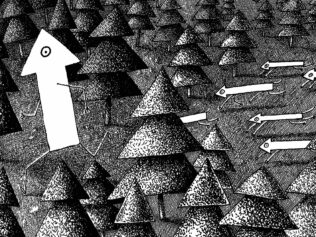

In the heavy, post-war atmosphere a magazine was born, created from humour, absurdity, lightness and colour. “Przekrój” was a phenomenon. It was unlike anything else; set sideways to the course of the regime and operating in technical poverty. It was quite simply an impossibility. And yet there it was, and everyone read it, from the back to the front.

The war was still on when the first issue in April 1945. An accident had helped. On a street in Łódź, Jerzy Borejsza, the head of a growing publishing empire called Czytelnik, bumped into Marian Eile. They knew each other from before the war when Eile had been secretary of the Wiadomości Literackie [Literary News]. Borejsza was looking for people to create a weekly illustrated supplement. Eile hopped into a little crop sprayer plane and flew as fast as he could down to Kraków, where priceless technical and intellectual materials were stored: printing presses that still worked and, living one above the other in the same tenement block, a group of writers and artists who had survived the wartime conflagration. Jerzy Putrament – who was meant to be the editor-in-chief – had the misfortune of being shot. During his recovery, he simply said to Eile: “Take my place.” So Eile took over – for the next 24 years and 1277 weekly issues of “Przekrój”, without which, for many, life under socialism would have been unbearable. Years later, Agnieszka Osiecka wrote that “Przekrój” “was a lesson in laughter, tact and sensitivity. ‘Przekrój’ had created something which de facto didn’t exist: the illusive literary salon.” Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, who wrote for the weekly for many years and who was the author of the column Teatrzyk Zielona Gęś [Green Goose Theatre], put it more succinctly, inventing the notion of ‘“Przekrój” civilization’.

“Przekrój”’s spark

“Lightly; the magazine should have a light touch,” believed Eile, a permanently dissatisfied perfectionist. He was the ideal editor, who always spotted unnecessary words in a text and came up with the best titles. He was a skilled draughtsman and someone who liked to see everything through to the end. He was charismatic and very personable in private but, at work, he was demanding and sometimes brusque. He knew how to inspire, but also how to say no. To outstanding writers, who he would go on to employ for years, he would say grudgingly: “Well, stay for a trial period. One week…” He rarely gave praise. In his Paris days, he had soaked up refinement and style. He was popular with the ladies, yet often dressed scruffily, wandering about in trodden down slippers. He smoked like a chimney and had piles of books, magazines, press cuttings and notes stacked precariously on his desk. He disliked tidy desks; for him the mess was proof of life. This may be the origin of “Przekrój”’s unusual, almost intentionally overcrowded and rather chaotic visual style. All those ideas and intellectual diamonds crammed into just 16 pages.

Even as a child, Eile had put together home-made illustrated newsletters and, for 25 years, he had enormous fun assembling “Przekrój” from different bits and pieces, aesthetic and intellectual sparks, and intertwining articles on important or compulsory topics. Operating under the reality of political repression and censorship, he managed to bring together a team of talented eccentrics and to effectively convince the authorities that they were only fooling around, creating a little magazine in a childish fashion. “Przekrój” was a brilliant stunt: thumbing its nose at the oppressive reality, while at the same time being the highest form of art; an innovative, bold, artistic-literary creation; the incarnation of humour and imagination.

“Przekrój”’s genius

So how did “Przekrój” escape the restrictions while remaining in the limelight? Because, just as Eile had intended, absolutely everyone read it; “whether they were refined cleaners or simple government ministers.” Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz is alleged to have spotted his future wife on the cover of “Przekrój” – the phenomenal actress Nina Andrycz. And it was “Przekrój” that the hero of Andrzej Wajda’s cult film Innocent Sorcerers was reading. This character was a doctor, boxer and jazzman; in a word, an individualist and an undesirable under socialism. Workers travelled to work with a copy of “Przekrój” tucked under their arm and everyone obediently started to read from the last page first, printed sideways – both physically and metaphorically. The ‘back-page’ of the weekly was put together by the poet and satirist Ludwik Jerzy Kern. It contained cartoons, jokes, playful posters, little poems and short news. This turning one’s back on reality took two aspects. First, the magazine’s editorial team approached everything differently, in their own way. Second, the front of the publication – its first few pages – were reserved for political articles and compulsory topics; in other words, what Eile called the ‘offering’ to the authorities and the press censors. At the front, “Przekrój” had what it had to have, but at the back it had what it wanted. This strategy of avoidance and diversion was Eile’s personal choice, since he was not interested in politics and did not want any open confrontation. He was, apart from Jerzy Turowicz of Tygodnik Powszechny (a Roman Catholic weekly), the only apolitical editor-in-chief in the People’s Republic of Poland.

