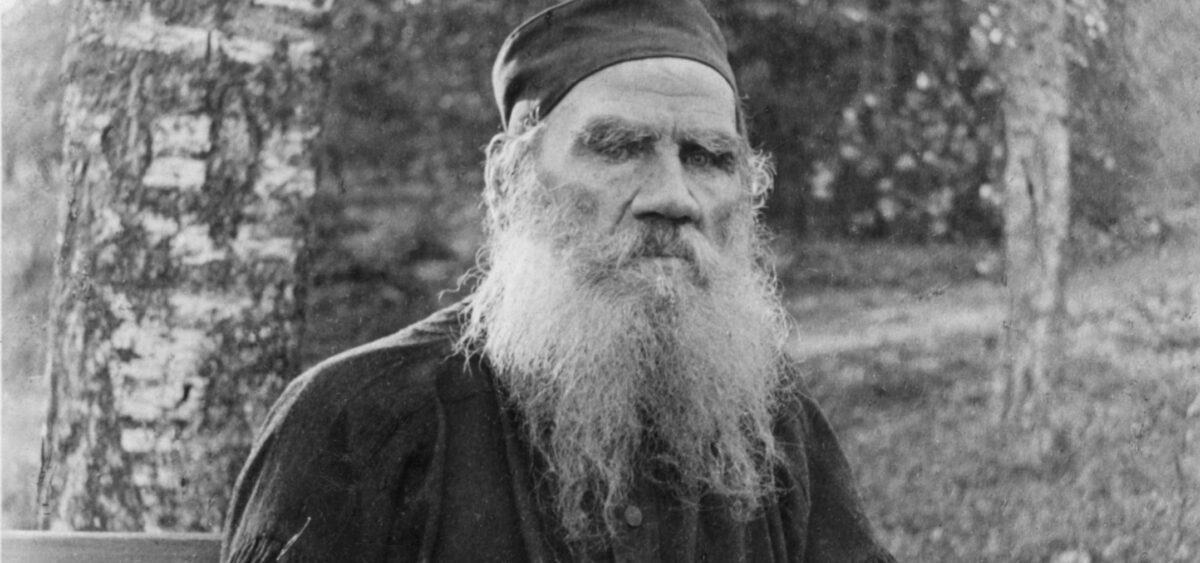

Leo and Sophia both loved and tormented each other. How did the brilliant writer live out his last months in the dense net of mutual expectations and demands?

When he died, the people dispersed quickly. In the room, there was no-one left except for the train station manager and the great writer’s physician, Dušan Makovický. He was the one to close Tolstoy’s eyelids and tie a scarf under his chin. To the railwayman, he said: “Neither love, nor friendship, nor devotion could help him.”

