The Seventh Continent keeps on growing. It feeds on plastic waste dumped by all the people who live on the other six. Will it take over the entire world, turning into a new Pangea – no longer the seventh, but the only continent, made of plastic? So far, it has reached Turkey and become the focus guest of the big fat 16th Istanbul Biennial.

Mornings in Istanbul are epic; the sun shines through thick layers of smog, lending the light surreal hues. You don’t need to set an alarm in order to see this spectacle; the streets of the Beyoğlu district in the city centre are clogged already before dawn and stay this way until late at night. The noise of engines and horns makes the pollution dust tremble in the air.

No wonder the Biennial opens with a piece made from smog, no less. Croatian artist Dora Budor encapsulated polluted air in large glass containers, before adding dramatic lights, making the dust dance to the rhythm of the vibrations transmitted from the building sites nearby. How beautiful they look, those clouds of colourful chemical mist. Nicolas Bourriaud, the exhibition curator, notes how the installation brings to mind the eerie atmosphere of William Turner’s paintings. The English painter, known as the precursor of impressionism, left his mark on the pages of art history as the first artist who painted smog back in the 19th century, when the industrial era was still young. Bourriaud suggests that we see Turner as the father of Anthropocenic art, stemming out of the new geological era that holds humans at its centre, albeit not necessarily in a good way. In this way, the participants of the Biennial – all the artists invited here to consider what humans have done to the world – are William Turner’s children.

The last time I visited the Istanbul Biennial was in 2013, when the exhibition took place in the shadow of protests and riots. It all started with the public blockade preventing the cutting of trees in Gezi Park, a patch of green in the heart of the city, near Taksim Square. The conflict ended with a clash of the liberal, secular Turkey against the increasingly conservative and authoritarian rule of President Erdoğan; it was a conflict that lasted for a month. During that time, it was hard to cross Taksim Square without crying; the air was thick with tear gas. Preventive police troops were hiding in the streets connecting with İstiklal Boulevard, ready to intervene should any activist try recommencing the riots.

This year, the Istanbul Biennial is taking place in a city freshly retaken by the opposition from the hands of the governing party after a sensational municipal election. Loss of power over the capital is the first acute failure of Erdoğan’s crew after two decades of uninterrupted triumphs. Commentators view it as a harbinger of the beginning of the end for Erdoğan, who is commonly known as “the Sultan”. Erdoğan, however, is far from surrendering – in fact, he is banking on the opposite solution. After all, winning a war seems by far the best remedy to the power crisis, and a great way of distracting the citizens from rampant corruption and swelling economic problems. And so on 9th October, the Turkish army launched an offensive into north-eastern Syria, the world was taken aback, and an Iranian artist I’m friends with sent me an angry post, dissing me for the very idea of going to Istanbul in such a situation. She believed that in this political climate, the Biennial should be boycotted. Meanwhile, Erdoğan’s support kept on growing; the Turks were conflicted between the increasing weariness of the Sultan’s rule and the spectacle that stirred their patriotic feelings. Whatever you want to say about Erdoğan, you can’t deny he is a true virtuoso when it comes to playing those strings.