Although there were different opinions about this approach, he undoubtedly provided a platform for every significant writer and poet of post-war Poland on which to display their talents, including a number of geniuses. Those published in “Przekrój” included: Gałczyński, Iwaszkiewicz, Broniewski, Nałkowska, Tyrmand, Tuwim, Wiech, Lem, Miłosz… In 1950, Sławomir Mrożek made his debut in “Przekrój”, and international luminaries were reprinted and discovered by many readers for the first time; authors such as Kafka, Borges, Nabokov, Dickens and Hugo. Each week, a window onto the world was opened for the Polish people living behind the Iron Curtain. And what came in through that window was absorbed with delight and with trust. “Przekrój” effectively shaped the knowledge, tastes, fashions, lifestyle, language and daily culture of a society that was confused and lost after the war, and going through dramatic changes. For Eile, the readers were the priority. He had professional intuition and the ability to understand readers’ collective needs and emotions, even before they expressed themselves in the public mood or behaviour. He could anticipate what people would want next. Thanks to this talent, he made “Przekrój” rather like setting the latest fashions – the magazine was always one step ahead.

“Przekrój”’s garb

Of course, Eile wasn’t working alone on this ambitious undertaking. The talents of all the permanent and ad hoc contributors to the magazine helped to build the “Przekrój” civilization; above all, Janina Ipohorska, whom the editor knew from their hometown Lwów (present-day Lviv in Ukraine), with whom he had an understanding like no other, and from whom he was inseparable over several decades. Married to Krystyna and tied to Janina through his passion, he would say: “I have two wives.” Ipohorska is said to have paid for this three-way arrangement with suffering and a breakdown, but she was the only one in the editorial team with skills comparable to Eile. She remained in his shadow; only members of the editorial team recognized her enormous influence on the magazine. Ipohorska and Eile were the only ones who single-handedly knew how to produce a magazine that demanded such imagination and sparkle. Just like the editor-in-chief, Ipohorska could draw, edit and layout, was able to make up and invent headings, titles and slogans, and last but not least, knew what to give the readers. It was she who, over the years, created the inestimable school of decency and good manners, writing the Democratic savoir-vivre column – a warm, humorous and unpretentious manual for how to behave in doubtful circumstances. After the devastation of the old world order through war and the establishment of the new order, these guidelines, full of sincerity and flair, were much needed, written as they were in response to the sacks of letters that flooded into the editorial office from people who wanted to live their lives a little better, more pleasantly and more wisely.

Ipohorska also brought other talented people to the team, including Barbara Hoff, who, through “Przekrój”’s fashion section, went on to dress all of Poland – on trend, sophisticated and inexpensively. Visiting Paris regularly, Eile took fashion seriously, as a meaningful part of culture, and he made space in the magazine each week, not just for practical fashion tips, but also for theoretical discussion of the subject. For the Poles, deprived of foreign influences and styles, Hoff was an oracle and a good fairy, as well as giving practical training and teaching people how to bring a little magic into their prosaic world. In the mid-1950s, she gave Polish citizens, from the Tatra mountains along the length of the Vistula River to the sea, instructions on how to make their own trumniaki (coffin-shoes – a reference to the cardboard shoes that undertakers wore during funerals during the communist era in Poland). In other words, she showed people how to convert old white gym shoes into smart black shoes, by cutting and painting them so smartly that you could almost imagine that you were walking down the Champs Élysées. She taught how to turn sports blouses into sensual leotards, and how to make smart trousers out of plain cotton drill: how to wear whatever was available to buy, but elegantly; how to keep with the zeitgeist in rough circumstances that were hostile to spontaneity or change. The designer had an endless supply of ideas, and the streets would swarm instantly with living practical examples of her tips and advice. Hoff was also a language trendsetter, and we have her to thank for words like wdzianko (‘garb’) and the Polonized dźinsy (‘jeans’). Moreover, as one of the first people in the country ever to sport American denims, she created a big stir with them during a jazz festival in Sopot.

