Saturday, 1st June 1967

2.30pm

“When did this happen?” the policeman asked.

“Come on, how would I know?” the warehouse worker responded, shrugging his shoulders.

“It’d be better if you knew, Wargula,” the shift supervisor Niedzielak barked back. “If you start pulling any tricks, the officer here will lock you up in jail, just like that.”

“Me? What for? It didn’t happen on my shift! Everything was still there on my shift yesterday, and it’s gone today. And I’m supposed to be locked up for that? Ask Gwizdała.”

“Who’s Gwizdała?” the policeman asked with interest. He was plainclothes, yet he was, for all intents and purposes, a real policeman. This was because Sergeant Teofil Olkiewicz happened to be working on a very important case at the H. Cegielski Metal Industry Complex in Poznań (which, until fairly recently, had been called the Joseph Stalin Metal Works). And because the case was important, his supervisors came to the conclusion that Olkiewicz, who was assigned to it, should be dressed to mix in with the crowd. His commander, Lieutenant Wróbel, who did not think very highly of him, explained the gist of the assignment to him, short and sweet:

“You, Olkiewicz, look like a total bonehead and on top of that, you wouldn’t know your own arse from your elbow, so you’re perfect for the job. You’ll blend in with the crows, wander around, talk with people and, of course, you won’t get anything done, but society will know that we are on guard and securing the front line.”

There was an issue though with the blending-in part, because Sergeant Olkiewicz was wearing a white shirt and blue tie with white polka dots, a grey jacket and grey nylon hat. He also took a light coat just in case, which he draped over his shoulder. So actually, he looked more like an American tourist who came to the Poznań International Fair, and not a labourer from the Ceglorz (as the Cegielski factory was nicknamed). So it was no surprise that as soon as he walked into the warehouse, the news that they had sent an undercover agent to sniff around immediately spread among the employees. But even if they had not recognized him, undercover agent Sergeant Olkiewicz knew life all too well and was aware of the fact that nothing would come of ferreting about the factory, because nobody would tell him anything anyway. After all, what should people say about the fact that tools were disappearing? That’s how things go with tools, they disappear; especially since you can’t get anything in the shops, yet you have to make do somehow, and everybody needs a hammer or screwdriver for small repairs at home.

“Well, if the officer here would sit all day on a stool and watch out for these crooks, nothing would be disappearing,” warehouse worker Warguła stated, as he was picking his nose.

“What kind of crazy idea is that?” the supervisor exclaimed, his gaze beaming on Warguła. “You think that the Citizen’s Militia has nothing else to do but hang around the factory doing your job?”

“We’ve got a fireman stationed at the factory who keeps an eye on things all day, so why couldn’t a copper…” the warehouse worker did not give in.

“Keep that up and you’ll be the one ending up behind bars for that, uhm, what was it again…” – Olkiewicz glanced helplessly at Niedzielak, who had been telling him only minutes ago what the commotion was all about, but the officer had forgotten – “…bore machine!”

“An electric drill with changeable bits manufactured in Poland by the Celmar factory,” the supervisor corrected him, using the tone of voice of an expert who had to deal with the technically illiterate.

“Yeah exactly. Electric drill. I understand that small whatnots like a hammer or screwdriver could disappear, but a bore machine? I’m already thinking that it’s a high-profile case we’ve got here and somebody’s going to be doing time for it. And what does a machine like that look like, by the way?”

Olkiewicz had never seen an electric drill. Anyways, it wasn’t just him, because it had only been a few years that equipment like that was being produced in Poland, and, of course, produced exclusively for the needs of large factories.

“It’s a technical marvel, officer,” the supervisor eagerly explained, his eyes sparkling with enthusiasm. “Warguła, go ahead and show it to the sergeant!”

Warguła turned around and disappeared between the rows of shelves on which tools were arranged according to diagrams and guidelines prepared by health and safety specialists, meaning that nobody knew where anything was. But the warehouse worker knew perfectly well where the drills were, because, at least so far, there were only three such devices in his department, or actually, currently two, because one of the drills had disappeared into thin air yesterday.

Olkiewicz and Niedzielak only managed to take a few puffs on their Sport cigarettes when he came back. He placed the valuable device on the counter; it looked a little like a cross between a gun and a Panzerfaust.

“See, what’d I tell you?” the supervisor exclaimed as he tenderly stroked the silver body of the drill like an infatuated lover.

