In a 1957 article for “Przekrój”, former car mechanic and future sci-fi legend Stanisław Lem tried to assess the role of motorization in Polish society – and how it differed from the West in the first decade of communist rule. “Over there,” he noted, “the car is a practical object, something of primary need, roughly speaking, as shoes are for us.” But here in Poland, matters are different, he argued, noticing that the whole issue might be more suited to the musings of a psychoanalyst or a scholar of religion.

The days when a private car was obliged to hide beneath a rusty body are behind us. We no longer have to resort to mimicry by stripping off the paint and kicking the mudguards. Wartburgs no longer rivet the attention of dumbstruck natives – on the streets of Kraków and Warsaw, modestly waiting outside the houses, Warszawas are now appearing, Fiat-tiddlers (600s), Multiplas, on rare occasions Standards, Spartaks and Moskvitches, and from time to time a ZIM or some whale-sized hulk shipped in from abroad. The only thing that can still force the passers-by to kneel down and peek underneath is something with super-huge windows, the latest American model. So without much fuss we’re entering a new stage in Polish motorization. But we’re certainly not going to ape the West in a rigid, conventional way; here too we have our own special style, and we’re doing our catching up by following the Polish road – both metaphorically and literally.

The new cars have also done something to beef up the ranks of our heroic taxicabs. Their increasingly splendid appearance is opening our eyes to a curious sociological phenomenon – a problem from the realm of communications, namely the relationship between the taxi driver and his passenger.

Thanks to the lucrative nature of his profession, in Poland the taxi driver is a lord, a potentate on the way up, not just a colourless nonentity but a Somebody who can afford (at least) 100,000 złotys for a car [in 1957, the average salary in Poland was 1279 złotys per month, meaning that 100,000 złotys was the equivalent of 1.5 years’ worth of wages – ed. note]. He’s a Polish Rothschild, who by our standards has invested major capital in his business, so no wonder he doesn’t kowtow to his passengers, no wonder he’s not amused by nit-picking over the sum on the meter, no wonder he never has small change. You won’t find him at any of the less attractive stops or in areas that aren’t really convenient for him because he doesn’t drive when he doesn’t feel like it, and that’s that.

I’m not grousing or complaining – I’m just stating a fact, one that’s quite understandable from the economist’s point of view. As well as in the case of taxi drivers, we can see a similar sociological shift, a similar difference in proportion – compared with the West – among our private motorists.

Over there, the car is a practical object, something of primary need, roughly speaking, as shoes are for us. Thanks to the car (among other things), the prices of small houses and flats in the West are not as drastically dependent on how far they are from the city centre as here in Poland. You travel to work by car, and you go away for the weekend by car. It’s not just rich people who do that – though they often do things differently – it’s the average city dweller. On Saturday afternoons entire populations vacate the cities of northern, western or southern Europe, especially at warmer times of year, making the visitor think they’re ghost towns.

Of course there is a hierarchy among car owners that’s defined by wealth, and the dictates of fashion are a decisive factor. Even with negligible mileage, a car that’s a year out of date abruptly falls in price; a rich man has to have the latest car, with ‘eyelids’ on the headlights, a sloping bonnet, fully glazed bodywork – every year the fashion changes, and the slaves to their own, vast fortune have to obey it.

People of average wealth have cars like the Hillman or the Volkswagen, often models that are one, two or three years old. Finally, those whose desire to own a car far outweighs their money face a choice – whether to buy a larger car that’s a few years old, or a new but microscopic car, a motorcycle hybrid, often with three wheels, such as the Isetta, the Messerschmitt, or the slightly larger Goggomobil. Microcars are naturally more expensive than old cars – the two-seat Dixi made in (West) Germany about 20 years ago can cost 130-150 marks, but it is a thoroughly archaic creature, with its funny folding hood, large spoked wheels, angular, carriage-style body, standing out grotesquely from the small, modern cars, though in Poland of course it wouldn’t be quite so glaring. Its chief minus, if we leave out the shame of admitting to poverty by the mere fact of owning it, is its petrol-guzzling tendency. This is another reason for the great success and triumph of the microcars. So, broadly speaking, that’s how matters stand ‘over there’. Here, as we know, they’re different. In the first place, as far as prices are concerned, to all intents and purposes there aren’t any cars, old or new, from the year 1935 or 1955 available to those on the average or even a not-too-awful wage. Every car is ring-fenced by an astronomical price. That explains why in this country there’s no such thing as a range of prices corresponding to the actual difference in value of various cars; I have never heard of the most expensive car costing more than three times as much as the cheapest, whereas in the West the highest prices can be 12 times as much as the lowest (for instance, in West Germany a new, 1957 Ford costs well over 16,000 marks, which is over $4000, a new Opel costs more than 12,000 marks, a Goggomobil a little over 4000, and a used 1939 Taunus costs 1500 marks). So in Poland cars are a bit like coffee; throughout the world everyone knows there are better and worse kinds, floor sweepings and valuable, aromatic grains, whereas here coffee has one single price; coffee is coffee, full stop. It’s the same with cars – so here too the relationship between supply and demand plays a part; a more or less modern car, with ‘eyelids’ or without, costs pretty much the same. Up to a limit, of course – but the mere ‘aerodynamics’ of the vehicle, even if it’s 10 years old, guarantees its high price in excess of 100,000 złotys.