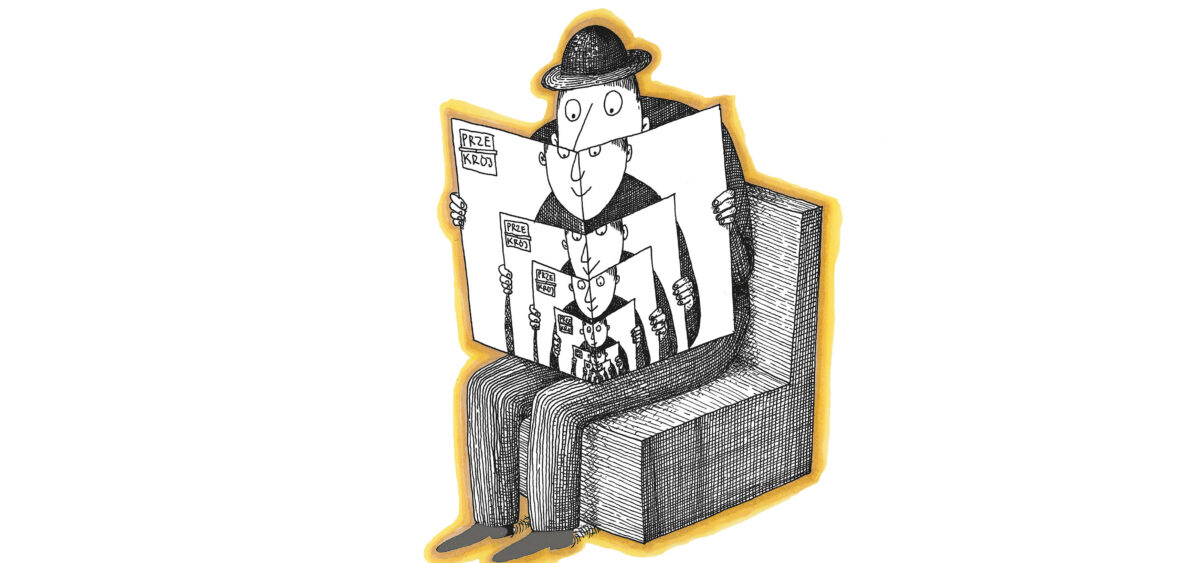

During its golden quarter of a century, “Przekrój” had several dozen such personalities who, with their good taste and perception of the world, exerted a fundamental influence on the character of the magazine and those around it. These included cartoonists. Zbigniew Lengren gave the Poles the character Filutek, a professor always drawn in profile. Filutek is an amusing man in old-fashioned clothes with an umbrella and bowler hat, who went through every imaginable kind of adventure that Lengren – himself funny, but never cruel, not prone to boasting nor to being conformist – could conceive of.

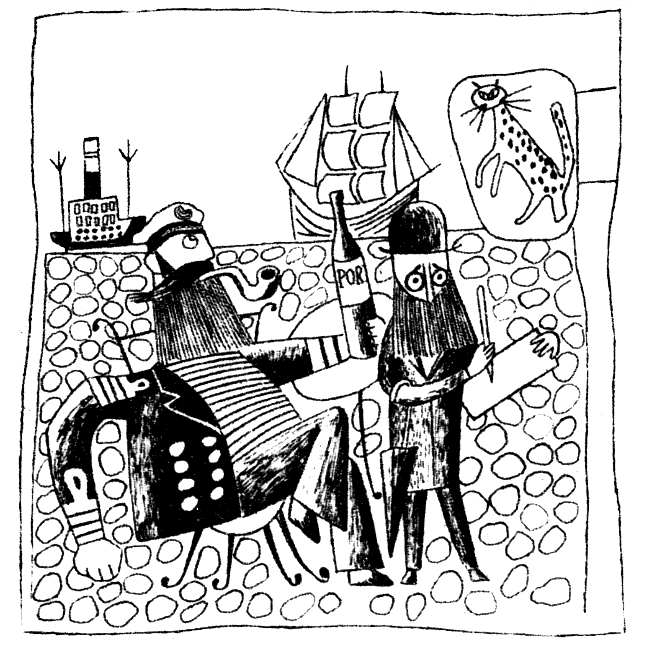

Daniel Mróz helped to refocus the design of the magazine away from the aesthetics of collage – favoured by the authorities – towards cartoons and illustrations, which skilfully positioned “Przekrój” a little out of time, outside the mainstream and beyond any cliché. The magazine used and added colour to photographs, but usually with the addition of annotations by the author, whether drawn elements, speech bubbles or additional little details stuck on. No-one worried about intellectual property rights (an unknown concept at the time in Poland), so it sometimes happened that the illustrations were made up as a visual combination of cuttings from other magazines imported by Eile and Ipohorska in suitcases from France. When staying there, they survived on instant coffee and buns, but spent copiously on records, magazines and books.

