When Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism was published in 1909, the Russians welcomed it like an epiphany. However, a mere five years later it had become clear that while the avant-garde movement in the East was hurtling along just as fast as the Italian movement led by the pioneers of modernity, it was headed in a very different direction.

The atmosphere was tense before Marinetti’s first reading in the auditorium of the Kalashnikov Stock Exchange in St. Petersburg. A day earlier, Nikolai Kulbin had gathered an informal welcoming committee of local Futurists at his home. The host – a popularizer and theoretician of new art who was older than the rest of the attendees and held prestigious positions as state councillor and doctor of the General Staff of the Russian Army – tried to coerce everyone into giving the Italian Futurist a friendly welcome. He was afraid of an embarrassing scene, remembering an interview that had appeared in a Moscow newspaper a few days before Marinetti’s arrival in Russia. In the interview, Mikhail Larionov – a co-founder of Rayonism, the second-most radical branch of the Russian avant-garde movement (after Suprematism) – argued that the Italian guest should be greeted with rotten eggs for betraying his previously proclaimed views.

Contrary to expectations, the visitor was greeted by bouquets of flowers on the platform of Moscow’s train station instead of a hail of chicken eggs. However, the flowers were given to him by representatives of the traditional literary establishment. Due to the absence of the leading Russian Futurists – David Burliuk, Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vasily Kamensky – while they were travelling through southern Russia, Marinetti didn’t have an opportunity to meet any of the major figures of the new avant-garde movement in Moscow. For this captain deprived of an army, the Russian press’s raptures over his vivacity and oratorical talent were hardly any consolation. Disappointed by the first leg of his journey to the East, he hurried to St. Petersburg.

Scuffles in the audience

Playing on local patriotism, Nikolai Kulbin urged those who had come to hear Marinetti in St. Petersburg to behave better than their Moscow counterparts and greet the guest like true Europeans. “The only Asiatics were the two of us: Khlebnikov and I,” the poet Benedikt Livshits later recalled in his book The One and a Half-Eyed Archer. The two poets decided to challenge Marinetti, who was visiting Russia in January 1914 like a boss from headquarters visiting a provincial branch. That very night, they composed a proclamation containing the following lines:

Today some natives and the Italian colony by the Neva, for personal reasons, are prostrating themselves at the feet of Marinetti. They are betraying the first advance of Russian art along the path of freedom and honour and are placing the noble neck of Asia under the yoke of Europe.

[…]

People strong of will refuse to get involved. They remember the law of hospitality, but their bow is taut and their brow is angry.

Foreigner, don’t forget where you are!

The lace of servility on the sheep of hospitality.

In the morning, Khlebnikov took the text to a printing house and then, right before Marinetti’s speech began, handed half of the freshly-printed pamphlets to his co-conspirator. When Kulbin noticed this, he ran off the stage and snatched the pamphlets from Livshits, then rushed toward the back rows behind Khlebnikov. A scuffle must have broken out there, because when Kulbin returned to his seat on the stage, he looked, as Livshits put it, like “a man who had just jumped out of a train going at full speed.”

The numerous factions of the Russian avant-garde had to choose between Europe and Asia in their search for a distinct identity. The essence of this discussion reflected broader historical processes that had ravaged modern Russia since at least the reign of Peter I, pushing it one way or the other. The altercation in the auditorium of the St. Petersburg Stock Exchange – in a city that, according to the vision of the tsar who had founded it, was meant to be a window on the West – gained an additional, symbolic dimension. In the second half of the 19th century, the idea of an Asiatic identity was gaining momentum and donning imperial colours. However, these faded in the wake of the defeat suffered by the Russian army in 1905 during the war with Japan. No one was seriously thinking about a Third Rome after that. The manifestos of the Russian Futurists remained in the realm of an artistic utopia, and the declared Asiatic identity was no more than a metaphysical slogan. Italian Futurism, due to its support of the Italo-Turkish War and Italy’s colonial ambitions, was shifting towards an ideology associated with politics, eventually ending up on the side of fascism.