“Looks nice,” Sergeant Olkiewicz agreed, yet he preferred to keep a safe distance from the equipment. He had felt great respect for electricity ever since the time last year when he had decided to repair the table lamp at home; as a result he blew out all the fuses in the building, and the electric shock made his hair stand on end. And that’s the reason for which, in his opinion, an unsightly bald spot started to appear on his forehead. So he had no reason to like electricity.

“Looks are one thing, but wait till you see it work! Mr Warguła, why don’t you fetch us a wood block, we’ll drill some holes in it. You’ll see how it drills holes, officer. All you need to do is hold it from the top. It may look kind of small and it’s made in Poland, but it works like the best Soviet stuff. The only problem are the bits, they keep on breaking; I mean they’re made from poor-quality steel, but we’ve got some in stock, so we can drill all we want, as long as the bastards don’t steal it. Don’t you think, Mr Warguła?”

2.40pm

“You can go to hell with this piece of junk,” muttered Antoni Walczak, owner of a private carpentry shop, as he dismissively eyed the shining silver body of the device.

“What do you mean junk, mister?” said Czechu Mrugała, an assembler working at Ceglorz, visibly offended. “This is a state-of-the-art product of American technical know-how. Not even one Soviet screw inside, not even a single spring from a WWII tank. It’s all American and assembled in the People’s Republic of Poland.”

“And that’s exactly where the issue is, Mr Mrugała. If it were assembled in America, that would be a different story,” Walczak replied, as he scratched his bald head. He would tell everybody the story of how he became bald from all the problems he had with the tax office, which would question his accounts each and every month. But if you wanted to be a relic of the long gone capitalist system and run your own carpentry business in a country run by the worker-peasant establishment, well, you had to keep in mind that said establishment will not turn a blind eye to any shenanigans of the private sector. “Only that if it’s assembled here, you know that half of the parts got lost during assembly, and the other half was stolen.”

“Well sir, if it were as you say, this here bore machine running on electricity would not be on the table in your workshop. But it’s there, sitting there and shining in the sun. And if we could plug it in somewhere, we could drill something here right away to demonstrate.”

Though the one thing Czechu was most afraid of was that the potential buyer would want to turn on the equipment; he had never used an electric drill in his life. In his department, he worked with a hammer and a monkey wrench, and had nothing to do with complicated technical equipment at all. The only thing he did was insert screws into big ship engine bodies, hit them with the hammer so they would go in easier, and once he caught the thread, he would tighten the screws with the wrench. He never needed a drill for anything. Until today. Once he got enough sleep after his night shift, he went up to the factory fence as usual, to a place he knew well to check what his cousin, who worked the morning shift, had been able to swipe. The pickings were usually simple things, like hammers, screwdrivers, tape measures or spirit levels, or anything the enterprising cousin could get his hands on and Czechu could easily sell at the flea market at Rynek Łazarski. The cousin would throw the nicked items over the fence, and the family trade specialist would collect them there. Thanks to the enterprising initiative, both cousins were able to make an additional month’s worth of wages each. While for the thief, the deal was done once the goods went over the fence, things would just get started for the seller. He had to take the spoils, transport them to the flea market, and quickly sell them to one of the traders, for much less than actual selling price, naturally. But there was no other way. Everybody had to get their share.

When today around noon, Czechu discovered in the bushes something that resembled a machine gun with a drill bit, he figured he’d have problems with the contraption. Because who would buy something they didn’t know how to use? So he had to look for a specialist, not a regular trader. That’s why he showed up at Antoni Walczak’s workshop, located in the Dębiec district of Poznań. Yet Walczak himself wasn’t too enthusiastic about the merchandise on offer. How could he have been, when he’d never seen anything like it in his life. Granted, he had read about such a gadget in “Przekrój”. The author of the article even claimed that soon everybody would have an electric drill like that at home, just like everybody has an electric vacuum cleaner. But, as a man who knew something about life, he was quite aware that it was only wishful thinking; for the time being, many people didn’t even have electricity in their homes, not to mention vacuum cleaners.

“No way, Czechu, get this piece of junk out of here and sell it somewhere else. I do just fine with a regular drill; you can take that thing and drill your teeth with it for all I care.”

“Suit yourself,” said Mrugała, and slowly put the drill back into his bag. “We’ll never build socialism with people like you. We’ve got sputniks flying up in the air, and you’re afraid of electricity.”