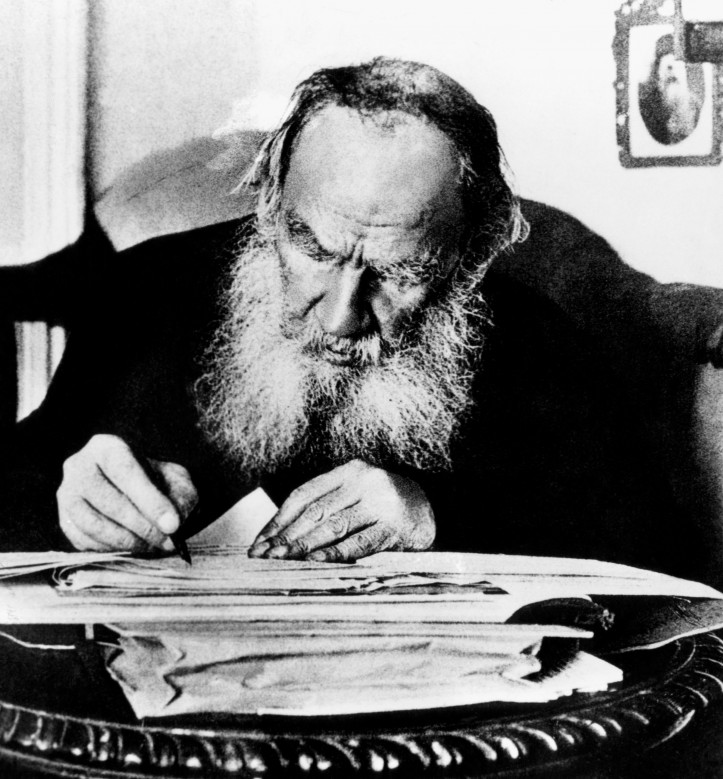

What Makovický meant were not the reasons for Tolstoy’s death, but rather the sheer scope of life’s misery that the most famous writer of his time was trying to escape, to no avail. Leo Tolstoy passed away in the early morning hours of 7th November 1910, in the railwayman’s modest home by the small train station Astapovo, later renamed Leo Tolstoy. His death was a spectacle, a great scoop for the crowds of journalists, and a premonition of the madness that fame turned out to be for so many celebrities of the 20th and 21st century. Tolstoy’s passing was also the final defeat for his loved ones, whom he both loved and fought, admired yet misunderstood. To him, death must have been the long-awaited relief of which he wrote in his journals, increasingly desperate and trapped in his own life. For years, he was growing weaker, often falling ill or fainting. Regardless of it all, he sensed he was about to lose his last chance to look for his paradise on Earth – and so he decided to give it a try. Tolstoy was 82 by then, and his run for freedom took just three days. Then, they caught up with him.

The notebook in a shoe

Lev Nikolayevich was frightened of his wife. Sophia had long taken all power over the house, the family, a large portion of the family’s wealth, and over her husband. She watched over him with obsessive devotion, deeply convinced of her saintly dedication. At night, Tolstoy could hear the floorboards creak as she slinked outside his bedroom, entering to read his notes, look for hidden notebooks or find any last wills. It happened for years. On the night of 27th October 1910, Tolstoy finally decided to flee; after years of dreaming about freedom, pushed to the limit by the torment of the last few weeks. Several days later, he wrote about his effort: “I looked up and through the crack I see bright light in the study and rustling. It is Sophia Andreevna searching for something, probably reading. The day before she asked me not to lock the door. Both of her doors are open, so she can hear the slightest movement on my part. Day and night my every word and action have to be made known to her and are under her control […] The disgust and indignation grow; I gasp for breath, take my pulse: 97. I can’t lie down and suddenly make the final decision to leave.”

In the conflicted family, Tolstoy’s daughter Alexandra took her father’s side. Now she helped him pack, quietly and hastily, together with the author’s physician, Dušan Makovický. While they busied themselves collecting his things, Tolstoy went to the stable and told the stableboy to hitch up the horses. It was so dark outside that he got lost, fell into the bushes, hit something and fell. The writer was in a dither, not believing he could leave without a hysterical row, one of those he’d grown to expect from Sophia over the past few decades. When it came to histrionics, Sophia knew how to do it. There would be screaming, wailing, dramatic gestures, gun-shooting, numerous suicidal attempts – all of it served regularly in the Tolstoy family estate Yasnaya Polyana, in which he grew up and spent most of his life.

Sophia had numerous reasons for despair, not all of them being due to emotional spectacle or blackmail. She also suffered, which made Tolstoy even more afraid and eager to surrender. He, the famous novelist famous both at home and all over the world, called Russia’s second Tsar by some, author of such works as Anna Karenina and War and Peace, read by millions of people in various languages. A philosopher and intellectual wishing to save the soul of his nation, almost a lay saint who attracted endless pilgrimages of guests, admirers, publishers, inquirers and powerful figures, he never found any strength nor sense of power in those gestures; he never wanted them and avoided them at all cost, hiding and cowering at his own home, silent, yielding to the pressure. He would do anything to avoid conflict. The hours spent horse riding were the only moments of peace and solitude. He rode over 20 kilometres daily, almost up to the end of his life. Tolstoy would ride the woods, fields and meadows around Yasnaya Polyana, knowing that the moment he was back home, he wouldn’t get a moment of peace. Once, he obtained a small notebook in which he could write down his deepest thoughts; he would keep it in the leg of his boot, afraid that one of his children or Sophia would steal it and read his notes.