And how does art respond to this whole situation? It is, after all, so incredibly sensitive to political contexts. “If you want to ask me how does one measure the power of a society, I shall say that culture and art are at the top of my list. When we look at the nations we consider global superpowers, the first thing we notice is their culture and their art,” said the president recently during the official opening of the Odunpazarı Modern Museum in Eskişehir, 200 kilometres away from the capital. Futuristic Japanese design, boldly inserted in the landscape of Ottoman architecture by the prestigious Kengo Kuma Studio; an impressive international programme; star-studded exhibitions, big money. In Poland, we can but dream of such institutions. In Turkey, however, there are plenty of those, especially in Istanbul. The capital is abuzz with work; everyone’s eyes are on the giant building site where the new building of Istanbul Modern is being constructed. The edifice has been designed by none other than Renzo Piano, the co-author of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Global-scale artistic life in the capital is funded with private money. Among the richest Turks, there are countless art lovers, such as the developer, real estate investor, and collector Erol Tabanca, who sponsored the Odunpazarı Museum. Collections and private museums are usually paid for with old money – fortunes of the families who made their wealth back in the interwar period, on the wave of the modernizing endeavours of Atatürk, the father of modern Turkey. Those well-educated, cultured elites and long-standing patrons of the arts are, of course, very liberal. They love new ideas and the contemporary art that brings them. Erdoğan, with his praise of religious values and remaining in conflict with the Western lifestyle (especially the idea of civil liberties), doesn’t stop the moguls from expanding their artistic fascinations. Tradition may be necessary, but the nation’s creative life should reflect the global ambitions of a country with a penchant for imperialism. Of course, artistic liberties are not limitless. During the Odunpazarı opening, Erdoğan did not stop with a speech. The president also reached for a brush, stood by the canvas and beautifully calligraphed the Arabic letter wāw. What could be done? The piece had to be placed in a spot of honour. Many artists were dismayed, but among those who risked open criticism, most were no longer living in the country. Back home, they would have had to watch their words. The number of jailed journalists who have dared to criticize the government here is the largest in the world, per capita. Among those arrested is Osman Kavala, a philanthropist and the president of Depo Gallery – an independent arts institution founded a decade ago in a former tobacco warehouse in the Tophane quarter. Kavala’s case illustrates well what happens to those unwilling to respect the unspoken but unbending rules that govern public debate in this country. Kavala kept crossing those lines and ended up charged with an attempted coup.

In this political climate, is it really a surprise that the Istanbul Biennial is turning its gaze towards the seventh continent and, simultaneously, away from the events taking place in Rojava or in the black holes that hold political prisoners? The power behind this event is Koç Holding, a conglomerate that belongs to the richest family in Turkey. The Koç clan is the most powerful player in the Turkish art world; the founder of many privates museums and collections, and a generous exhibition sponsor. And every two years, it gives the people of Istanbul a lush biennial on the highest international level, planned by the stars of the world curatorial industry. Entry is always free. However, art is just the tip of the iceberg of the group’s operations. Its tentacles reach pretty much everywhere, from finance and real estate investments, through food production, all the way to weaponry. And a substantial part of their business is done with the state. One must find a way to co-exist with the government, whatever the weather.

Those who expect art to touch on such issues as freedom of speech, the situation in Syria, or, God forbid, Kurds, need to look for another biennial. The one in Istanbul was prepared by Nicolas Bourriaud, a sophisticated French intellectual who came up with the concept of relational aesthetics that took the art world by storm. He is the co-creator of Palais de Tokyo in Paris, former director of Beaux-Arts, and currently the director of the Contemporary Art Center of Montpellier. Bourriaud is a superstar who’s been around and seen his fair share, from Taiwan to Moscow. He knows how to work in countries that may very well have some form of democracy going on, but of a more ‘sovereign’ or ‘illiberal’ kind. The guy knows how to prepare an exhibition that will be good while not having the local string-pullers foaming at the mouth. Upon his visit to Istanbul, the diplomatic curator chose to criticize humanity as a whole rather than focusing solely on disapproving of the local government. And his intentions are not unfounded; after all, nobody’s hands are clean. Let’s not push all the blame onto the Erdoğans of this world.

The titular seventh continent, for example, is a product of our collective efforts. It is the size of five Turkeys and was made from millions of tonnes of the plastic waste drifting on the North Pacific. That is the true anti-Atlantis worthy of the Anthropocenic era. It is an island that refuses to sink, looming taller and clearer instead, growing in front of our very eyes. Bourriaud has turned this giant lump of trash into an expressive metaphor. In his narrative, the seventh continent is a dark doppelgänger of the New World; of the promised land awaiting us somewhere over the sea, ready to be discovered, conquered and colonized. Except nobody is keen on conquering the seventh continent, as it’s made out of trash. Its body consists of everything our civilization has rejected and repressed.

