Sensational. Surprising. Shocking. These are the words that have probably been used most often to comment on the verdict of the 74th edition of the Cannes Film Festival. The jury, chaired by Spike Lee, awarded the Palme d’Or to French director Julia Ducournau for her subversive feminist body horror film Titane. Thus she became only the second woman in the festival’s long history, after Jane Campion, to receive the most precious laurel on La Croisette.

The 37-year-old Julia Ducournau made her name (also at Cannes) in 2016 with her debut feature Raw – winner of the Critics’ Week FIPRESCI Award. Immediately, she was dubbed the ‘queen of gore’, and has reaffirmed her title as the chief extremist of modern cinema with her latest work. She definitely does not shy away from extremes in Titane; the bodies are piled high, and blood gushes out in all directions. Those of a more sensitive disposition left the screening room in terror, while the more resilient wriggled nervously in their seats throughout the screening.

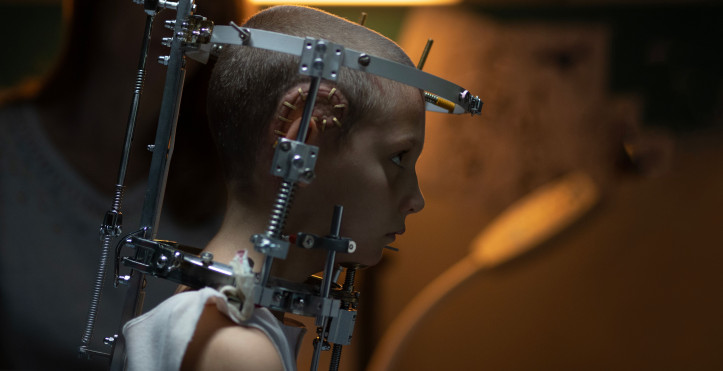

The protagonist of Ducournau’s film is a 20-year-old girl named Alexia (played by the excellent debutante Agathe Rousselle), who has to live with a titanium plate in her head due to a car accident in her youth. She works as a dancer, and after hours she is a ruthless killer who shows no mercy to anyone who stands in her way. When she feels the police breathing down her neck, she decides to change her identity and pretend to be a man: the long-lost son of a fireman (Vincent Lindon). Titane is a visual feast and one of the most original and simultaneously extreme stories about… love and the need for closeness. It is also a film after which you will never look at the “Macarena”, so popular in the 1990s, in the same way again.

Kuba Armata: when watching your film, it’s hard not to think about such genre classics as David Cronenberg’s Crash (1996) or John Carpenter’s Christine (1983).

Julia Ducournau: I think I use genre as a tool in my films, as a way of not using too much dialogue, of not explaining everything. This also has to do with my relationship to image. Talking of Cronenberg, do you really need to explain what happens to the hero in The Fly (1986)? It’s all there, it’s all clear in gore and body horror movies. I like to use genre to create a link between the audience and my character that is not intellectual – it’s more of a physical bond. There is a common knowledge about the body and what it can go through that we all have. And it makes us all equal in the room, because we know that what is happening on screen must hurt or be uncomfortable. It creates a bond that is immediate. You don’t need to relate to the person morally to understand what they’re going through. That is what interests me most in body horror.

Do you like genre movies in general?

It all started with Edgar Allan Poe for me. Not as a director back then, but a writer. I discovered my love for Gothic imagery at the time I discovered his short stories and then I went on to discover films. It’s really hard to explain why you’re interested in something, though… I think that genre movies gave me as much pleasure as cartoons when I was a kid. It doesn’t mean that they’re cartoonish; they can tackle very serious subjects and it’s really important to watch some of them at least once in your life. But there is this freedom in knowing that anything can happen, which I really like. There is also this thing in cartoons where you always have the craziest death – the Coyote falls off the cliff and becomes completely flat, but it’s OK because it’s a cartoon. It’s a bit like this in horror movies as well. I’ve never seen them as something very traumatizing. It doesn’t mean that I’m not scared of anything, but I’ve never been traumatized by them. They promise another world where death can be benign somehow. This is how I saw it when I first discovered horror movies. Perhaps I think less like that now. But I do find it reassuring in a way. I’ve always felt that horror films were saying things that were forbidden, not only by your parents, but by society. And I’ve never liked things that were left unsaid. I knew from a young age that there was something there that I could not receive anywhere else in the adult world, some kind of truth.

Do your remember your first encounter with film?

My first encounter with a film in the screening room was when I was five. It was a film called The Red Balloon (1956) by Albert Lamorisse. It’s in black and white. It takes place in Paris, it’s about a little boy with a balloon, and the kid dies in the end. It’s really the most depressing movie ever, and it’s a movie for kids – they showed it to us as a class at school. It was horrible. I hated it. After that, I think my relationship to movies and cinema in general was more through stories. I’ve always been a storyteller. My parents used to tell me stories at night – like all parents – except half of the time I would be the one telling the story. I would say: “Can I create it? Can I tell you a story?” And it was very convenient for my parents, who were tired as fuck. So, yeah, I guess I’ve always loved to tell stories. I started writing from a young age: short stories and then poems and stuff like that. It never left me.

How did you transfer from this to your directing passion?

When I went to film school, I was actually in the script writing department, because I intended to be a screenwriter, and screenwriter only. But in the first year of school, we were able to direct small short films. Just to get a hint of what it is like to direct a small crew. The first time I did that, I realized something very important: that actually directing is writing. It’s exactly the same. Then when I discovered editing, I thought Well, editing is writing! and then it was the same with all the other stages. So I knew, if I’m only doing the script, I haven’t finished my work. I wanted to do that, I wanted to go through the whole writing process.

Since you are such a visual film-maker, I was wondering if your projects start with a visual idea? Or do you have topics that you want to talk about and characters that you can tell a story with?