He was right to worry: one day, as he fainted and fell on the floor, the notebook slid out of his boot and was, of course, confiscated. All the fights between Leo and Sophia stemmed from their drastically different life philosophies, contrasting needs and visions of how they should spend time together. On top of that, the couple’s arguments about money issues kept growing harsher as years went by, slowly transforming into a nightmare of a toxic relationship, intimate and insufferable at the same time.

The opening sentence of Anna Karenina is one of the best-known in the history of literature. In Constance Garnett’s translation, it goes: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Indeed, many biographers racked their brains over the convoluted, tangled relationships and events that took place in Yasnaya Polyana, making for a dense net, spun by many people at once.

Leo and Sophia loved and tormented each other. He wished for a simple life near nature, devoid of all luxuries – and radically so. The writer enjoyed sleeping on haystacks, working in the field, conversing with peasants. The aristocratic and bourgeoisie families of Tolstoy and Sophia had nothing he could possibly want to include in his life. Leaving the world of excess, power and conventions was a dream he followed, often to remote parts of eastern Russia.

She wanted the very opposite: to live under the conventions of her social class and the ideas that were instilled in her when she was growing up. In the early stage of their marriage – which lasted 48 years – Tolstoy delegated the management of all household affairs to his wife. She was to count every kopeck, watch over the servants and take care of the family’s needs. They had 13 children together, seven of which survived – followed by 23 grandchildren. There, among it all, just one man of extraordinary talent for which Russian publishers were ready to pay with gold. The more he was adored, the more repulsed he became, the more desperately he tried to detach himself from the public persona forced upon him by millions of admirers. He turned his back on ownership, wealth, and all tokens of the elite lifestyle. This man – whom Russians considered an oracle and who to this day remains a symbol of genius writing that encompasses the essence of Russia’s life and spirit – had spent most of his life striving to break out of the mould of his identity and social context. Tolstoy gradually abandoned all the limitations of his social class, its customs, titles, preassigned social roles and the obligations they entailed. However, while he kept trying to break free and reach the pure ideal, he failed time and again. He could feel his free spirit falter and fade. When he decided to run away, Tolstoy knew it was his final chance to protect the last genuine, unsuppressed part of himself.

Tolstoy and Makovický reached the train station. The writer had just nine roubles on him. Just before the carriage left the estate, Alexandra pushed 300 more into Makovický’s pocket. At the train station in Shchokino, Tolstoy and his physician bought two tickets to Gorbachevo and then waited three hours for the train. All that time, the writer was frightened that the chase was already after them, expecting his wife to appear at any minute. Later, he wrote: “But then we were in the carriage, the train started, and my fear passed, and pity for her rose up within me, but not doubt about having done what I had to do. Perhaps I’m mistaken in justifying myself, but I think it was not myself, not Lev Nikolayevich, that I was saving, but something that is sometimes, and if only to a very small extent, within me.”

There was no plan. The writer did not know where he wanted to go. Neither did he think of losing the chase – say, by buying a ticket to somewhere farther and getting off a few stations earlier. But could a man as famous and celebrated in Russia as Tolstoy ever hope to hide at all? Even before they reached Shchokino, as they made a short stop to fix the reins, people poured out of their huts in the village, having recognized the author instantly. On the trains, it was no different: passengers surrounded him immediately, hats in their hands; some just looked at him, embarrassed, while others went on to discussing various world matters straight away. He was admired, but also well-known for his love of the people – which was why so many people felt allowed to approach him or ask a few questions. Many had no reservations about sending him letters pleading for financial help, support for their business, and all kinds of assistance. There wasn’t a day without dozens of letters arriving at Yasnaya Polyana, from the rich and influential, as well as from barely literate peasants. The whole world wanted something from him.

Leave it to the birds to fly

There were many speculations about the reasons for Tolstoy’s escape, and the real point and purpose of his last journey. Some say he went looking for death, but the course of events does not confirm anything of the sort. And anyway, Tolstoy described all of his life in his journals, explaining his motivations and meaning for things great and small alike. None of his writings or comments suggested that Tolstoy had suicidal intentions when boarding the train. The opposite seemed to be true: he was hoping to spend the last moments of his life the way he had always wanted: in solitude, without comforts nor fuss.

In Gorbachevo, where Tolstoy and his physician consulted railwaymen about possible routes, the writer approached some boy, with whom he walked for a while on the platform. Suddenly, Tolstoy decided that Makovický and he would board the same train the boy took to school and go to a small town called Kozielsk. The writer insisted they travel in one of the cheapest carriages. Old, weakened Count Tolstoy sat on a hard bench, wearing a quilted russet and sermyaga (a peasant coat), boots with tall legs, and a yarmulke on his head. After a while, he was struggling to breathe. The carriage was stuffy; the air heavy with smoke from rolled cigarettes. Tolstoy retrieved a fur coat from his luggage, put it on together with a fur hat and warmer shoes, and went to stand on the rear platform outside the carriage. However, it was crowded there, too, and people were smoking as well. So he went to the front of the train and stood on a platform near the locomotive. It was not as packed there, but very windy. Tolstoy stood there for about 45 minutes, ignoring Makovický, who asked him to go inside, worried about the writer catching a cold. Back in the carriage, Tolstoy continued his conversations with other passengers. One young schoolgirl told him with great delight about how far human civilization had come, proclaiming that man was already capable of flight. Makovický remembered the writer’s response well: “Leave it to the birds to fly.”

This one sentence opens up the whole universe of Leo Tolstoy’s opinions and his deep apprehension towards the so-called achievements of civilization. He considered them manifestations of evil, gained for the price of one’s soul. He hated large cities, believing them to be centres of depravity. Tolstoy’s stance on the matter could be explained by his past experiences. As a young aristocrat, the count led a dissipated life in Moscow, full of gambling, paid sex, alcohol and debt, all the way down to absolute oblivion. He couldn’t break free and stop. Lust, he noted, tormented him all the time (although later, his biographers would tone it down). Most likely, the intensity of Tolstoy’s sexual urges did not exceed that of a regular young man – still, he never stopped feeling guilty about them. Since he felt it to be a work of Satan, he desperately sought for a way to become comme il faut, proper and of acceptable character. Such a turn seemed to echo the conventional educational methods applied by Tolstoy’s aunts, who replaced the mother and father that the young count lost in his early childhood. Before turning nine, Lev Nikolayevich was already an orphan.

Another way of escaping the darkness of his nature was to leave Moscow and travel to Crimea to fight in the war. Tolstoy was hoping that the simplicity and discipline of military life would provide him with a solid framework to protect him from his weaknesses. Fascinated with the Cossacks who lived in the grassland and were always on the road, Tolstoy saw them as perfectly free and close to nature. He loved Crimea’s vast swaths of land, simple villages, life far away from the big cities. Meanwhile, he tried to have a career in administration and in the army, but to no avail, turning out to be a mediocre clerk and an unexceptional officer of no merit to speak of. At the same time, his early stabs at prose were appreciated straight away. People wanted to publish his works immediately, offering him money from the very beginning. And yet Tolstoy – whose talent turned out to be as extraordinary as it was unquestionable – could not find any fulfilment or solace in his greatest talent, which moved so many people so deeply, and who considered his writing to be the most sincere reflection of Russia. Ceaselessly and endlessly, Tolstoy chased not his satisfaction but some connection to a power greater than himself, greater than the people around him whose banality and vanity he could not ignore.

Still, Tolstoy was far from condemning anyone. He was tangled and tormented in a hopeless trap of all those things he considered trivial and meaningless – yet literary experts refer to him as a writer who loved people deeply, always able to see their passions and idealistic dreams, as well as their weaknesses. The world of his novels was just as complex, paradoxical, rich in impossible ambitions and ethical dilemmas as life was for people living in the 19th century.

