As a Belarusian who grew up in the Byelorussian SSR (BSSR), I remember how I first got to know about the Chernobyl tragedy.

I was on the streets in our communal yard riding my bicycle. My mother opened the window and called me home. I asked what had happened, but she loudly repeated: “Just come home!” At the flat, she explained to me that something was wrong with the weather. The following day, she asked me to eat a piece of black bread with two drops of iodine on it. She was a medic, and somehow knew about the possible thyroid problems that could arise as a result of radiation exposure. What she didn’t know – something that no nuclear energy specialist in Soviet Minsk ever explained publicly – was that liquid iodine bought from the pharmacy is not effective against radiation exposure. That’s why it was no surprise that across five years of standard medical inspection at my school, the doctor diagnosed in me an enlarging thyroid and ordered me to have a check-up every year. By the age of 21, I had lost my first schoolmate who was with me on that same communal yard during April 1986.

Fast-forward to June 2019, and a new miniseries has debuted on HBO, becoming the ‘highest-rated television show in history’ almost overnight. Chernobyl, as most of you will know by now, is an English-language dramatization of the reality that me, my friends, and many Soviet citizens of both the Byelorussian and Ukrainian SSRs lived through, not only in April 1986, but through decades of the consequences of radiation exposure. Admirably, Chernobyl attempts to explore the systemic failures that led to the tragedy in Pripyat, as well as telling the stories of the men and women who immediately assisted with the rescue and cleanup efforts.

Despite its well-researched and emotive storytelling, Chernobyl is let down by one understandable yet crucial misgiving: its English script fails to effectively grapple with the nuances of Soviet language use. Across many scenes in the miniseries, what appears completely normal in a Western paradigm sounds freaky to those who lived in the world of the USSR. In fact, the Iron Curtain’s least penetrable barrier might have been the one inside people’s heads; the inability to live one’s life outside of a specific narrative.

Chernobyl struggles to grasp with this reality, an apparent result of it being created, written and directed by Westerners trying to capture the discursive logic of a system of enslavement that they were never part of. This is why the show is so powerful when using documentary evidence (such as the real text announced by Soviet newscasters about the Chernobyl tragedy), yet sounds false when narrating fictional conversations between ‘ordinary people’.

Don’t blab!

Discursive practices in Chernobyl operate on two levels: that of everyday conversations (e.g. between soldiers, firemen and miners) and that of official Party plenums and meetings. The latter has already been analysed well, notably by Masha Gessen in The New Yorker. However, official language is not the weakest point of Chernobyl, since official meetings were recorded and documented, providing Craig Mazin (the screenwriter of the miniseries) with sufficient material to realistically represent the type of discussions that were held in the Kremlin. The real issue is within the linguistic patterns of ‘normal people’. The only sign of authenticity here is the ubiquitous use of the funny (and stereotypically unoriginal) word ‘comrade’. Let’s take a seemingly minor scene as the starting point for a discussion about everyday linguistic discrepancies in HBO’s Chernobyl.

It’s 26th April. The dead of the night. Soviet Ukraine. Two women are talking about a ‘fire’ at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. One of the ladies is the wife of a fireman sent to deal with the emergent problem. Both women act disturbed and stressed – just like how people in Independence Day act disturbed and stressed when they see flying saucers in the sky. The women speak:

“Is Vasily…?”

“Yeah.”

“Did he say it was bad?”

“No. No, he said it was just the roof. Well, he’s never gotten hurt before. None of the boys have.’

“He’ll be fine. Get some rest.”

The women are dressed authentically; one of them has a haircut just like Sarah Connor from the Terminator franchise. The fact that The Terminator was shot in 1984 makes this scene seem trustworthy enough.

That is, if you watch it on mute.