New trends

Hylaea – the most important Futurist group, founded in 1910 – took its name from a text by Herodotus. The historian used the term to describe the steppe on the Dnieper River near the Black Sea inhabited by the Scythians, a people who symbolized the eastern, barbarian threat to the Greek population. The name of the group, which didn’t sound very Futuristic, hinted at its ancient roots and Eurasian distinctiveness.

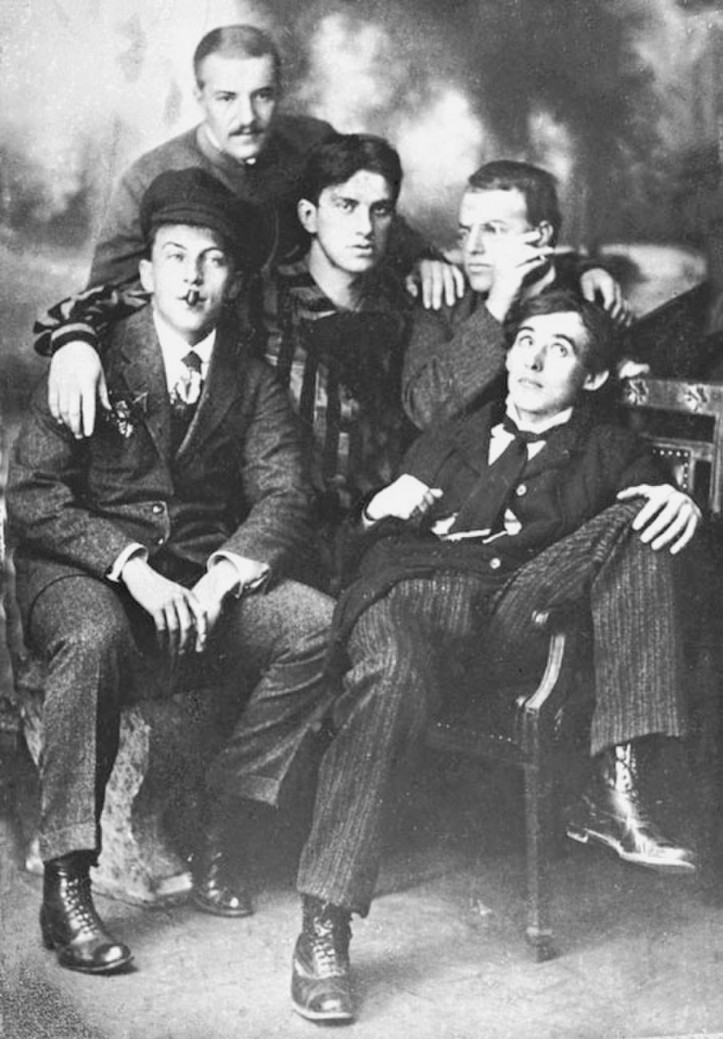

The central figure of the group was David Burliuk, whose family managed a huge estate on the Black Sea steppe. Burliuk – of enormous stature and with an unquenchable passion for life, “a dubious poet, good painter, and brilliant organizer,” with one glass eye, a brightly coloured frock coat, and a horse painted on his cheek – was more suited than anyone else to be a herald of the new art. When he met Mikhail Larionov, the future founder of Russian abstractionism, in Moscow in 1907, they struck up an instant friendship, which turned into an equally intense animosity several years later.

