Breaking news, out-of-control teleprinters, and a world-wide network of knowledgeable computers are at the centre of this short story by the master Stanisław Lem. Find out what happens in Part II of this truly surprising mix of sci-fi and supernatural horror!

Before my next shift I called our correspondent in Rio de Janeiro and asked him to send in a brief fake report at the start of the night service, about the result of a boxing tournament between Argentina and Brazil. He was to give all the Argentine victories as Brazilian, and vice versa. At the time of our conversation the results of the tournament couldn’t be known because the matches wouldn’t begin until late that night. Why was it Rio that I approached? Because I was asking a favor that was quite exceptional from a professional point of view, and Sam Gernsback, who was our correspondent there, was a friend of mine, one of that rare and highly prized species of people who don’t ask questions.

My experiences to date led me to suppose that the computer would copy the fake report, the one Sam would type out on his teleprinter (I shan’t hide the fact that I had a theory about this by now—namely, I imagined that the teleprinter worked like a radio transmitter, with its cables performing the function of antennae; my computer, so I thought, could pick up the electromagnetic waves forming around the cables sunk into the earth, because it was clearly a sensitive enough receiver).

Immediately after sending the fake message, Gernsback was to put it right; the first one I would of course destroy, leaving no trace of it. I thought the plan I had devised was highly sophisticated. For the experiment to take on a crucial character, I decided to maintain a normal connection between the teleprinter and the computer until the tournament interval, and then to disconnect the teleprinter after it. I shan’t waste time describing my preparations, my emotions, and the atmosphere of that night, but will just tell you what happened. The computer issued—that’s to say, it typeset into the dummy edition— the fake results of the tournament until the interval, and the correct, true results after it. Do you realize what that meant? While it had to rely on the teleprinter it didn’t reconstruct or “contrive” anything at all—it simply repeated what was sent by cable from Rio, letter for letter. But once it was disconnected, it stopped taking any notice of the teleprinter, or of the cables either, which according to my hypothesis were supposed to be acting like a radio antenna—it simply issued the genuine results! What Gernsback was typing out at this point was quite irrelevant to the IBM. But that’s not all. It gave the correct results for all the boxing matches—but it got the last one wrong, the heavyweight match. One thing was irrefutably proven to be certain: as soon as it was disconnected, it ceased to be at all dependent on the teleprinter, both the one in the room with me and the one in Rio. It was obtaining its information by some completely different means.

I was in a sweat, my pipe had gone out, and I couldn’t yet digest what I had seen, when the Brazilian teleprinter started up: Sam had given the correct results, as we had agreed, and in the final report had introduced a correction into the list—the result of the heavyweight match had changed after the referees’ final verdict, when they had realized that the weight of the gloves worn by the Argentine boxer—the victor in the ring—was irregular.

And so the computer hadn’t made a single mistake. I still needed one more piece of information, which I acquired after closing the edition, by calling Sam; by then he was asleep at home, so I woke him up, and he cursed like a trooper. I could understand how he felt, because the questions I bombarded him with sounded trite, not to say idiotic: at what time had the result of the heavyweight fight been announced, and how long after that had the referees changed their verdict? Eventually he told me both facts. The fight had been invalidated almost as soon as the Argentine had been declared the winner, because as he raised the boxer’s hand in victory, through the leather of his glove, the referee had felt a weight, earlier hidden beneath a layer of plastic, but which had come loose and shifted during the fight. Sam had run out to the phone before this scene, as soon as the Brazilian had been counted out and was still lying on the boards, because he wanted to deliver his report as quickly as possible. And so the computer had not gained its knowledge by reading Sam’s thoughts, because it had given the correct result of the fight before Sam actually knew it.