However, psychoanalysis shows us that repressed content will, sooner or later, float back to the surface of our consciousness, just like waste bobs on the ocean waters. We don’t even have to go to the Pacific Ocean anymore in order to visit the seventh continent; it’s knocking on our door already. The Istanbul Biennial is the best example of this process. The event was initially supposed to take place in the spectacular scenery of the Haliç Shipyards on the Golden Horn. Just a month before the opening, it transpired that the whole area is polluted with asbestos to such level that it was impossible to let any visitors inside. The great exhibition had to be moved last-minute to the unfinished Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture that is emerging at the Fine Arts University in Tophane. During the opening ceremony, Bourriaud pointed out – not without some perverse pride – that his exhibition was the first art biennial to be evacuated for an ecological reason. And who’s to say that his project is detached from reality now?

The Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture is still unfinished, but it’s already set to be a spectacular place; another super modern institution in the capital. But considering the looming catastrophe, do we really need even more art? What can artists do when faced with a real crisis?

In the first part if his exhibition, Bourriaud shows us a panorama of the Anthropocenic world. In her video installation, Eloise Hawser takes us to the largest waste sorting plants in Turkey, which look like the backdrop to a cyberpunk dystopia where enormous robots eat through endless mounds of waste in an effort to segregate it for recycling. This fight seems to be lost from the start, and the artist further illustrates her videos with several sculptures that she made out of recycled waste. Her works are beautiful, but they seem to be steeped in melancholia. If we wanted to repurpose the seventh continent this way, half of the world’s population would have to abandon their current occupations and dedicate their lives to making recycled artwork.

The Feral Atlas Collective consists of nearly a hundred artists and scientists studying the new ecosystems of the Anthropocene. The results of their research, presented in the form of videos, installations and drawings, lead us to two conclusions: a good one and a bad one. The good one is that nature can survive anything; it can handle even a seventh continent made out of plastic. The world will not end; it will just be different from the one we knew. The bad news is that in this new world, there may no longer be a place for humans, who will fail to handle the situation in which they have put nature.