A year later, David, his brother Vladimir and Alexandra Exter organized an exhibition in Kyiv called Zveno (‘The Link’), which was the first exhibition in the Russian Empire to feature paintings by young people who were distancing themselves from formalism. The exhibition featured works not only by the organizers, but also by many other artists including Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova and Aristarkh Lentulov. The latter had previously introduced the Burliuk brothers to Kulbin, the organizer of the first exhibition in St. Petersburg, which had occurred slightly earlier and had featured, in addition to the brothers, the prominent painter and poet Elena Guro and her husband Mikhail Matyushin – a violinist, and later a theorist and publisher of art prints. The paintings by the above-mentioned artists included Post-Impressionist landscapes heralding a turning point: a departure from representative fidelity and a shift in emphasis to the subjectivity of an artist’s experience. Psychological motifs were also explored. Kulbin was particularly interested in dissonances in the psyche and the possibility of reflecting them in art. Despite his considerable contribution to the promotion of new artistic trends, he was still mentally stuck in 19th-century Decadence. At the exhibition, he devoted a great deal of space to academic art. The eclecticism offended the younger members of the group. Eager to become independent, they established the Union of Youth in 1910, through which they organized exhibitions and published their own newsletter.

The young artists often met in a flat owned by Matyushin and Guro. The meetings were attended by Vasily Kamensky, a poet and one of the first Russian aviators (could there be a better profession for a Futurist?). One time, he brought a friend who was a student of mathematics – the shy and absent-minded Viktor (soon Velimir) Khlebnikov. In this way, a group of poets began to form. The first public appearance of the group’s work was in A Trap for Judges, published in 1910. Printed on wallpaper, illustrated with Burliuk’s drawings, and full of bizarre prose and poetry that violated spelling rules, it was meant to be a bomb that would disrupt the literary milieu dominated by the Symbolists. All the writers and artists in the group were certain that the publication was going to cause a literary revolution, and they joked about the reactions they expected from readers. Kamensky recalled, “We understood perfectly well that we were laying the foundations of a ‘new epoch in literature’.” This bomb, however, full of semi-amateurish poetic material (with the exception of three poems by Khlebnikov), turned out to be a misfire, at best. Excerpts were reprinted by the symbolist magazine Apollon – but in its humour section.

David Burliuk’s voracity caused him to spread the ideas of the new art with indefatigable energy, regardless of temporary setbacks, and to recruit new figures to the movement. The most important of these was Vladimir Mayakovsky, whom he met in 1911 at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (from which they were both expelled three years later). When Mayakovsky timidly recited to him two poems by a ‘friend’, David guessed he was the author and perceived a great future poet in him. “[…] Burliuk and Mayakovsky were carrying on a particularly feverish activity in Moscow. They missed no opportunity for self-advertisement and took part in all the debates – either as speakers or as critics. They tried to squeeze into every literary and artistic event in Moscow,” Livshits remarked on the doubled power of the new art’s proponents.

Intuitive games of chance

Had Marinetti visited Russia in that first period when attempts to formulate a new artistic and literary language were still very tentative, he would probably have been lauded as an apostle of the ‘new’. In 1914, however, he failed to inspire enthusiasm. “Marinetti gave me the impression of a very talented man, gifted with the artistry of words. He beautifully imitated the whirr of the propeller, the explosion, the snare drum, demonstrating, as it were, the coming European war. All in all, it seemed like merely a juggling act to me. Not only to me, but to our entire group,” Matyushin recalled. “‘We have come to know a new beauty – the beauty of speed. It is evident in the zoom of an automobile, in the flight of an aeroplane, and we must incarnate it in art! Dynamism is the basic principle of contemporaneity!’ We had heard this a long time ago. It was nothing but a rehash of the manifestos published several years before,” stated a clearly bored Livshits when quoting Marinetti’s speech years later.