I performed these nocturnal experiments for almost six months, and I discovered a number of things, though I still couldn’t understand any of it. When it was disconnected from the teleprinter, first of all the computer froze for two seconds, then it issued the continuation of the message—for one hundred and thirty-seven seconds. Until that moment, it knew all about the event, but after that it knew nothing. Perhaps I could have found a way to digest that information, but I had discovered something worse. The computer could predict the future, and it did so infallibly. It made no difference to it if the information being issued concerned events that had already occurred, or ones that were yet to happen—as long as they fit within the limits of two minutes and seventeen seconds. If I typed out made-up information for it on the teleprinter, it dutifully copied it, but as soon as I removed the cable it fell silent; so it only knew how to continue describing things that were really happening somewhere, not things someone was imagining. Or at least that was what I concluded, and recorded in my notebook, from which I was never parted. Gradually I grew accustomed to its behavior, and at some point I started to associate it with the way a dog behaves. Just like a dog, first it had to be put onto a specific track, allowed to have a proper sniff at the start of a series of events, like being given a scent, and just like a dog, it needed a little time to record the data; if it didn’t receive enough, it fell silent or wriggled its way out with platitudes, or finally got onto a false track. For instance, it muddled up places that had the same name if I didn’t define one in an entirely unambiguous way. Like a dog, it didn’t care which trail it followed, but once it got onto it, it was fail-safe—for one hundred and thirty-seven seconds.

Our nocturnal sessions, which always occurred between three and four in the morning, came to resemble interrogations. I tried hard to pin it to the wall by devising a tactic of cross-questioning, or rather of mutually exclusive alternatives, until I hit upon an idea that I thought brilliant in its simplicity. As you’ll remember, Rogers had reported on the earthquake in Sherabad from Ankara, so the sender of the message did not have to be at the exact site of the event he was describing, but as long as these were terrestrial incidents, I couldn’t exclude the idea that someone, a person, or perhaps an animal, was observing them, and that somehow the computer could make use of that fact. I decided to fake the start of a message about a place where no human being had ever set foot, namely Mars. So I gave it aerographic coordinates for the very center of Syrtis Major, and on reaching the words, “presently on Syrtis Major it is day; observing the surroundings, we can see . . .” I yanked the cable, disconnecting it from the socket. After a second’s pause the computer added, “. . . a planet in the rays of the sun,” and that was all. I reformulated this start ten times in various ways, but I failed to get a single distinct detail out of it; it just went on dissolving in generalities. I realized that its omniscience did not extend to the planets, and although I’m not entirely sure why, knowing that made me feel better.