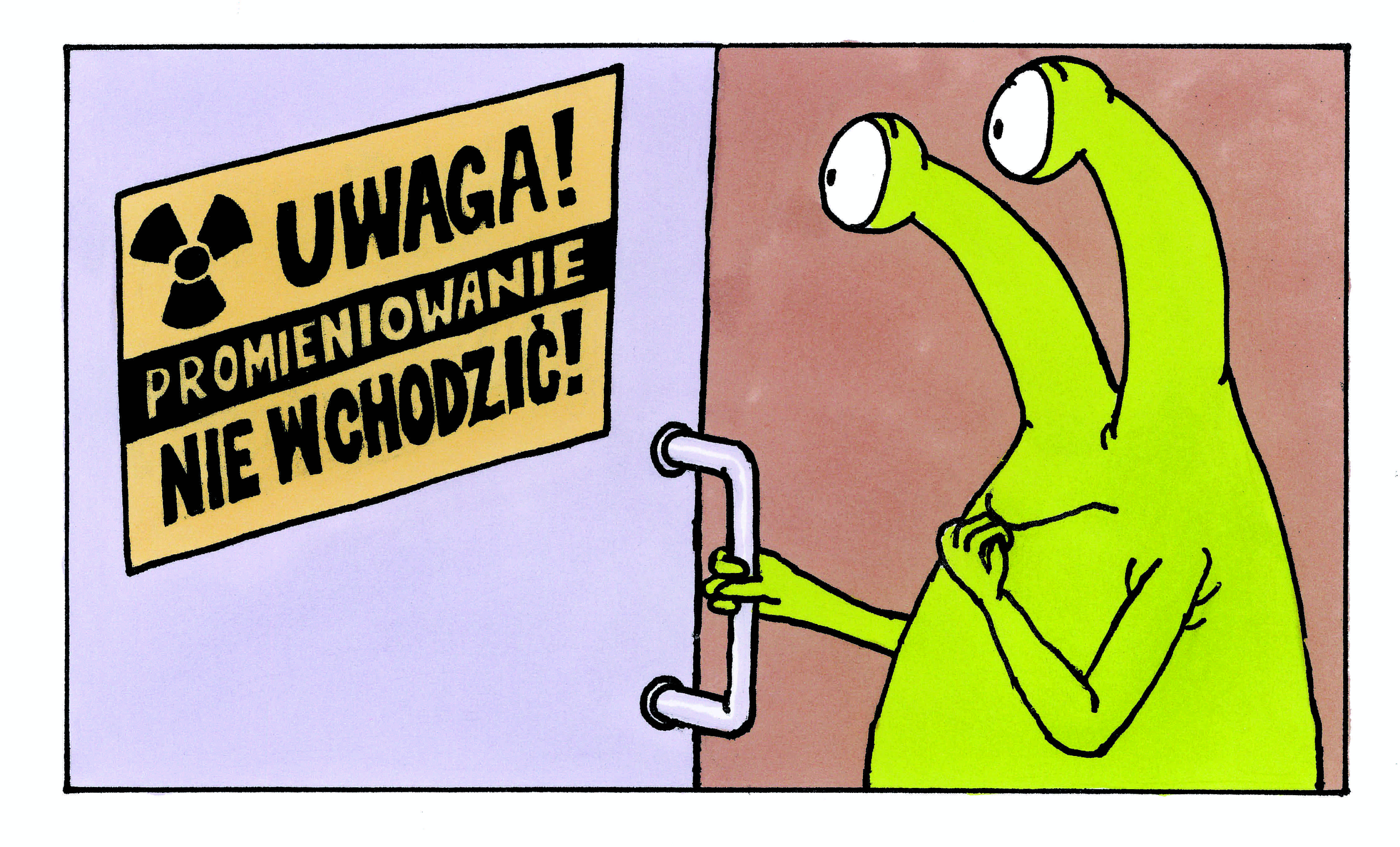

You see, there’s a problem with what the women say; the way in which they express their emotions. It’s all constructed through a Western prism. No Soviet fireman’s wife would have ever given anyone else details about the mission her husband was on. Nor would a Soviet fireman have been instructed via telephone about the exact details of a serious emergency. He would have simply been summoned, with no chance to get prepared for the mission or mention a word to his relatives. No Soviet fireman’s wife would have discussed her husband’s previous experiences. Not even with the neighbours. Especially not with the neighbours, in the year 1986, in the country with the infamous ‘Don’t blab!’ slogan.

And, of course, you have to be a complete alien in the Soviet galaxy to finish with the line: “He’ll be fine. Get some rest.” Soviet people didn’t make assumptions about each other’s emotions, as implied by ‘he’ll be fine’. Interestingly, this sort of linguistic subtlety becomes much more apparent when you watch Chernobyl in what was the official language of the USSR – that is, with Russian subtitles or dubbing. I did exactly this after painfully enduring most of Episode 1, leading to the revelation that the woman in the above scene says: Все будет хорошо (“Everything will be all right.”). She is not predicting someone’s future, because the very structure of Russian would make it inappropriate. Instead, she fatalistically expresses hope that everything will go well.

Similarly, two people on equal footing in the Soviet labour hierarchy would not close a conversation with ‘get some rest’. More realistically, this phrase might be uttered by your boss at the factory – not as a polite wish, but as a manifestation of the power that Soviet linguistic practices were impregnated with. Every phrase in everyday conversation was charged with power. If you told your neighbour to ‘get some rest’, you would likely offend them by acting like their boss.

The right to say ‘fuck’

Let’s return to another moment from Episode 1, when a fireman picks up a fragment of the power plant reactor’s core. He asks his colleague: “Vasily. Hey, Vasily, what’s this?” Vasily responds: “I don’t know Misha.” You could be forgiven for thinking that this was a conservation between two employees in an American supermarket, recognizing a new product on the shelf. Soviet firemen, on the other hand, would actually sound like this:

“Vasia! What the fuck is this shit”? “I dunno, Misha. I don’t give a fuck! Ask Sarge! Or better still, throw it the fuck outta here. Don’t you fucking touch it!”