The rather negligible price differentiation in Poland, which causes a rise, and a significant one too, in the LOWEST prices and a relative DROP in the highest prices (according to the PKO’s conversion rates, a new Ford ought to cost 400,000 złotys here…) comes with an essential change in the function of the car in Poland compared with the West.

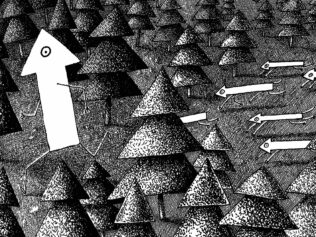

We can already tell by its price that it’s not a practical object here, but an extraordinary, total luxury. The first function of a car, and in fact EVERY car that’s privately owned in Poland is to dazzle, to spread your peacock’s tail, to stick a knife in the heart of everyone you know and slowly twist it.

Secondly, it’s for not travelling by tram or railway, for supplying yourself with ‘attractive items’, e.g. in Kraków – via drives to Nowa Huta – and for stocking up (and how: as you walk about town, do cast a passing glance at the cars standing outside the delicatessens or the Gallux stores).

Thirdly, it’s for outings. It’s quite exceptional to hear of anyone driving to work by car on a systematic basis, every day. And so the main function of the car in the West is not the most essential one here.

The oddity of ‘life with a car’ in Poland is complicated by many things – to mention just a few examples: the lack of good roads, the lack of service stations, trouble getting petrol or spare parts, or with finding a garage. Your private car is bound to consume a relatively large amount of time; you have to look after it, keep it in mind, often with fear (when it’s parked on the street), and so on and so forth. The height of chic, repaying all these inconveniences with interest, is to arrive by car at your summer holiday destination; hence the heavy density of ‘private traffic’ at the seaside and in the mountains, in Zakopane.

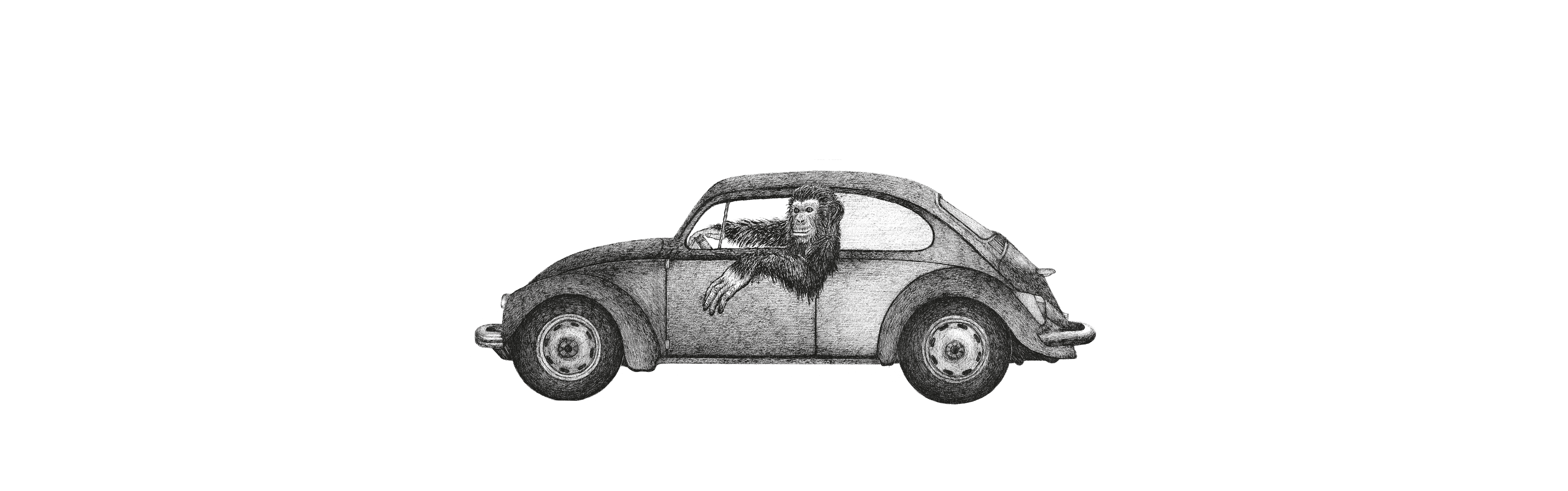

It really does seem to be chic that’s the deciding factor – the car is the object of a cult to a greater extent than an object with a function; it is not so much a means of getting from place to place as a miraculous device that transports its owner from among the grey crowd into the realm of the Refined Elite. The mere fact of owning a car affords sensual pleasure, as proved by watching the owners celebrating the Car Key, the Shammy Leather Cloth, Every Single Handle and Windscreen Wiper.