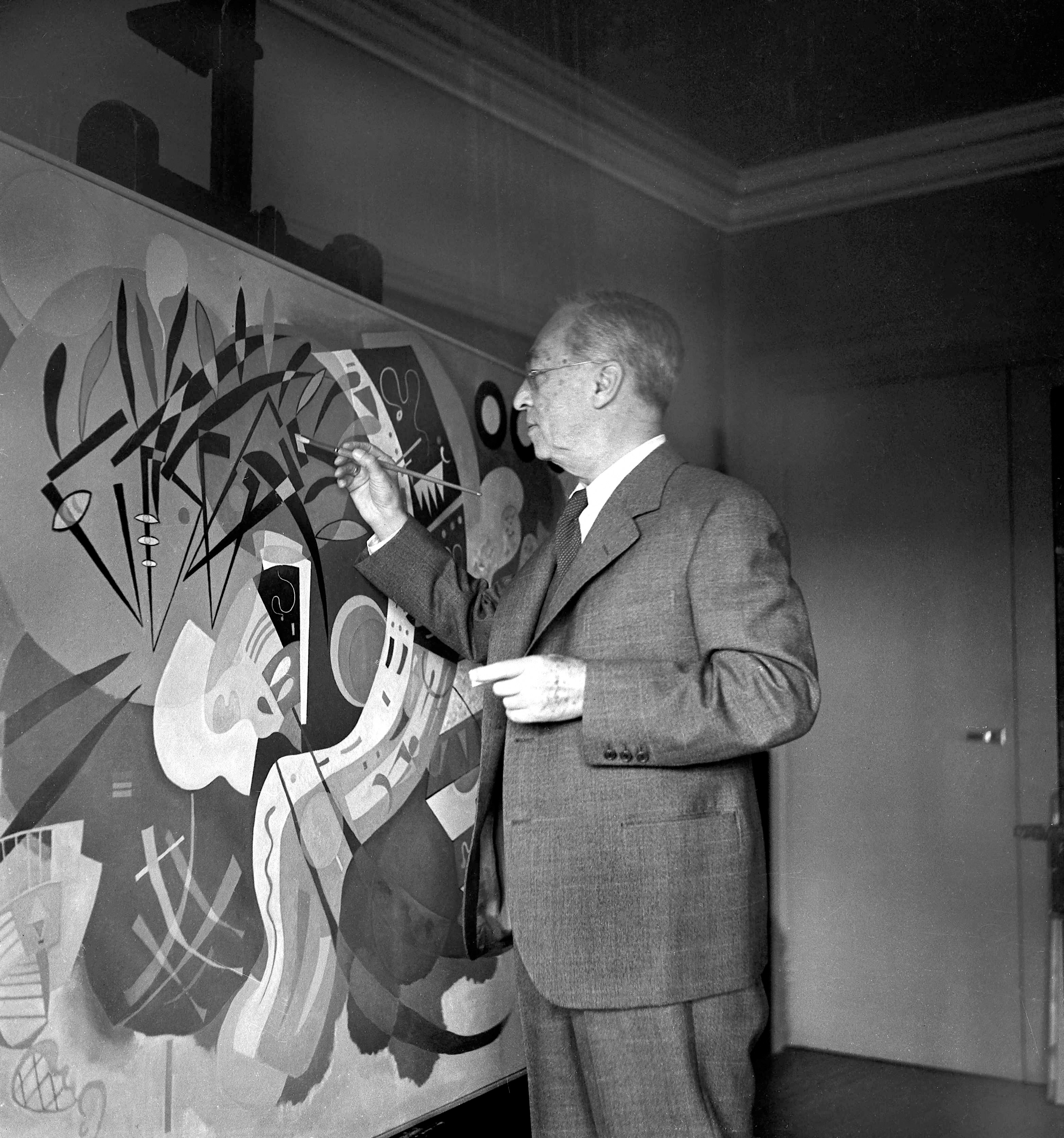

The years 1912–1913 were a period of accelerated growth for the Russian avant-garde. Its representatives drew on Western models, a wealth of talent and individuality; they established new groups, forming alliances with some while clashing with others, and developed their own language. Russian artists maintained close contact with Kandinsky’s German Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, and had the opportunity to admire paintings by the École de Paris hanging in the palaces of Moscow’s world-class art collectors, Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. And finally, they were able to view new works in photographs: Livshits recalled a photo of a Picasso painting shown to them by Alexandra Exter (one of the most ‘Western’ artists of the group), over which Burliuk and his wife huddled like conspirators over a map of an enemy’s secret fortress. Immediately after digesting the work, they churned out paintings of their own, thus incurring a debt to the brilliant Spaniard.

They read Henri Bergson. His works emphasizing the role of intuition found fertile soil in Russia. This approach was particularly important for Russian avant-garde artists. In an article published in the Union of Youth’s almanac, Vladimir Markov differentiated between the constructive, ratio-based approach to art that originated in ancient Greece and the alogical, non-constructive approach based on intuition and ‘feeling’, associated with the East. Irregularity and non-rationality as an artistic technique became the hallmark of the first wave of the Russian avant-garde. The Neo-Primitivists were interested in anti-aesthetic folk art, and the poetic space was filled by the transrational poems of Khlebnikov and Kruchyonykh. The role of chance, games, and loosening of rules in the creative act was meant to result in the expression of an inner, unmediated truth. Thus, it was flawed art, not academic art, that gained prominence – by reaching the essence of the creator, and thus also the essence of the object being represented. This brought the Russian ‘leftist’ artists closer to the pre-Dadaist pastime of playing with absurdity, and further from the severe character of Italian Futurism. In this conglomerate of inspirations there was no shortage of manifestos of Italian Futurism, whose main popularizers were the Moscow-based writers Ilya Zdanevich and Vadim Shershenevich. Interest in the ‘city’, which is evident in Mayakovsky’s early work, is a clear Italian influence. Urban themes, however, were pushed into the background when the great ‘I’ of the brilliant artist entered the stage.

The past is constricted

The canvases on which Larionov presented waves of light refracting on objects drew directly from the aesthetics of Umberto Boccioni’s works. Rayonism, however, was developed by the founder of this movement into something more than just a style of art. It became a philosophical tool that could be used to analyse reality. The main element that united the two groups was a disparaging attitude towards the past.

This was intuitively sensed by David Burliuk when observing art viewers and critics – for whom the disputes between the two groups of Russian Futurists, Jack of Diamonds and Donkey’s Tail, concerning the innovations of Cubism were very hermetic. However, for havoc to break out during lectures it was enough to attack not even Michelangelo or Titian – who, according to Livshits, were no longer sacred – but Russian proponents of academic art, such as Nikolai Bodarevsky and Ilya Repin. Manifestos became a useful tool in the fight against the literary establishment. In a manifesto titled A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, published in late 1912, the authors proclaimed: “Only we are the face of our time; in the literary art we are sounding the horn of time. The past is constricted. The Academy and Pushkin are less intelligible than hieroglyphics. Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc., overboard from the Ship of Modernity.” The publisher gave half the space to Khlebnikov. He liberated words from their meanings and even indulged in prophecy. Viktor Shklovsky recalled a visual poem consisting of numbers: “The last line was: ‘Someone 1917.’ I met the fair-haired, quiet Khlebnikov, dressed in a black coat buttoned up to his neck, at some occasion or other. ‘The dates in the book,’ I said, ‘are the years when great empires fell. Do you think that our empire will fall in the year 1917?’ Khlebnikov replied almost without moving his lips, ‘You are the first man to understand what I meant.’”

Published six months later by Matyushin and Guro, the second edition of A Trap for Judges combined poetry and articles of literary criticism with illustrations. They were created – despite earlier conflicts – by representatives of Jack of Diamonds (Burliuk) and Donkey’s Tail (Goncharova, Malevich). As a result of a decision made by David Burliuk, in the next publication by the Hylaeans titled Sickly Moon, the group adopted the previously unwanted name imported from Italy by including the following subheading:

Almanac of the World’s Only Futurists!!!

