“The romantic template of love is a historical creation, a hugely beautiful and often enjoyable one. But we can state boldly: Romanticism has been a disaster for relationships!” Author and philosopher Alain de Botton decodes love.

Aleksandra Reszelska: People are enchanted by the idea of love. Writers, musicians, psychologists, even mathematicians – all of them make their attempts to grasp love’s essence. In 1993 you wrote a little book On Love. And then, over 20 years later, you decided to create a sequel, The Course of Love. Why again?

Alain de Botton: Well, the quality of our relationships is simply the most important single determinant of our happiness. Money, power, status, work – these are important, too. But love is the key. I have always been fascinated by how tricky love remains to get right. No-one around me has the solution. Still, I was tempted to say what I believe love is and how it can go better.

And so you write: “Love is a skill, not just an enthusiasm.”

Yes, and I feel that this notion is the secret of a happy relationship. Love is not just a feeling. And it is a rather glorious and honourable thing to put one’s own needs aside to work for the happiness of another human. We are so used to the idea that being loved is the natural state. Often it is a beautiful surprise to imagine that love could also be about selfless service.

I have always loved this one definition of love by the American psychiatrist and spiritual writer, M. Scott Peck: “Love is the will to extend one’s self to nurture one’s own or another’s spiritual growth.” It rings true with what you are saying.

Yes, and we see this most obviously in the love that parents have for their children. They genuinely and selflessly care for them. This is very hopeful. We need to love our lovers with some of the attention and imagination we naturally use for our children.

What does love mean to you?

Love is a sense of being in deep sympathy over fundamental issues, which can be no grander than how to cook a dish or what role a grandmother should play in one’s life. My point is: these pragmatic things matter to you, and it is lovely if they matter to your partner as well. Love involves a feeling of being completed by another person. Your flaws are being corrected by the presence of another. Perhaps they bring you confidence or allow you to be in touch with shyness. Maybe they are scientific or delightfully artistic, strong or weak. Whatever it is, our delight comes from a feeling that our characters are being rounded out and finished by our lover.

We know when infatuation starts – it is all butterflies, dizziness and daydreaming. Mature love is said to begin after the first crisis. But when does love end?

Love ends when we cease to forgive or when we can no longer imagine that the partner is ‘good’. In a sense, everyone always has some goodness in them. So – to an extent – the failure of love is a failure of our moral imagination.

You often claim that no-one did as much harm to the human perception of love as the Romantics.

Since around 1750, we have been living in a highly distinctive era in the history of love. Romanticism emerged as an ideology in the minds of European poets, artists and philosophers, and it later conquered the world. The romantic template of love is a historical creation, a hugely beautiful and often enjoyable one. But we can state boldly: Romanticism has been a disaster for relationships! It is an intellectual and spiritual movement, which has had a devastating impact on the ability of ordinary people to lead successful emotional lives. The salvation of love lies in overcoming a succession of errors within Romanticism.

What does this romantic template of love look like?

No single relationship ever strictly follows the romantic template, but its broad outlines are frequently present nevertheless. They follow a set of rules.

First, Romanticism is deeply hopeful about marriage. It took marriage and fused it with the passionate love story to create a unique, if impossible, proposition: the life-long passionate love marriage.

Then, along the way, Romanticism united love and sex. Previously, people had imagined that they could have sex with characters they didn’t love and that they could love someone without having unforgettable sex with them. Romanticism elevated sex to the supreme expression of love. Frequent, mutually-satisfying sex became the bellwether of the health of any relationship. Without necessarily meaning to, Romanticism made infrequent sex and adultery into catastrophes, putting a lot of pressure on married couples. They started to believe that one should raise a family without any loss of sexual or emotional intensity.

Also, sadly, Romanticism proposed that true love must mean an end to all loneliness. The right partner would, it promised, understand us entirely, possibly without needing to speak to us. He or she must be our soul mate, best friend, co-parent, co-chauffeur, accountant, household manager and spiritual guide. They would intuit our souls, which altogether is, as you know…

…a complete fallacy.

Exactly. But the list of mistakes and errors of Romanticism continues. For example, it has manifested a powerful disdain for practicalities and money. It feels cold – or just unromantic – to say you know you’re with the right person because the two of you make an excellent financial fit or because you gel over things like bathroom etiquette and attitudes to punctuality.