Even plainer displays of orgiastic intoxication are shown by those who don’t yet have a car but are expecting or close to their due date for delivery, with a car-purchase coupon pressing against their ribs. Proof that this is a mass phenomenon is provided by the fact that in the past few months every kind of car-driving manual has completely sold out. They have all vanished from the bookshops, even though there must have been far more of them than the number of Poles who can afford to buy a car.

The picture irresistibly presents itself of hordes of people hiding in their houses, poring over the chapter about changing gears and having a hard time controlling the twitch of a hand that yearns to touch a gear stick; in the face of this devastation inflicted on the national psyche by the car, when the driver’s manual has become a sort of Quran, the sacred gospel of a new faith, casually discussing the virtues and vices (mainly vices!) of a car in our circumstances, necessarily like pouring cold water over heads that are faint with desire, is plain indecency. For someone like me, who has spent time working as a motor mechanic, and is thus familiar with the anatomy of the car in a dry, business-like way, just as a gynaecologist is with the anatomy of the female body, the vehicle strip-tease performed at a garage doesn’t make his head spin or send shivers down his spine, so he feels awkward towards the car lovers who have blind faith in the automobile.

Because this is how things stand.

All the cars manufactured in the West are destined to drive on nothing but asphalt, just as everyone born in Europe is capable of living only within the sphere of civilization. Just as any townie would be bound to perish in a short space of time if forced to live in the jungle, so the car constructed with motorways in mind finds itself facing mortal danger if cast into a roadless wasteland.

It’s worst of all for the cheapest cars. Vehicles like the Messerschmitt, for example, are totally unfit for use on anything but asphalt. The Messerschmitt, a funny car in which two people sit under a plastic hood ‘in single file’, one behind the other, is a three-wheeler that can reach a top speed of 110 kilometres per hour (I have checked). However, even on an entirely smooth surface before reaching 90 it starts to shudder down its longitudinal axis, jumping about like an agitated grasshopper for lack of stability. Of course, if the front wheel of a car like that were to fall into a pothole, it would probably stay in it; naturally the car would turn head over heels. There’s a similar danger facing all cars with small wheels. The more uneven the road, the smaller the wheels, and the smaller the weight of the entire car in relation to the weight of the sprung chassis, the worse it is.

So in Poland, the cheapest little cars, as they’re also the weakest, are fit only for driving on asphalt, though we don’t actually have much of it. Any sideways jumps, any straying off the beaten path is soon going to cost the microcar owner a high and painful price.

Hence the unhappy conclusion that what we need are larger, stronger cars. They should probably be relatively simply constructed too, and not too sensitive to low-octane petrol that’s not of the highest quality. To say it like a man, the ideal car for ALL Polish roads would be a vehicle that was built with potholes in mind, and that means the Ford Model T from 35 years ago, an enormous, ancient vehicle…

In Poland, any newer American car is doomed either to imprisonment on nothing but the limited range of the few good national highways, or to fairly rapid ruin, which as an ominous memento mori will be accompanied by the constant hammering of the silencer against stones on the road…

But, of course, all these Cassandra-like claims and pessimistic warnings lose their power when what a person desires is merely to OWN a car, not to drive it into any wasteland, rarely to drive it at all, and never to go beyond a first-class road.

That’s how the vast majority of homegrown car owners seem to proceed, as far as I can tell. The exception is a handful of impassioned, ‘rabid’ adventurers, descended from the Chevaux-légers at the Battle of Somosierra [Poland’s equivalent of the Charge of the Light Brigade – trans. note], who slaughter their little Fiats or Wartburgs without much mercy on wild, sandy, field roads.

But if the car is not meant to serve as a means of locomotion from any randomly chosen spot in the country to any other, an issue to do with transport and motorization changes into one that’s beyond economic values, and moves into the obscure realm of Mystical Thrills, Irrational Feelings, Passions and Desires, in short, into the sphere of controlling the Subconscious, Wanting to Show Off, to Satisfy Your Cravings – and in the process it starts to be more suited to the musings of a psychoanalyst or a scholar of religion than those of the former car mechanic that I hoped – exclusively – to be in these comments… All the more since I haven’t even tried to touch on the most mysterious, enigmatic issue of all, one that lies safely within the territory of Supernatural Occurrences and Miracles, which is the question of having the means to buy a car. Here the psychoanalyst would probably have to be replaced by a demonologist, or in many cases a criminologist. But that really is a completely different matter.

This article is from issue 645, published in 1957.

Translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones