Teofil Ociepka found himself living and painting under the protective wings of the Polish United Workers’ Party, but in fact his art was created under the auspices of more immaterial realms.

He was born in 1892 in Janów, near Katowice [at the time, part of the German Empire, with a high proportion of ethnic Poles – ed. note]. Teofil’s father was a miner in the ‘Kaiser’ coal-mine in Giesche (renamed ‘Wieczorek’ in 1946 to commemorate a workers’ movement activist and Silesian uprising fighter). Teofil’s mother worked as a housekeeper for the Mayor of nearby Szopienice. Little Teofil, like his peers, went to a primary Volksschule, intended for autochthonous residents of Upper Silesia. When the boy turned 14, his father died in an accident underground, and Teofil had to go to work to help his mother in supporting the family. Because he was too slender to work in the mine, he tried his hand at being a municipal messenger, then he worked in an inn, at a post office, a railway, and finally as a clerk.

In 1914, he was conscripted into the Imperial German Army, with whom he fought, among other places, in the Balkans – a region that found its way into his art later on. It was during World War I that he stumbled upon the book Oedipus Aegyptiacus. Reading this occult treatise “combined in his imagination with the world of legends and fairy tales he knew from home,” according to Seweryn A. Wisłocki (an expert in Ociepka’s art). After the war and military demobilization, Ociepka was employed as a turbine operator in the Giesche mine, where he worked until his retirement. This was when he got seriously interested in Theosophy.

He contacted the Swiss Rosicrucian Philip Hohmann of Wittenberg, who remained Ociepka’s spiritual master for the following 40 years. He sent him occultist books, but also, in time, started giving him particular tasks to fulfil. The first one was to set up an occultist centre at home; another was to spread occultism across the whole country.

From occultism to painting

Ociepka believed in his mission. At first, he focused on Janów and its vicinity. In practice what it meant was that on Sundays – when many locals went for a walk to a woodland park filled with kiosks selling sausages and beer – Teofil stood on a chair brought from home and gave speeches. After a while, a group of pupils gathered around him, 10 people at most. Ociepka lent them books from his extensive library: Max Heindel’s The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, Ernst Waldschmidt’s Die Überlieferung vom Lebensende des Buddha, Alma Frey’s volume of Édouard Schuré’s The Great Initiates. One of his pupils at the time was Ociepka’s later adversary, also a painter and a member of the so-called Janów Group, Bolesław Skulik.

Ociepka was also a correspondent member of the Rosicrucian Lodge established by Max Heidel in Oceanside in California. He was in regular contact with the Julian Ochorowicz Parapsychology Society in Lwów. He was a regular subscriber to the journal Lotos. Synteza wiedzy ezoterycznej [Lotus: Synthesis of Esoteric Science] published in Wisła and edited by Jan K. Hadyna. And, perhaps most interestingly for art lovers, he was in touch with Xawery Dunikowski, who supposedly introduced him to the Kraków Masonic Lodge in the 1930s.