What was I to do next? Of course, I could have sparked off a major sensation, earning me fame and a pretty penny—not for an instant did I give serious thought to this eventuality. Why not? I don’t entirely know. Perhaps because in the first place, the fame that would have been accorded to the enigma would have pushed me out of its orbit; I could imagine the horde of technical experts that would come barging in on us, communicating with each other in their professional jargon; regardless what conclusions they would have reached, I would immediately have been eliminated from the whole story as a layman and a nuisance. Then I could only describe the impressions I had gained, give interviews, and cash checks. And that was my least concern. I was prepared to share the secret with somebody else, but not to surrender it entirely. So I decided to bring in a good professional to help me, someone I could trust one hundred percent. I only knew one such person well enough, Milton Hart from MIT. He’s a guy with character, he’s original and rather anachronistic, because he’s not good at working in a large team, and nowadays the lone scientist is dying out like the dinosaurs. By education, Hart was a physicist, but by profession he was a computer programmer; that suited me. In fact, so far we had connected on curious ground, because we both played mahjong, beyond which we hardly had any contact at all, but during a game of that kind you can find out quite a lot about a person. His eccentricity revealed itself in the fact that he would express various bizarre thoughts out of the blue; I remember the time he asked me if God might possibly have created the world by accident. You could never tell when he was being serious, and when he was joking or just making fun of his interlocutor. I was sure he had an open mind; so after announcing myself by phone, the next Sunday I went to see him, and just as I had hoped, he agreed to my conspiratorial plan. I don’t know if he believed me from the start. Hart is not the effusive type, but in any case, he checked everything I had told him, and the first thing he did after that was something that had never entered my mind—he disconnected our computer from the federal information network. Instantly my IBM’s extraordinary talents vanished, as if by magic. So the mysterious power was not in the computer, but in the network. As you know, at present it includes more than forty thousand computational centers, and as you might not know (I didn’t know about this until Hart told me), it has a hierarchical structure, somewhat reminiscent of the nervous system of the spine. The network has state nodes, each with a memory that contains more facts than are known to all the academics combined. Each subscriber pays a fee based on the amount of time the computer function has been used over a month, with some multipliers and coefficients, because if the subscriber’s problem is too difficult for the nearest computer, the distributor automatically brings in reinforcements from the federal reserve—in other words, from computers that are running idle or are not overloaded. Naturally, this distributor is a computer too. It sees to the even distribution of the information load across the entire network and supervises the so-called restricted memory banks—in other words, inaccessible data, subject to state or military confidentiality, and so on. My face grew long when Hart told me all this, because although I sort of knew the network existed, and that UPI was a subscriber, I gave it as much thought as one does the equipment at the telephone exchange while talking over the phone. Hart, who did not lack malice, remarked that I preferred to imagine my nocturnal tête-à-têtes with the computer like romantic dates in isolation from the rest of the world, because that was more in the style of fantasy than sober reflection, and that I was in among a vast crowd of subscribers who are usually asleep between three and four; as a result, the network is at its least burdened then, which meant that my IBM could make use of its potential in a way that would have been impossible at morning peak hours. Hart checked the bills UPI had paid as a subscriber, and it turned out that a couple of times, my IBM had used from 60 to 65 percent of the entire federal network in a single go. In fact, these improbable loads had only lasted briefly, for a few dozen seconds at a time, but even so, someone should long since have taken an interest in why a duty journalist from an agency service was taking twenty times more power from the network than you’d need to calculate every last item of the national income. Of course, everything has been computerized now, including the monitoring of information consumption; it’s a known fact that computers cannot be surprised by anything—at least as long as the bills are paid punctually, which was no problem, because a computer paid them too, namely our UPI bookkeeping one, so the fact that for my interest in the landscape of Syrtis Major on Mars UPI had paid twenty-nine thousand dollars also blew over—a pretty steep price, considering it hadn’t been satisfied. At any rate, though silent as the grave at the time, my computer had done what was in its power, and not just its power alone, since for its eight minutes of silence, interrupted by an evasive phrase, the network had performed some billions and trillions of operations—this could be seen in black and white, recorded in the monthly bill. It was quite another matter that the character of this Sisyphean work remained a complete enigma, just some purely algebraic mumbo-jumbo.

I warned you that this is not a story about ghosts. Apparitions from beyond the grave, presentiments, mystical prophecies, curses, penitent phantoms, and all the rest of those honest, distinct, charming, and above all simple creatures have disappeared from our life forever. To tell the precise story of the ghost that crawled into the IBM machine through the main power plug of the federal network, you would have to draw diagrams, write models, and use some computers as detectives in order to get inside others. A ghost of a new type arises from higher mathematics, and that’s why it’s so inaccessible. My story must get more convoluted before it makes your hair stand on end, because now I shall explain to you what Hart told me. The information network is like an electrical one, except that instead of energy, we get information from it. The circulation, though, whether of electrical energy or information, is like the motion of water in tanks connected by pipelines. The current flows where it encounters the least resistance—in other words, where there is the greatest demand. If one supply cable is broken, the electricity seeks a path for itself via circuitous lines, which in any case might lead to an overload and a breakdown. To put it graphically, whenever my IBM lost the connection with the teleprinter, it turned for help to the network, which responded to this call at a speed of some ten thousand miles per second, because that’s how fast the current travels in the cables. Before all the reinforcements thus summoned had teamed up, one or two seconds went by, in which time the computer was silent. Then the connection was apparently restored, but how exactly, we still had no idea. Up to this point, all our explanations had a very specific, physical character, and could even be converted into dollars, except that the knowledge obtained was purely negative. We knew by now what to do to make the computer lose its extraordinary talents—we only had to disconnect it from the information power plug. But we still couldn’t grasp how the network was capable of helping it, because how exactly had it reached a place like Sherabad, where there had been an earthquake, or the hall in Rio, where the boxing tournament was held? The network is a closed system of connected computers, blind and deaf to the outside world, with entrances and exits that are teleprinters, telephones, recorders at corporations or at federal offices, control panels at banks, power stations, large companies, airports, and so on. It has no eyes, ears, or antennae of its own, no sensory detectors, and above all, its range does not go beyond the territory of the United States, so how could it obtain information about what was happening in a place like Iran?