However, the very reality he immortalized in his writing was the one he strived to escape: how ironic. Of course, to consider Tolstoy merely a documentalist of his times would be an understatement; when reading his works today, those more and less famous alike, we can see our reflection within them just as clearly. Tolstoy viewed himself and man in general in all his complexity with compassion and great hope for improvement, unfalteringly convinced that paradise is possible and within reach. But whenever he tried to find it or build his own, he failed.

To teach and to feed

Tolstoy was planning to marry the much younger Sophia Berg. He was infatuated with her, although to the very last moment, it seemed unclear whether he would propose to Sophia or her older sister. Therefore, Tolstoy chose to marry out of his own free will. The count wanted to start a family and expected to turn his inherited estate in Yasnaya Polyana into his perfect bubble, a paradise on Earth. It was not his first attempt to negotiate with the world, but the approach he chose was somewhat unusual. Just before tying the knot with Sophia, he showed her his journals. Having read them, the girl was shocked. Sophia, the young daughter of a well-off Moscow doctor, had wept at the very thought of leaving her family behind, but was set to serve as the lady of the house in Yasnaya Polyana to the best of her abilities, and take care of Count Tolstoy with all her might. Sophia also kept a diary: there, she wrote about the shock of finding out what kind of man she was about to marry. After she arrived at the estate, someone promptly showed her one of the local peasant girls, described at length in her diary; as it turned out, Tolstoy was deeply in love with her. The beginning of Leo and Sophia’s union was a rocky one. Over time, the tension only grew.

Tolstoy was not fit for running Yasnaya Polyana. He did try, but it soon turned out that looking after the fields and orchards was not his forte, neither was crop trading. It became clear that all those duties would fall on Sophia’s shoulders. She tried to please her husband, giving birth to one child after another. The cost of living went up, while their income remained modest: Yasnaya Polyana was never very profitable (Tolstoy’s biographers examined his finances in detail). Meanwhile, the writer was busy with his search for redemption – for himself, the people, and all of Russia. He wore peasant russets, spending hours and days walking on the track (later replaced with a road) frequented by pilgrims, preachers, shamans of all sorts, as well as the poor from the village. Tolstoy was eager to talk to them, envious of the simplicity of their lives. He did, however, know the bottomless Russian poverty all too well, and so he tried to help out. Whenever he had some money on him, he would give it away, along with food or furniture. Because of Tolstoy’s worldview, all meals served in Yasnaya Polyana were vegetarian and light on the liver.

Sophia was wringing her hands trying to patch up the holes in the home budget, torn by her husband’s generosity, just like she kept on patching and trimming everyone’s clothes. She was diligent and willing to work a lot, but she had her boundaries, too. Whenever Tolstoy threw himself into farming, pulling Sophia and their children with him, she agreed to reap wheat or trim orchard trees – but she would never turn manure. Meanwhile, Tolstoy was committed fully, with all his might. He wanted to shed all his reservations and free himself from everything that distanced him from the simplest and poorest of people. He set up a village school in which he taught children along with hired teachers. There was no strict curriculum, no lesson plans, no homework – children were educated more informally. In 1891, when a great famine hit Russia, Tolstoy established several eateries. Such independence was not welcomed by the tsarist authorities, even if just because it was not pre-approved. Tolstoy acted on his own accord, organizing mutual aid that the authorities would soon shoot down. Neither the school nor the eateries stayed for long. While the writer was protected by his status, the vision of having him arrested did come up in official documents and was more than an empty threat. And so Tolstoy gave up on his charitable efforts, deeming them not good enough, unable to deeply transform the nation and the country in which he lived.

It wasn’t that he was afraid. People did say that Russia had two tsars, but they were also quick to add that, while Nicholas II had no power to destroy Tolstoy’s authority, the writer did undermine him with his books and actions. Leo Tolstoy was not politically engaged, but Russia buzzed with the need for change. The country was brimming with the oppressed, the poor, the terrorized – thus revolutionary moods fermented. On such a backdrop, Tolstoy’s radical views (such as property being the work of evil, meaning that nothing should ever be privately owned) had to be seen as an attack on the still-absolute power of Tsar Nicholas.