“It’s not electricity I’m afraid of, but the police,” the privateer muttered and showed the seller the door.

The thief shrugged his shoulders. He didn’t sell the drill, but at least he didn’t have to turn it on and demonstrate how it worked; he’d surely have had a problem with that. That way, the issue solved itself. Fortunately, he knew one guy, a certain Eustachy Gorczyca, who did business at the famous Metalowiec restaurant. Granted, the guy didn’t know anything about technology, but he would buy anything you offered him, though at a lower price.

3.50pm

The queue stretched out maybe about a hundred metres. Yet the people standing in it didn’t have fierce expressions on their faces, typical for queuers waiting at the meat shop. They were quite content, and what was interesting, most of them were smiling. They were talking with each other, joking, and once in a while somebody would burst in laughter. All of them were wearing drill work clothes, the men had black berets, while the women had grey kerchiefs. Only the young ones exposed their bare heads, adorned with trendy if not overly long hairdos, to the warm summer breeze.

The head of the queue crawled up a small set of steps to a door leading to a two-story red brick building. Hanging overhead was an oblong board with a slogan carrying an exceptionally important message:

People of good hard work go straight home on reckoning-day.

Teofil Olkiewicz stopped and lit up a cigarette not far from the door, where the line of waiting people clustered into a tight group that promptly blocked the entry. Once in a while though, somebody would manage to squeeze through the throng and make it outside. Such an individual would stop a few metres from the door, and, visibly happy, peek into a grey envelope. You had to count your pay to see how much they withheld this time round for various workers’ funds and loans to support oppressed third-world nations in the fight for world peace.

“Ah! To hell with them all!” a freckled redhead muttered to himself, as he counted his money.

“How much did they do you in for, Zdzichu?” a young man asked, who like Zdzichu was probably no more than 20 years old.

“They cut off a hundred, the bastards,” Zdzichu Popielak snapped.

“You should be happy. For your hundred, the People’s Army of Vietnam will have a bowl of rice every day for a month.”

“I hope the rice rips their asses apart,” the redhead quipped, and put the envelope in his pocket. “So Marian, I’m going to change and we’ll head out to Metalowiec?” he asked, and his friend smiled, showing two rows of crooked teeth.

Olkiewicz smiled as well. Young labourers were always full of energy and good will. Because who wouldn’t want to enjoy a beer on this warm day? Especially since Metalowiec wasn’t far away. So maybe, instead of just catching the tram and going home, he’d stop by for just a small beer; the more so that there should be a fresh batch coming from the brewery right about now. Teofil also had an envelope with his pay in the pocket of his jacket. And he also had a sum withheld to contribute to the fight of the Vietnamese nation with the American invader, but only five złoty rather than one hundred. Yet losing the fiver was still regrettable, because that was a glass of beer at Metalowiec.

He dropped his cigarette butt and stepped on it with the tip of his shoe. He basically had nothing more to do today. He had written down everything he needed to in his police notebook, tomorrow morning he’d prepare a report based on his conversations today with the shift supervisor and the warehouse worker, and place it in a file specially created for the theft at Ceglorz – he’d pretty much be able to close the case. Because we all know that the hammers and other whatnots will never be found. That bore machine is a different matter though. It will probably show up sooner or later, because some concerned citizen will report that, for example, mister such and such in some privateer workshop is drilling holes using a state-of-the-art machine. And then such a perpetrator will be caught, the equipment will return to its owner, and the Citizen’s Militia will note yet another success in the fight against thievery in the workplace.

He looked again at the slogan hanging over the door where the throng of people huddled together. People of good hard work go straight home on reckoning-day – he read it again and smiled. Indeed, he too would go straight home on reckoning-day. Only that along the way, he’d stop by for a beer, OK maybe two at the most.

Interesting, Teofil thought, that there are even songs about reckoning-day – the day when you get your pay. There’s one song they always sing at all these celebrations and ‘in-honour-of’ ceremonies about the nations of the Earth that are to rise to power. ‘Our day of reckoning won’t stay’, Teofil recalled, but why ‘the people will be judge and jury’? Teofil didn’t know what kind of judge the people would be, but he really didn’t care. After all, the most important thing was that the message conveyed in the song came true on the first of each month; reckoning-day never stayed for long, but it always came.