The Hylaean Poets

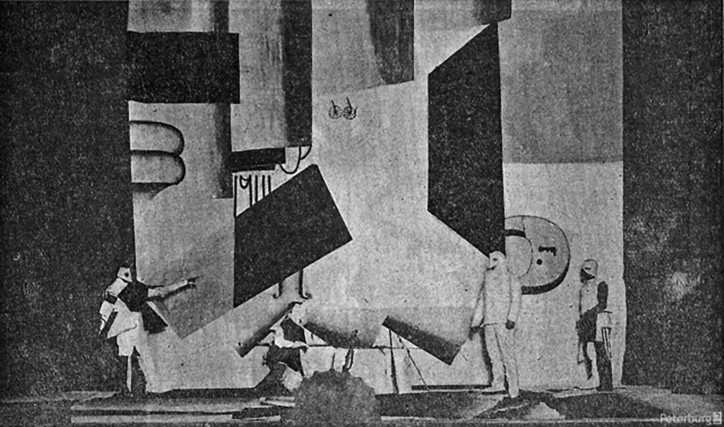

The group was constantly changing, and other names were floating around: Budetliane (a neologism invented by Khlebnikov from a future form of the Russian verb ‘to be’), and Cubo-Futurists (a term emphasizing the marriage of Futurist poetry and Cubist painting). The Budetliane strove for a synthesis of the arts. They became interested in theatre – an artistic sphere they hadn’t yet explored. Two plays they staged alternately turned out to be very successful; everything was accompanied by an atmosphere of constant scandal, and the police showed up at every performance. Although tickets were expensive, they sold out in no time. A tragedy written by Vladimir Mayakovsky was turned into a monodrama, despite the fact that the play was supposed to feature other characters. In his famous yellow shirt, Mayakovsky recited hypnotic poems exalting the role of the poet and fell into a demiurgic frenzy. The audience couldn’t tell if it was lyric poetry or a tragedy. The next day, the first Futurist opera, Victory over the Sun, was performed. Matyushin composed the music. The libretto was written by Kruchyonykh instead of Khlebnikov, who hadn’t made it from his native Astrakhan to Elena Guro’s dacha in Uusikirkko, where the play had been created. Khlebnikov had intended to go there, of course. He’d had enough money for the train ticket and had kept it clenched in his fist so he wouldn’t lose it. On his way to the station, however, he stopped at a bathhouse, jumped in the water and, unfortunately, opened his fingers.