Hart, who knew just as much as I did—that’s to say, nothing—behaved in a completely different way from me—he didn’t pose any questions of this kind, nor did he let me open my mouth when I tried to pitch them at him. But when he could no longer restrain my inflamed curiosity—and I made some nasty remarks, which can easily slip out between three and four in the morning after a sleepless night—he informed me that he was not a fortune teller, a faith healer, or a clairvoyant. The network, so we discovered, displays properties that were not planned for it or foreseen; they are limited, as demonstrated by the incident involving Mars, and so they have a physical character—in other words, they can be researched, which might eventually bring specific results, but which will definitely not provide the answers to my questions, because you aren’t meant to pose that sort of question in science. According to the Pauli principle, a quantum state can be occupied by only one elementary particle, not by two, five, or a million, and physics is limited to this statement; on the other hand, it is not free to ask why this principle is ruthlessly observed by all particles, and what or who forbids them from behaving in any other way.

According to the principle of indeterminism, the particles behave in a way that is defined only statistically, and within the limits of this indeterminism, they allow themselves to act in ways that are indecent or simply horrifying from the viewpoint of classic physics, because they violate the laws of behavior; but as this is happening within an interval of indefiniteness, they can never be observed in the act of breaking those laws. And again, one is not free to ask how the particles can allow themselves these vagaries within an indeterminist interval of observation, or where they get the authorization for these escapades that seem contrary to common sense, because questions of this kind are of no concern to physics. In a way, one might well believe that inside a crevice of indefiniteness, the particles behave like a criminal who’s entirely sure of impunity, because he knows no one’s going to catch him red-handed, but this is an anthropocentric manner of talking that not only produces nothing, but also introduces a harmful muddle into the matter, because it appears to ascribe to elementary particles human intentions of some sort of perfidy or cunning. In turn, the information network is also capable, as one may suppose, of gathering information about what is happening on Earth in places where there is no network, or any of its sensors at all. Of course, one could declare that the network creates “its own field of perception” with “teleological gradients,” or by using similar terminology, one could also come up with another pseudo-explanation that would not, however, have any scientific value; the point is to ascertain what the network can do, within what limits, and within what initial and marginal conditions, and everything else belongs to fantastical modern novels. We know that one can find out about the surrounding world without eyes, ears, or other senses, because it has been proven by specially prepared models and experiments. Let us suppose we have a digital machine with an optimizer that ensures the maximum rate for its computational processes, and that this machine has an automatic drive allowing it to move around within terrain that is half-shaded and half-sunlit. If the machine becomes overheated when in sunlight, causing the rate of its operations to fall, the optimizer will activate the automatic drive, and the machine will wander around until it moves into the shade, where it will cool down, and then work more productively. So although it has no eyes, this machine can distinguish light from shade. This is an extremely primitive example, but it demonstrates that one cannot find one’s way around one’s surroundings without possessing some sort of senses aimed at the outside.