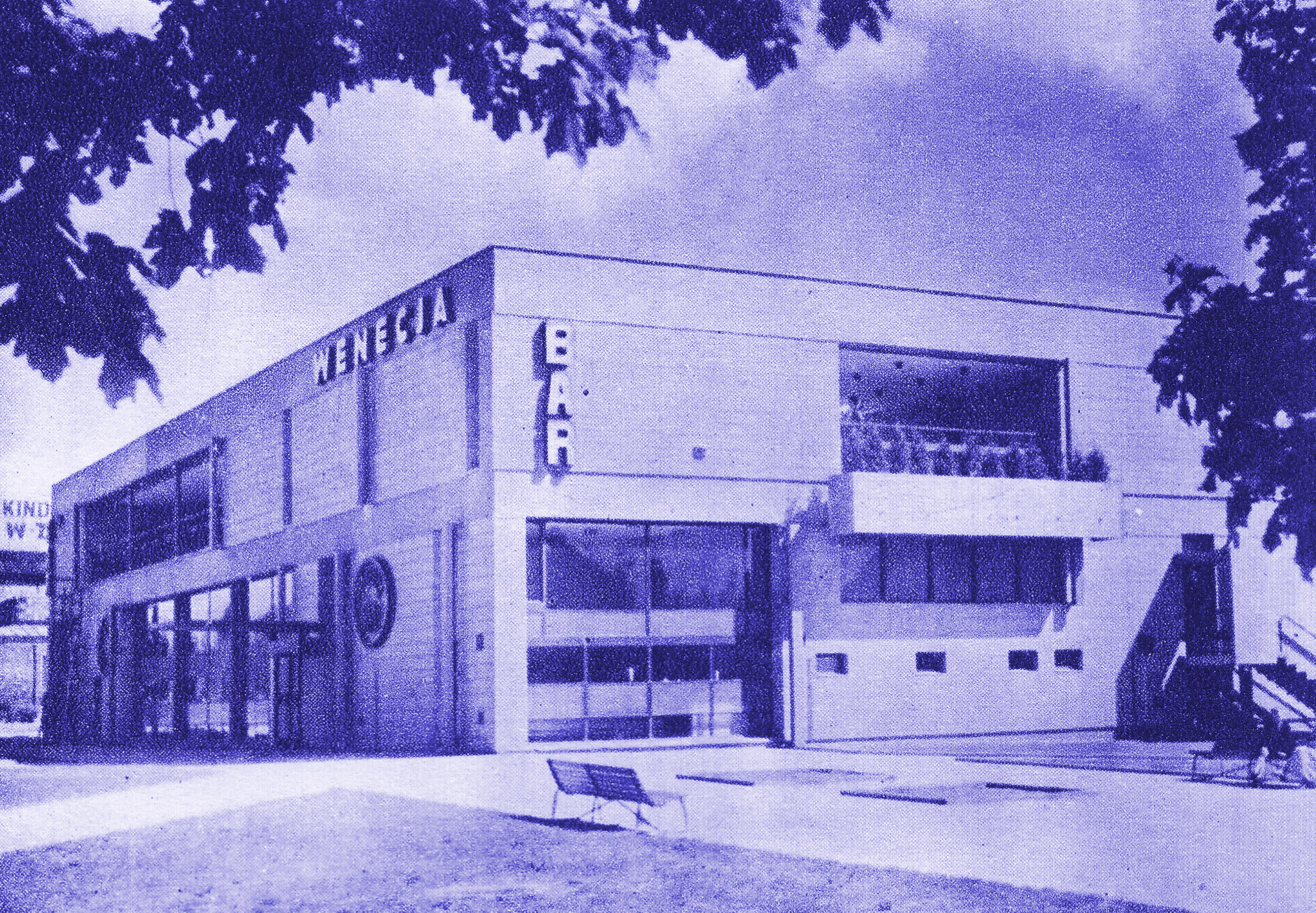

3.10pm

The Metalowiec restaurant on Dzierżynskiego Street was not the fanciest of places. As was usually the case with such establishments, it was decorated in a style that only people with a vivid imagination could consider to be modernist. As a supposed expression of this modern extravagance, one of the walls of the dining hall was covered in various painted patterns that you could not interpret in any meaningful way, even if you had consumed serious doses of vodka. The hall featured a dozen or so square tables standing on metal legs, and each had a small porcelain vase with no flowers, a porcelain napkin-holder with no napkins, and pepper and salt shakers, of which the first was usually empty. The waiters knew very well that no matter how much pepper you put in them, it would be instantly stolen by the guests, so they would add it rarely and a little at a time. And to make life more difficult for the thieves, they also did not provide paper napkins, as the pepper could easily be poured onto the napkin and then carried out in somebody’s pocket. There were no flowers either, because the plastic ones that had been there once were stolen by guests two years ago.