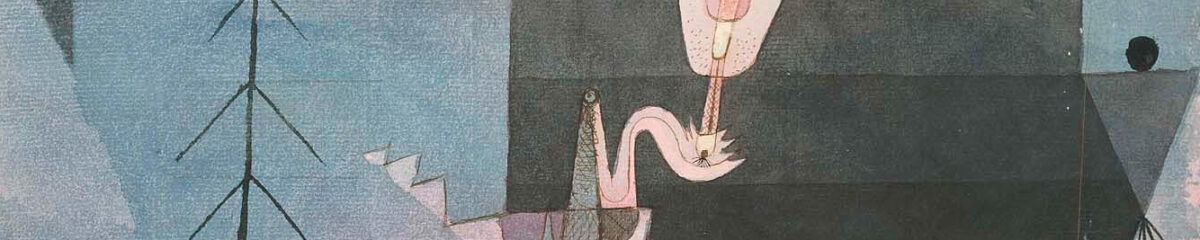

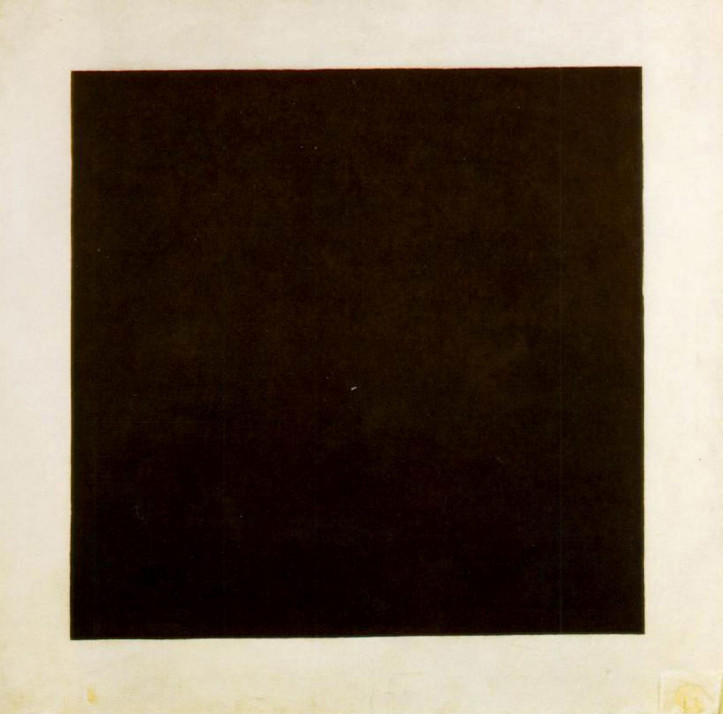

Kazimir Malevich’s set and lighting design was a true revelation. As he branched away from his early paintings filled with geometric depictions of the Russian countryside, Malevich gradually grew closer to Suprematism, which simplified everything to flat shapes and figures. His famous black square, which wouldn’t be exhibited in a gallery until the following year, had an unexpected onstage premiere. “The novelty and distinction of Malevich’s method lay primarily in the utilization of light to create form. This confirmed the existence of an object in space. […] These figures were cut up by the blades of lights and were deprived alternately of hands, legs, head, etc. because, for Malevich, they were merely geometric bodies subject not only to disintegration into their component parts, but also to total dissolution in painterly space. Abstract form was the only reality, a form which completely absorbed the entire Luciferian futility of the world. […] This was a zaum of painting, one which anticipated the ecstatic non-objectivity of Suprematism,” Livshits reported.

The Stray Dog Café and a sea of triviality

“War is the world’s only hygiene!” he exclaimed with all his remaining strength. “Long live militarism and patriotism! Down with the enervating influence of woman.” With these words, Filippo Marinetti ended his speech, to which the audience responded with applause that had the rhythm of a nationalistic drum. The misogyny of the leader of the Italian Futurists (completely blind to the role of outstanding female artists, a whole host of warrior women who were making breakthroughs in Russian art at that time) became very clear the following evening in a place that dissolved all ideological differences. At the Stray Dog Café, a literary and artistic establishment located in a cellar, a banquet was held in Marinetti’s honour. The Italian felt so comfortable there that the event became a nearly week-long celebration. Marinetti displayed doctrine in action. “Ten days before his arrival in Russia, he had published a manifesto titled Down with the tango and Parsifal! […] ‘Shove one knee between her thighs? How naive! And what is the other knee supposed to do?’ he addressed a petrified couple just getting ready to take up their positions. Overcome by such aphorisms, the most inveterate tango-dancers froze in their tracks. Triumphantly, Marinetti looked round on all sides and once more sank into his drowsy state.”

There was a caste system at the Stray Dog Café that divided people into artists and ‘pharmacists’ – the derogatory nickname for the rest of the crowd. The avant-garde artists experienced momentary victory there. Lawyers and members of the State Duma were eager to parade around in ridiculous paper caps that allowed them to enter the club on ‘special’ Saturdays – just so they could get closer to the muses and poets. One could brush shoulders with the poet Akhmatova in an elegant black dress or see Mayakovsky in the pose of a wounded gladiator, “reclined on a big drum, banging it every time the figure of a stray budetlianin appeared at the door.”

Outside, there was a “sea of provincial, consciously legalized triviality” in which Burliuk’s painted cheeks and Mayakovsky’s yellow shirt were forced to surrender to the waves of mocking glances cast from beneath top hats. The aim to make art the substance of everyday life – the ultimate ambition of this and every subsequent avant-garde movement – eventually had to yield to other revolutions.

Unless otherwise noted, quotations are taken from Benedikt Livshits’s book The One and a Half-Eyed Archer (English translation by John E. Bowlt: published by Palace Editions: St. Petersburg, 2004).

Translated from the Polish by Scotia Gilroy