Soviet people were never robots (even when they were sent to solve the problems that robots would fail to solve because of high radiation). Soviet people knew what they should never talk or joke about. Thus, outside of these borders, their language use was much more informal than that shown in Chernobyl. The right to say ‘fuck’ [or, more accurately, Блядь! (‘bliad’), a word literally meaning ‘whore’, but used by Russian speakers in a similar way to the English interjection ‘fuck’ – author’s note] was perhaps the only right people living in the USSR had. They embraced it with open arms.

Their thinking wasn’t particularly responsible, nor was it reflexive. Responsibility is learnt from freedom, where you have to think about consequences. Everyone in Soviet society was childish – from the elderly to teenagers, Party members to regular, unimportant workers. Soviet paternalism made them think like children, talk like children (who are only allowed to swear when ‘elders’ are not around) and act like children. That’s why the language of Eric Cartman from South Park would be much more accurate in Chernobyl than the formal language used by people in the Control Room when they see the first signs of big trouble.

Where is the fear?

There is one important character missing from Chernobyl. This character was perhaps the main hero of the story, but is hardly conceivable for someone who grew up in a world of Marvel and DC comics. This character’s name? Fear. Fear was present at every level of the Soviet system. Ordinary people were afraid of the KGB, of the militia, of the Party, of losing their job. The KGB was afraid of the militia; the militia was afraid of the KGB. High-ranking Party officials were afraid of being watched or heard by the KGB. Members of the Central Committee were devastated by their fear of the West: the system was paralyzed by the grip of the Cold War; the fear that they were losing and that capitalism would turn out to be far more productive than their version of socialism.

And, of course, fear manifested itself in language. It was present in both what you did say, and what you would never dare to say. It was noticeable in the differences between private and public language practices. The Soviet language – just like other languages – programmed the way in which people thought and behaved. This, in turn, constructed a language built on fear – everything that you did in the USSR had be to compatible with the KGB, the Party, socialism, Lenin, and so on.

In place of fear, Chernobyl invents the character of Ulana Khomyuk, who bravely fights against the system, traveling between Minsk, Pripyat and Moscow. This fearless, fictional creation thus has more in common with Superman or Batman than any historic Soviet person. These sorts of people were simply unable to exist in the USSR. Had Khomyuk existed, the Chernobyl disaster would have never happened. In the Soviet system, science and expert knowledge (as represented by Khomyuk, a nuclear physicist at the Belarusian Institute for Nuclear Energy) were not about making things safer. Scientists, professors and all other experts were not there to fight catastrophes or prevent tragedies; they were there to make things stable. They existed alongside the same KGB, militia and Party that Khomyuk fights against in Chernobyl. Indeed, if you were inside the system and tried to make things safer (just as the real-life Andrei Sakharov did), you immediately found yourself not the scientist, but the dissident.

Between East, West and Ancient Greece

Russian was the language of Soviet totalitarianism. The way that people were sentenced and killed during the Great Terror – the very narrative that surrounded the repressions – has never been mirrored in the English-language world. In the USSR, power was a direct product of language, and language was the only tool that could convince someone to talk about themselves as lacking freedom. The writer of Chernobyl has, understandably, failed to catch the narrative structures that programmed Soviet people – their reality was not only a matter of official documents or chronology. A person born to freedom could never imagine the motives of somebody who was born in fear and slavery. Such a screenwriter can make actors repeat what was said or done, but they will never understand why it was said or done like that.

It seems clear that an English-language dramatization of a Soviet tragedy might be the most efficient way to tell the Anglophone world one of the late 20th century’s most striking stories. Yet the system that provoked the Chernobyl disaster ended only 25 years ago, and many people born in the USSR are still alive. A lot of books have been written about the USSR (including the excellent Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More by Alexei Yurchak). However, in Chernobyl, it seems possible to accurately represent only the aesthetics of the USSR; its clothes, wallpaper and haircuts. While this has undoubted stylistic appeal, the intersection of language, freedom and power cannot and should not be underplayed.

In spite of its linguistic weaknesses, I still believe that Chernobyl is an important and worthwhile television series. Its creator’s intention was surely to describe, for viewers from a different epoch and different part of the world, what totalitarianism is, and it mostly does this well. Similarly, it outlines exactly what the consequence is of nuclear energy combined with an absence of freedom. Mikhail Gorbachev once suggested that Chernobyl may have contributed to the collapse of the USSR, and I would agree with him. The disaster at Chernobyl put extreme moral pressure on the leaders of the political system that enabled it. It was a tipping point for the limits of restricting freedom.

The absence or presence of freedom tends to be the most important component in understanding someone’s deeds. Western societies have developed alongside a tradition of freedom, which we can probably trace back to Ancient Greece. This may go some way to explaining the difficulties of comprehending a system of Soviet totalitarianism far detached from the experiences of an American production team. Thankfully, the Soviet system is now gone, along with the enslaving language and logic that accompanied it. As the former Eastern Bloc continues to integrate with democratic ideals, I am grateful that my grandchildren might live in a world shaped by Plato and Aristotle, rather than one of Party plenums and ‘Don’t blab!’ posters.