The white tablecloths used were also meant to testify to the unrefined elegance of the place. The only issue was that they were white only at the beginning of the week. Towards the end of the week, they had already become grey and red in certain spots from the borscht, or brown from the sauce, depending on what the kitchen happened to serve. And for the most part, it wasn’t worth changing them; why bother, if people would get the tablecloths dirty anyway, all the more so since they had to wipe their greasy hands on something if there were no napkins at the tables.

As a cultured and savvy man, Sergeant Olkiewicz did not frequent just any old beer hall. After all, those were filled with pathological lowlifes, while he belonged to a social class higher than that of common boozers. He would only drink vodka and chase it with beer, rather than orangeade like the regular slobs; when he drank his shot, he would grab the glass with two fingers and elegantly extend his little finger, totally unneeded at the time. Those who were seated at the table with him recognized straight away that they were dealing with an important person. Because Olkiewicz was not sitting alone. That was simply impossible at this time of day. The place was as busy as a beehive, as it was always on the first of the month; in addition to the senior employees from Cegielski, clerks from the offices and agencies nearby would also come by for a drink. This is because Metalowiec wasn’t some second-class workers’ hangout, but rather a restaurant for people with class and higher aspirations. The labourer crowd drank at ordinary beer halls and beer stalls, while those who had warm and cosy office jobs could indulge in a higher level of state-run gastronomy culture. Because here at Metalowiec, not only were drinks served, but food as well. If you wanted to order vodka, you had to order a starter to go with it. Therefore, dominating the tables were plates of herring à la japonais, vegetable salad, and pettitoes in aspic. However, not many people would try these delicacies, because you never knew what they really contained. On the other hand, vodka and other beverages provided an assurance and guarantee of quality.

“Bring me two more double shots,” Olkiewicz called out to the rather stout waitress with a beehive hairdo, who was squeezing her way through.

“Just a minute, what’s the rush!” she snapped, and went over to a table where a guy in a burgundy jacket had been waving to her for the past 15 minutes; you could see he was beginning to lose his nerve.

Teofil glanced at his empty shot glass and grabbed his beer. He drank just a little to distribute the drinking pleasure over a longer time, because he had no idea when the old bag would come back.

“It’s always the same with these waitresses,” stated a thin clerk in horn-rimmed glasses, who was sitting across from Olkiewicz. “They’re quick to serve those who leave them the change. If you want to get your change to the last złoty, you have to wait.”

“I’ll show her change, just you wait. This isn’t capitalist Paris; it’s a restaurant for the labouring masses of our cities and villages,” stated a guy to the right, dressed in a grey jacket and a fashionable knitted tie. He had long hair, so he was probably an artist working a full-time job. “We should demand the complaint book and write this up.”

“But perhaps dear gentlemen, we should share an entire bottle, rather than wait until the woman brings us individual glasses? She’ll bring us the flask and we pour it ourselves,” the fourth table companion suggested, who did not fit in with the rest in terms of his appearance; he was wearing an ordinary labourer’s jacket and a black beret. Looks like he wanted to rub shoulders with the intelligentsia if he wasn’t drinking beer at a bar, but vodka at a restaurant.

“Not a bad idea,” Teofil agreed; he was actually on his way out having finished his beer, but since such a proposal was put forth, it would be ill-mannered of him to simply leave without having reacted to it. The two other men agreed to such an arrangement, and the labourer got up from the table, walked up to the waitress, and having slipped her the money collected from his companions, he pointed to their table. She nodded her head and after a while, a bottle of vodka appeared, which the worker promptly poured into shot glasses.

Not even five minutes went by and Teofil, armed with the next collected sum, approached the waitress to arrange yet another bottle. As he was squeezing through back to the table, he noticed that the young redhead from the Ceglorz, the one who had been complaining about his pay, was sitting at the window. Seated next to him, sipping a beer, was a slightly older guy who looked a lot like the redhead. “Brothers or cousins,” he thought. Sitting across from them was a sombre thin fellow whose appearance brought to mind a worried pelican. The older cousin was showing him the contents of his enormous bag. “Probably selling some meat he brought from the countryside,” Teofil figured, without any special interest.