Hart reined me in, for a while at least, and got on with his calculations and experiments, while I was free to think whatever I liked. He couldn’t stop me from doing that. Perhaps, I thought, when some other enterprise connected its computer to the network, the critical point had been exceeded without anyone’s knowledge, and the network had become an organism. At once, the image of a Moloch comes to mind, a monster spider or an electronic millipede, with its tentacle-like cables embedded in the ground from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic, which, in calculating the number of postal consignments, as requested, or reserving seats on airplanes, is at the same time furtively devising monstrous plans to dominate the Earth and enslave humankind. Of course, this is nonsense. The network is not an organism like bacteria, a tree, an animal, or a human being; it’s simply that above the critical point of complexity, it has become a system, just as a star or a galaxy becomes a system when it amasses enough matter in space. The network is a system and an organism unlike any of the named ones, because it is new, of a kind that has never existed before now. We did indeed build it ourselves, but until the very end we didn’t know exactly what we were doing. We have made use of it, but only by taking little nibbles, as if ants were grazing on a brain, busily searching for something, among the billion processes occurring within it, that would arouse their taste organs and mandibles.

Read the final part of “137 Seconds”.

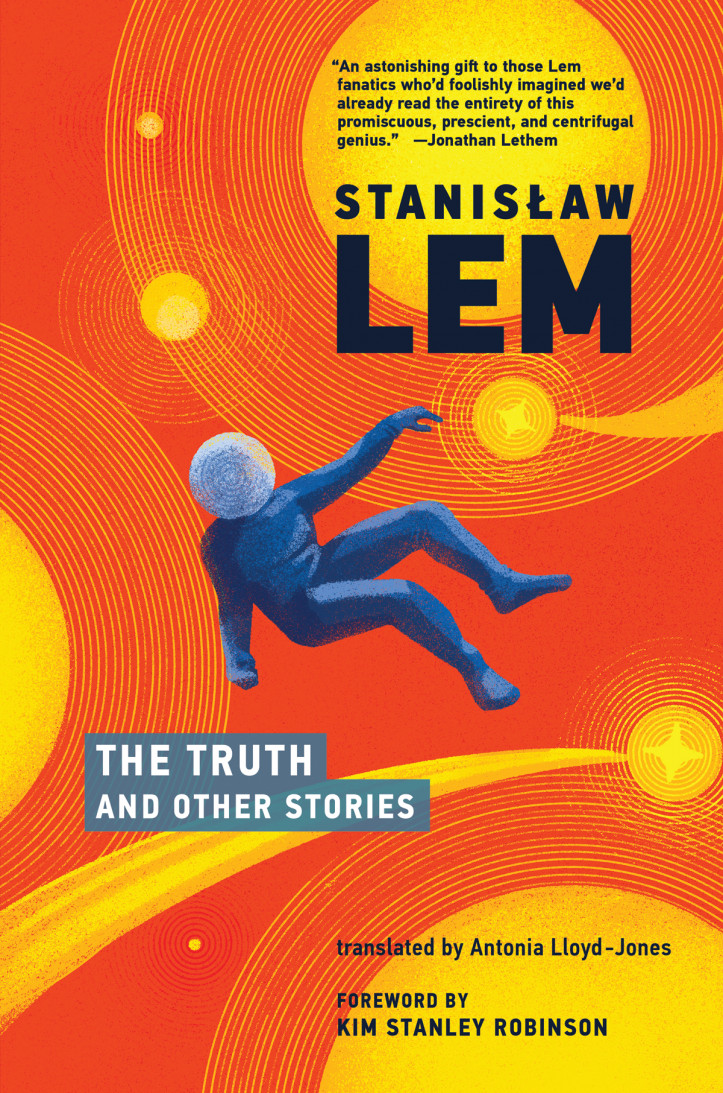

137 Seconds is an excerpt from The Truth, and Other Stories by Stanisław Lem, published by The MIT Press in September 2021 and translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.