The writer himself was firmly against every form of violence. For years, he developed his philosophy on not opposing evil, but searching for and building enclaves of goodness instead. Tolstoy’s thought inspired Mahatma Gandhi, the future leader of India’s great independence movement. By the late 19th century, when Gandhi was still active in South Africa, he set up a farm there that he named Tolstoy.

The writer’s peaceful philosophy was, however, met with increasingly brutal reality. In the early 20th century, Russia fought and lost a war with Japan, its failure exposing the weakness of the tsar. The atmosphere in Russia was heavy with the need for change, and new groups opposing Nicholas II were forming while the repressions and fear grew, as did the tension. Meanwhile, Tolstoy did not engage with current events, being absorbed with more universal issues.

At the same time, he was increasingly overwhelmed with the prose of his own life, as he had no power over the ways it was changing. After War and Peace was published in the late 1860s, the book soon became a national epic. In the 1870s, when Anna Karenina – centred around questions of guilt and betrayal – came out, the writer’s position was cemented. Anna Karenina soon became an international example of writing about love against social conventions, and Tolstoy’s worth skyrocketed. Publishers were ready to pay millions of roubles in gold for the rights to publishing his books. But the more celebrated and appreciated Tolstoy was in the world, the less he enjoyed writing. His wife pressured him to write popular and profitable books to earn them a living and help support the Tolstoy estate. She also made efforts to support her husband in his writing, and as readers, we owe a lot to Sophia, who rewrote Tolstoy’s most famous works time and again by hand, adding changes and corrections. She negotiated with publishers to release the books in which Tolstoy wrote about things not welcomed by the authorities. Finally, she pressured her husband into giving her the rights to all his writings created before 1881. It was Sophia who managed Tolstoy’s most prestigious books and the income they generated, quickly consumed by the large family and estate.

Time to run

Tolstoy’s popularity and his potentially enormous wealth turned out, as one of his biographers put it, to have an explosive impact on the peace of his home. Tolstoy’s loved ones might have admired him for his charitable nature and eagerness to give his last shirt to a peasant – but they failed to understand why he readily rejected the millions of roubles that could have changed their lives, too. Tolstoy’s relationship with his sons was strained: he thought them reprobates, irresponsible with money and their own lives alike, and they felt bitter about their father not leaving them the fortune they might have hoped for. Both sides of the conflict were growing increasingly radical. Finally, Tolstoy publically relinquished the rights to all his works and made several attempts to compose his last will, in which he wanted his inheritance to be given to the public instead of passed on to his family. The writer wanted the people to have access to something he viewed as vital for their souls. Sophia suspected him of such efforts and did everything she could to sabotage him. In the Tolstoy household, there were no secrets – there could not be any, since both Leo and Sophia wrote extensive diaries, offering each other near-absolute transparency.

The diaries became the third force in their marriage, almost equally important as the two of them, the first emerging right before the couple tied their knot. That’s when Leo forced young Sophia to read the notes from his youth, and for some reason, she picked up on his game. Since the very beginning of their marriage, both parties wrote diaries and read one another’s notes. Whatever was not expressed in conversation was sure to find its way onto the page. They did not write to look for privacy, but communication. They could feel the spouse always looking over their shoulder, and so they could never be fully honest. At the same time, they communicated this way for years, until the very end, robbing each other of their intimacy and weaving a dense, unbreakable bond. They knew all about each other – and because of it, when Tolstoy was planning his escape, he was almost certain his run for freedom would be in vain.

When the count and his physician reached Kozielsk, Tolstoy knew where he wanted to go next. He rented a horse carriage to take them to a hermitage in Opta, located only several kilometres away from Sharmardino, where his sister Mariya lived. Tolstoy had visited both Opta and Sharmardino before: it was an obvious place to look for him. While the writer travelled, Sophia was out of her mind with worry. And literally so: within several hours, she made two suicide attempts, but was stopped both times. Once it became clear which way Leo had gone, she sent some people after him and readied herself for the road, too. She also sent out letters, terrified by losing her husband just as much as she was of the international shame his escapade would bring upon her. After all, she was married to one of the most famous men in the world.