“First-class merchandise,” said the older one, while the younger redhead nodded his head to confirm the statement.

As Teofil was passing their table, the thin guy suddenly got up and pushed Teofil so hard that he staggered and would have fallen if it weren’t for some guy who caught him at the last minute.

“Watch what you’re doing, you damn small-town yokel!” Olkiewicz roared and, having brushed off the invisible dust from his jacket collar, he returned to his table.

“You watch it, you lousy scamp!” the thin guy barked back and sat back at his table, as if he had suddenly forgotten that he had been going somewhere.

Having broken through the crowd of drunk white collars, he made it back to his table just as his new friends were pouring the vodka.

“With all the boorish types you get around here, you’re just in no mood to drink,” he murmured as he took his seat. He grabbed the glass and drank it in one throw. He had to hurry, because his ever more enthused table companions were pitching money for a third round.

4.30pm

When he entered the hallway, he immediately smelled the aroma of cabbage soup that filled the entire apartment. It wasn’t until then that he realized how very hungry he was. He had only had drinks at Metalowiec and didn’t touch any of the starters that the waitress brought to the table in large amounts. None of his table companions dared touch the pettitoes in aspic, because they looked like they were just about to crawl off the plate on their own.

“I’m home!” he called from the door, as he was taking his shoes off.

“Geez, where’ve you been roaming about? The soup’s been long ready. I’ve been keeping it on the stove for the past two hours so it won’t get cold.”

“That’s how it is in police work; you never know what you’ll be doing when the morning comes. I was at the Ceglorz. They’re looking for a thief stealing pliers.”

“And you want to find him?” the woman asked surprised, as she knew that her husband couldn’t find anything in the house, not to mention a thief in a factory as big as half of Poznań.

“Find him or not, the police have to search,” Teofil stated as he came into the kitchen.

“And do you have your pay?” she foresightedly asked. She preferred to secure the money right away to make sure that none of it went missing.

“You thought I wouldn’t, ha ha!” he replied and satisfied, dug his hand into the inner left pocket of his jacket. Suddenly, he grimaced. He started nervously looking through his pocket, but didn’t find anything. He thought he might have automatically put it in the right-hand pocket. But it too was empty. He quickly took the jacket off and started to search every nook and cranny. But that didn’t help. He didn’t find any money in his trouser pockets either. All he dug out from there was some loose change.

The last chance was his nylon coat, which he had been carrying about draped over his hand to look elegant, and not because he really needed it. He was rather sure that he didn’t put the money there, but who knows…

The coat held nothing of the sort.

“And what are we going to do now without your pay?” Jadwiga whined, tears starting to flow down her cheeks.

“Don’t you worry a bit,” he replied with the voice of a determined man. “I’ll come back with the cash or I’ll never come back again.”

“Good Lord, what have I done to deserve an old cop and a drunkard on top of that!”

“You haven’t done anything. I’m the one who needs to go find somebody and do something,” he asserted and banged his fist on the table, sending the dish flying and the cabbage soup spilling all over the vinyl tablecloth. He knew that to save face, he would have to act and be merciless in his actions, just like a real Chekist, like that Pavka Korchagin, the main character in the wonderful Soviet film How the Steel Was Tempered, which he had once watched during a junior officer course in Piła. So he changed into his uniform, adjusted his hat to cover his bald forehead, and right away, felt like an upcoming hero.

“I’ll be back soon, Jadwiga!” he called from the hall and ran down the stairs, slamming the door behind him.

He entered the restaurant, but nearly nobody paid any attention to him. A policeman in uniform was a normal sight here, one experienced basically every day. The table at which he had spent the past couple of hours was nearly empty. Seated there was only the guy in glasses, or rather just his body, because the soul imprisoned behind his closed eyelids must have been somewhere in a different and much more interesting reality. The guy was musically snoring like an electric drill and had a smile on his face. Yet Teofil did not need this man for anything. As an experienced policeman, who had consumed vodka from many a bottle, he knew all there was to know about this situation calling for holy vengeance… Oh wait! Marxist dialectic did not allow him as a policeman to call out to anything holy, so he should call out for vengeance to the ‘highest party and governmental officials’. Such thoughts crossed Sergeant Olkiewicz’s mind as he looked around the restaurant. Seated at the table next to the window, where he had been nearly slammed to the floor, was the human pelican. He walked up closer to the skinny guy, who was stoically regarding the depths of his beer glass. You could notice right away that he had had his share of drink and was done with his work of stealing people’s pay for the day. Right now, he was engaged only in entertainment.