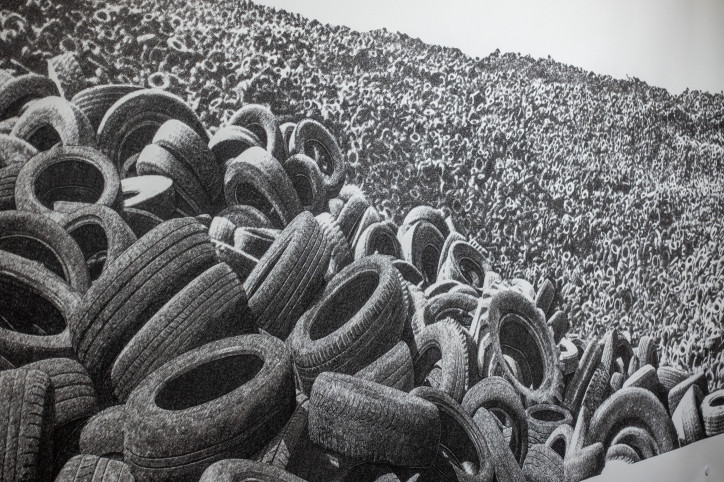

Deniz Aktaş presents hyperrealistic drawings of piles of tyres at landfills. Ozan Atalan gave up on making a sculpture, and instead presents the skeleton of a water buffalo, one of the countless victims of the rapid development of Istanbul that expands onto further ecosystems not long ago inhabited by wild animals. Polish artist Agnieszka Kurant presents ‘fordite’ – a new mineral unknown to nature, often found near large automotive production lines. It’s a human-made, post-industrial, semi-precious stone made of fossilized car paint. Is it of any consolation that among the many layers of Anthropocenic waste there will be some bits and pieces that could be regarded as beautiful in their own way? Luckily, that’s not the only answer Bourriaud has for us. The exhibition moves discreetly from the haunting landscape of skeletons, industrial fossils and invasive plastic-feeding species, to works made by artists looking for some new paradigms; for a new language to once again retell the relationship between humans and the world, between the human and the inhuman. The speech of modernity is unable to express this new thought. Modernity was great in colonizing the world; we excelled in exploiting humans, animals and resources. However, now it seems that in following this path we will get nowhere but to a seventh continent made of waste. Bourriaud shows us the works of artists who reinterpret the discourses of some cultures outside of Europe, seeking solutions in old and new rituals, in shamanic and techno-shamanic rites. Magic? Why not, what do we have to lose? French artist Suzanne Husky invites us for a seance with Starhawk – a feminist, writer, witch, and the pagan priestess of an earth cult. In a darkened room, Starhawk’s image emerges in a video projection; the witch is playing a drum while reciting a song about growth, death and regeneration. This spiritual leader sure does have a lot of charisma. When she tells us to breathe in and out, I catch myself following Starhawk’s instructions without even thinking about it. I’m not the only one; my neighbours gathered in the room also begin their rhythmic puffing. When we leave, we feel confused. Did this seance bring us closer to being at one with the earth and the world, or was it just another new age-y illusion in the vein of a meeting with Anatoly Kashpirovsky, just a notch better, because it was wrapped in artsy tinfoil?

Bourriaud leaves us with an unanswered question, as this part of the exhibition also comes to an end. The rest of the Biennial requires us to move from the unfinished building of the Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture to the centremost part of the city. There, in the Pera Museum (yet another institution that belongs to Koç Holding), the curator replaces the catastrophists, shamans, ecologists and witches with artists who now are more like anthropologists or archaeologists. The cultures studied by these researchers turn out to be fictional ones; their exotic gods are made up, and their archaeological artefacts are fabricated. Some of the fictional realities are utterly fascinating, such as Charles Avery’s project. The artist turned one of the representative exhibition rooms into a fish market with baskets full of glass eels and seafood that look monstrous and appetizing all at once (shame they’re just sculptures), alongside some unnamed, unexplained creatures. This scenography and menagerie all come from the Island, a made-up land that the artist has been creating and presenting for over a decade. Drawings, maps, genre scenes, everything to expand the idea and mythology of this fictional place, hanging halfway between post-tech dystopia and a utopia built on the ruins of today’s world.

Even more interesting is the case of Norman Daly. This American artist, born in 1911, had begun his art project in the 1970s. This monumental endeavour was dedicated to unearthing the forgotten civilization of Llhuros. There was never such a civilization, and yet, thanks to Daly, we have hundreds of artefacts to prove its existence: sculptures, jewellery, weapons, cult objects, and things of still-unknown purpose. On top of that, we get plenty of photographs showing the ruins of Llhurosian buildings, along with documents, archaeological analysis, and interpretations. Daly passed away in 2009; he had spent the last four decades of his life fully committed to creating his lost civilization. At the Biennial, we get just a glimpse of this magnificent and insane creation, very Borgesian in spirit. Any sceptical viewer will quickly notice that the ancient ‘findings’ from Llhyuros (ritual masks, spears, funerary steles) have been made out of rusty scrap metal, car parts and trash that could be found at the landfill – literally, as the artist often went there to harvest materials for his project. But were Daly’s fantasies really so far off from our ideas about the past that we indulge when building our identity on scraps of mythologized history, made to serve politics? In Poland, we understand the problems of historical politics all too well. After all, in this department we are quite like the Turks, who also like to intoxicate themselves with memories of their glorious past. The most interesting question asked by Daly’s madman project is the one that refers to the future. Before, we used to imagine the future as an era of humans conquering Space and colonizing it, just like we had colonized our own planet. But isn’t this idea more likely? The one where some future archaeologists unearth bits and pieces of another ‘lost civilization’?