Once Tolstoy reached the Optina Monastery, he felt joy. “What a wonderful place!” he said to the innkeeper. Sitting in a modest room, he wrote a letter to his daughter Alexandra and soon went to sleep, feeling very tired. On the next day, he visited his sister in Sharmardino. He travelled by horse cart; the autumnal weather was cold, wet and windy, complete with an icy rain. Only two days had passed since his escape from Yasnaya Polyana, and yet the chase was already on. News of Leo Tolstoy’s disappearance had electrified the press, first locally and soon abroad. Special trains followed the author, carrying special correspondents from various newspapers. Telegraphs worked day and night, sending news of Tolstoy’s every move. Meanwhile, the count decided to go to the village of Rostova, where he would rent a modest cabin from some peasants and live there with them. At the train station, he read the papers, bitterly following the articles that reported on the nationwide search for him. On the way to the village, he started to shiver and became feverish. However, none of the stations they passed had a hotel to take good care of the ailing writer. Finally, Makovický decided that any further travel would kill Tolstoy.

They alighted at Astapovo, where the physician soon convinced the station manager to take the writer home. Tolstoy’s health was deteriorating rapidly, his fever crawling up to 40°C. He was delirious, moaning, tossing and turning. Meanwhile, not only journalists were approaching Astapovo, but also doctors and representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church, which years ago had officially excommunicated Tolstoy for his anti-religious publications. Now, church officials were hoping that in the moment of death, the great writer would return to faith. Tolstoy, however, while weak and feverish, remained lucid and refused to see the priests and his wife – who was also brought to Astapovo straight away. She did, however, manage to pass him his favourite embroidered pillow. There is a photograph showing Sophia, wearing modest travel garb, standing with her face near the window of the railwayman’s house, trying to look inside and see her husband. All in vain, although among his last moments of lucidity, Tolstoy did say some things that proved he cared for her. “All on Sonya’s shoulders,” he worried.

Diagnosed with pneumonia, Tolstoy was growing weaker by the minute. Unfortunately, there was no cure to such severe illness, especially for someone of Tolstoy’s age. Doctors administered oxygen, but the end was unavoidable. The tension in Astapovo kept growing, as did the crowds. At some point, the Gendarmerie was sent over in case there were riots. Inside the modest little house, the still-conscious writer was whispering: “I’ll go anywhere, just to be left alone. Let me be. I must run… I must run, run anywhere I can…” Tolstoy did not want morphine; he was terrified of any drugs and their power. Perhaps this was why Anna Karenina threw herself under the train having first numbed herself with opium? The writer sought no such relief. Yet his will was disregarded once again, and he received injections of morphine and camphor. Only when he was about to die did they let Sophia Tolstaya enter his room. She sat by his bed, stroking Leo’s forehead. He stopped breathing at five minutes past six in the morning.

The number of pilgrims coming over to pay respects to the great author grew considerably. The correspondent of Birzhevyye Vedomosti wrote: “At the station, the chaos is that of the Tower of Babel. No hope of getting through to the telegraph, everywhere is jam-packed with youth, blue student hats as far as the eye can see. Five thousand students came over from Moscow […] It is getting dark, and yet the line of people waiting to pay respects is only getting longer, to no end in sight. New mourners keep coming, train after train.”

In Moscow, paperboys handed out the latest newspaper, saying just two words: “He died.” Everyone knew who they meant. Tolstoy’s body was put in a plain oak coffin with no cross on the lid. After several days of mourning, the writer went back to Yasnaya Polyana, his only and so very imperfect paradise on Earth. There, he was buried in the woods. His coffin travelled in a regular carriage, marked ‘Luggage’.

The main sources used for this article were: Lew Tołstoj. Biografia by Wiktor Szkłowski, Lew Tołstoj. Ucieczka z raju by Pawieł Basiński, and The Diaries of Sophia Tolstaya.

Translated from the Polish by Aga Zano