“Czesława dear, please get me one more beer!” he said, waving to the waitress. You could see she was on friendly terms with the pelican, because she sprinted to the bar right away to grant the customer’s wish. Meanwhile, as Olkiewicz eyed the skinny lad with his long hands and thin fingers, he immediately remembered how the guy pushed him. And that was the moment at which his thin fingers had to have slipped into the pocket of the sergeant’s jacket. The thief had been unmistakably identified.

Now that he had realized the entire truth, he squeezed through the thinning crowd of increasingly happier and effusive drunkards who were celebrating payday and their return to the group of wealthy people, if only for one day.

“You, pig face, what’s your name?” Teofil asked in a friendly tone as he sat across from the thief. The guy looked at Olkiewicz, surprised. A furrow cut across his forehead, demonstrating the highest intellectual effort. He knew that policeman from somewhere, but couldn’t remember where.

“Good day to you, officer of the people’s government. I am at your full pre-disposal and even in the capacity, as you wish officer, but I just don’t know what the general deal is, gosh darn it. Hell, I don’t know nothing, just like I explained many times to many officers at many stations.”

“First of all, the deal is that you give me your name,” Olkiewicz explained, to make sure that everything was clear to begin with.

“You mean mine?” said the skinny guy, surprised.

“Could be mine, but if you’re wrong, I’ll shoot you like a dog.” As he said that, Teofil noticeably tapped the holster strapped to the belt on his ample belly. The holster that held no gun, because he didn’t even think of taking it out of the cabinet. Anyway, Teofil wasn’t particularly fond of walking around with a weapon. After all, you never know if the silly gun won’t feel like firing on its own.

“OK, so I think I’ll just give you mine. Eustachy Gorczyca, son of Klemens, born on…”

“Born or not, I don’t really care…”

“So, dear officer, what is it that you really want, because I’m thinking that you’re not intending to have a beer with me, gosh darn it?”

“And why not,” Teofil stated just as the waitress was placing a new glass in front of Eustachy. The policeman pulled it towards him and took a big sip right away to release any doubt as to whom the beer now belonged to.

“So should I bring one more, Eustachy?” asked Czesława the waitress, when she realized that the beer had ended up in the wrong throat.

“Well, what do you think, dear Czesława? You think that I’m not disgusting enough to drink with the people’s officer from the same glass? So I’ll ask really elegant like: please bring me another glass, this lack of drink is putting me to sleep.”

The waitress nodded her head without being excessively subservient, yet in a way that is the custom of employees of the collective catering sector who are convinced of their self-dignity; they do not need to bow down to some ordinary scamp in anticipation of a tip, because they can add whatever they like to the bill on their own. And damned be anybody who so much as tries to do anything about it!

“Now you listen to me, you unkempt slob!” Olkiewicz leaned over the table closer to the skinny Gorczyca. “I don’t want to make a fuss here and throw you into jail, because I’d have to write up a special report; and that would be a waste of my official pen and notebook for a slob like you. So in this here regard, I am putting my messenger bag on the table and going to take a piss; when I come back, the cash should be in the bag.”

“What cash?” the thief pretended to be both astonished and in disbelief, but his wise-ass facial expressions made no impression on the fiercely frowning policeman.

“The money you stole in this restaurant on this very day. So if it all doesn’t add up, I’ll shoot you like the slob you are for trying to run from the people’s authority.”

Teofil placed his messenger bag on the table top, got up and proceeded to squeeze through to the toilet. He was sure that his plan would bring the expected results, because he was allowing the bandit to get out of the predicament while saving face and honour.

When he returned to the table five minutes later, Eustachy Gorczyca was gone and so was his messenger bag. Could it be that his perfect plan to get back the stolen money went to hell? So he decided that in this situation, the only thing left for him to do was go back home, take the gun from the cabinet and find the thief. He simply had to shoot the dirtbag to teach him a lesson.

He was about to leave the joint when he noticed the waitress coming his way. The woman was holding his messenger bag.

