbag entered right behind the young woman. The doorman in the white shirt looked at her with indifference, but a few seconds later he stood up, alarmed at the sight of Professor Tamura, who had dashed in behind his wife, holding the large samurai sword in both hands. The doorman reached for the holster on his belt and suddenly froze in fear.

“Where does the inventor in the black hat live?” asked Mrs Tamura.

“On the fifth floor, in the far corner. He has a red door,” said the doorman. He was trembling. He leant against the counter, then crouched down so he was out of sight.

The woman who had entered in front of the Tamuras didn’t notice a thing; she got into the lift and the doors closed.

“We’ll go on foot,” said Mrs Tamura and they started up the stairs. “Slowly. Don’t forget about your heart,” she added.

On the fifth floor, gasping for breath, they rang the bell outside a door padded in red leather. The inventor opened the door, still wearing his black hat, but now sporting a white lab coat in place of his overcoat. He tried to say something, but his voice got stuck in his throat. He gazed at the spot above Professor Tamura’s head as if in a trance. He was holding a spray can.

“Give me that, please,” said Mrs Tamura, opening her black handbag. The inventor handed her the spray and Mrs Tamura carefully put it in her bag.

“Do you have any more of this poison?” asked Mrs Tamura.

“No, no, no!” cried the inventor.

“Are you going to do anything like this again?”

“No!”

“And what are you going to do?”

The inventor turned pale and began to pull on his left earlobe like a sleeping child.

“I don’t know. I just don’t know… I know! I’ll become a chef. A very good chef.” It was clear that he wasn’t lying, that from then on he would try his utmost to be the best chef in the world.

“Okay. Goodbye. Maybe we’ll meet again someday,” said Mrs Tamura.

“Goodbye,” said the inventor, and he closed the door.

This time, the Tamuras took the lift. Professor Tamura looked in the mirror and saw two huge, three-metre high springtails standing behind him like personal bodyguards, bent over to fit in the lift. They stared into the mirror with a multitude of motionless eyes that expressed nothing. No wonder they aroused such fear. They were ghastly. But Professor Tamura looked at them in fascination, trying to remember as many details as possible. He knew he would never have this opportunity again.

“Did you know they were coming with us?” he asked his wife.

“Of course. You know I have eyes in the back of my head. It’s a good job they’re here. Nobody would be scared of you!”

“But I have a samurai sword!” said Professor Tamura.

“That sword of yours is a laughing stock!” said Mrs Tamura, who was collecting Polish sayings. “It hasn’t been sharpened in a hundred years!”

They went out into the street and the springtails went with them. The creatures followed them for a bit until they reached the park, and then they activated those famous spring mechanisms under their tails and jumped, as springtails do, higher than the trees and higher than the houses. And they were gone.

Translated from the Polish by Kate Webster