I never really start from topics per se, it’s usually images. In Titane, though, it started with an image I had in my head, which basically comes from a recurring dream that I’ve been having for years: that I was giving birth to car engine pieces. I always thought it was incredibly creepy, but also very interesting, and I always wanted to do something with it. But the topic of unconditional love was also a big one when making the film. It exists between Justin and Adrian, because they choose each other to be their own family, their own love and their own thing, regardless of sexuality or gender. But it’s still aside from the main story, right? The story is really Alexia and how she is emancipated while discovering her own monstrosity. I wanted to set love at the centre of this film, because I realized the reason it’s peripheral in Raw is because it’s really hard for me to talk about it. Because it’s hard, I wanted to go there, since there’s obviously something there. And so I did. I took it like a challenge. I was like OK, let’s talk about love. Then I realized I can’t talk about love, I can’t find the words. It’s impossible for me.

Why?

Love is so absolute. It’s so transcending, and it implies so many things because it has so many faces. It can exist between a couple, a mother and a child, friends. But for me, love, it’s all of these combined together, it can only be unconditional, irrelevant of gender. This is really choosing someone and being chosen in return. So I decided to talk about this. But when I was writing Titane, I realized that putting words in the screenplay was just demeaning to the topic and to this absolute inclusion that love is. That’s why, in the end, you have a film with very little dialogue. As a film-maker and as a writer, I tend to really trust image. And I believe in cinema – light and scenes and all that. So I tried to go as far as I could with the image before I added dialogues over it. Here, for this particular topic, images are really just what you need. For example, in the dance scene, the pink one with all the fires. I call it the pink scene [laughs]. The moment when they start dancing together, you come to a point in the film where you don’t need any more words. You understand that now they have come to accept each other fully and that the lie they’ve been living in has become a truth.

In Titane, alongside the debuting Agathe Rousselle we also see Vincent Lindon, one of the best French actors. Apparently you wrote this role especially for him.

We’ve actually known each other for years. There is something about Vincent that moves me very much. He appeals to something in me that I can relate to. All those extremes that are just reunited in him at all times, constantly – there is no grey or beige area with that person. He’s super intense, and at the same time, very childlike. He can be also very scary – everything at the same time. I see him like that probably because I see him through my eyes, and I can relate to that because I feel that in myself as well. I wanted to film him like he was never shown before, I wanted everyone to see him how I see him. When I was writing, it was not a very conscious thing from the scratch. I realized more and more as I was writing the character that I was actually inspired by the way that I saw him and the way he moves me.

Claire Denis – another French director in whose film I saw Vincent – also seems to understand his beauty, his brutality and tenderness. Do you see a connection between how you look at him and how she does?

It’s hard to say, because I haven’t seen the movie. Please don’t tell him [laughs]. Although I’m not surprised, knowing Claire Denis’s sensitivity, that she saw that sweetness in him. As an actor, Vincent is very physical, very much in touch with his body. That’s super interesting, because I don’t like to talk about the psychology of my characters on set. I would consider this work that’s done beforehand, when we’re doing readings etc. On set, I’m really all about choreography and music. So I direct the bodies of my actors, the tone of their voices and the way the words come out, the intensity. Vincent is very much like that on set as well. So we met perfectly on this level. He hates everything that has anything to do with psychology or the themes of the film. And that’s really good, because it’s almost like mind-reading at some point. I understand why she saw that in him, because it’s really obvious: the way he moves is different in every movie he’s done.

Could you tell us a little more about the way you work with choreography? I’m thinking especially about the dancing scenes in Titane.

It really depends on the scene, honestly, because they were not all fitted the same way.

For example, the one in the car show was obviously choreographed. I hired a professional pole dancer to create the choreography with me and Agathe, because, well, it’s the character’s job, so it had to look professional. At the same time, this is a very important moment in the sequence shot: we start the sequence shot with a very, very obvious male gaze set on the girls and the cars. When you get to her, it’s like the character just transcends the male gaze, gets out of it. It’s all about her desire. And now she looks at you instead of you looking at her, because she is looking through the camera; she reclaims her body. That required very precise choreography work to convey that idea that she takes ownership of her body and of her desire on the car, whereas we started with a male gaze that makes the women passive in the shot.

Was your approach different in the other dance scenes?

Yes. For example, the scene where all the firemen dance together – actually, half of the actors were real firemen and half of them were dancers. I wanted to add some dancers in there because I did not want it to be too stiff; I wanted to have something that was poetic, that would go well with the slow-mo. By the way, this shot was actually way longer originally, because of my passion for sequence shots [laughs]. But we cut it, obviously, and in the narration, this scene is something that is spontaneous. It’s supposed to look normal: some people dancing because they’ve just gathered round and it’s the end of the day, and they need to blow off some steam. It’s not a musical, you see. The characters are not talking and then suddenly starting to dance. I always use dancing scenes coherently with the rest of the narration.

What does that mean exactly?

Through dancing, you actually understand the evolution and the stakes of the character without a word. It’s really visible in the scene with the firemen and stuntmen – one of my favourite scenes of the film. At the beginning, you start with something that is stereotypically masculine, full of testosterone: all these big, bulky bodies just jumping on each other and showing who’s the strongest. Then, when Alexia gets up on the fire truck, all of a sudden she’s trying so hard to belong, to be a man… She’s alone there and all she can do with her body is what she knows, what her body knows. But she’s not the same person that she was at the beginning of the film – it’s still her, but different, she’s her own person. I don’t know if you noticed, but some of the guys that are dancing around her actually look like her. I wanted the viewer to lose track of who is who at some point. She becomes her own person, and at that moment her gender is just irrelevant. I really love this scene for that.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.