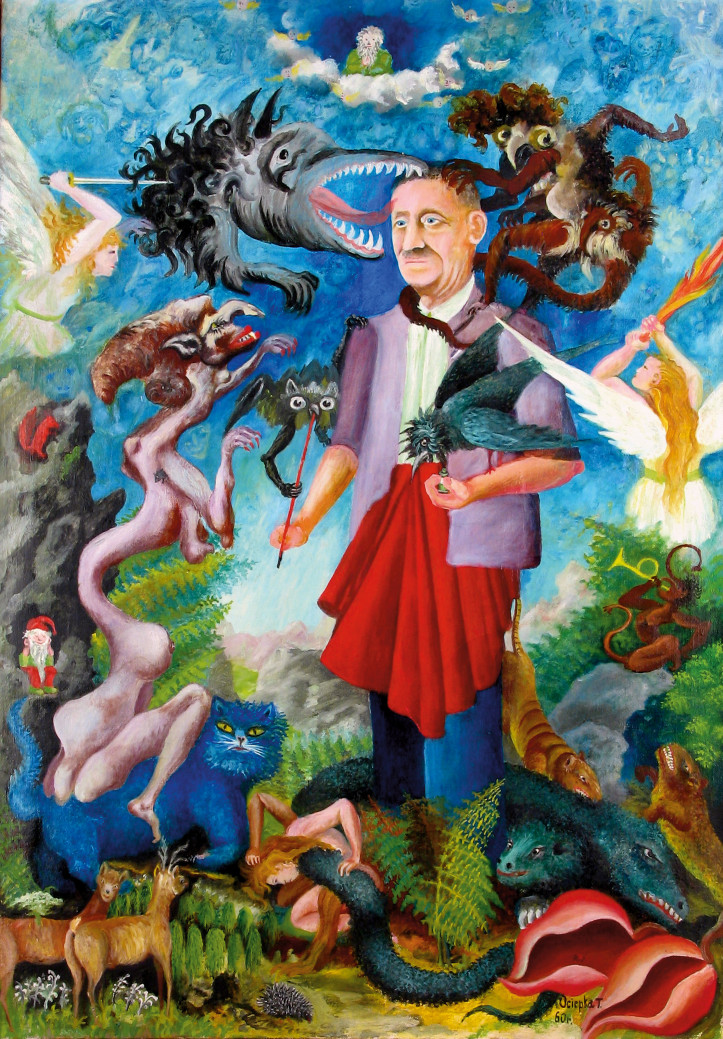

One of the roads leading to spiritual perfection in the Rosicrucian system is developing the sense of beauty, as “that in itself is a Divine element.” Four years after meeting Hohmann in person, whom Ociepka visited in Wittenberg, the master sent him a letter in which he promised: “I will send a spirit to you that will teach you how to paint.” Teofil was awaiting a meeting with a creature from an immaterial world and when that didn’t happen, another letter arrived: “Now the spirit will leave and you must paint on your own.” All of a sudden, in 1927, when he was 35 years old, Teofil Ociepka started painting with great eagerness. Between 1927 and 1930 he produced a series of large morality paintings, which, however, did not find appreciation in the eyes of the staff of the Silesia Museum in Katowice, which was just being created. Disappointed, Ociepka only returned to painting after the end of World War II.

Meanwhile, his spiritual master Philip Hohmann ended up in a Nazi concentration camp for promoting pacifism. He came back with a hole in his abdomen near his belly button. His Polish followers saw that as a sign of him obtaining the ‘philosophers’ stone’. Hohmann died in the 1960s, at the age of 64. Bolesław Skulik, who was mistrustful of him and thought him a fraud preying on Ociepka, commented on his death as follows: “He was promising the others, he was saying that he had the wisemen’s stone that the alchemists believed could be made, so if he had it and could live for two thousand years in health, here, in the material world, then why is he dead? Wasn’t he a fraud?”

The Janów Group

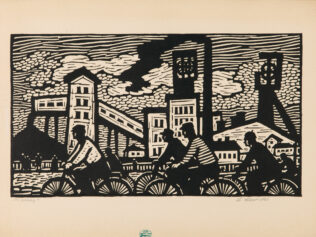

In 1946, the Voivodeship Cultural Board in Katowice organized an extensive exhibition of works by amateur painters from Upper Silesia. It was set up in response to the directives that came from the higher echelons of powers, defined as follows by the then propaganda and mass communication general Lesław Wojtasik: “By way of choosing, or rather selecting, each micro region had to designate one or several amateur artists and place them in positions of local leaders of propaganda creativity. The arrangement of the whole thing was to guarantee the outcome of activity of those promoted ideologically as spontaneous – their own – proving their sophistication and high class awareness. A sub-rule to this rule: it was best if those people were not party members, which increased their credibility in the eyes of people around them and, more widely – of local circles.”

The party directive landed on fertile ground. Many painters came forward, including Teofil Ociepka, who showed his previously mentioned morality paintings from the years 1927–1930. As a result, that same year a painters’ group called the Janów Group was created by the ‘Wieczorek’ mine Miners Trade Union. Members of the group included the aforementioned Bolesław Skulik, Paweł Stolorz, Gerard Urbanek, Leopold Wróbel, Eugeniusz Bąk, Paweł Wróbel and Ewald Gawlik. These are a handful of some of the famous ones. Later on, they were also joined by Skulik’s pupil, Erwin Sówka, who is still active today. Teofil Ociepka was, naturally, made the leader of the group.

At this point, as extra-curricular activities, I recommend two films. The first one is Lech Majewski’s and Adam Sikora’s Angelus, which tells the story of the Janów Group in a beautiful, though far from documentary way. The other one is Kazimierz Kutz’s The Beads on One Rosary, portraying the life of the Giszowiec settlement in the 1970s, to which Ewald Gawlik had strong links. Contrary to the script of Angelus, at least until 1956 the Janów Group painters were not allowed to paint what they wanted. Another member of the group, a one-armed janitor from the local community centre named Antoni Jaromin, recalled: “At that time, the themes were imposed. I disliked it strongly. I’m an amateur and I want to paint what I like and feel. It all depends on the day, the weather. But before they would tell you, ‘Paint the mine! Paint the secretary! Paint this one or another!’ Some other time they told us to paint Stalins as decorations in the mine, or some other things. How would an amateur cope? So we ended up with real caricatures, cripples, and people laughed their heads off.”