With this sombre thought on my mind, I get on the ferry that comes from under the fisherman-plagued Galata Bridge. Bourriaud decided to finish off his biennial at one of the Princes’ Islands on the Sea of Marmara. Well, let’s go to the island! How very apt; how fitting with the theme of this whole exhibition.

On the way, the sea breeze carries away all my dark thoughts about the monstrous stains of death and the remains of our civilization, to be unearthed one day from the (hopefully not radioactive) sand. Finally, the yellow smog of Istanbul is gone. The inhabitants of this monstrous city are now leaving. The buffet area is crowded beyond help. Young men smoke illicit cigarettes on board, and some girls from deep Anatolia sing folk songs, collecting change in an upside-down drum. It looks like they made quite a bit of money today.

I’ve seen it all before, at the same event. Back in 2015, the curator of the 14th edition of the Biennial, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, also stretched the exhibition all the way to the Princes’ Islands. In the Byzantine times, they were used as a place of exile for inconvenient princes and princesses – that’s where the name of the archipelago comes from. The Ottoman emperors continued this tradition until its morbid finale. In the 20th century, moving the members of the royal family had become a thing of the past, so princes and princesses on the island were replaced by dogs. In 1911, the administration of Constantinople came up with the idea of catching all the homeless animals wandering the streets of the capital and sending them to the island of Sivriada. Over 80,000 dogs were sent to this waterless, deserted patch of land. The animals died of thirst, ate one another, and drowned when trying and failing to leave this hell. The wind carried the stench of rotting canine corpses all the way to the capital; some say people could even hear the howls of dying dogs. When the agony ended, the city was plagued with an earthquake, which was broadly considered punishment for the canine holocaust. When Christov-Bakargiev took her exhibition guests to Sivriada, she suggested the torment of dogs could be read as a bad omen, foreshadowing the genocide of Armenians that began only four years later, in 1915.

Our ferry passes by the grim island of dead dogs and reaches port in Büyükada. Were they sending people here? Not the worst place for an exile; it looks like a Mediterranean paradise. Here, there are almost none of the cars that torment Istanbul with never-ending traffic, plumes of exhaust smoke and the clamour of horns. Instead, there is plenty of greenery, so sorely missed in the capital. And all this awaits just an hour and a half away from the overpopulated city centre. According to official records, Istanbul has 16 million inhabitants, but in reality, the numbers are much higher, especially since the influx of illegal Syrian refugees, many of whom have become homeless, rummaging in restaurant bins in the tourist district in search of food. There is no way of leaving this town on land; you can keep driving out of the city centre for hours, and the metropolis will keep going, seemingly forever.

No wonder Büyükada is one of the places favoured by the city centre dwellers as a weekend getaway destination. The rich have their suburban homes here – the most beautiful are the marvellous wooden villas from the early 20th century. The oriental Art Nouveau buildings sit among magnolias, lemon and fig trees. During the Biennial, we can enter some of these estates. In one of them, American artist Glenn Ligon presents an exhibition centred around James Baldwin – the African-American writer who is also an emblem of the fight for black people’s civil rights, and an important figure in the movement for the emancipation of non-heteronormative people. Baldwin spent most of his life in voluntary exile from the US, travelled the world, and in the 1960s, stayed in Istanbul for a longer time. Ligon brilliantly enmeshed this character – a black gay writer, a stranger in a strange city – with the guiding principle of Bourriaud’s biennial. If there is any hope left for us at all, it lies in overcoming the very concept of otherness, transgressing the division of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. And it’s no longer (like it was in the times of Baldwin) the Others who are defined by their race, sexuality or nationality. Now, it’s also about ‘us’ and the ‘world’ that we have, for too long perceived as one great Other. We must realize that we are not the masters, owners or users of the world, but just a part of it. Otherwise, we will all end up in the seventh continent.

*

16th Istanbul Biennial: The Seventh Continent

Curator: Nicolas Bourriaud

Until 10th November

www.bienal.iksv.org

Translated by Aga Zano