And the biggest romantic mistake?

The belief that true love is synonymous with accepting everything about someone. The idea that one’s partner (or oneself) may need to change is considered a sign that the relationship is on the rocks. “You’re going to have to change” seems like a last-ditch threat.

These myths have perpetrated our belief system for years through art and culture. Is there any particular one that you dislike the most?

I guess I hate the claims that we don’t need education in love. We may need to train to become a pilot or brain surgeon, but not a lover. As if we could pick that up along the way.

Your friend, John Armstrong, says that one of the main principles of the School of Life is working to disprove this romantic notion that we can’t learn love.

We need to piece together a post-romantic theory of couples, which would replace the romantic template with a psychologically mature vision of love. Let’s call it classical. It would encourage in us a range of unfamiliar but hopefully effective attitudes.

Such as?

Believing that it is normal that love and sex may not always belong together and that discussing money early on in the relationship is not a betrayal of love. Also, knowing that we are flawed, and our partner is too, may greatly benefit a couple. It simply increases the amount of tolerance and generosity in circulation.

In the past, it took a village to build a healthy family and raise children, and also to become the person we want to be.

That is why we should also understand that we will never find everything in one other person, nor they in us, not because of some unique flaws, but because of the way human nature works. We need other people too! And we have to know that spending two hours discussing whether bathroom towels should be hung up or left on the floor is neither trivial nor unserious; there is a special dignity around laundry and timekeeping. All these attitudes and more belong to a new, more hopeful, post-romantic future for love.

In her brilliant TED lecture on desire in long-term relationships, Esther Perel claims that what we search for in our partners are impossible and contradictory feelings: novelty and familiarity, excitement and security. Is this the reason why almost half of all marriages fall apart?

Yes, the problem is that modern marriage is a fusion of two things: the marriage of reason (based around raising children and managing family money) and the passionate love affair (based around terrific sex and a union of souls). But unfortunately, we have insisted on conjoining two ingredients that seldom exist together. So, we have to be very, very lucky if we find them and make them stick.

What are the ingredients of true love for Alain de Botton?

Love is an admiration for the strengths of another person. Especially those one doesn’t possess oneself, combined with a capacity for compassion for weaknesses and flaws.

Can we love better?

Yes, we can make improvements, chiefly by recognizing that we are very disturbed people and therefore need to explain our neuroses to our partners in good time and be very gentle towards their own disturbances and quirks. It’s all about the communication of complex material.

Do you think that love can last forever, or maybe it ultimately has to be impermanent?

It is a bit like asking: can someone write a novel as great as Anna Karenina, a piece of music as splendid as “Mass in B Minor”, or create an invention as impressive as the Eiffel Tower or penicillin. The answer is, of course. But it’s hard, oh so hard, and very unlikely…

This interview was carried out in May 2016. Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

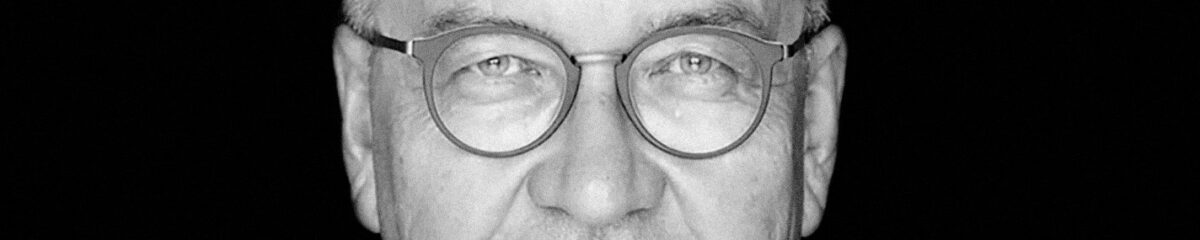

Alain de Botton:

An internationally-renowned philosopher and bestselling author. He writes and lectures on philosophy’s relevance to everyday life. His book Essays in Love sold two million copies. He is also a co-founder of The School of Life, a global education platform dedicated to fostering emotional well-being.