Under Bella’s eye

However Teofil Ociepka was already beyond the reach of party directives. He quickly become a Silesian icon – a “seventh day painter”, a “naive painter-miner”. He owed this exceptional position to just one person, and not a person from occultist circles. Her name was Izabela “Czajka” Stachowicz.

Bella, as she was known locally, was born in Sosnowiec in 1893. Her father, Wilhelm Szwarc, was a wealthy entrepreneur, raising his daughter on his own after they were left by the girl’s mother, Felicja, of French roots. Bella studied art history and Polish language and literature. After the war, she graduated with a doctorate in philosophy. She was a regular at the most fashionable cafés in Warsaw – including Adria, designed by her husband – as well as the cult Ziemiańska café, where she befriended, among others, Broniewski, Watt, Iwaszkiewicz, Gałczyński, Tuwim, Gombrowicz and Uniłowski. The last one portrayed her as Miss Leopard in his story Wspólny pokój [A Shared Room] (1925). Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz himself also commemorated Bella in his novel Pożegnanie jesieni [Farewell to Autumn] (1925) as the demonic heiress Hela Bertz.

After the war she started writing, mainly books, but also innumerable articles for “Przekrój”. She was most likely the only person who was able to correctly assess the phenomenon of Teofil Ociepka’s painting during the Katowice exhibition in 1946. She decided to promote him as a Polish version of Rousseau. In 1948, she organized his solo exhibition in Warsaw and introduced him to the Warsaw salons. He met his great admirers there: Julian Tuwim, Jan Kott and Artur Maria Swinarski. At the same time, Bella stretched a protective umbrella over Ociepka, which shielded him from attacks from party doctrinarians and the meanness of local officials in Silesia.

Thanks to her contacts, Ociepka was also introduced to prestigious galleries in Western Europe. He exhibited in Vienna, Paris, London and Amsterdam. In Warsaw, he showed his works again, this time in 1958 at the Zachęta gallery, as part of a collective exhibition with Nikifor, Paweł Stolorz, Paweł Wróbel and Leon Kudła. And then one more time in 1965, at Aleksander Jackowski’s exhibition entitled Different: From Nikifor to Głowacka.

Spirit and body

Occultists think that the planet of Saturn has a tremendous influence on what goes on here on Earth. Teofil Ociepka shared this conviction, which is why so many fantastic creatures appear in his paintings, derived in the smallest details from descriptions in one of the books he owned, Jakob Lorber’s Der Saturn [Saturn]. According to this book a human being, just like the universe, consists of a physical body, an astral body and a spirit. The human soul belongs to the astral world, to which it returns upon death. Saturn is peopled with astral beings that are at the same level of development as the soul, but imperfect. Those beings can come into contact with humans and can have a strong influence on them, often disastrous. The creatures in Ociepka’s paintings are therefore not just the creation of his imagination – in fact, the artist thought they really existed. He said that if humans were ever to reach Saturn, they would surely find them there.

The crucial element of occultist practices is achieving the state of mystical unity with God that is called the ‘philosophers’ stone’. This state can only be achieved by men, and only by those younger than 60. This is to do with the biological strength of the body required to undergo spiritual transmutation. An adept willing to achieve this must live in strict sexual ascesis. Ociepka did live in self-discipline, but when he turned 67, he realized that no hole would open in his belly button; that he would not achieve the philosophers’ stone. So he decided to get married. His chosen spouse was Julia Ufnal from Bydgoszcz. She knew Teofil from the press, and used to write nice letters to him in which she told him about her prophetic dreams regarding their future relationship and shared life. They got married in April 1958 and settled in Janów.

Teofil left the Janów Group and started painting more on more on commission. Mr and Mrs Ociepka travelled a lot, for example to Austria and Switzerland, where Teofil’s works were selling well. Eventually, in 1969, as a result of a bad aura surrounding them (or perhaps for some other reasons), they decided to move to Bydgoszcz. There, Teofil found himself in the tender care of Julia’s daughter, Irusia, and her husband, Ale, who was also his driver and legal adviser. Aleksander Jackowski, recollecting his last visit to the Ociepkas’ household, wrote: “Julia every now and then whispered whether they should take dollars or better ask for a Volkswagen, since money was so uncertain.” And then: “[…] the transaction fell through. There was no film either, because Julia asked for 600 złotys for each painting shown in it.”

Only in the above context can we say that Teofil Ociepka was a naïve painter. He left this world on 15th January 1978.

Translated from the Polish by Anna Błasiak