It was only at the end of the 1950s that Wojciech Plewiński became “Przekrój”’s first full-time photographer and, at the same time, creator of another of the magazine’s iconic elements – a series of ‘kitten’ covers. The instructions were clear: a pretty girl on the cover sells the whole print run. She should be blonde and very young. This first requirement had some technical merit, since dark printing ink would smudge and risked leaving a dark stain across the model’s head. Putting together the front cover was a near impossible task. Once a week Plewiński, with the invaluable assistance of Barbara Hoff, ‘produced’ a photo shoot with a girl: a complete amateur, spotted somewhere in a corridor of the Academy of Fine Arts, or at a cinema, or on a beach (as wth Beata Tyszkiewicz), or simply on the street (as with Anna Dymna). The girls blagged clothes off friends, and Hoff helped put together a stylish outfit from whatever they had. With make-up and hairstyling for this cottage production and Plewiński’s talent, the cult of “Przekrój”’s cover page was launched, along with the careers of many girls, like Edyta Wojtczak, who went on to become the darling presenter of national TV, then still in black and white.

“Przekrój”’s poverty

Leopold Tyrmand wrote, rather harshly, of “Przekrój”: “A group of cynics who, by avoiding a clash with the regime, make a comfortable life for themselves by imitating Western aesthetics.” Despite this, the creators of the magazine knew no particular comfort, nor did they bask in fame. Eile never signed his drawings, while Ipohorska used a pseudonym for many of her columns and texts. In fact, it is said that all members of the editorial team used pseudonyms as they worked intensively on all fronts, because Eile wanted to create the impression of variety. He didn’t want recurring names under the articles. The editorial team earned little, i.e. more or less what people earned in similar positions elsewhere. Eile, it is true, was crazy about jazz and cars, but he always spent within his means. When he came across an automotive bargain at the seaside – a Fiat 600 – he bought it for a song along with numerous dents in the bodywork and… no key. The editor spent his later years in a small apartment-workshop – more like a student digs – and that’s where he died. No-one made their fortune working on the world-class “Przekrój”, because it was the dream and adventure of a handful of people; created from scratch each week in a 60-metre apartment and in several dozen extraordinary minds that were able to push the boundaries of what was permissible. The creative force of these exceptional people was the fuel and foundation of this cultural phenomenon. “Przekrój” never become a machine. Each issue was invented anew and every column designed without a fixed format. It was built from whatever the authors brought to the table.

“Przekrój”’s dusk

In 1968, after the ‘March events’ [the suppression of anti-communist student and dissident demonstrations – ed. note] and an ongoing anti-Semitic campaign, Marian Eile concluded that the authorities would not allow him, with his Jewish heritage, to run the magazine any longer. He left for Paris on a passport valid for two years, although formally he remained editor-in-chief until October 1970.

According to his biographers, Eile had lost his enthusiasm some years earlier, deriving dwindling pleasure from creating the magazine. He sent his resignation letter from Paris, and when he later returned to Poland it was not for the magazine, nor for his wife, nor for Ipohorska. It was the latter who suffered the most; she waited months for Eile to return. She came to work like a shadow of her former self and, shortly after his resignation, she was given notice. She lost her spark and fell ill. Eile looked after her through her final days in a hospital outside Kraków. Eile himself, already retired, directed photo shoots, drew a bit for “Przekrój” (and even for its competitor, Szpilki), and once more fell happily in love.

After Eile’s departure, the magazine began to lose its light, cosmopolitan character, becoming more Cracovian and conservative. The alchemy of the magazine, carefully composed from the manifold irreplaceable skills, energy and passions of a particular group of people, vanished. However, the influence the magazine had built up over many years was so great that its readers stayed loyal. Even children born in the dying years of Polish socialism remember Rozmaitości (Miscellany) from the final page and the beloved dog Fafik – allegedly modelled on Eile’s pedigree terrier – who wore shoes and did with his owner precisely what he wanted. For years, the column Myśli ludzi wielkich, średnich i psa Fafika [The thoughts of the great, the average, and Fafik the dog], which combined quotes from the classics with philosophical defiance and the sense of humour of the editors, was guaranteed to deliver a dose of sincere laughter. Memories of the typical “Przekrój” colours, warmth and intelligent humour stayed alive among several generations of Poles, in spite of the turbulent times the magazine went through after the political changes of 1989.

“Przekrój”’s night

Everything changed in the newly-democratic Poland. Foreign influences poured through the open borders. The media copied Western models. New fashions appeared, new layouts and printing techniques. Everything was different; yet again, the Poles went through a revolution in culture, aspirations and tastes. A duo like Marian Eile and Janina Ipohorska would have been priceless in this chaos, but “Przekrój” fell victim to chance; new owners and editors came and went, along with new concepts for the magazine. Publication dates and editorial teams were constantly changing. In 2000, the editorial team was moved to Warsaw. Its readership was falling, and a magazine focused on culture and society found it hard to compete on the one hand with the weekly opinion magazines, and on the other with luxury lifestyle magazines. In September 2013, the final issue of “Przekrój” was published.