“I put it away, officer, I put it away when that Gorczyca character left, to make sure that no stinkpot would steal this lovely bag; it would have been a shame. He ran off, but he paid what was due. But I don’t know what to do with his bag, the one he asked me to keep behind the counter. But if he’s being chased after, I guess the police will take his bag?”

Teofil put his messenger bag over his shoulder and followed the waitress to the counter. He had just remembered that the skinny guy was curiously looking inside a bag that the two guys from Ceglorz who looked alike had given him. Maybe indeed it had some fresh meat from the countryside there, or maybe even some ready-to-eat deli meats. He’d take that home instead of his salary, so maybe he’d gain some credibility in Jadwiga’s eyes.

He collected the package and left the restaurant. At least his messenger bag didn’t go missing, because that would have been a shame. And the bag he had seized was almost new and unused, so he was sure he could sell it for good money to some assembler he knew.

Suddenly he stopped, because he remembered that he had a brand new Zenith pen and a calendar notebook with a grey cover. He decided to immediately check whether those exceptionally valuable objects hadn’t gone missing.

He opened the bag and looked inside. The pen was in its place, new and as of yet unused, because somehow he hadn’t had the time nor opportunity to write anything with it. Same went for the untouched calendar with clean pages – it was there. But that wasn’t all. Placed next to it was an envelope, and then even more envelopes… he stopped counting at the third and ran home as fast as he could. It seems that on that day, not only had he lost his salary; in addition to his own money, he had brought Jadwiga six more envelopes full of money. Looks like our thief Gorczyca made a nice winning today.

Satisfied with himself, Teofil sat at the table and lit up a cigarette. His wife poured him a glass of vodka, and she helped herself to a bit of advocaat liqueur. Teofil grimaced at the sight of that yellow goop; but heck, Jadwiga can have whatever poison she wants. It’s her choice and her liver; he, on the other hand, will enjoy a shot of pure vodka – it works wonders for the stomach.

“And what will we do with all that cash, Teo?” the woman asked, “we should return it shouldn’t we…”

“But who will we return it to if it was all stolen? None of the people who were robbed will report it, because it’s a disgrace to get your wages nicked at a restaurant; and actually, who would get which envelope? They’re not signed, they all look the same, and you don’t how much each had. Nothing else we can do about it, Jadwiga. We’ve got to keep the money in a safe place.”

“Where?”

“A savings account is the safest.”

“You’re absolutely right,” she agreed. “Nobody can steal it from there, and if somebody does show up, we can always give it back.”

He nodded. A reasonable wife like that is a treasure, he happily said to himself, she deserves something nice too for all the stress she’s had with the stolen money. He smiled at her, and pointed with his finger.

“Go look in the hallway, there’s a bag next to the door. Take a look inside and see what I brought you.”

She looked at him, thinking he might be joking, but then she got up and went there. After a moment, she came back with the bag.

“What kind of junk is that? And what do I need it for? You won’t make any use of it either, because you can’t even drive a nail in straight.”

That surprised Teofil, as he was convinced that the bag held some special culinary merchandise. He took it from his wife and peeked inside. He saw two hammers and a few screwdrivers. But there was something else wrapped in a worker’s jacket. He carefully pulled that something out and placed it on the table. As he was unwrapping it, he felt his heart beating heavily.

The last rays of sunshine falling through the window joyfully reflected off the silver body of the drill stolen from the Cegielski factory. Will you look at that, he thought, as he eyed the valuable equipment. Tomorrow, Lieutenant Wróbel will find out for himself how much the policeman’s intuition of a certain Olkiewicz is worth. And at that very moment, the words of that song, the one about reckoning and payment, came to mind. ‘Our day of reckoning won’t stay, the people will be judge and jury.’ He finally understood what the song was all about. The people, or the Citizen’s Militia, meaning him. This meant that the day of reckoning was when he was meant to judge wrong doings and administer socialist justice. And thanks to that, he had seven wage envelopes instead of one, the thief had none, and on top of that the People’s Republic had regained one missing drill.

“I tell you, Jadwiga, the ‘Standard of Revolt’ is a wise song after all,” he stated, as he smiled to his wife. Yet she made the sign of the cross when she heard the heresy, just in case; she knew all too well that wise songs are sung in church, and not at meetings or ceremonies.

A quite satisfied Teofil reached for his glass and emptied it. A toast to the drill.

Translated from the Polish by Mark Ordon