“Przekrój”’s dawn

Readers had to wait three years for the new “Przekrój”; now a quarterly, but again steeped in the spirit of Eile and his editorial team. The inaugural issue was published in December 2016. Interest was so great that two additional print runs were needed. The issue had a record circulation of 150,000, and readers signed up on lists at kiosks to wait for the magazine to be delivered – exactly as had happened during the height of its popularity half a century before.

“Everyone said it wouldn’t work,” recalls Tomasz Niewiadomski with a smile. He is the publisher and photographer who bought ownership of “Przekrój” in 2013, and rediscovered it both for himself and for readers. He learnt of the opportunity to buy the magazine – along with the rights to the archive – on a Thursday, and had to take a decision by Monday. For three days and nights he immersed himself in the history of the magazine. He was both delighted and amazed by what he discovered, and decided not only to save the heritage of “Przekrój”, but also to give it new life. The new owner immediately felt the weight of expectation, receiving hundreds of emails with questions about when and in what form the magazine would return to the market.

After three years of conceptual work with the participation of the new creators of the magazine, including Marek Raczkowski (now Chief Illustrator of “Przekrój”), Marta Wardin (Publishing Director), Miłada Jędrysik (Editor-in-chief) and Joanna Domańska (Creative Director), “Przekrój” was reborn as a quarterly. The first issue in December 2016 included a comprehensive profile of Marian Eile; the graphic design referenced the original “Przekrój” style of its legendary creator. The magazine retained its classic elements, including the publication of Rozmaitości (Miscellany) on the back page, and drew on the works of its most important illustrators and photographers. To this list were added the names of new authors of texts and illustrations.

Once again, the impossible had been achieved: in an already global and heavily-digitalized world, an unhurried magazine was created; one that was apolitical, produced with humour and with a light touch, even in the most serious sections. And, once more, the editorial team and content of “Przekrój” are a microcosm of a group of people, with their skills, talents, interests and convictions, who hope still to have some influence, if not on the fate of the world, then maybe on the pleasure of living in it.

“Przekrój”’s civilization – a foundation

In December 2018, “Przekrój” began a new chapter, becoming a foundation. Its task is to publish a quarterly magazine and to look after the heritage of “Przekrój”’s civilization, as well as to translate it into the language of today, to support artistic diversity, good relations between people and nature, and to inspire the imagination. “Przekrój” wants to share knowledge, support other organizations that bring together like-minded individuals, and protect the environment. The old “Przekrój” organized jazz parties and unobtrusive social campaigns. Today’s “Przekrój” creates avant-garde electronic festivals, with the series Przekrój prosi do tańca [Przekrój invites you to dance], the LABA festival under the title ‘All is one’, and also supports the improv shows of Comedy Club performers. It remains, like its post-war incarnation, the unofficial mouthpiece of nice people.

But it is also plugged into international culture and content circulation. Just as, in the past, the cosmopolitan character of the magazine was important for Eile, today the “Przekrój” Foundation takes care of the global dimension. The subjects covered in the quarterly are current and live topics in every corner of the world, hence the ambitions and plans for the international development of the magazine. Since 2019, the English-language website of the magazine has been expanding its content and, in the near future, the global Polish version of “Przekrój” should reach readers and recipients abroad. The magazine may have retained its retro style, but has quickly established itself in the world of new technologies and new media. The entire “Przekrój” archive has been digitalized and is available online for convenient review and reading, alongside all the new issues of the magazine, which can be ordered not only in print, but also via online subscription. The mighty “Przekrój”, with all its various little pieces of civilization, fits fantastically well on a smartphone.

Check for yourselves! Fafik the dog, Professor Filutek, and Stanisław from Łódź are waiting for you, all now in multimedia form. In preparing this text, I drew on the magazine’s archive and the following books, which I warmly recommend to those who can read Polish and are keen to learn more about “Przekrój”:

Andrzej Klominek, Życie w „Przekroju”, Oficyna Wydawnicza Most, 1995;

Agata Szydłowska, Paryż domowym sposobem. O kreowaniu stylu życia w czasopismach PRL, Muza, 2010;

Tomasz Potkaj, „Przekrój” Eilego. Biografia całego tego zamieszania z uwzględnieniem psa Fafika, Mando, 2019.